Anterior Cord Syndrome: Difference between revisions

(Edited Clinical Presentation) |

(Edited Clinical Presentation) |

||

| Line 35: | Line 35: | ||

== Clinical Presentation == | == Clinical Presentation == | ||

The clinical presentation of ASA syndrome differs with the level of | The clinical presentation of ASA syndrome differs with the level of ischemia. There are varying degrees of muscle weakness and dissociated sensory loss: pain sensation is decreased or absent while proprioception is relatively or completely spared. Due to the anatomical proximity of the pyramidal and spinothalamic tracts in the cord, the loss of motor power usually mirrors that of pain. Seldom, this syndrome can also be the result of a central spinal cord infarct. | ||

Other signs of the syndrome will depend on the location where the cord was injured. Broadly,there is a chance for autonomic dysreflexia , movement and sexual impairments, neuropathic pain, and bladder and bowel dysfunction | Other signs of the syndrome will depend on the location where the cord was injured. Broadly, there is a chance for autonomic dysreflexia , movement and sexual impairments, neuropathic pain, and bladder and bowel dysfunction. | ||

=== Motor === | === Motor === | ||

* | * Below the spinal cord level of injury, there is bilateral motor dysfunction since both halves of the anterior spinal cord receive vascular supply from one midline anterior spinal artery. Rare cases of ASA have been reported with unilateral symptomatology this could be due to collateralization from one posterior spinal artery or occlusion of unilateral sulcal arteries. <ref>Pearl NA, Dubensky L. Anterior Cord Syndrome. [Updated 2021 Aug 26]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan-</ref>. | ||

* The clinical onset of ASA is abrupt, with pain. Depending upon th area of the infarct, the severity of dysfunction varies from flaccid paraplegia or tetraplegia below the lesion. | |||

* The clinical onset of ASA is abrupt, with pain, flaccid paraplegia or tetraplegia below the lesion | * Early motor deficits due to spinal shock consist of flaccidity with absent reflexes, followed by a gradual return of the reflexes and increased tone or spasticity. Typically, the first presenting symptom is acute back pain, the area mostly corresponds with the level of the injury in the spinal cord. | ||

* | |||

=== Sensory === | === Sensory === | ||

alterations in temperature and pain sensation.[7] Vibration, fine touch, and proprioception sensory modalities will not be affected, as these are relayed by the dorsal columns which are located in the posterior one-third of the cord and are supplied by the two posterior spinal arteries. | |||

Revision as of 18:29, 3 January 2022

Introduction[edit | edit source]

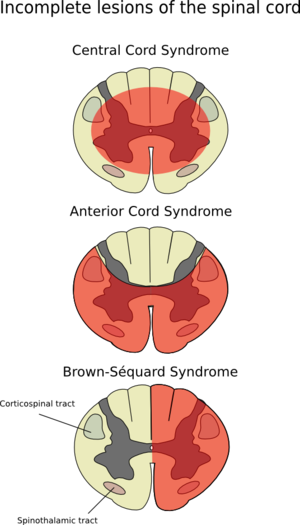

Anterior cord syndrome referred to as Anterior spinal artery syndrome (ASAS) or ventral cord syndrome (VCS)[1]. ASAS is an incomplete spinal cord injury(SCI) that is often related to flexion injuries of the cervical region that result in infarction of the anterior two thirds of the cord and/or its vascular supply from the anterior spinal artery.[2] Patients present with impairments in the pain and temperature sensations while the vibratory and proprioceptive sensations are preserved. Motor deficits are observable both at and below the level of injury.[3]

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

ASAS is caused by ischemia within the anterior spinal artery (ASA), which supplies blood to the anterior 2/3rd of the spinal cord. The anterior spinal artery, with a few radicular artery contributions, supplies blood to the bilateral anterior and lateral horns of the spinal cord, as well as the bilateral spinothalamic tracts and corticospinal tracts. The anterior horns and corticospinal tracts control the somatic motor system from the neck to the feet. The lateral horns span T1-L2 of the spinal cord and sheathe the neuronal cell bodies of the sympathetic nervous system. The spinothalamic tracts carry pain and temperature sensory information.

Aetiology[edit | edit source]

Pathological process[edit | edit source]

The ventral two-thirds of the cord contains essential tracts for the[4] proper functioning of the central nervous system (CNS); injury impairs the actions of these tracts. Damage to the efferent corticospinal tract results in impairment of motor function whereas damage to the spinocerebellar and spinothalamic tracts cause sensory deficits.

Mechanisms of injury[edit | edit source]

- Occlusion of the Anterior Spinal Artery results in:

- Disruption of the blood flow through spinal artery causes → spinal cord tissue ischemia and infarction from the level of disruption of flow leading to →Infarction of the corticospinal and spinothalamic pathways → ACS[5]

- Vertebral/burst fractures :

- Resulting in forces coming from above or below the vertebral body (depending on the injury)

- Nucleus pulposus of the intervertebral disc is forced into the vertebral body → shatters outward (burst) fracture → spinal cord injury related to the force and direction of the traumatic event

- Posteriorly displaced fracture fragments → ACS

Physiological Sequelae[edit | edit source]

The occlusion/hypo-perfusion of the ASA results in:

- Ischemic and reperfusion injuries→causes damage to the spinal cord by activation of the glial cells, disruption of the blood-spinal cord barrier (BSCB) disruption, tissue edema, and influx of neutrophils.

- Additional neuronal death results from the associated inflammatory response, oxidative stress, and activation of apoptosis pathways, which, together, are also termed ‘reperfusion injury'.

The mechanical trauma to the spinal cord occurs in injury during two phases:

- The initial direct trauma results in→ acute compression and disruption of vasculature and axons.

- In the second phase, a cascade of events triggers as a result of the injury, including hemorrhage, edema, inflammation, demyelination, pathologic changes in the neurons and oligodendroglia, as well as microglial and astrocyte activation in an early stage.

- A later stage consists of scar formation, Wallerian degeneration, development of cysts and syrinx, and schwannosis.[1][8]

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

The clinical presentation of ASA syndrome differs with the level of ischemia. There are varying degrees of muscle weakness and dissociated sensory loss: pain sensation is decreased or absent while proprioception is relatively or completely spared. Due to the anatomical proximity of the pyramidal and spinothalamic tracts in the cord, the loss of motor power usually mirrors that of pain. Seldom, this syndrome can also be the result of a central spinal cord infarct.

Other signs of the syndrome will depend on the location where the cord was injured. Broadly, there is a chance for autonomic dysreflexia , movement and sexual impairments, neuropathic pain, and bladder and bowel dysfunction.

Motor[edit | edit source]

- Below the spinal cord level of injury, there is bilateral motor dysfunction since both halves of the anterior spinal cord receive vascular supply from one midline anterior spinal artery. Rare cases of ASA have been reported with unilateral symptomatology this could be due to collateralization from one posterior spinal artery or occlusion of unilateral sulcal arteries. [6].

- The clinical onset of ASA is abrupt, with pain. Depending upon th area of the infarct, the severity of dysfunction varies from flaccid paraplegia or tetraplegia below the lesion.

- Early motor deficits due to spinal shock consist of flaccidity with absent reflexes, followed by a gradual return of the reflexes and increased tone or spasticity. Typically, the first presenting symptom is acute back pain, the area mostly corresponds with the level of the injury in the spinal cord.

Sensory[edit | edit source]

alterations in temperature and pain sensation.[7] Vibration, fine touch, and proprioception sensory modalities will not be affected, as these are relayed by the dorsal columns which are located in the posterior one-third of the cord and are supplied by the two posterior spinal arteries.

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

Management/Interventions[edit | edit source]

Non-surgical[edit | edit source]

Surgical[edit | edit source]

Prognosis[edit | edit source]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

- Central cord syndrome

- Dorsal cord syndrome

- Brown-Séquard syndrome

- Conus medullaris syndrome

- Cauda equina syndrome

- Transverse myelitis

- Guillain-Barré syndrome

- Multiple sclerosis

- Spinal epidural abscess

- Epidural hematoma

- Disk herniation

- Spinal cord neoplasm

- Meningitis/encephalitis

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Santana JA, Dalal K. Ventral Cord Syndrome. 2021 Aug 26. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan–.

- ↑ Deutsch JE, O’Sullivan SB. Stroke. In: O'Sullivan SB, Schmitz TJ, Fulk G, editors. Physical Rehabilitation.7th edition. Philadelphia: FA Davis; 2019. p.860

- ↑ Santana JA, Dalal K. Ventral Cord Syndrome. [Updated 2021 Aug 26]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan-.

- ↑ Sandoval JI, De Jesus O. Anterior Spinal Artery Syndrome. 2021 Aug 30. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan–.

- ↑ Sandoval JI, De Jesus O. Anterior Spinal Artery Syndrome. [Updated 2021 Aug 30]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan-.

- ↑ Pearl NA, Dubensky L. Anterior Cord Syndrome. [Updated 2021 Aug 26]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan-