Lumbar Conditions in Ballet Dancers: Difference between revisions

Diana Yang (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 37: | Line 37: | ||

== Spondylolisthesis == | == Spondylolisthesis == | ||

Spondylolisthesis is closely related to Spondylolysis. It refers to the forward slip of the vertebrae <ref>Gottschlich, L.M. and Young, C.C. (2011). Spine Injuries in Dancers. ''Current Sports Medicine Reports'', 10(1), pp.40–44. doi:<nowiki>https://doi.org/10.1249/jsr.0b013e318205e08b</nowiki>. | |||

</ref>. This is due to stress fractures (Spondylolysis) causing a weakening of the vertebral column to the extent that the vertebrae cannot maintain its normal position, resulting vertebrae to move outside of its normal anatomical place <ref>https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/spondylolisthesis/</ref>. Spondylolisthesis can be defineD by four grades, grade I is when there 1 to 25% slippage, grade II up to 50% slippage and grade III is up to 75% in slippage and lastly grade IV is when there is greater than 75% slippage<ref>Hu, S.S., Tribus, C.B., Diab, M. and Ghanayem, A.J. (2008). Spondylolisthesis and Spondylolysis. ''JBJS'', [online] 90(3), p.656. Available at: <nowiki>https://journals.lww.com/jbjsjournal/pages/articleviewer.aspx?year=2008&issue=03000&article=00025&type=Fulltext</nowiki> [Accessed 18 May 2023]. | |||

</ref>. | |||

Wiltse et al developed six classifications for Spondylolisthesis and dancers are likely to develop grade II Isthmic spondylolithesis. Grade II is further divided into three parts, A which is fatigue fractures of the pars, B which refers to elongated but intact pars and C which is acute fracture of the pars. <ref>Wiltse, L.L. and Winter, R.B. (1983). Terminology and measurement of spondylolisthesis. ''The Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery'', 65(6), pp.768–772. doi:<nowiki>https://doi.org/10.2106/00004623-198365060-00007</nowiki>. | |||

</ref>Type II Is greatly associated with flexion, twisting and most notable hyperextension activities seen in dancers. <ref>Wiltse, L.L. and Winter, R.B. (1983). Terminology and measurement of spondylolisthesis. ''The Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery'', 65(6), pp.768–772. doi:<nowiki>https://doi.org/10.2106/00004623-198365060-00007</nowiki>. | |||

</ref> | |||

== Management Recommendations == | == Management Recommendations == | ||

Revision as of 11:38, 18 May 2023

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Lumbar hyperlordosis refers to the exaggerated curvature at the lumber spine, representing a faulty posture. It is associated with

- Increased lumbar lordosis

- Increased anterior pelvic tilt

This leads to an increased hip flexion, and can hyperextend the knee joints. Increased plantarflexion at the foot then occurs due to this knee position.[1]

The sagittal lumbar curvature in ballet dancers can alter to compensate for limited range of motion in certain joints in order to achieve the desired posture, this can result in hyperlordosis in the lumbar spine.[2][3][4][5] Movements such as turn out (or first position), and arabesque that often require dancers to be in positions that are anatomically adverse.[3][6]

Lumbar Conditions in Ballet Dancers[edit | edit source]

Lumbar hyperlordosis in ballet dancers can lead to low back pain (LBP),[7] and joint trauma[8] such as spondylolysis, or trauma to the pars interarticularis, the intervertebral discs, and the facet joints. [6] It predisposes dancers to muscle spasm, piriformis syndrome, and other spinal conditions like spondylolisthesis.[9]

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

The lumbar spine consists of 5 vertebrae, situated between the thoracic spine and the sacrum. Each vertebra consists of a vertebral body and a neural arch, with the body anterior to the arch (FIGURE). When viewed superiorly, the body is wider transversely, and the neural arch is triangular shaped (especially distinguishable at L5). The facet angles range from 120 – 150 degrees relative to the sagittal plane, and consistently decrease from L1 to L5. [10]

As with the rest of the spinal column, the articulations consist of the intervertebral disc anteriorly, and a pair of facet joints posteriorly. The ligaments (FIGURE) stabilize the spine as one unit, including the following major ligaments

- Anterior longitudinal ligament: originating from the skull and inserting into the upper part of the sacrum, connecting the whole anterior aspect of the vertebral bodies and intervertebral discs

- Posterior longitudinal ligament: originating from the occipital bone and inserting into the sacrum, connecting the whole posterior aspect of the vertebral bodies and discs

- Ligamentum flava: present in between the laminae of each vertebra

- Supraspinous and Interspinous ligaments: connecting the spinous processes of each vertebra

The mean angle of lumbar lordosis is said to be around 48-61 degrees.[11] Lumbar hyperlordosis is indicated when the angle is greater than 68 degrees.[1] FIGURE demonstrate the comparison between the normal lumbar curvature and a increased lordosis in the lumbar spine.

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

Hyperlordosis[edit | edit source]

Relevant Literature[edit | edit source]

The extreme ranges of motion required during dancing and gymnastics may contribute to the participants' high lumbar lordosis. [12] Ambegaonkar (2014) examined 17 female dancers using 2-dimensional sagittal plane photographs and the Watson Maconncha Posture Analysis Instrument. A strength of this study are the experimental methods due to be found reliable and accurate in previous studies and are commonly used in a clinical and research setting for assessing lumbar lordosis. Results showed among dancers, 9 had significant lumber lordosis deviations and 5 had moderate deviations. This shows the extreme ranges of motion required during the technique when dancing may contribute to the participants high lumbar lordosis. However, the limitation of this study entails focusing that it only examined female dancers, therefore the findings may not be applicable to other populations as well as not investigating the influence of age, training onset, training regimes, or other factors on lumbar lordosis. Additionally, the study only examined lumbar lordosis levels at one point in time, future research could enquire longitudinal studies to determine if there is a relationship between lumbar lordosis levels and lumbar injury incidence in dancers. Another study by Byran and Smith (1992) discusses the patterns of weakness and tightness in certain muscle groups in ballet dancers that contribute to hyper lordotic posture such as lumbodorsal fascia and hamstring can occur during the growth spurt phase of development. This could be common as the average starting ages ranging from 5 to 11 years old with full time training typically beginning around 14 to 15 years old [13] [14] Due to the demands of dance involve extreme and repetitive lumber hyperextension alongside areas of weak and tight muscles during their growth spurt where full time intense training begins, may result in a hyper lordotic posture.[15] However, the limitation of this study entails focusing that it only examined female dancers, therefore the findings may not be applicable to other populations.

Spondylolysis[edit | edit source]

Spondylolysis is an isolated defect in the neural arch of the vertebrae [16]. It refers to a stress fracture of the pars interarticularis of a vertebra in the spine. Lumbar spondylolysis results from repetitive, mechanical stress on the lower back, however, biological factors are not ruled out [16]. The defect can either be asymptomatic or associated with significant low back pain [17]. The pars interarticularis is the weakest area of the vertebrae, making it the most susceptible to injury. Spondylolysis can occur in one of the pars interarticularis or in both of them in one vertebra, meaning that is can be unilateral or bilateral [18]. The vast majority of spondylolitic defects occur at the L5 level (85-95%) and L4 being the second most commonly involved level (5-15%)[19]. It is of of the most common types of skeletal injury in paediatric dancers and gymnasts.

Spondylolisthesis[edit | edit source]

Spondylolisthesis is closely related to Spondylolysis. It refers to the forward slip of the vertebrae [20]. This is due to stress fractures (Spondylolysis) causing a weakening of the vertebral column to the extent that the vertebrae cannot maintain its normal position, resulting vertebrae to move outside of its normal anatomical place [21]. Spondylolisthesis can be defineD by four grades, grade I is when there 1 to 25% slippage, grade II up to 50% slippage and grade III is up to 75% in slippage and lastly grade IV is when there is greater than 75% slippage[22].

Wiltse et al developed six classifications for Spondylolisthesis and dancers are likely to develop grade II Isthmic spondylolithesis. Grade II is further divided into three parts, A which is fatigue fractures of the pars, B which refers to elongated but intact pars and C which is acute fracture of the pars. [23]Type II Is greatly associated with flexion, twisting and most notable hyperextension activities seen in dancers. [24]

Management Recommendations[edit | edit source]

Strengthening[edit | edit source]

Positioning[edit | edit source]

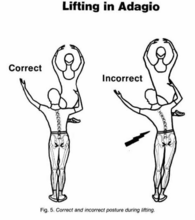

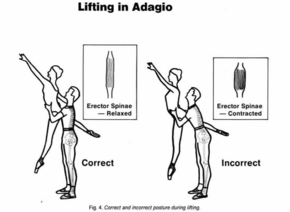

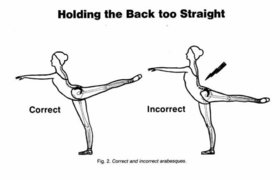

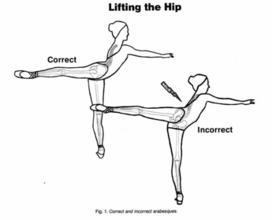

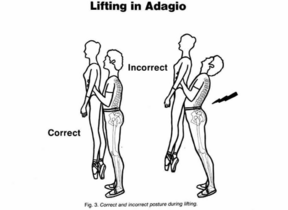

Gelabert (1986) explains that in a ballet dancer, if the iliofemoral ligament in front of the hip joint restricts hypertension of the leg and the external rotation at the hip socket, the dancer will often disguise this limitation by lifting the hip to the side like shown in Figure 1. The repetition of this incorrect movement has a massive effect on low back afflictions and multiplies when the back is kept too straight shown in Figure 2. This is performed instead of the correct position by increasing the inclination of the pelvis forward as the leg raises backwards. This study shows in 100 cases of low back syndromes in ballet dancers, 45% are related to those who lift at the hip in arabesque and other movements of the leg backwards and 25% of those who forcefully try to raise their leg above 90 degrees while keeping their back too straight. It has been found that these injuries will arise faster with individuals with longer backs and tight hip muscles and ligaments, which is often found in male physiques. Alongside this, spasm of the lumbar muscles occurs usually from faults of technique in hyperextension. Tension within the upper spine and chest muscles will be reflected in the thoracic region and to lumbar, pelvis and to the legs, increasing fatigue which causes inefficient breathing patterns and inclining the spine to strain. The impact of this is instrumental to male dancers when lifting, this is shown in Figure 3,4, and 5, it can lead to weak muscle pull, inefficient energy use and an increased risk of low back strain.

Stretching[edit | edit source]

Conclusion[edit | edit source]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Bogduk, N. (2005) Clinical Anatomy of the Lumbar Spine and Sacrum. 4th edition. Elsevier: Churchill Livingstone.

- ↑ Skallerud, A., Brumbaugh, A., Fudalla, S., Parker, T., Robertson, K. & Pepin, M.-E. (2022) Comparing Lumbar Lordosis in Functional Dance Positions in Collegiate Dancers with and without Low Back Pain. J Dance Med Sci. 26 (3), 191–201.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Livanelioglu, A., Otman, S., Yakut, Y. & Uygur, F. (1998) The Effects of Classical Ballet Training on the Lumbar Region. Journal of Dance Medicine & Science. 2 (2), 52–55.

- ↑ Cejudo, A., Gómez-Lozano, S., de Baranda, P.S., Vargas-Macías, A. & Santonja-Medina, F. (2021) Sagittal Integral Morphotype of Female Classical Ballet Dancers and Predictors of Sciatica and Low Back Pain. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 18 (9).

- ↑ Gamboa, J.M., Robert, L.A. & Fergus, A. (2008) Injury patterns in elite preprofessional ballet dancers and the utility of screening programs to identify risk characteristics. The Journal of orthopaedic and sports physical therapy. 38 (3), 126–136.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Milan, K.R. (1994) Injury in Ballet: A Review of Relevant Topics for the Physical Therapist. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 19 (2), 121–129.

- ↑ Pinnelli, M., Pulcinelli, M., Carnevale, A., Di Tocco, J., Massaroni, C., Schena, E., Longo, U.G. & Denaro, V. (2022) A Wearable System for Detecting Lumbar Hyperlordosis in Ballet Dancers: Design, Development and Feasibility Assessment. 2022 IEEE International Workshop on Metrology for Industry 4.0 and IoT, MetroInd 4.0 and IoT 2022 - Proceedings. 277–282.

- ↑ Roussel, N.A., Nijs, J., Mottram, S., Van Moorsel, A., Truijen, S. & Stassijns, G. (2009) Altered lumbopelvic movement control but not generalized joint hypermobility is associated with increased injury in dancers. A prospective study. Manual Therapy. 14 (6), 630–635.

- ↑ Gottschlich, L.M. & Young, C.C. (2011) Spine injuries in dancers. Current Sports Medicine Reports. 10 (1), 40–44.

- ↑ Ebraheim, N.A., Hassan, A., Lee, M. & Xu, R. (2004) Functional anatomy of the lumbar spine. Seminars in Pain Medicine. 2 (3), 131–137.

- ↑ Jentzsch, T., Geiger, J., König, M.A. & Werner, C.M.L. (2017) Hyperlordosis is Associated with Facet Joint Pathology at the Lower Lumbar Spine. Clinical Spine Surgery. 30 (3), 129–135.

- ↑ Ambegoankar, J. P. et al., 2014. Lumbar lordosis in female collegiate dancers and gymnasts. Medical problems of performing artists, 29(4), pp. 189-192.

- ↑ Hutchinson, C. U., Sachs-Ericsson, N. J. & Ericsson, A. K., 2013. Generalizable aspects of the development of expertise in ballet across countries and cultures: a perspective from the expert-performance approach. High Ability Studies, 24(1), pp. 21-47.

- ↑ Bernacki, J. L. et al., 2021. Risk Factors for Lower-Extremity Injuries in Female Ballet Dancers: A Systematic Review. Clinical Journal of Sports Medicine, 31(2), pp. 64-79.

- ↑ Bryan, N. & Smith, B. M., 1992. The ballet dancer. Occup Med: State of the Art Reviews, 7(1), pp. 67-75.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Berger, R. G. & Doyle, S. M., 2019. Spondylolysis 2019 update. Current Opinion in Pediatrics, 31(1), pp. 61-68.

- ↑ Syrmou, E. et al., 2010. Spondylolysis: A review and reappraisal. Hippokratia Quarterly Medical Journal, 14(1), pp. 17-21.

- ↑ Leone, A. et al., 2011. Lumbar spondylolysis: a review. Skeletal Radiology, Volume 40, pp. 683-700.

- ↑ Standaert, D. C. & Herring, S., 2000. Spondylolysis: a critical review. British Journal of Sports Medicine, Volume 34, pp. 415-422.

- ↑ Gottschlich, L.M. and Young, C.C. (2011). Spine Injuries in Dancers. Current Sports Medicine Reports, 10(1), pp.40–44. doi:https://doi.org/10.1249/jsr.0b013e318205e08b.

- ↑ https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/spondylolisthesis/

- ↑ Hu, S.S., Tribus, C.B., Diab, M. and Ghanayem, A.J. (2008). Spondylolisthesis and Spondylolysis. JBJS, [online] 90(3), p.656. Available at: https://journals.lww.com/jbjsjournal/pages/articleviewer.aspx?year=2008&issue=03000&article=00025&type=Fulltext [Accessed 18 May 2023].

- ↑ Wiltse, L.L. and Winter, R.B. (1983). Terminology and measurement of spondylolisthesis. The Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery, 65(6), pp.768–772. doi:https://doi.org/10.2106/00004623-198365060-00007.

- ↑ Wiltse, L.L. and Winter, R.B. (1983). Terminology and measurement of spondylolisthesis. The Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery, 65(6), pp.768–772. doi:https://doi.org/10.2106/00004623-198365060-00007.