Mindfulness Meditation in Chronic Pain Management

Original Editor - User Name

Top Contributors - Merinda Rodseth, Kim Jackson, Tarina van der Stockt, Vidya Acharya, Jess Bell and Lucinda hampton

Introduction[edit | edit source]

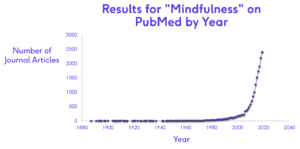

Evidence for the use of mindfulness has grown rapidly since its introduction to the Western world around 1979, with more than 2500 studies currently available on mindfulness (Figure 1).

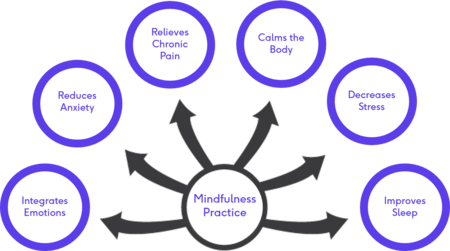

Mindfulness-Based Interventions (MBI) are showing promising results in supporting mental health needs even in the absence of psychological disorders and have become a more popular, cost-effective method to provide the support.[1][2] The benefits of MBI are well established and include:[3][4][5][6]

- Decreased anxiety and depression

- Relieve of stress and psychological distress

- Increased coping abilities

- Alleviation of pain

- Decreased negative affect

- Enhanced cognitive control

- Emotion regulation

Figure 2. Benefits of Mindfulness Practice

Cognitive Changes associated with Mindfulness[edit | edit source]

The greatest impact of mindfulness is its effect on the neural plasticity of the brain. Several changes in brain activation has been documented with the practice of mindfulness, allowing us to also “see” the benefits of MBI as is evident on functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) (Tang 2015, Bauer 2019). However, the study designs vary greatly with the use of different MBI and therefore the locations of the reported effects are diverse and spread over multiple regions of the brain (Tang 2015).The brain regions most consistently altered with MBI include (Tang 2015, Young 2018, Gotink 2016, Zimmerman 2019)

Table 1: Neural changes associated with mindfulness practice

| Region of the brain | Effect with MBI | Function of the region |

| Insula and sensory cortices | Increased activation | Body awareness (interoception)

Emotional processing Self-awareness Interpersonal experience |

| Anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) | Increased activation | Higher order cognitive processes

Attention and attention regulation Self and emotional regulation Cognitive distancing - associated with non-judgemental acceptance |

| Prefrontal cortex | Increased activation | Higher order cognitive processes

Attention and attention regulation Emotion regulation Meta-awareness & reappraisal Reasoning and decision making Functional connectivity with the salience network Downregulation of amygdala responses |

| Hippocampus | Increased activation

Increased volume |

Memory processes |

| Amygdala | Decreased activation

Decrease in volume/size |

Fight-or-flight reaction

Fear response Stress response Adds emotional value to sensory input - emotional processing |

Greater stress is associated with greater amygdala activation. Down-regulation of the amygdala is what underscores the reduction in stress seen with MBSR (Gotink 2016). Mindfulness is therefore not simply about paying attention. The way in which we use this focus of the mind ultimately changes the function and the structure of the brain (Siegel 2007). Just as we can train our muscles to grow, we can “train” our brains as is evident in the studies about mindfulness.

Mindfulness and Pain[edit | edit source]

Chronic pain poses a significant therapeutic challenge and has been declared a public health problem, placing burdens not only on those experiencing pain, but also society as a whole (Edwards 2016, Smith 2020). Chronic pain is estimated to affect more than 100 million adults at any given time in the United States, with chronic back pain being the most commonly reported chronic pain complaint (Smith 2020, Edwards 2016, MClintock 2019, Qaseem 2017, Zeidan 2019). Chronic pain is also one of the primary causes of disability and decreased quality of life, resulting in a cost of more than $600 billion dollars annually in the United States alone (Edwards 2016, McClintock 2019). Opioid medication is frequently prescribed in order to manage pain and its potential consequences, which contributed to many other problems including the “opioid epidemic” of opioid misuse, addiction and opioid-related deaths due to patients overdosing (McClintock 2019, Smith 2020). Mindfulness, as a nonpharmacologic option, is receiving increased interest in the management of pain (McClintock 2019, Ngamkham 2018, Zeidan 2019)

Chronic pain is complex in nature, involving many physical and psychological factors (Smith 2020, Zeidan 2015). It is associated with sleep disturbances, obesity and weight gain, chronic fatigue, limited physical functionality and decreased quality of life (Smith 2020). Individuals suffering from a variety of chronically painful conditions are also at an increased risk for anxiety, depression and other affective disorders (Edwards 2016, MClintock 2019, Hilton 2017). The International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) (ref) defines pain as “An unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with, or resembling that associated with, actual or potential tissue damage.” Treatment of pain should therefore also be multifaceted to address both the sensory component as well as the affective/emotional experience of pain. Treatments targeted at the negative affect associated with chronic pain are therefore hypothesised to not only positively influence the emotional distress but also influence the frequency and intensity of pain (Edwards 2016). Mindfulness as a multifaceted intervention is therefore ideally placed to have a positive effect on pain and pain affect without the negative effects associated with pharmacological interventions such as opioids.(Edwards 2016, MClintock 2019, Elvery 2017, Zeidan 2019).

MBSR is consistently showing positive improvements in pain management (Edwards 2016, Zeidan 2015, Smith 2020). Several studies have looked at the effect of MBI on various chronic conditions and various chronically painful conditions including chronic low back pain (LBP) (Niazi 2011). Several of these studies can be found in Table 2. Table 2. Studies on the effect of MBI

| Study | Year | Participants and design | Intervention | Results |

| Niazi | 2011 | Systematic review

18 studies looking at chronic illness (cancer, hypertension, diabetes, HIV/AIDS, chronic pain, skin disorders) |

MBSR alone or with other treatments | Improvement in chronic conditions |

| Zeidan et al | 2011 | 15 participants | 4days mindfulness meditation training | Reduction in pain intensity (40%)

Reduced pain unpleasantness (57%) |

| Zeidan et al | 2015 | 75 participants | 4 groups: Mindfulness meditation, placebo, sham meditation and control | Mindfulness meditation group - significant reduction in pain intensity (27%)

Reduced pain unpleasantness (44%) |

| Morone et al | 2016 | 282 participants with chronic LBP | MBSR and control group (8 weeks, 1.5 hrs once weekly) | Significant improvements in disability and quality of life |

| Cherkin et al | 2016 | Randomised controlled trial

342 participants with chronic LBP |

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT)

MBSR 8 weekly 2-hour groups Control group (usual care) |

MBST and CBT equivalent in reducing pain and improving function showing greater improvements compared to usual care |

| Zgierska et al | 2016 | 35 participants with chronic LBP | Meditation cognitive therapy and control (8 weeks, 2hrs/w)

Control/usual care group |

Significant decrease in pain intensity (short and long-term) |

| Anheyer | 2017 | Systematic review & Meta-analysis

7 RCTs with patients with LBP |

MBSR associated with short-term improvements in pain intensity and physical functioning | |

| Banth & Ardebil | 2018 | 88 patients with NSCLBP | MBSR (8 sessions) and control (usual care) | MBSR significant reduction in pain and improvement in physical and mental quality of life |

| Smith & Hoon Langen | 2020 | Systematic review

12 studies in patients with chronic LBP |

Mindfulness-based interventions

Control groups |

Improvement in pain scores and quality of life after mindfulness interventions |

| Qaseem et al | 2017 | Systematic review to establish practice guidelines | MBSR recommended for patients with chronic LBP |

MBIs are suggested to have greater effects on pain-related catastrophizing, especially in the presence of high levels of pain intensity, compared to traditional cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) approaches (Edwards 2016, Elvery 2017). In general, participants practicing mindfulness (especially MBSR) for chronic pain, displayed significantly improved outcomes of pain measures as well as quality of life and mental health measures compared to matched control groups (Smith 2020). Patients with chronic pain who engaged in mindfulness practice were generally found to be able to find new ways of living with and accepting pain, resulting in a less negative impact on their daily lives. (Smith 2020) The need for methodologically sound studies on MBI for patients with chronic pain is however reiterated in many studies (Hilton 2017).

Mechanism of Pain Reduction through Mindfulness Practice[edit | edit source]

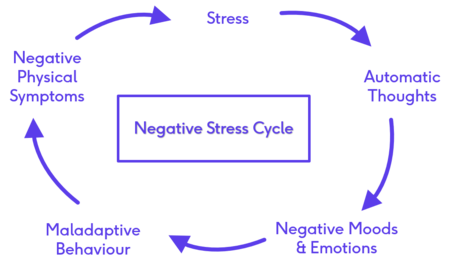

Exploring the mechanisms by which mindfulness influences stress and pain, necessitate an explanation of the negative stress cycle which develops as a result of the long-term and unrelenting presence of stress and pain. (Shrey talk) The negative stress cycle is set off by the occurrence of a stressful event which is often not relenting. The patient enters into a cycle of automatic thoughts about this event (the stress/pain) which leads to negative moods and emotions, ultimately resulting in maladaptive behaviours which often end up sustaining this cycle by worsening their symptoms (Figure 3).(Shrey talk, Edwards 2016)

Figure 3. The Negative Stress Cycle

The practice of mindfulness is able to break this cycle by interrupting the “automatic thoughts” stage achieved through turning off the autopilot mode of living and guiding the awareness back to the present moment with an attitude of non-judgement and non-reactance. (Shrey talk, Smith 2020) MBSR proposes that mindfulness practice “will allow for the “uncoupling” of the bottom-up, afferent, sensory-driven components of pain from the top-down, psychological, cortically-driven components of pain” (Smith 2020). This suggests that awareness can result in a dissociation between the physical sensation of pain from the emotions and thoughts previously attached to pain (Smith 2020, Banth 2018). The goal of mindfulness, therefore, is not to eliminate the stress or pain, but to teach the patient self-awareness and alternate responses to stress and pain by embracing the pain, accepting the moment for what it is (Shrey talk, Smith 2020). By making peace with the pain, the patient is able to better manage the pain with fewer negative coping responses (including fear and anxiety) (Shrey talk, Smith 2020,Banth 2018).

Pain reduction through mindfulness meditation also utilises different neural mechanisms as compared to placebo analgesia (Zeidan 2015). Besides its proposed influence on pain affect, mindfulness-based pain relief also engages brain mechanisms involved in mediating the cognitive modulation of pain, which include: (McLIntock 2019, Zeiden 2011, 2015, 2019)

- decreased activity in neural regions associated with low-level nociceptive processing (eg thalamus)

- Increased activity in neural regions associated with interoceptive awareness (eg right anterior insula)

- Top-down executive control (eg ACC)

- Cognitive reappraisal of sensory information (eg orbitofrontal cortex)

The ultimate strength of mindfulness lies in the neural changes it causes. Keeping in mind that “nerves that fire together, wire together”, repetitive practice of mindfulness meditation leads to changes in neural pathways resulting in a more calm, accepting disposition towards life (Shrey talk).

Several studies have found that long-term meditation practice can lead to increased pain threshold values and lower pain sensitivity even while the practitioners are not engaged in mindfulness practice (Zeidan 2019). Grant et al (2011) studied Zen meditators using fMRI and found that long-term meditators had distinct neural pathways which predicted their low pain sensitivity. These neural pathways suggest a reduction in cognitive-emotional and evaluative processing during aversive stimulation which relates to reduced connectivity (greater “decoupling”) between the cognitive and evaluative areas of pain processing and the sensory component of pain processing (Grant 2011, Shrey talk, Zeidan 2019). These Zen meditators still preserved the capacity to feel the pain on a sensory level, but displayed reduced affective appraisal, or less activation in the evaluative and emotional areas of the brain, related to the painful event (Zeidan 2019, Grant 2011). These pathways also correspond well to the psychological construct (present moment, non-judgemental awareness) of mindfulness which resulted in the meditators possessing quieter and less reactive brains (Grant 2011, Shrey talk)

Key messages[edit | edit source]

- Mindfulness and neuroscience research has exploded in recent years

- Mindfulness has many benefits, especially for stress-reduction

- Through the wonder of neuroplasticity, mindfulness has shown to have a direct effect on our physiology and our psychology

Resources[edit | edit source]

- bulleted list

- x

or

- numbered list

- x

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Dunning D.L., Griffiths K., Kuyken W., Crane C., Foulkes L., Parker J., Dalgleish T. Research Review: The effects of mindfulness‐based interventions on cognition and mental health in children and adolescents–a meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2019; 60(3), pp.244-258. DOI:10.1111/jcpp.12980

- ↑ Nunes A, Castro SL, Limpo T. A review of mindfulness-based apps for children. Mindfulness. 2020 Sep;11(9):2089-101. DOI:10.1007/s12671-020-01410-w

- ↑ Spinelli C, Wisener M, Khoury B. Mindfulness training for healthcare professionals and trainees: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2019 May 1;120:29-38. DOI:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2019.03.003

- ↑ Marusak HA, Elrahal F, Peters CA, Kundu P, Lombardo MV, Calhoun VD, Goldberg EK, Cohen C, Taub JW, Rabinak CA. Mindfulness and dynamic functional neural connectivity in children and adolescents. Behavioural brain research. 2018 Jan 15;336:211-8. DOI:10.1016/j.bbr.2017.09.010

- ↑ Geronimi EM, Arellano B, Woodruff-Borden J. Relating mindfulness and executive function in children. Clinical child psychology and psychiatry. 2020 Apr;25(2):435-45. DOI:10.1177/135910451983373

- ↑ Zeidan F, Baumgartner JN, Coghill RC. The neural mechanisms of mindfulness-based pain relief: a functional magnetic resonance imaging-based review and primer. Pain reports. 2019 Jul;4(4). DOI:10.1097/PR9.0000000000000759