Fecal Incontinence: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 37: | Line 37: | ||

* unable to stop the urge to defecate, which comes on so suddenly, patient may comment that that they don't make it to the toilet in time | * unable to stop the urge to defecate, which comes on so suddenly, patient may comment that that they don't make it to the toilet in time | ||

* May state that they have additional bowel issues, such as, diarrhea, constipation, gas and bloating | * May state that they have additional bowel issues, such as, diarrhea, constipation, gas and bloating | ||

Objective: | '''Objective:''' | ||

Physical examination – The physical examination should include pelvic examination, inspection of the perianal area, and a digital rectal examination (DRE). | |||

* Pelvic Examination: | |||

* Perianal Examination: | |||

* DRE: | |||

Physical examination – The physical examination should include pelvic examination, inspection of the perianal area, and a digital rectal examination. | |||

==Management/Interventions== | ==Management/Interventions== | ||

| Line 54: | Line 51: | ||

'''Physician''' | '''Physician''' | ||

'''Education''' | Endoanal ultrasound: to detect functional and structural abnormalities (eg, anal sphincter injury), if a significant sphinchter injury is already present | ||

''',Education''' | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

Revision as of 19:02, 31 March 2019

- Page is currently under construction, please check back later for updates

- Specifically, Fecal Incontinence associated with pregnancy and childbirth

Definition[edit | edit source]

The International Continence Society provides the following definitions of bowel incontinence:[1]

- Fecal incontinence (FI) is defined as the involuntary loss of feces (liquid or solid). FI is also referred to as accidental bowel leakage.

- Anal incontinence (AI) is defined as the involuntary loss of feces and/or flatus.

Etiology[edit | edit source]

Fecal incontinence (FI) and anal incontinence (AI) affect all age groups of both men and women, including pregnant and postpartum women, and have a significant impact on quality of life.

During Pregnancy:

During the late stages of pregnancy, physiological changes such as, increased transit time leading to altered stool consistency and increased intra-abdominal pressure, may contribute changes in incontinence for women with preexisting pelvic floor or anal sphincter dysfunction.

Childbirth:

During childbirth, pelvic floor muscle and/or nerve injury may lead to incontinence. Injury of the neural innervation to the pelvic floor muscles can lead to the inability to use these muscles adequately. Damage to the pudendal nerve can occur through can become stretched and compressed, with demyelination and subsequent denervation, due to the by the passage of the fetal head through the pelvis.[2][3] Anal sphincter laceration can lead to FI, however, not all anal sphincter injuries result in FI.[4] Additionally, the use of instruments (ie. forceps or vacuum) during vaginal delivery can increase the risk or FI or AI, particularly if an obstetric anal sphincter injury occurred.[5][6][7] When comparing the use of forceps versus vacuum during vaginal delivery, one study found the use of forceps significantly increased the risk of FI.[8] There remains controversy in the literature with regards to the effect of vaginal delivery versus cesarean birth and its affect on FI or AI.[9][10]

Post-Partum:

Incontinence symptoms are more common during the postpartum period than during pregnancy.[11]

Other Risk Factors for developing FI:[12][13][14]

- Older age

- Diarrhea

- Fecal urgency

- Urinary incontinence

- Diabetes mellitus

- Hormone therapy

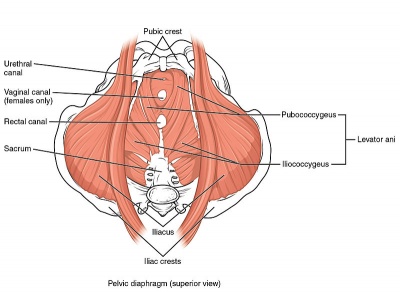

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

Please see the page "Pelvic Floor Anatomy," for further details regarding anatomy.

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Symptoms:[15]

- unable to stop the urge to defecate, which comes on so suddenly, patient may comment that that they don't make it to the toilet in time

- May state that they have additional bowel issues, such as, diarrhea, constipation, gas and bloating

Objective:

Physical examination – The physical examination should include pelvic examination, inspection of the perianal area, and a digital rectal examination (DRE).

- Pelvic Examination:

- Perianal Examination:

- DRE:

Management/Interventions[edit | edit source]

Diet

Physiotherapist

Physician

Endoanal ultrasound: to detect functional and structural abnormalities (eg, anal sphincter injury), if a significant sphinchter injury is already present

,Education

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ The International Continence Society. Glossary. Available from: https://www.ics.org/glossary?q=fecal%20incontinence

- ↑ Sultan AH, Kamm MA, Hudson CN. Pudendal nerve damage during labour: prospective study before and after childbirth. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 1994 Jan 1;101(1):22-8.

- ↑ Allen RE, Hosker GL, Smith AR, Warrell DW. Pelvic floor damage and childbirth: a neurophysiological study. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 1990 Sep;97(9):770-9.

- ↑ Oberwalder M, Connor J, Wexner SD. Meta‐analysis to determine the incidence of obstetric anal sphincter damage. British journal of surgery. 2003 Nov;90(11):1333-7.

- ↑ Larsson C, Hedberg CL, Lundgren E, Söderström L, TunÓn K, Nordin P. Anal incontinence after caesarean and vaginal delivery in Sweden: a national population-based study. The Lancet. 2019 Mar 23;393(10177):1233-9.

- ↑ Pretlove SJ, Thompson PJ, Toozs‐Hobson PM, Radley S, Khan KS. Does the mode of delivery predispose women to anal incontinence in the first year postpartum? A comparative systematic review. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2008 Mar 1;115(4):421-34.

- ↑ Blomquist JL, Muñoz A, Carroll M, Handa VL. Association of Delivery Mode With Pelvic Floor Disorders After Childbirth. Jama. 2018 Dec 18;320(23):2438-47.

- ↑ Fitzpatrick M, Behan M, O'Connell PR, O'Herlihy C. Randomised clinical trial to assess anal sphincter function following forceps or vacuum assisted vaginal delivery. BJOG: an international journal of obstetrics & gynaecology. 2003 Apr 1;110(4):424-9.

- ↑ Larsson C, Hedberg CL, Lundgren E, Söderström L, TunÓn K, Nordin P. Anal incontinence after caesarean and vaginal delivery in Sweden: a national population-based study. The Lancet. 2019 Mar 23;393(10177):1233-9.

- ↑ Blomquist JL, Muñoz A, Carroll M, Handa VL. Association of Delivery Mode With Pelvic Floor Disorders After Childbirth. Jama. 2018 Dec 18;320(23):2438-47.

- ↑ Brown SJ, Gartland D, Donath S, MacArthur C. Fecal incontinence during the first 12 months postpartum: complex causal pathways and implications for clinical practice. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2012 Feb 1;119(2):240-9.

- ↑ Ng KS, Sivakumaran Y, Nassar N, Gladman MA. Fecal incontinence: community prevalence and associated factors—a systematic review. Diseases of the Colon & Rectum. 2015 Dec 1;58(12):1194-209.

- ↑ Halland M, Koloski NA, Jones M, Byles J, Chiarelli P, Forder P, Talley NJ. Prevalence correlates and impact of fecal incontinence among older women. Diseases of the Colon & Rectum. 2013 Sep 1;56(9):1080-6.

- ↑ Staller K, Townsend MK, Khalili H, Mehta R, Grodstein F, Whitehead WE, Matthews CA, Kuo B, Chan AT. Menopausal hormone therapy is associated with increased risk of fecal incontinence in women after menopause. Gastroenterology. 2017 Jun 1;152(8):1915-21.

- ↑ Mayo Clinic. Fecal Incontinence. Available from: https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/fecal-incontinence/symptoms-causes/syc-20351397