Hip Dysplasia

Original Editors - Daan Vandebriel, Ruben Van Laere

Top Contributors - Samuel Adedigba, Lucinda hampton, Kim Jackson, Lauren Heydenrych, Vidya Acharya, Laura Ritchie, Sai Kripa, Admin, Ruben Van Laere, WikiSysop, Ewa Jaraczewska, Oyemi Sillo, Rucha Gadgil and 127.0.0.1

Introduction[edit | edit source]

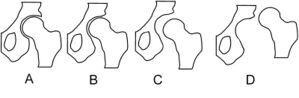

DDH (developmental dysplasia of the hip ) is a disorder that is due to abnormal development of acetabulum with or without hip dislocation. Early diagnosis and management will prevent long term complications eg persistent dislocation,limp and early hip osteoarthritis.[1]

Image 1: Schematic depiction of hip joint structures' positions in hip dysplasia A - Normal, B - Dysplasia, C - Subluxation, D - Luxation

Presentation varies from minor hip instability to frank dislocation. The exact etiology is still elusive. Multifactorial in nature, a combination of genetic, environmental, and mechanical factors plays a role.[1]

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

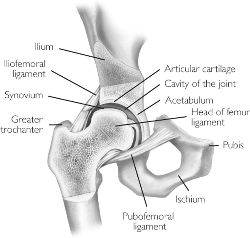

The Hip joint is a classical ball-and-socket joint. It meets the four characteristics of a synovial or diarthrodial joint: it has a joint cavity, joint surfaces are covered with articular cartilage, it has a synovial membrane producing synovial fluid, and it is surrounded by a ligamentous capsule.[2]

- Embryologically, the femoral head and acetabulum develop from the same block of mesenchymal cells. A cleft develops after 7 to 8 weeks and will separate the femoral head from the acetabulum. Postnatally, the acetabulum will develop and there will be a growth of the labrum which will deepen the socket.

- A deep concentric position of the femoral head in the acetabulum is necessary for a normal development of the hip. When the bone structures of the hip are fully grown, we can speak of a ball and socket joint between the rounded head of the femur and the cup-like acetabulum of the femur.[3]

Pathology[edit | edit source]

The formation of the hip joint is highly dependent on the dynamic relationship between femur and acetabulum. Any interference with proper contact between these two in utero or infancy leads to DDH.

Maligned contact for a prolonged period leads to chronic changes like hypertrophy of capsule, ligament teres, the formation of thickened acetabular edge (neolimbus), which further prevents the contact, and prevents the relocation of the femoral head[1]. The very cellular hyaline cartilage allows the femoral head to glide out of the acetabulum generating the palpable clunk known as the Ortolani sign.[4]

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

The reported incidence of developmental dysplasia of the hip varies between 1.5 and 20 per 1000 births, with the majority (60-80%) of abnormal hips resolving spontaneously within 2-8 weeks (so-called immature hip).

The incidence varies from 0.06 in Africans to 76.1 per 1000 in Native Americans due to the combination of genetics and swaddling.[4]

Etiology[edit | edit source]

The following are the risk factors for DDH:

- Female gender (M: F ratio ~1:8) The increased incidence is probably due to ligamentous laxity from maternal hormones.[1]

- Firstborn baby. The incidence of DDH is 10 times more in new borns with breech malposition

- Family history. eg Certain ethnic populations (Native Americans and Sami people). Some studies suggest it is linked with the hormone relaxine and /or it has something to do with chromosone 13

- Breech presentation. The legs of the foetus are pressed inside the uterus leading to hip dislocation if the ligaments are lax. The caput femoris tends to be pushed out of the acetabulum.

- Any physical limitation (eg oligohydramnios, twins) in utero can contribute to DDH. It also increases the risk of other abnormalities like Metatarsus adducts, congenital muscular torticollis, and congenital knee dislocation.

- Spina bifida[4]

- Swaddling in the adducted and extended position. Explains the increased incidence in specific populations including American Indians, Japanese and Turkish infants[1].

- Structural abnormalities eg shallow acetabulum, a flat or irregular caput femoris, a femoral or acetabular anteversion, and a decreased head offset or perpendicular distance from the center of the femoral head to the axis of the femoral shaft.[5][6][7]

Characteristics/ Clinical presentation[edit | edit source]

Clinical features vary for mild hip instability, limited abduction in the infant, less mobility or flexibility on one side, limping or toe walking, and osteoarthritis in the adult.[1]

Developmental dysplasia of the hip is usually suspected in the early neonatal period due to the widespread adoption of clinical examination (including the Ortolani test, Barlow manoeuvres, and Galeazzi sign).[4]

- Ortolani maneuver: Infant in the supine position, hip flexed at 90 degrees and in neutral rotation. The infant should be calm, and clothes and diapers should be removed. This manoeuver reduces dislocated hip. The hip is held in the way the thumb on the inner aspect and index and ring finger on the greater trochanter. While applying anterior force on the greater trochanter, gently abduct the hip. If the hip dislocated, one would feel a jerk or clunk. "Hip clicks" are clinically insignificant without instability.[11]

- Barlow maneuver: in the same above position, while applying posterior force to trochanter (AAP recommends against posterior force), adduct the hip. You will feel the clunk or jerk if the hip can be dislocated. This maneuver should be done gently as forceful adduction can cause instability[1]

Diagnostic procedures[edit | edit source]

It is important to examine DDH in an early stage. This is not easy because of the lack of a definitive test or finding on examination. The disorder is also painless so there are no symptoms in the infant. Particularly bilateral dislocations are difficult to detect. All newborns are to be screened by physical examination. This examination includes an Ortolani or Barlow test.

If these tests are negative but the provocation test is positive, an ultrasonography is recommended. In most cases, an ultrasonography will provide clarity about the disorder, but it is not recommended to carry out such a test for all newborn.[3][8][9] A ultrasound has proven to be more useful defining the anatomy until the cartilage is ossified.[10] Sometimes an MRI is also used. CT scans or 3D CT scans rarely are used. Sonographic examination is another diagnostic procedure.[11] Its main disadvantage is that it might lead to over diagnosis, which might cause over treatment.

Other signs of hip dysplasia are asymmetric gluteus folds and an apparent limb-length inequality.

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

There is a difference in treatment approach between the neonatal cases and the cases where the disorder is examined between 6 months and 6 years. In the case where the dislocation is found on neonatal screening a 3 week wait is observed before intervention. Sometimes the hip becomes stable spontaneously. In this case it is still important that the child is re-examined at the age of 5 or 6 months. If on the other hand the hip is still unstable after three weeks, splinting in the reduced position in moderate abduction is recommended for a minimum of six weeks or for as long as instability persists. When splinting is needed for a longer period, the risk for the development of avascular necrosis of the femoral head will increase.

Between six months and six years there are three essential principles of treatment. First of all to secure the concentric reduction, secondly to provide conditions favorable to continued stability and normal development and thirdly to observe the hips regularly in order to detect any failure of normal development of the acetabulum and to apply appropriate treatment when necessary.

If possible, it is important to obtain reduction by non-operative means. Surgery is performed when other methods fail.

Closed reduction is often possible in babies up to eighteen months old. When DDH is diagnosed later, the chances increase that an operation is needed. Closed reduction is the standard practice and will apply weight traction to the limbs with the child either on a frame or in gallows suspension. While traction is maintained gradually to abduct the hips, a little more each day, until 80 degrees of abduction is reached. This will take three to four weeks.[5][6][13]

Another option for treatment is diet. Dietary supplements are often used. Oral glucosamine comes from shellfish (although vegetarian options exist) and may help rebuild cartilage. An anti-inflammatory diet may help reduce inflammation. Ginger, garlic, green tea and Omega-3 fatty acids may have anti-inflammatory effects and can be found in fish and fish oil supplements, as well as in flaxseed, squash, collard greens, nuts, broccoli, cauliflower and spinach. Certain foods in the nightshade family can increase inflammation. The most common edible nightshades are tomato, potato, eggplant and red pepper.

Also anti-inflammatory medications or NSAIDs can be used. Patients can also be given steroid shots to reduce inflammation and pain. However some studies have shown that repeated use of cortisone can weaken tendons and soften cartilage.

Surgical Management[edit | edit source]

The other option of surgery is open reduction. This is used when a closed reduction fails to correct the joint. In an open reduction, the surgeon cuts into the hip capsule and re-positions the femoral head. Once the hip is sutured, a spica cast is applied for 4 months or longer to stabilize the hip.[13]

Once children are older soft tissue surgery isn’t possible anymore. Then there are the bony surgeries. There are two options which are reshaping and redirecting. With the reshaping treatment the hip socket is reshaped to increase the hip congruency. This is only possible with children who have pliable bones. Redirecting is performed on older patients who no longer have pliable bones. The surgeon repositions the socket but does not change its shape.

Older children have the option between two surgeries. The first reshapes, redirects or salvages bone in order to preserve the natural joint for as long as possible. Shelf and Chiari osteotomy are some of those salvage procedures. In these cases non-articular cartilage is used to help hold the hip in place. The cartilage added in these procedures is fibrocartilage rather than true articular cartilage. The second option is a hip replacement.

Arthroscopy is a surgical procedure often performed on the soft tissue surrounding the joint. It's a minimally invasive procedure that can postpone more invasive surgery. In some cases where the dysplasia is relatively non-advanced, arthroscopy can rule out the need for further surgery altogether. Also the use of stem cells is possible. These stem cells are used in grafting or by seeding porous arthroplasty prosthesis with autologous fibroblasts or chondrocyte progenitor cells to assist in firmly anchoring the artificial material in the bone bed.[15]

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

The treatment of hip dysplasia depends on the age of the child. The goal of the treatment is to position the hip in the proper position. Once the proper position is obtained the doctor will hold the hip in that position and that will allow the body to adapt to the new position. The younger the child, the better capacity to adapt the hip, and the better chance of full recovery.

When the child is younger then 6 month the use of a special brace called a Pavlik harness is used.[16] The brace holds the hips of the baby in the correct position. Over time the joint begins normal formation. About 90% of the newborns treated with the Pavlik harness will recover fully. Also a Frejka Pillow is used but is not indicated in all forms of hip dysplasia.

Complications mainly arise because the sheet of the iliopsoas muscle pushes the circumflex artery against the neck of the femur and decreases blood flow to the femoral head. When the child is older then 6 months the Pavlik harness may not be successful. In that case a surgeon will place the hip in the proper position under anesthesia. Once in this position the child will be placed in a spica cast. The spica cast is similar to the Pavlik harness but allows less movement.

A treatment that isn’t often used is traction. Traction exists of the application of a force to stretch certain parts of the body in a certain direction. This will soften the tissue around the caput femoris and will allow the caput femoris to move back in the acetabulum. Traction consists of pulleys, strings, weights, and a metal frame attached over or on the bed. Traction is most often used for approximately 10 to 14 days. The application of ice on the painful regions helps to numb pain and reduces the inflammation.[17]

Regular, low- or non-impact exercise such as swimming, aquatic therapy or cycling train strength and range of motion. Strong muscles will act like shock absorbers and provide greater support for the hip. Weight loss for those overweight can significantly reduce the stress on the hip and reduce pain. Physical therapy can be used to increase strength and flexibility around the joint which will decrease pain.[17] Physical therapy can also be used to teach the body to better align itself which will lead to a decrease of stress on the joint.

In addition, there is another therapy called hippotherapy. Hippotherapy is a specialized therapy treatment strategy that uses a horse's movement to influence the patient/client in a various number of ways.[18] During hippotherapy, functional riding skills are not taught; the client sits on the horseback and physically accommodates to the three-dimensional movements of the horse's walk. Hippotherapy is shown to motivate the child to engage in therapy, maintain the child's willingness to participate and provide a playful environment while facilitating pain free movement.[19]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 Nandhagopal T, De Cicco FL. Developmental Dysplasia Of The Hip. StatPearls [Internet]. 2020 Oct 10. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK563157/(accessed 11.10.2021)

- ↑ Byrd J. Gross anatomy. In: Byrd J, editor. Operative Hip Arthroscopy. 2nd ed. New York: Springer Science + Business Media, Inc; 2004.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Quality Improvement, Subcommittee on Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip, Clinical Practice Guideline : Early detection of developmental Dysplasia of the hip, Official Journal of the American Academy of Pediatrics Vol 105 No 4 April 2000, downloaded from pediatrics.applications.org at Swets Blackwell 30680247 on November 23, 2011. Level of evidence: 1 A

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Radiopedia Developmental dysplasia of the hip Available: https://radiopaedia.org/articles/developmental-dysplasia-of-the-hip (accessed 11.10.2021)

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 John Crawford Adams, David L. Hamblem, Outline of Orthopaedics, Churcill Livingstone, 1995, twelfth edition, p. 292 – 301.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 John Crawford Adams, David L. Hamblem, Outline of Orthopaedics, Churcill Livingstone, 2001, thirteenth edition, p. 305 – 312.

- ↑ J.Maheshwari. Essential Orthopaedics. 6th edition. Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers,2019

- ↑ Andreas Roposch, Liang Q. Liu, Fritz Hefti, M. P. Clarke, John H. Wedge, Standardized Diagnostic Criteria for Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip in Early Infancy, Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research (2011) 469:3451 – 3461. Level of evidence: 1 B

- ↑ Harry B. Skinner, Current : Diagnosis and treatment in Orthopedics, McGraw Hill Medical Publishing Division, 2000, second edition, p.1537 – 1540.

- ↑ Delaney LR, Karmazyn B. Developmental dysplasia of the hip: background and the utility of ultrasound. InSeminars in Ultrasound, CT and MRI 2011 Apr 1 (Vol. 32, No. 2, pp. 151-156). WB Saunders.

- ↑ Brurås KR, Aukland SM, Markestad T, Sera F, Dezateux C, Rosendahl K. Newborns with sonographically dysplastic and potentially unstable hips: 6-year follow-up of an RCT. Pediatrics. 2011 Feb 9:peds-2010.

- ↑ Dr. Anisuddin Bhatti. Ortolani's Click & Barlow's Maneuver. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mv_kLqZSGdo [last accessed 04/05/13]

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Lawrence W. Current surgical diagnosis & treatment. Appleton & Lange; 1994.

- ↑ Childrens Hospital. Angela and hip dysplasia - Boston Children's Hospital. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bShtxYFdERQ [last accessed 04/05/13]

- ↑ van der Linden MH, Kruyt MC, Sakkers RJ, de Koning TJ, Öner FC, Castelein RM. Orthopaedic management of Hurler’s disease after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: a systematic review. Journal of inherited metabolic disease. 2011 Jun 1;34(3):657-69.

- ↑ Guille JT, Pizzutillo PD, MacEwen GD. Developmental dysplasia of the hip from birth to six months. JAAOS-Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2000 Jul 1;8(4):232-42.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Enseki KR, Martin RL, Draovitch P, Kelly BT, Philippon MJ, Schenker ML. The hip joint: arthroscopic procedures and postoperative rehabilitation. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy. 2006 Jul;36(7):516-25.

- ↑ Debuse D, Chandler C, Gibb C. An exploration of German and British physiotherapists' views on the effects of hippotherapy and their measurement. Physiotherapy theory and practice. 2005 Jan 1;21(4):219-42.

- ↑ Roy Aldridge PT, Farley Schweighart SP, Megan Easley SP. The effects of hippotherapy on motor performance and function in an individual with bilateral developmental dysplasia of the Hip (DDH). J Phys Ther. 2011; 2:54-63