Alzheimer’s Disease in a Semi-Professional Pianist: A Case Study: Difference between revisions

(added categories) |

(added categories) |

||

| Line 226: | Line 226: | ||

[[Category:Queen's University Neuromotor Function Project]] | [[Category:Queen's University Neuromotor Function Project]] | ||

[[Category:Manual Muscle Testing]] | [[Category:Manual Muscle Testing]] | ||

[[Category:Balance]] | |||

[[Category:Dementia]] | |||

Revision as of 21:46, 13 May 2020

Alzheimer’s Disease in a Semi-Professional Pianist: A Case Study[edit | edit source]

By Sarah Arbour, Larissa Carlucci, Paola Finizio, Jamie Gray, and Alex Jones

ABSTRACT[edit | edit source]

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a common form of dementia which consists of loss of memory loss and other cognitive ability. The following is a fictional case study about a patient named Mrs. G. The purpose of the case study is to explore the clinical presentation and physiotherapy treatment of a semi-professional pianist with AD. Mrs G. is an 87 year old female who presents with a two-year history of AD. Recently, there nursing staff at Mrs. G’s retirement home recognized impairments in her cognition and consulted a physiotherapist. Following Mrs. G’s assessment, noticeable deficits in balance, cognition and fine motor control were discovered. The primary aim of Mrs. G’s treatment plan was focusing on improving fine motor skills in order for Mrs. G to be able to regain the ability to play the piano. The treatment plan also included balance, gait, endurance, strength and flexibility training. Following the intervention Mrs. G improved on her wrist extensor strength, strength, Timed up and Go ( TUG) score, Berg Balance Scale (BBS), Action Research Arm Test (ARAT). The intervention ultimately decreased her risk of falls by enhancing her balance and increased her wrist extensor strength to assist her in playing the piano. Mrs. G should continue to attend physiotherapy monthly to monitor her condition and progress her exercises. The physiotherapist’s role in patients with AD is to address any body structure and function impairments as well as assisting the patient to overcome their activity and participation restrictions. Further, a physiotherapists role has been found to help prevent the progression of physical and cognitive decline.[1]

Abbreviations:

- AD = Alzheimer’s Disease

- ADL = activities of daily living

- ARAT = Action Research Arm Test

- AROM = active range of motion

- BBS = Berg Balance Scale

- b/l = bilateral

- CoG = centre of gravity

- CVD = cardiovascular disease

- FAQ = Functional Activities Questionnaire

- IADL = instrumental activities of daily living

- L = left

- L/E = lower extremity

- MMSE = Mini-Mental State Exam

- MMT = manual muscle test

- R = right

- TUG = Timed Up and Go Test

- U/E = upper extremity

- WHOQOL-BREF = World Health Organization Quality of Life-BREF

- WNL = within normal limits

INTRODUCTION[edit | edit source]

This article details a fictional case developed by physiotherapy students for educational purposes.

Alzheimer’s Disease, by definition, is a progressive neurodegenerative disease affecting memory and cognition[2]. Common in older adults, Alzheimer’s Disease is the most prevalent pathophysiology causing approximately 60-80% of dementia cases[3]. Some key risk factors include age >65 years, hypertension, obesity, family history and other genetic factors[4].

The following video provides an overview of dementia and recommended strategies for supporting individuals with dementia.

The deterioration of neurological function is due to brain cell death, primarily caused by plaques that block nerve signals and tangled proteins that prevent nutrient circulation in neurons[2]. Clinical presentation of the disease has substantial variance between patients, depending on the location of brain inflammation and atrophy. Common signs and symptoms of Alzheimer’s Disease include impairments in memory, problem solving, reasoning, comprehension, attention, and orientation[5].

Several researchers have explored the role of physiotherapy in the management of Alzheimer’s Disease, on a case-by-case basis. One such example is a fictional case study describing the benefits of physiotherapy education and home exercise programs to manage aerobic fitness and strength in a patient with Early-Onset Alzheimer’s. In another case study, researchers collected qualitative data through interviewing two patients and their spouses to investigate the relationship between participation in physical activity and Alzheimer’s Disease[6]. Furthermore, a systematic review was conducted to address the barriers, facilitators and motivators for physical activity participation in individuals with Alzheimer’s Disease. This study identified the importance of caregiver involvement and individualized exercise programs to promote physical activity participation in this population[7].

In patients with Alzheimer’s Disease, physiotherapy has been shown to preserve independence through mobility exercises and functional task training[8]. Physiotherapy has also been shown to prevent falls through strengthening, stability, postural control and balance training[9][10]. Moreover, physiotherapy can help to control behaviour and mood through pain management and regular exercise[11]. Additionally, physiotherapy may have a protective effect on cognitive function and could contribute to delaying decline in neurological function[12].

Despite the benefits of physiotherapy mentioned above, patients with Alzheimer’s Disease are at a higher risk for longer hospital stays, lack of access to healthcare services, premature institutionalization, and inadequate care that does not meet their goals[10][13]. This highlights the importance of rehabilitation interventions that aim to prolong function and preserve independence in this patient population.

The purpose of this fictional case study is to explore the role of physiotherapy in maintaining functional independence and delaying decline in neurological function for a patient with Alzheimer’s disease. Specifically, this patient presents with several cognitive deficits, including short-term memory loss and behavioural changes, as well as motor impairments in fine motor control, balance and coordination. The following sections explore various assessment techniques and intervention strategies aimed to enhance participation and optimize quality of life for individuals with Alzheimer’s Disease.

CLIENT CHARACTERISTICS[edit | edit source]

Mrs. G is an 87-year-old female who presents with a two-year history of Alzheimer's Disease. She is relatively healthy and active, despite comorbid conditions including hypertension and osteoporosis. Mrs. G is a retired English teacher of 41 years and semi-professional piano player who started playing early in her childhood. Following her diagnosis, Mrs. G’s family decided to move her into a retirement home to ensure that she was well-supported with access to nursing and personal support staff. Over the last month, the nursing staff at her retirement home noticed a significant decline in her cognitive function involving short-term memory deficits, confusion, paranoia, and recurrent irritability. However, her long term memory has not yet become an issue. In response to these findings, they consulted a physiotherapist to address Mrs. G’s concerns. During the physiotherapy assessment, Mrs. G notes that she is experiencing difficulty playing the piano. She reports feeling as though her hands were not able to move like they used to, making it challenging to play intricate songs. She is particularly troubled by the deficits in her upper extremity fine motor skills, as one of her favourite activities is playing the piano every evening. Mrs. G also communicates that she is experiencing a loss of balance when walking around the retirement home, making it more difficult to participate in daily walks and fitness classes.

EXAMINATION FINDINGS[edit | edit source]

SUBJECTIVE[edit | edit source]

Patient Profile: 87-year-old female

History of Present Illness: Mrs. G was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s Disease two years ago. Over the past month, she has presented with fine motor, balance and coordination deficits disrupting her piano playing and daily physical activity. As noted by the nursing staff, she is showing signs of short-term memory loss and paranoia.

Past Medical History: Previous bilateral knee surgery for meniscal repair six years ago

Medications: Bisoprolol, Aricept, Memantine

Health Habits: Previous smoker (8 pack years) who currently does not drink any alcohol

Family History: Mother passed away at age 98 from Alzheimer’s Disease. History of cardiovascular disease on the paternal side.

Social History: Mrs. G is a retired English teacher. She currently lives alone in a retirement home apartment with some assistance in ADLs. She has two daughters who live within two hours of the retirement home and visit most weekends. Mrs. G spends her days playing the piano and loves to interact with the other residents. She takes daily walks around the gardens with friends, and attends weekly fitness classes at the residence.

Previous Functional History: Independently ambulatory without a gait aid for 30 meters with minimal fatigue. Able to play piano for 30 minutes every day without coordination difficulties.

Precautions/Contraindications: Short-term memory loss and paranoia may interfere with learning new exercises and adherence to the treatment plan.

OBJECTIVE[edit | edit source]

Observation:

- Forward stooped posture

- Thoracic kyphosis

- No use of gait aid

Gait Analysis:

- Slowness of movement showing signs of bradykinesia

- Able to walk 10 meters before losing balance

- Wide base of support and notable instability

- Shortened gait cycle

- Significant loss of concentration and attention

- Forward stooped posture to adjust CoG

ROM:

- Cervical AROM: L and R rotation ½ range

- Shoulder AROM: WNL

- Wrist AROM:

- R wrist flexion full ROM

- R wrist extension ¾ range, limited by muscle weakness

- L wrist flexion full ROM

- L wrist extension full ROM

Manual Muscle Tests:

- U/E:

- Shoulder: 5/5 strength for all movements b/l

- Elbow: 5/5 strength for all movements b/l

- Wrist: moderate weakness, pain-free, and poor motor control b/l. R wrist extensor strength grade 3/5.

- L/E: 3/5 mild weakness, pain free, and slight motor control deficits b/l

Outcome Measures:

- Mini-Mental State Exam: Score of 18

- Testing for dementia

- Mini-Cog: score of 2/5 (clinically meaningful cognitive impairment)[14]

- Involves clock drawing

- Timed Up and Go Test: score of 14 seconds

- Slow speed is a sign of the disease

- Berg Balance Scale: score of 40

Fine Motor Control Tests:

- Action Research Arm Test: score of 25 (predicted moderate recovery)

- Testing for upper extremity performance 16 of 19 reflect fine movement of hands or fingers[15]

Coordination Tests:

- Finger to nose: smooth, coordinated with slight dysmetria R>L[16]

- Finger opposition: moderate impairment R>L with lack of coordination

Self-Reported Outcome Measures:

- WHOQOL-BREF: scores of 66/100 (physical), 84/100 (psychological), 72/100 (social relationship), and 81/100 (environment)[17]

- Functional Activities Questionnaire: score of 12

CLINICAL HYPOTHESIS[edit | edit source]

Clinical impression:

During the subjective interview, it was noticed that she is having difficulty with fine motor control, balance, and coordination. This is affecting her ability to perform IADL’s such as brushing her teeth and getting dressed. The patient is becoming more fatigued when playing the piano with noticeable deficits in coordination and muscle strength. She has noticeable short-term memory deficits and shows signs of paranoia.

The patient’s TUG score of 14 seconds indicates she is at a high risk of falls and is dependent in the community. Further her BBS score of 40/56 supports the balance problems she is experiencing and also places her at a medium risk of falls. Mrs G. received a score of 45 on the The Action Reach Arm Test, indicating moderate recovery with respects to her U/E performance. She scored lowest on the 16 items reflecting fine movement of the hand and fingers. Her performance on the finger to nose, and finger opposition showed decreased fine motor coordination revealing mild dysmetria. Her FAQ score 12/30 revealed she is dependent and has impaired function and possible cognitive impairment, specifically with her IADLs. The patient’s cognitive ability was assessed using Mini-Mental State Exam and the Mini Cognitive Exam where both revealed a mild cognitive and clinically meaningful cognitive impairment. Furthermore, both tests support the classification of Mild Alzheimer's Disease. The weakness she is experiencing in her L/E can be a contributing factor to the loss of balance, whereas the weakness in her U/E can be attributed to her decreased ability to play the piano and complete fine motor tasks.

Problem list:

- Decreased ability to perform IADLs based on FAQ score

- Decreased fine motor control and coordination impacting her ability to play piano

- Decreased balance: instability and loss of balance within 10 meters during gait

- Trouble with certain ADLs including brushing teeth due to fine motor issues

- Cognitive impairment: components of Mini-Cog test, short-term memory loss, behavioural changes

INTERVENTION[edit | edit source]

Goals:

Improve TUG score to 10 seconds within 10 weeks in order to be classified as independent and low risk of falls.

Return to playing one song on the piano for the nursing home 2x/week with minimal finger and hand muscle fatigue by 12 weeks.

Improve BERG score to 46/56 to decrease falls risk and increase ability to walk without loss of balance by 6 weeks.

Improve score of Action Research Arm test from 25 to 20 to recover fine motor loss by 6 weeks of treatment.

Maintain MMSE score of 18 to prevent decline in cognitive status through use of exercise training 3 times per week.

Treatment Plan:

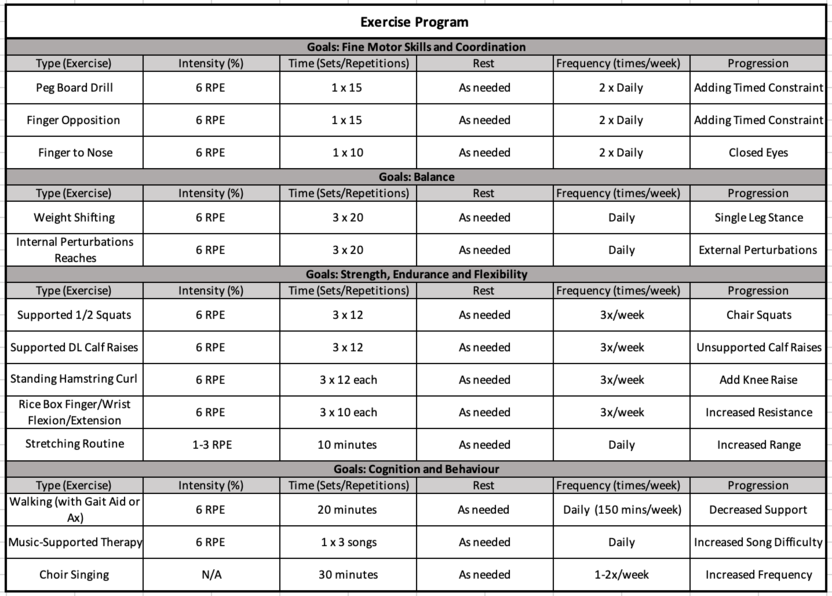

Considering the importance of playing the piano on Mrs. G's everyday life, the primary aim of the intervention was targeted at improving her fine motor skills. Secondary concerning issues discovered on examination included Mrs. G's balance and coordination deficits as well as her short term memory and behavioural changes. To target these issues, the treatment plan also included gait and balance training exercises as well as endurance, strength training and flexibility exercise[18]. A study completed in 2004 suggested that CardioFit, strength training and flexibility exercise have a moderate positive effect on cognitive tasks, functional tasks, and behaviour[18]. We also included a unique addition to the exercise program based on a study done by Sabine Schneider in 2010. This study showed that music-supported therapy, in which patients produce tones, scales, and simple melodies on an electronic piano or an electronic drum set, significantly enhanced cognitive functioning in the domains of verbal memory and focused attention. Music-supported therapy was also shown to improve depressive symptoms and mood, which are both common symptoms in patient's with AD[19]. We decided to include music-supported therapy in Mrs. G's treatment, as we felt it would be an additional tool to help return her to the IADLs she enjoys, particularly piano playing.

The following chart demonstrates the various exercises and what they are targeting:

OUTCOME[edit | edit source]

Following the assessment of Mrs. G a 3 month physiotherapy plan was implemented. Her treatment plan was directed towards improving her fine motor movements and coordination, balance during stationary standing and dynamically during gait, . The program consisted of 3 sessions per week focusing on strength and endurance. Mrs. G also performed the fine motor control activities and balance exercises daily. A follow up assessment was completed weekly for the first month and biweekly for months 2 and 3.

During the 3 months of treatment, Mrs. G’s U/E MMTs improved slightly. Notably, there was an improvement in Mrs. G’s R wrist extensor strength to a ⅘. Similarly, Mrs. G’s R wrist ROM improved to near full ROM. These improvements will assist Mrs. G with her piano playing.

The scores on her outcome measures are listed below

- MMSE = 18/30

- Mini clock drawing = 2/5

- TUG = 10 seconds

- BBS = 45/56

- ARAT = 35/57

- FAQ = 12

The MMSE and mini clock drawing tests stayed the same revealing there was no change in cognitive status for the patient. These tests will continually be used to track her cognitive state over time. The combination of strength, endurance, balance and coordination exercises resulted in a decrease in Mrs. G’s TUG score by 4 seconds placing her at a lower risk of falls. Mrs. G demonstrated a positive response to the balance intervention observed through her noticeable improvement on her BBS score. Mrs. G’s BBS score increased by 5 points with improvements in specific components of test including standing unsupported, standing with eyes closed and standing with feet together. The ARAT was used as both an assessment and treatment tool revealing an improvement of 10 points highlighted by the fine motor movement items (should we list some items here? Like pinch etc?).

Mrs. G should continue to attend Physiotherapy monthly in order to track her improvement, address any new concerns and progress her exercises. Her appointments will assist her with managing her coordination, balance and fine movement control during her piano playing and ambulation. Secondary impairments should be monitored since they may arise with the progression of the Alzheimer’s Disease. Mrs. G should also receive a referral to an occupational therapist to assess her apartment ensuring she is able to complete her ADLs. In future she should be reassessed for the potential need of an assisted device and safety regarding any decline in her mental status.

DISCUSSION[edit | edit source]

Overall summary of the case

- Demographic

- Chief complaint

- Clinical impression

- Treatment intervention

- Outcomes

- What we learned from Mrs. G

A unique finding in Mrs. G’s case is her difficulty controlling her hands despite her ability to remember all of her piano songs. The fine motor task of piano playing is stored as a motor program in the brain, while the memory component of music would be stored in a separate brain area. Thus, this discordance may be attributed to the area of Mrs. G’s brain affected by the disease pathology, with the cognitive aspect of the skill remaining intact while the motor aspect is impaired. In this case, outcome measures including the Action Research Arm Test, the finger-to-nose test and the finger opposition test were used to assess Mrs. G’s upper extremity fine motor control and coordination. By quantifying Mrs. G’s motor impairments using these objective assessment tools, the physiotherapist can create an individualized intervention plan targeting the areas in need of improvement.

In the literature, there are many case studies investigating the role of physiotherapy in treating older adults with Alzheimer’s Disease. Similar to Mrs. G, many patients with this disease experience cognitive symptoms such as short term memory loss and confusion, behaviour changes including aggression and paranoia, and motor deficits in balance, coordination, and fine motor skills[5]. There is strong evidence suggesting that physiotherapy is helpful in the management of Alzheimer’s Disease, through its contribution to preserving independence, preventing falls, and delaying cognitive decline[8][9][10][12].

Despite the known benefits of physiotherapy management, patients with Alzheimer’s disease and related neurological disorders have higher rates of health disparities associated with loss of independent living and autonomy in decisions regarding their healthcare plans[20]. Click the following link to learn more about some of the key health disparities related to the stigma surrounding the various forms of dementia: Alzheimer Society 2017 Awareness Survey.

Several factors may contribute to the health disparities experienced by individuals with Alzheimer’s Disease[21]. Some examples include:

- Lack of autonomy and involvement in care planning

- Lack of participation in exercise interventions

- Lack of social support, leading to poor mental health and problematic behaviours

- Lack of disease-specific education and training for healthcare providers

As integral members of the care team, physiotherapists can be important advocates for patients with Alzheimer’s Disease. Firstly, physiotherapists can implement patient-centered care by discussing patient-centered goals, considering the patient’s values and beliefs, and treating patients with dignity and respect. Secondly, physiotherapists can promote autonomy by informing patients of their rights, supporting patients in their decisions, and ensuring patients have adequate access to healthcare. Thirdly, physiotherapists can show compassion by taking the time to actively listen to the patient, build therapeutic rapport to enhance emotional comfort, and encourage patients to be active participants in their treatment plan.

The main goals of physiotherapy interventions in this population should include preserving independence and optimizing quality of life. The following outlines several ways in which this can be achieved.

- Enhance patient autonomy by providing choices whenever possible

- Emphasize functional task training to enhance independence in ADLs and IADLs and reduce caregiver burden

- Take the time to understand the patient’s individual needs to provide patient-specific resources

- Educate caregivers on services available in the community to prevent burnout

In addition to the suggestions outlined above, the following provides some general guidelines that physiotherapists can use when working with patients with Alzheimer’s Disease.

- Schedule a regular routine for treatments

- Ask simple, specific questions

- Focus on one task at a time

- Minimize distractions in the environment

- Maintain patient dignity at all times

- Introduce yourself and your role with every interaction

- Ask about symptoms frequently

- Talk to the patient rather than the caregiver whenever possible

Due to the nature of Alzheimer’s Disease, communication can be a challenge for physiotherapists. The following video provides suggestions for enhancing communication with individuals with dementia.

To put these strategies into practice, physiotherapists can enhance verbal communication by providing simple stepwise instructions and speaking slowly with frequent pauses to allow sufficient time for information processing[22]. Furthermore, non-verbal communication can be optimized by utilizing actions or images to explain tasks, while being mindful to use non-threatening body language[22]. Additionally, communication can be enhanced by engaging in active listening and demonstrating empathy[23].

To summarize, physiotherapy is an integral part of managing symptoms of Alzheimer’s Disease and can contribute to enhancing quality of life and preserving independence in this patient population. It is important for physiotherapists to collaborate with an interprofessional care team to provide personalized care that aligns with the patient’s goals[24]. There are numerous strategies that physiotherapists can use to promote open communication and provide effective patient care while considering implications of the disease. By providing patient-centered care, physiotherapists can help patients maintain their physical and cognitive functioning, allowing them to participate in meaningful activities within their community.

SELF-STUDY QUESTIONS[edit | edit source]

The following questions are intended for self-study purposes to test your knowledge obtained from reading this case study.

In your initial assessment, you are evaluating Mrs. G’s walking gait. You notice that after about 10 meters, she begins to lose her balance. Which compensation strategy might Mrs. G use to prevent herself from falling?

- Decrease step length to minimize time in single leg stance

- Increase walking speed to reduce postural sway

- Reduce base of support by keeping her feet closer together

- Increase hip flexion in the swing phase to maintain upright posture

On your fifth visit with Mrs. G, she does not recognize you seems reluctant to participate in physiotherapy. What would be an appropriate way to respond?

- Encourage Mrs. G to try to remember who you are by explaining what you did in the previous treatment session

- Leave Mrs. G alone because she is exhibiting unusual behaviour

- Ask the Mrs. G’s caregiver for consent to proceed with treatment, as Mrs. G is unable to make this decision for herself

- Re-introduce yourself, explain your role as a physiotherapist, and your goals for the treatment session

During a physiotherapy treatment session, you are teaching Mrs. G a new exercise and she seems to be confused by your instructions. What would be an appropriate strategy to facilitate teaching this skill?

- Provide multiple cues to allow her to make connections between the various aspects of the skill

- Demonstrate the exercise before she performs it and provide simple instructions one step at a time

- Explain the exercise in detail and describe the muscles being activated in each stage of the movement

- Describe the biomechanics of the exercise to help her better understand the movement pattern

REFERENCES[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Lord S, Rochester LY. Role of the physiotherapist in the management of dementia. 2017 Feb 24 (pp. 240-248). CRC Press.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Alzheimer Society Huron County, Alzheimer’s Disease. 2019. Available from: https://alzheimer.ca/en/huroncounty/About-dementia/Alzheimer-s-disease [Accessed 13th May 2020].

- ↑ Alzheimer's Association. 2019 Alzheimer's disease facts and figures. Alzheimer's & Dementia. 2019 Mar;15(3):321-87.

- ↑ Forsyth E, Ritzline PD. An overview of the etiology, diagnosis, and treatment of Alzheimer disease. Physical therapy. 1998 Dec 1;78(12):1325-31.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Kaur J, Garnawat D, Bhatia MS, Sachdev M. Rehabilitation in Alzheimer’s disease. Dehli Psychiatry J. 2013 Apr;16:166-70.

- ↑ Cedervall Y, Åberg AC. Physical activity and implications on well-being in mild Alzheimer's disease: A qualitative case study on two men with dementia and their spouses. Physiotherapy theory and practice. 2010 Jan 1;26(4):226-39.

- ↑ van Alphen HJ, Hortobagyi T, van Heuvelen MJ. Barriers, motivators, and facilitators of physical activity in dementia patients: A systematic review. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics. 2016 Sep 1;66:109-18.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Elkins M. Exercise slows functional decline in nursing home residents with Alzheimer's disease. Australian Journal of Physiotherapy. 2007 Sep 1;53(3):204-5.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Manckoundia P, Taroux M, Kubicki A, Mourey F. Impact of ambulatory physiotherapy on motor abilities of elderly subjects with A lzheimer's disease. Geriatrics & gerontology international. 2014 Jan;14(1):167-75.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Fernando E, Fraser M, Hendriksen J, Kim CH, Muir-Hunter SW. Risk factors associated with falls in older adults with dementia: a systematic review. Physiotherapy Canada. 2017;69(2):161-70.

- ↑ Williams CL, Tappen RM. Effect of exercise on mood in nursing home residents with Alzheimer's disease. American Journal of Alzheimer's Disease & Other Dementias®. 2007 Oct;22(5):389-97.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Barnes JN. Exercise, cognitive function, and aging. Advances in physiology education. 2015 Jun;39(2):55-62.

- ↑ Murray ME, Shee AW, West E, Morvell M, Theobald M, Versace V, Yates M. Impact of the Dementia Care in Hospitals Program on acute hospital staff satisfaction. BMC health services research. 2019 Dec 1;19(1):680.

- ↑ Borson S, Scanlan JM, Chen P, Ganguli M. The Mini‐Cog as a screen for dementia: validation in a population‐based sample. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2003 Oct;51(10):1451-4.

- ↑ Norman KE, Héroux ME. Measures of fine motor skills in people with tremor disorders: appraisal and interpretation. Frontiers in neurology. 2013 May 10;4:50.

- ↑ Iverson GL. Finger to nose test. Encyclopedia of Clinical Neuropsychology. New York: Springer. 2011:1051.

- ↑ Lucas-Carrasco R, Skevington SM, Gómez-Benito J, Rejas J, March J. Using the WHOQOL-BREF in persons with dementia: a validation study. Alzheimer Disease & Associated Disorders. 2011 Oct 1;25(4):345-51.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Heyn P, Abreu BC, Ottenbacher KJ. The effects of exercise training on elderly persons with cognitive impairment and dementia: a meta-analysis. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 2004 Oct 1;85(10):1694-704.

- ↑ Schneider S, Müünte T, Rodriguez-Fornells A, Sailer M, Altenmüüller E. Music-supported training is more efficient than functional motor training for recovery of fine motor skills in stroke patients. Music Perception: An Interdisciplinary Journal. 2010 Apr 1;27(4):271-80.

- ↑ Alzheimer Society Canada, Dementia Number in Canada. 2019. Available from: https://alzheimer.ca/en/Home/About-dementia/What-is-dementia/Dementia-numbers [Accessed 13th May 2020].

- ↑ Murray ME, Shee AW, West E, Morvell M, Theobald M, Versace V, Yates M. Impact of the Dementia Care in Hospitals Program on acute hospital staff satisfaction. BMC health services research. 2019 Dec 1;19(1):680.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Alzheimer's Australia. Dementia care in the acute hospital setting: issues and strategies. Canberra: Australia Alzheimer's Australia 2014. Report No.: 40.

- ↑ Hall AJ, Burrows L, Lang IA, Endacott R, Goodwin VA. Are physiotherapists employing person-centred care for people with dementia? An exploratory qualitative study examining the experiences of people with dementia and their carers. BMC geriatrics. 2018 Dec;18(1):63.

- ↑ Handley M, Bunn F, Goodman C. Dementia-friendly interventions to improve the care of people living with dementia admitted to hospitals: a realist review. BMJ open. 2017 Jul 1;7(7).