Spondyloarthropathy--AS: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| (48 intermediate revisions by 5 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

<div class="editorbox"> | |||

<div class="editorbox"> | '''Original Editors ''' | ||

'''Original Editors ''' | |||

'''Top Contributors''' - {{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}} | '''Top Contributors''' - {{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}} | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

== Definition/Description == | == Definition/Description == | ||

Spondyloarthropathies are a diverse group of inflammatory arthritides that share certain genetic predisposing factors and clinical features. The group primarily includes [[Ankylosing Spondylitis (Axial Spondyloarthritis)|Ankylosing Spondylitis]], reactive arthritis (including [[Reactive Arthritis|Reiter’s syndrome]]), psoriatic arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease–associated spondyloarthropathy, and undifferentiated spondyloarthropathy.<ref name="p1">Goodman C, Snyder T. Differential Diagnosis for Physical Therapists: Screening for Referral. St. Louis, MO: Saunders Elsevier: 2007. 539</ref> <ref name="p2">Kataria R.K. et al., Spondyloarthropathies. Am Fam Physician, 2004, 69 (12):2853-2860 Level of Evidence 5</ref> Level 5 | |||

The primary pathologic sites are the sacroiliac joints, the bony insertions of the annulus fibrosis of the intervertebral discs, and the apophyseal joints of the spine.<ref name="p1" /> | |||

<br> | <br>[[Ankylosing Spondylitis (Axial Spondyloarthritis)|Ankylosing Spondylitis (AS) also]] known as Marie- Strumpell disease or bamboo spine, is an inflammatory arthropathy of the axial skeleton, usually involving the sacroiliac joints, apophyseal joints, costovertebral joints, and intervertebral disc articulations.<ref name="p2" /> AS is a chronic progressing inflammatory disease that causes inflammation of the spinal joints that can lead to severe, chronic pain and discomfort. In advanced stages, the inflammation can lead to new bone formation of the spine, causing the spine to fuse in a fixed position often creating a forward stooped posture.<ref name="p2" /><br> | ||

[[Image:Spondy 1.png|center|Fig. 1]] | |||

== Clinically Relevant Anatomy == | |||

The vertebral column exists of 24 vertebrae: seven [[Cervical Vertebrae|cervical vertebrae]], twelve thoracic vertebrae and five [[Lumbar Vertebrae|lumbar vertebrae]]. The vertebrae are joined together by ligaments and separated by intervertebral discs. The discs exist of an inner nucleus pulposus and an outer annulus fibrosis, consisting of fibrocartilage rings.<br>Patients with spondyloarthropathy have a high propensity for inflammation at the sites where tendons, ligaments and joint capsules attach to the bone. These sites are known as entheses. <ref name="p3">Benjamin M. and McGonagle D., The anatomical basis for disease localization in seronegative spondyloarthropathy at entheses and related sites. J. Anat., 2001. Level of Evidence 5</ref>Level 5<br> | |||

The [[Sacroiliac Joint|sacroiliac joint]] consists of a cartilaginous part and a fibrous (or ligamentous) compartment with very strong anterior and posterior sacroiliac ligaments. This makes the SIJ an amphiarthrosis with movement restricted to slight rotation and translation. Another specific feature of the SIJs is that two different types of cartilage cover the two articular surfaces. While the sacral cartilage is purely hyaline, the iliac side is covered by a mixture of hyaline and fibrous cartilage. Due to its fibrocartilaginous components, the sacroiliac joint is a so-called articular enthesis.<ref name="p4">Hermann K.G.A., Bollow M., Magnetic Resonance Imaging of Sacroiliitis in Patients with Spondyloarthritis: Correlation with Anatomy and Histology. Fortschr Röntgenstr, 2014, 186:3, 230-237 Level of Evidence 1B</ref>Level 1B | |||

== Epidemiology /Etiology == | |||

Ankylosing spondylitis (the most common spondyloarthropathy) has a prevalence of 0.1 to 0.2 percent in the general U.S. population and is related to the prevalence of HLA-B27. Diagnostic criteria for the spondyloarthropathies have been developed for research purposes, the criteria rarely are almost not used in clinical practice. There is no laboratory test to diagnose ankylosing spondylitis but the HLA-B27 gene has been found to be present in about 90 to 95 percent of affected white patients in central Europe and North America <ref name="p2" />Level 5 | |||

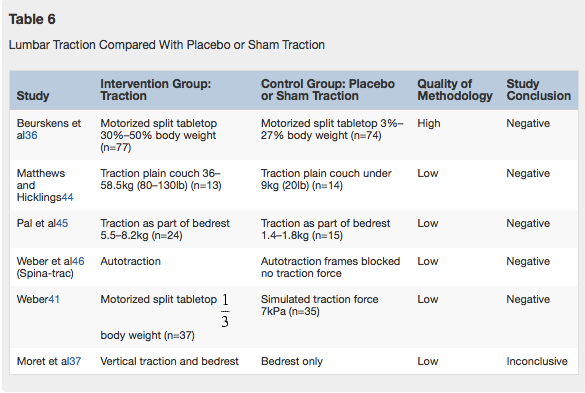

<br>AS is 3 times more common in men than in women and most often begins between the ages of 20-40.<ref name="p5">Beers MH, et. al. eds. The Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy. 18th ed. Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck Research Laboratories; 2006.</ref> <ref name="p2" /> (Level 5) Recent studies have shown that AS may be just as prevalent in women, but diagnosed less often because of a milder disease course with fewer spinal problems and more involvement of joints such as the knees and ankles. Prevalence of AS is nearly 2 million people or 0.1% to 0.2% of the general population in the United States. It occurs more often in Caucasians and some Native American than in African Americans, Asians, or other nonwhite groups.<ref name="p1" /> AS is 10 to 20 times more common with first degree relatives of AS patients than in the general population. The risk of AS in first degree relatives with the HLA-B27 allele is about 20%.<ref name="p5" /> <br>[[Image:Tabel.png|center|Table 1]]<br> | |||

== Characteristics/Clinical Presentation == | |||

The most characteristic feature of spondyloarthropathies is inflammatory back pain. Another characteristic feature is enthesitis, which involves inflammation at sites where tendons, ligaments, or joint capsules attach to bone.<ref name="p2" /> Level 5 <ref name="p5" /> Level 5 <br>Additional clinical features include inflammatory back pain, dactylitis, and extra-articular manifestations such as uveitis and skin rash.<ref name="p2" /> Level 5<br><br>There can also be buttock, or hip pain and stiffness for more than 3 months in a person, usually male under 40 years of age.<ref name="p1" /> It is mostly worse in the morning, lasting more than 1 hour and is described as a dull ache that is poorly localized, but it can be intermittently sharp or jolting. Overtime pain can become severe and constant and coughing, sneezing, and twisting motions may worsen the pain. Pain may radiate to the thighs, but does not typically go below the knee. Buttock pain is often unilateral, but may alternate from side to side.<ref name="p2" /> | |||

Paravertebral muscle spasm, aching, and stiffness are common, making sacrioliac areas and spinous process very tender upon palpation.<ref name="p1" /> A flexed posture eases the back pain and paraspinal muscle spasm; therefore, kyphosis is common in untreated patients.<ref name="p5" /> <br> | |||

Enthesitis (inflammation of tendons, ligaments, and capsular attachments to bone) may cause pain or stiffness and restriction of mobility in the axial skeleton.<ref name="p2" /> Dactylitis (inflammation of an entire digit), commonly termed “sausage digit,” also occurs in the spondyloarthropathies and is thought to arise from joint and tenosynovial inflammation <ref name="p2" /> Level 5.<br>Since AS is a systemic disease an intermittent low grade fever, fatigue, or weight loss can occur.<ref name="p1" /> | |||

In advanced stages the spine can become fused and a loss of normal lordosis with accompanying increased kyphosis of the thoracic spine, painful limitations of cervical joint motion, and loss of spine flexibility in all planes of motion. A decrease in chest wall excursion less than 2 cm could be an indicator of AS because chest wall excursion is an indicator of decreased axial skeleton mobility.<ref name="p2" /> | |||

Anterior uveitis is the most frequent extra-articular manifestation, occurring in 25 to 30 percent of patients. The uveitis usually is acute, unilateral, and recurrent. Eye pain, red eye, blurry vision, photophobia, and increased lacrimation are presenting signs. Cardiac manifestations include aortic and mitral root dilatation, with regurgitation and conduction defects. Fibrosis may develop in the upper lobes of the lungs in patients with longstanding disease. <ref name="p6">Sieper J., et al. Ankylosing spondylitis: an overview. Ann Rheum Dis 2002;61, 8-18. Level of Evidence 5</ref> Level 5 | |||

[[Image:Spondy4.jpg|center]]<br><br> | |||

== Differential Diagnosis == | |||

Most Common differential diagnosis<ref name="p2" /> | |||

| *[[Rheumatoid Arthritis|Rheumatoid arthritis]] | ||

*Psoriasis | |||

*[[Reactive Arthritis|Reiter's syndrome]] | |||

*Fracture | |||

*Osteoarthritis | |||

*Inflammatory bowel disease<ref name="p7">Jarvik, J. G., & Deyo, R. A. (2002). Diagnostic evaluation of low back pain with emphasis on imaging. Annals of internal medicine, 137(7), 586-597. Level of Evidence 3B</ref> : Ulcerative colitis and [[Crohn's Disease|Crohn’s disease]]<br> | |||

*Psoriatic spondylitis <ref name="p7" /> | |||

*[[Scheuermann's Kyphosis|Scheuermann’s disease/|Scheuermann's Kyphosis]] <ref name="p7" /> | |||

*[[Paget's Disease|Paget’s disease]] <ref name="p7" /> Level 5 | |||

<br> Differential Diagnosis of Ankylosing Spondylitis and Thoracic Spinal Stenosis<ref name="p7" /> | |||

{| width="700" border="1" cellpadding="1" cellspacing="1" align="center" | |||

|- | |||

! scope="row" | | |||

! scope="col" | Ankylosing Spondylitis | |||

! scope="col" | Thoracic Spinal Stenosis | |||

|- | |||

! scope="row" | History | |||

| Morning stiffness<br>Intermittent aching pain<br>Male predominance<br>Sharp pain<br>Bilateral sacroiliac pain may refer to posterior thigh | |||

| Intermittent aching pain<br>Pain may refer to both legs with walking | |||

|- | |||

! scope="row" | Active movements | |||

| Restricted | |||

| May be normal | |||

|- | |||

! scope="row" | Passive movements | |||

| Restricted | |||

| May be normal | |||

|- | |||

! scope="row" | Resisted isometric<br>movements | |||

| Normal | |||

| Normal | |||

|- | |||

! scope="row" | Special tests | |||

| None | |||

| [[Bicycle Test of Van Gelderen|Bicycle test of van Gelderen]] may be positive<br>Stoop test may be positive | |||

|- | |||

! scope="row" | Reflexes | |||

| Normal | |||

| May be affected in long standing cases | |||

|- | |||

! scope="row" | Sensory deficit | |||

| None | |||

| Usually temporary | |||

|- | |||

! scope="row" | Diagnostic imaging | |||

| Plain films are diagnostic | |||

| Computed tomography scans are diagnostic | |||

|} | |||

<br> | <br> | ||

<br> | In the early stages of ankylosing spondylitis, the changes in the sacroiliac joint are similar to that of rheumatoid arthritis, however the changes are almost always bilateral and symmetrical. This fact allows ankylosing spondylitis to be distinguished from psoriasis, Reiter's syndrome, and infection. Changes at the sacroiliac joint occur throughout the joint, but are predominantly found on the iliac side. | ||

== Diagnostic Procedures == | |||

AS can be diagnosed by the modified New York criteria, the patient must have radiographic evidence of sacroiliitis and one of the following: (1) restriction of the lumbar spine motion in both the sagittal and frontal planes, (2) restriction of chest expansion (usually < 2.5 cm) (3) a history of back pain includes onset at <40 year, gradual onset, morning stiffness, improvement with activity, and duration >3 months.<ref name="p8">Beers MH, ed. The Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy, 18th edition. Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck and CO; 2006</ref><br> | |||

Imaging tests | |||

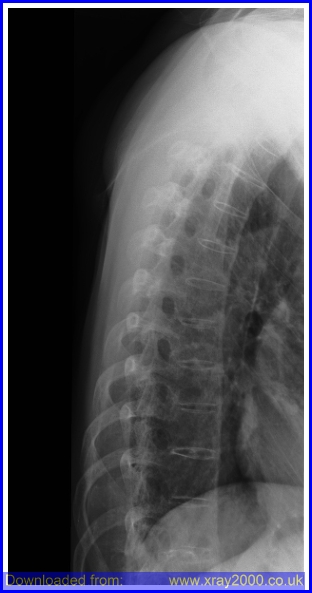

*X-rays. Radiographic findsing of symmetric, bilateral sacroiliitis include blurring of joint margins, extaarticular sclerosis, erosion, and joint space narrowing. As bony tissue bridges the vertebral bodies and posterior arches, the lumbar and thoracic spine creates a “bamboo spine” image on radiographs.<ref name="p2" /> | |||

*Computerized tomography (CT). CT scans combine X-ray views taken from many different angles into a cross-sectional image of internal structures. CT scans provide more detail, and more radiation exposure, than do plain X-rays.<ref name="p2" /> | |||

*Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Intraarticular inflammation, early cartilage changes and underlying bone marrow edema and osteitis can be seen using an MRI technique called short tau inversion recovery (STIR). Using radio waves and a strong magnetic field, MRI scans are better at visualizing soft tissues such as cartilage. <ref name="p2" /> | |||

*Lab tests. There is no laboratory test to diagnose ankylosing spondylitis but the HLA-B27 gene has been found to be present in about 90 to 95 percent of affected white patients in central Europe and North America <ref name="p2" /> Level 5. The presence of the HLA-B27 antigen is a useful adjunct to the diagnosis, but cannot be diagnostic alone.<ref name="p2" /> | |||

Four out of five positive responses to the following questions may help with the determining of AS: | |||

#Did the back discomfort begin before age 40 | |||

#Did the discomfort begin slowly | |||

#Has the discomfort persisted for 3 months | |||

#Was morning stiffness a problem | |||

#Did the discomfort improve with exercise | |||

Specificity= 0.82, Sensitivity =0.23<br> LR for four out of five positive responses = 1.3<ref name="p6" /> | |||

Chronic low back pain (LBP), the leading symptom of ankylosing spondylitis (AS) and undifferentiated axial spondyloarthritis (SpA), precedes the development of radiographic sacroiliitis, sometimes by many years. <ref name="p4" /> Level 4<br> | |||

= | It is also noted that patients with ankylosing spondylitis (AS) have an increased risk of bone loss and vertebral fractures. <ref name="p7" /> Level 3B | ||

In summary, the diagnostic procedures for Ankylosing Spondylitis include: | |||

< | *Imaging tests such as X-ray and CT scans | ||

*HLA B27 gene presence (genetical factor) | |||

*Blood samples with focus on CRP levels | |||

*BASDAI, BASMI and BASFI <ref name="p0" /> Level 1B | |||

[[Image:Spine-t ankylosing spondylitis.jpg|center]] | |||

== Outcome Measures == | |||

== | Modified Health Assessment Questionnaire (MHAQ)<br>Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) <ref name="p0">El Miedany Y. Towards a multidimensional patient reported outcome measures assessment: Development and validation of a questionnaire for patients with ankylosing spondylitis/spondyloarthritis. Elsevier, 2010, Volume 77, Issue 6 Level of Evidence 1B</ref> Level 1B<br>ASQoL <ref name="p0" /> Level 1B <br>Assessment of the duration of morning stiffness using “0–10 cm” horizontal visual analogue scale, as well as duration of morning stiffness in minutes. <ref name="p0" /> Level 1B<br>Self-report joint tenderness: this is carried out on a joint diagram with the joint names written beside it as a guide and the patient is asked to tick the box matching the painful joint(s) [30] Level 1B<br>Self-reported soft tissue tenderness (enthesitis): this is carried out on a skeleton model and the patient is asked to highlight the places he feels pain. <ref name="p0" /> Level 1B<br> | ||

== Examination == | |||

Physical examination of the spine involves the cervical, thoracic and lumbar region. <br>Cervical involvement often occurs late. The stooping of the neck can be measured by the occiput-to-wall distance. The patient stands with the back and heels against the wall and the distance between the back of the head and the wall is measured. [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rOR70O_zTdA Video occiput-to-wall test]<br>The thoracic spine can be tested by the chest expansion. It is measured at the fourth intercostal space and in women just below the breasts. The patient should be asked to force a maximal inspiration and expiration and the difference in chest expansion is measured. A chest expansion of less than 5 cm is suspicious and < 2.5 cm is abnormal and raises the possibility of AS unless there is another reason for it, like emphysema. The normal thoracic kyphosis of the dorsal spine is accentuated. The costovertebral, costotransverse and manubriosternal joints should be palpated to detect inflammation which causes pain on palpitation.<br>The lumbar spine can be tested by the [[Schober_Test|Schober’s test]]. This is performed by making a mark between the posterior superior iliac spines at the 5th lumbar spinous process. A second mark is placed 10 cm above the first one and the patient is asked to bend forward with extended knees. The distance between the two marks increases from 10 to at least 15 cm in normal people, but only to 13 or less in case of AS. <ref name="p1" /> Level 5<br><br> | |||

== Medical Management == | |||

According to Braun et al <ref name="Braun">Braun, J. von, Van Den Berg, R., Baraliakos, X., et al. 2010 update of the ASAS/EULAR recommendations for the management of ankylosing spondylitis. Annals of the rheumatic diseases, 2011, vol. 70, no 6, p. 896-904. | |||

Level of Evidence 5</ref> (2010, Level of Evidence 5) the overarching principles of the management of patients with AS are: | |||

*Requirement of a multidisciplinary treatment coordinated by the rheumatologist. | |||

*The primary goal is to maximise long term health-related quality of life. Therefore it is important to control symptoms and inflammation, prevent progressive structural damage, preserve/normalise function and social participation. | |||

*The treatment should aim at the best care and requisites a shared decision between the patient and the rheumatologist. | |||

*A combination of non-pharmacological and pharmacological treatment modalities is required. | |||

1. General treatment | |||

The treatment of patients with AS should be individualised according to: | |||

- | *The present manifestations of the disease (peripheral, axial, entheseal, extra-articular symptoms and signs). | ||

*The level of current symptoms, prognostic indicators and clinical findings. | |||

*The general clinical status (gender, age, comorbidity, psychosocial factors, concomitant medications). | |||

2. Disease monitoring | |||

The disease monitoring of patients with AS should include: | |||

*Patient history (eg, questionnaires) | |||

*Laboratory tests | |||

*Clinical parameters | |||

*Imaging | |||

*The frequency of monitoring should be individualised depending on: course of symptoms, treatment and severity | |||

3. Non-pharmacological treatment | |||

- | *Patient education and regular exercise form the cornerstone of non-pharmacological treatment of patients with AS. | ||

*Home exercises are effective. However, physical therapy with supervised exercises, land or water based, individually or in a group, should be preferred as these are more effective than home exercises. | |||

*Self-help groups and patient associations may be useful. | |||

4. Extra-articular manifestations and comorbidities | |||

*Psoriasis, uveitis and IBD are some of the frequently observed extra-articular manifestations. They should be managed in collaboration with the respective specialists. | |||

*Rheumatologists should be aware of the increased risk of cardiovascular disease and osteoporosis in patients with AS. | |||

5. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs | |||

<br> | *For AS patients with pain and stiffness, NSAID, including Coxibs, are recommended as first-line drug treatment. | ||

*For patients with persistently active, symptomatic disease, continuous treatment with NSAID is preferred.<br> | |||

6. Analgesics: after previously recommended treatments have failed, are contraindicated, and/or poorly tolerated.<br><br>7. Anti-TNF therapy | |||

*According to the ASAS recommendations, anti-TNF therapy should be given to patients with persistently high disease activity despite conventional treatments.<br> | |||

*Shifting to a second TNF blocker may be beneficial, especially in patients with loss of response. | |||

*No evidence exists to support the use of biological agents other than TNF inhibitors in AS. | |||

8. Surgery | |||

*In patients with refractory pain or disability and radiographic evidence of structural damage, independent of age, total hip arthroplasty should be considered. | |||

*In patients with severe disabling deformity, spinal corrective osteotomy may be considered. | |||

*A spinal surgeon should be consulted in patients with AS and an acute vertebral fracture. | |||

9. Changes in the disease course: Other causes than inflammation (eg. spinal fracture) should be considered if a significant change in the course of the disease occurs and appropriate evaluation, including imaging, should be performed.<br> | |||

== Physical Therapy Management == | |||

Rehabilitation should be patient-centred. It should also enable the patient to achieve independence, social integration and improve quality of life. The aim of physical therapy and rehabilitation in AS is to: | |||

*Reduce discomfort and pain; | |||

*Maintain or improve endurance and muscular strength; | |||

*Maintain or improve mobility, flexibility and balance; | |||

*Maintain or improve physical fitness and social participation; | |||

*Prevent spinal curve abnormalities as well as spinal and joint deformities. <ref name="p2" /> Level 5 | |||

A multimodal physical therapy program including aerobic, stretching, education and pulmonary exercises in conjunction with routine medical management has been shown to produce greater improvements in spinal mobility, work capacity, and chest expansion compared with medical care alone.<ref name="p2" /> Evidence showed that aerobic training improved walking distance and aerobic capacity in patients with AS. However, Aerobic training did not provide additional benefits in functional capacity, mobility, disease activity, quality of life, and lipid levels when compared with stretching exercises alone (Jennings et al, 2015). Evidence also showed that passive stretching resulted in a significant increase in the range of movement (ROM) of the hip joints in all directions except flexion during the physiotherapy course. This increase in ROM could be maintained by patients who performed the stretching exercises on a regular basis <ref name="p3" /> Level 1B. Since the severity of AS is very different among individuals, there is no specific exercise program that showed the greatest improvements. Some studies showed that a 50 minute, three times a week multimodal exercise program showed significant improvements after 3 months in chest wall excursion, chin to chest distance, occiput to wall distance, and the modified Schober flexion test.<ref name="p2" /> | |||

| However, according to Ozgocmen et al. <ref name="p2" /> (Level 5) some key recommendations can be formulated for patients with AS: | ||

*Physiotherapy and rehabilitation should start as soon as AS is diagnosed. | |||

*Physiotherapy should be planned according to the patients’ needs, expectations and clinical status, as well as be commenced and monitored properly. | |||

*Physiotherapy should be performed as an inpatient or outpatient program in all patients, regardless of disease stage, and should be carried out in obedience with general rules and contraindications. | |||

*Lifelong regular exercises are the anchor of treatment. A combined regime of inpatient spa-exercise therapy followed by group physiotherapy is recommended for the highest benefit, and group physiotherapy is also favored to home exercises <ref name="p2" /> Level 5 <ref name="p5" />Level 5 | |||

*As mentioned before, the conventional protocols of physiotherapy including stretching, flexibility and breathing exercises, as well as pool and land-based exercises and accompanying recreational activities are recommended. | |||

*Physiotherapy modalities should be used as complementary therapies based on the experience gained from their use in other musculoskeletal disorders <ref name="p2" /> Level 5 | |||

<br> | '''EXERCISE TRAINING PROGRAM<br>'''A few recommended exercises for an individual with AS (Masiero et al, 2011) <ref name="p4" /> Level 1B: | ||

<br> | *Respiratory exercises (10min)<br>2 Series of 10 repetitions each:<br>1. Chest expansion<br>2. Deep breathing<br>3. Thoracic breathless<br>4. Expiratory breathless<br>5. Diaphragmatic breathing exercises and abdominal control <br>6. Scapular girdle muscle exercises ( i.e., shoulder elevation in combination with breathless) | ||

*Exercises to mobilize the vertebrae and limbs (15 min)<br>2 series of 10 repetitions each per mobilization. Performed lying and/or seated and/or standing and/or on all fours or walking pain-free. Spinal exercises can also be combined with respiratory exercises (i.e., deep breathing or expiratory breathless)<br>1. Cervical side: lateral flexion and rotation (right and left), extension <br>2. Thoraco-lumbar side: lateral-flexion, extension, rotation<br>3. Shoulder and upper limb side: ab/adduction, flexion, elevation, and circumduction<br>4. Coxofemoral, knee and ankle side: ab/adduction, rotation and flexion-extension | |||

*Balancing and proprioceptive exercises (10 min)<br>2 series of 10 repetitions: standing and walking | |||

== | *Postural exercises and spinal and limb muscle stretching and strengthening (15min)<br>2 repetitions of an average of about 30/40 seconds each for stretching. All exercises could be performed both lying and seated or on all fours or in a standing position with active and passive mobility, pain-free<br>1. Stretching exercises for the posterior muscle chain of the spine (thoraco-lumbar and all erector spine group, etc.) and anterior muscle chain of the spine (superior and inferior abdominal etc.) <br>2. Stretching exercises for the anterior girdle muscle chain (psoas, hamstring etc.) and posterior pelvic girdle muscle chain<br>3. Stretching of posterior and anterior muscles of lower limbs | ||

*Endurance training (10 min)<br>Walking, treadmill, cycling or swimming for a progressive duration on the basis of the patient’s functional capacity (low speed, without resistance). | |||

*Posture education can be a very important component to the patient to maintain an erect posture as well. <ref name="p2" /> | |||

*Aquatic therapy can be an excellent option for most patients to provide low impact extension and rotation principles.<ref name="p2" /> | |||

*Pain education can be a very important benefit to the patient as well (Masiero et al, 2011). <ref name="p4" /> Level 1B<br>Exercises that should be avoided include high impact and flexion exercises. Over exercising can be potentially harmful and could exacerbate the inflammatory process.<ref name="p2" /> | |||

'''<br>''' | <br>'''MANUAL THERAPY<br>'''Some have advocated the efficacy and use of gentle non-thrust manipulation in the spine.<br>Eight weeks of self- and manual mobilization improved chest expansion, posture and spine mobility in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. The physiotherapeutic intervention consisted initially of warming up the soft tissue of the back muscles (with vibrations via a vibrator) and gentle mobility exercises. This was followed by both active angular and passive mobility exercises in the physiological directions of the joints in the spinal column and in the chest wall in three directions of motion (flexion/ extension, lateral flexion and rotation) and in different starting positions (lying face down, sideways, on the back and in a sitting position). Passive mobility exercises consisted of general, angular movements and specific, translatory movements. Stretching of tight muscles was done using the contracting–relaxing method. Soft tissue treatment (manual massage) of the neck was performed followed by relaxation exercises in a standing position and resting for some minutes lying on the treatment bench <ref name="p5" /><br> | ||

== Key Research == | |||

Dagfinrud, H., Hagen, K. B., & Kvien, T. K. (2008). Physiotherapy interventions for ankylosing spondylitis. The Cochrane Library. | |||

Chang, W. D., Tsou, Y. A., & Lee, C. L. (2016). Comparison between specific exercises and physical therapy for managing patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF CLINICAL AND EXPERIMENTAL MEDICINE, 9(9), 17028-17039. | |||

Liang, H., Zhang, H., Ji, H., & Wang, C. (2015). Effects of home-based exercise intervention on health-related quality of life for patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a meta-analysis. Clinical rheumatology, 34(10), 1737-1744. | |||

O’Dwyer, T., O’Shea, F., & Wilson, F. (2014). Exercise therapy for spondyloarthritis: a systematic review. Rheumatology international, 34(7), 887-902. | |||

Martins, N. A., Furtado, G. E., Campos, M. J., Ferreira, J. P., Leitão, J. C., & Filaire, E. (2014). Exercise and ankylosing spondylitis with New York modified criteria: a systematic review of controlled trials with meta-analysis. Acta Reumatológica Portuguesa, 39(4). | |||

Nghiem, F. T., & Donohue, J. P. (2008). Rehabilitation in ankylosing spondylitis. Current opinion in rheumatology, 20(2), 203-207. | |||

Fernandez-de-las-Penas, C., Alonso-Blanco, C., Aguila-Maturana, A. M., Isabel-de-la-Llave-Rincon, A., Molero-Sanchez, A., & Miangolarra-Page, J. C. (2006). Exercise and ankylosing spondylitis—which exercises are appropriate? A critical review. Critical Reviews™ in Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine, 18(1). | |||

Stasinopoulos, D., Papadopoulos, K., Lamnisos, D., & Stergioulas, A. (2016). LLLT for the management of patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Lasers in medical science, 31(3), 459-469. | |||

Karamanlioğlu, D. Ş., Aktas, I., Ozkan, F. U., Kaysin, M., & Girgin, N. (2016). Effectiveness of ultrasound treatment applied with exercise therapy on patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Rheumatology international, 36(5), 653-661. | |||

Jennings, F., Oliveira, H. A., de Souza, M. C., da Graça Cruz, V., & Natour, J. (2015). Effects of Aerobic Training in Patients with Ankylosing Spondylitis. The Journal of rheumatology, 42(12), 2347-2353. | |||

Niedermann, K., Sidelnikov, E., Muggli, C., et al. (2013) Effect of cardiovascular training on fitness and perceived disease activity in people with ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis care & research, 65(11), 1844-1852.<br> | |||

<br> | <br> | ||

== Resources | == Resources == | ||

<br>Fig 1: http://www.physio-pedia.com/images/f/fe/Spondy_1.png<br>Table 1: Source 22 (Kataria et al., 2004)<br>Fig 2: http://www.physio-pedia.com/images/b/b0/Spondy4.jpg<br>Fig 3: http://www.physio-pedia.com/images/c/c5/Spine-t_ankylosing_spondylitis.jpg<br>Video occiput-to-wall test: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rOR70O_zTdA<br><br> | |||

== Clinical Bottom Line == | |||

Spondyloarthropathy is a group of multisystem inflammatory disorders affecting various joints including the spine, peripheral joints and periarticular structures. They are associated with extra-articular manifestations (for example a fever). The majority are HLA B27 positive (serological test) and Rheumatoid Factor (RF) negative. <br>There are 4 major seronegative spondyloarthropathies: | |||

*Ankylosing Spondylitis (AS): is the prototype and effects more men than women | |||

*Reiter’s Syndrome | |||

*Psoriatic Arthritis | |||

*Arthritis of Inflammatory Bowel Disease | |||

<br> | Sacroiliitis is a common manifestation in all of these disorders. <br>Although a triggering infection and immune mechanisms are thought to underlie most of the spondyloarthopathies, their pathogenesis remains obscure. <br>Physical examination of the spine involves the cervical, thoracic and lumbar region. The physician may ask the patient to bend the back in different ways, check the chest circumference and also may search for pain points by pressing on different portions of the pelvis. In doubt the physician effects different diagnostic procedures such as X-ray imaging, HLA B27 presence, CRP levels in blood samples. <br>The treatment for AS can be divided into: | ||

*Medication | |||

*Non steroid anti inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) | |||

*Anti – TNF therapy | |||

Physiotherapy is the best known non surgical therapeutic way of treating AS improving flexibility and physical strength. Surgery is only recommended in patients with chronic cases Most cases can be treated without surgery. <br><br> | |||

== References == | == References == | ||

<br> | |||

<references /> | <references /> | ||

[[Category: | [[Category:Vrije_Universiteit_Brussel_Project]] | ||

[[Category:Rheumatology]] | |||

Latest revision as of 03:36, 3 September 2023

Original Editors

Top Contributors - Adam Bockey, Elise Jespers, Elaine Lonnemann, Kim Jackson, Admin, 127.0.0.1, WikiSysop, Wendy Walker and Lucinda hampton

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

Spondyloarthropathies are a diverse group of inflammatory arthritides that share certain genetic predisposing factors and clinical features. The group primarily includes Ankylosing Spondylitis, reactive arthritis (including Reiter’s syndrome), psoriatic arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease–associated spondyloarthropathy, and undifferentiated spondyloarthropathy.[1] [2] Level 5

The primary pathologic sites are the sacroiliac joints, the bony insertions of the annulus fibrosis of the intervertebral discs, and the apophyseal joints of the spine.[1]

Ankylosing Spondylitis (AS) also known as Marie- Strumpell disease or bamboo spine, is an inflammatory arthropathy of the axial skeleton, usually involving the sacroiliac joints, apophyseal joints, costovertebral joints, and intervertebral disc articulations.[2] AS is a chronic progressing inflammatory disease that causes inflammation of the spinal joints that can lead to severe, chronic pain and discomfort. In advanced stages, the inflammation can lead to new bone formation of the spine, causing the spine to fuse in a fixed position often creating a forward stooped posture.[2]

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

The vertebral column exists of 24 vertebrae: seven cervical vertebrae, twelve thoracic vertebrae and five lumbar vertebrae. The vertebrae are joined together by ligaments and separated by intervertebral discs. The discs exist of an inner nucleus pulposus and an outer annulus fibrosis, consisting of fibrocartilage rings.

Patients with spondyloarthropathy have a high propensity for inflammation at the sites where tendons, ligaments and joint capsules attach to the bone. These sites are known as entheses. [3]Level 5

The sacroiliac joint consists of a cartilaginous part and a fibrous (or ligamentous) compartment with very strong anterior and posterior sacroiliac ligaments. This makes the SIJ an amphiarthrosis with movement restricted to slight rotation and translation. Another specific feature of the SIJs is that two different types of cartilage cover the two articular surfaces. While the sacral cartilage is purely hyaline, the iliac side is covered by a mixture of hyaline and fibrous cartilage. Due to its fibrocartilaginous components, the sacroiliac joint is a so-called articular enthesis.[4]Level 1B

Epidemiology /Etiology[edit | edit source]

Ankylosing spondylitis (the most common spondyloarthropathy) has a prevalence of 0.1 to 0.2 percent in the general U.S. population and is related to the prevalence of HLA-B27. Diagnostic criteria for the spondyloarthropathies have been developed for research purposes, the criteria rarely are almost not used in clinical practice. There is no laboratory test to diagnose ankylosing spondylitis but the HLA-B27 gene has been found to be present in about 90 to 95 percent of affected white patients in central Europe and North America [2]Level 5

AS is 3 times more common in men than in women and most often begins between the ages of 20-40.[5] [2] (Level 5) Recent studies have shown that AS may be just as prevalent in women, but diagnosed less often because of a milder disease course with fewer spinal problems and more involvement of joints such as the knees and ankles. Prevalence of AS is nearly 2 million people or 0.1% to 0.2% of the general population in the United States. It occurs more often in Caucasians and some Native American than in African Americans, Asians, or other nonwhite groups.[1] AS is 10 to 20 times more common with first degree relatives of AS patients than in the general population. The risk of AS in first degree relatives with the HLA-B27 allele is about 20%.[5]

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

The most characteristic feature of spondyloarthropathies is inflammatory back pain. Another characteristic feature is enthesitis, which involves inflammation at sites where tendons, ligaments, or joint capsules attach to bone.[2] Level 5 [5] Level 5

Additional clinical features include inflammatory back pain, dactylitis, and extra-articular manifestations such as uveitis and skin rash.[2] Level 5

There can also be buttock, or hip pain and stiffness for more than 3 months in a person, usually male under 40 years of age.[1] It is mostly worse in the morning, lasting more than 1 hour and is described as a dull ache that is poorly localized, but it can be intermittently sharp or jolting. Overtime pain can become severe and constant and coughing, sneezing, and twisting motions may worsen the pain. Pain may radiate to the thighs, but does not typically go below the knee. Buttock pain is often unilateral, but may alternate from side to side.[2]

Paravertebral muscle spasm, aching, and stiffness are common, making sacrioliac areas and spinous process very tender upon palpation.[1] A flexed posture eases the back pain and paraspinal muscle spasm; therefore, kyphosis is common in untreated patients.[5]

Enthesitis (inflammation of tendons, ligaments, and capsular attachments to bone) may cause pain or stiffness and restriction of mobility in the axial skeleton.[2] Dactylitis (inflammation of an entire digit), commonly termed “sausage digit,” also occurs in the spondyloarthropathies and is thought to arise from joint and tenosynovial inflammation [2] Level 5.

Since AS is a systemic disease an intermittent low grade fever, fatigue, or weight loss can occur.[1]

In advanced stages the spine can become fused and a loss of normal lordosis with accompanying increased kyphosis of the thoracic spine, painful limitations of cervical joint motion, and loss of spine flexibility in all planes of motion. A decrease in chest wall excursion less than 2 cm could be an indicator of AS because chest wall excursion is an indicator of decreased axial skeleton mobility.[2]

Anterior uveitis is the most frequent extra-articular manifestation, occurring in 25 to 30 percent of patients. The uveitis usually is acute, unilateral, and recurrent. Eye pain, red eye, blurry vision, photophobia, and increased lacrimation are presenting signs. Cardiac manifestations include aortic and mitral root dilatation, with regurgitation and conduction defects. Fibrosis may develop in the upper lobes of the lungs in patients with longstanding disease. [6] Level 5

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Most Common differential diagnosis[2]

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Psoriasis

- Reiter's syndrome

- Fracture

- Osteoarthritis

- Inflammatory bowel disease[7] : Ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease

- Psoriatic spondylitis [7]

- Scheuermann’s disease/|Scheuermann's Kyphosis [7]

- Paget’s disease [7] Level 5

Differential Diagnosis of Ankylosing Spondylitis and Thoracic Spinal Stenosis[7]

| Ankylosing Spondylitis | Thoracic Spinal Stenosis | |

|---|---|---|

| History | Morning stiffness Intermittent aching pain Male predominance Sharp pain Bilateral sacroiliac pain may refer to posterior thigh |

Intermittent aching pain Pain may refer to both legs with walking |

| Active movements | Restricted | May be normal |

| Passive movements | Restricted | May be normal |

| Resisted isometric movements |

Normal | Normal |

| Special tests | None | Bicycle test of van Gelderen may be positive Stoop test may be positive |

| Reflexes | Normal | May be affected in long standing cases |

| Sensory deficit | None | Usually temporary |

| Diagnostic imaging | Plain films are diagnostic | Computed tomography scans are diagnostic |

In the early stages of ankylosing spondylitis, the changes in the sacroiliac joint are similar to that of rheumatoid arthritis, however the changes are almost always bilateral and symmetrical. This fact allows ankylosing spondylitis to be distinguished from psoriasis, Reiter's syndrome, and infection. Changes at the sacroiliac joint occur throughout the joint, but are predominantly found on the iliac side.

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

AS can be diagnosed by the modified New York criteria, the patient must have radiographic evidence of sacroiliitis and one of the following: (1) restriction of the lumbar spine motion in both the sagittal and frontal planes, (2) restriction of chest expansion (usually < 2.5 cm) (3) a history of back pain includes onset at <40 year, gradual onset, morning stiffness, improvement with activity, and duration >3 months.[8]

Imaging tests

- X-rays. Radiographic findsing of symmetric, bilateral sacroiliitis include blurring of joint margins, extaarticular sclerosis, erosion, and joint space narrowing. As bony tissue bridges the vertebral bodies and posterior arches, the lumbar and thoracic spine creates a “bamboo spine” image on radiographs.[2]

- Computerized tomography (CT). CT scans combine X-ray views taken from many different angles into a cross-sectional image of internal structures. CT scans provide more detail, and more radiation exposure, than do plain X-rays.[2]

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Intraarticular inflammation, early cartilage changes and underlying bone marrow edema and osteitis can be seen using an MRI technique called short tau inversion recovery (STIR). Using radio waves and a strong magnetic field, MRI scans are better at visualizing soft tissues such as cartilage. [2]

- Lab tests. There is no laboratory test to diagnose ankylosing spondylitis but the HLA-B27 gene has been found to be present in about 90 to 95 percent of affected white patients in central Europe and North America [2] Level 5. The presence of the HLA-B27 antigen is a useful adjunct to the diagnosis, but cannot be diagnostic alone.[2]

Four out of five positive responses to the following questions may help with the determining of AS:

- Did the back discomfort begin before age 40

- Did the discomfort begin slowly

- Has the discomfort persisted for 3 months

- Was morning stiffness a problem

- Did the discomfort improve with exercise

Specificity= 0.82, Sensitivity =0.23

LR for four out of five positive responses = 1.3[6]

Chronic low back pain (LBP), the leading symptom of ankylosing spondylitis (AS) and undifferentiated axial spondyloarthritis (SpA), precedes the development of radiographic sacroiliitis, sometimes by many years. [4] Level 4

It is also noted that patients with ankylosing spondylitis (AS) have an increased risk of bone loss and vertebral fractures. [7] Level 3B

In summary, the diagnostic procedures for Ankylosing Spondylitis include:

- Imaging tests such as X-ray and CT scans

- HLA B27 gene presence (genetical factor)

- Blood samples with focus on CRP levels

- BASDAI, BASMI and BASFI [9] Level 1B

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

Modified Health Assessment Questionnaire (MHAQ)

Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) [9] Level 1B

ASQoL [9] Level 1B

Assessment of the duration of morning stiffness using “0–10 cm” horizontal visual analogue scale, as well as duration of morning stiffness in minutes. [9] Level 1B

Self-report joint tenderness: this is carried out on a joint diagram with the joint names written beside it as a guide and the patient is asked to tick the box matching the painful joint(s) [30] Level 1B

Self-reported soft tissue tenderness (enthesitis): this is carried out on a skeleton model and the patient is asked to highlight the places he feels pain. [9] Level 1B

Examination[edit | edit source]

Physical examination of the spine involves the cervical, thoracic and lumbar region.

Cervical involvement often occurs late. The stooping of the neck can be measured by the occiput-to-wall distance. The patient stands with the back and heels against the wall and the distance between the back of the head and the wall is measured. Video occiput-to-wall test

The thoracic spine can be tested by the chest expansion. It is measured at the fourth intercostal space and in women just below the breasts. The patient should be asked to force a maximal inspiration and expiration and the difference in chest expansion is measured. A chest expansion of less than 5 cm is suspicious and < 2.5 cm is abnormal and raises the possibility of AS unless there is another reason for it, like emphysema. The normal thoracic kyphosis of the dorsal spine is accentuated. The costovertebral, costotransverse and manubriosternal joints should be palpated to detect inflammation which causes pain on palpitation.

The lumbar spine can be tested by the Schober’s test. This is performed by making a mark between the posterior superior iliac spines at the 5th lumbar spinous process. A second mark is placed 10 cm above the first one and the patient is asked to bend forward with extended knees. The distance between the two marks increases from 10 to at least 15 cm in normal people, but only to 13 or less in case of AS. [1] Level 5

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

According to Braun et al [10] (2010, Level of Evidence 5) the overarching principles of the management of patients with AS are:

- Requirement of a multidisciplinary treatment coordinated by the rheumatologist.

- The primary goal is to maximise long term health-related quality of life. Therefore it is important to control symptoms and inflammation, prevent progressive structural damage, preserve/normalise function and social participation.

- The treatment should aim at the best care and requisites a shared decision between the patient and the rheumatologist.

- A combination of non-pharmacological and pharmacological treatment modalities is required.

1. General treatment

The treatment of patients with AS should be individualised according to:

- The present manifestations of the disease (peripheral, axial, entheseal, extra-articular symptoms and signs).

- The level of current symptoms, prognostic indicators and clinical findings.

- The general clinical status (gender, age, comorbidity, psychosocial factors, concomitant medications).

2. Disease monitoring

The disease monitoring of patients with AS should include:

- Patient history (eg, questionnaires)

- Laboratory tests

- Clinical parameters

- Imaging

- The frequency of monitoring should be individualised depending on: course of symptoms, treatment and severity

3. Non-pharmacological treatment

- Patient education and regular exercise form the cornerstone of non-pharmacological treatment of patients with AS.

- Home exercises are effective. However, physical therapy with supervised exercises, land or water based, individually or in a group, should be preferred as these are more effective than home exercises.

- Self-help groups and patient associations may be useful.

4. Extra-articular manifestations and comorbidities

- Psoriasis, uveitis and IBD are some of the frequently observed extra-articular manifestations. They should be managed in collaboration with the respective specialists.

- Rheumatologists should be aware of the increased risk of cardiovascular disease and osteoporosis in patients with AS.

5. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

- For AS patients with pain and stiffness, NSAID, including Coxibs, are recommended as first-line drug treatment.

- For patients with persistently active, symptomatic disease, continuous treatment with NSAID is preferred.

6. Analgesics: after previously recommended treatments have failed, are contraindicated, and/or poorly tolerated.

7. Anti-TNF therapy

- According to the ASAS recommendations, anti-TNF therapy should be given to patients with persistently high disease activity despite conventional treatments.

- Shifting to a second TNF blocker may be beneficial, especially in patients with loss of response.

- No evidence exists to support the use of biological agents other than TNF inhibitors in AS.

8. Surgery

- In patients with refractory pain or disability and radiographic evidence of structural damage, independent of age, total hip arthroplasty should be considered.

- In patients with severe disabling deformity, spinal corrective osteotomy may be considered.

- A spinal surgeon should be consulted in patients with AS and an acute vertebral fracture.

9. Changes in the disease course: Other causes than inflammation (eg. spinal fracture) should be considered if a significant change in the course of the disease occurs and appropriate evaluation, including imaging, should be performed.

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

Rehabilitation should be patient-centred. It should also enable the patient to achieve independence, social integration and improve quality of life. The aim of physical therapy and rehabilitation in AS is to:

- Reduce discomfort and pain;

- Maintain or improve endurance and muscular strength;

- Maintain or improve mobility, flexibility and balance;

- Maintain or improve physical fitness and social participation;

- Prevent spinal curve abnormalities as well as spinal and joint deformities. [2] Level 5

A multimodal physical therapy program including aerobic, stretching, education and pulmonary exercises in conjunction with routine medical management has been shown to produce greater improvements in spinal mobility, work capacity, and chest expansion compared with medical care alone.[2] Evidence showed that aerobic training improved walking distance and aerobic capacity in patients with AS. However, Aerobic training did not provide additional benefits in functional capacity, mobility, disease activity, quality of life, and lipid levels when compared with stretching exercises alone (Jennings et al, 2015). Evidence also showed that passive stretching resulted in a significant increase in the range of movement (ROM) of the hip joints in all directions except flexion during the physiotherapy course. This increase in ROM could be maintained by patients who performed the stretching exercises on a regular basis [3] Level 1B. Since the severity of AS is very different among individuals, there is no specific exercise program that showed the greatest improvements. Some studies showed that a 50 minute, three times a week multimodal exercise program showed significant improvements after 3 months in chest wall excursion, chin to chest distance, occiput to wall distance, and the modified Schober flexion test.[2]

However, according to Ozgocmen et al. [2] (Level 5) some key recommendations can be formulated for patients with AS:

- Physiotherapy and rehabilitation should start as soon as AS is diagnosed.

- Physiotherapy should be planned according to the patients’ needs, expectations and clinical status, as well as be commenced and monitored properly.

- Physiotherapy should be performed as an inpatient or outpatient program in all patients, regardless of disease stage, and should be carried out in obedience with general rules and contraindications.

- Lifelong regular exercises are the anchor of treatment. A combined regime of inpatient spa-exercise therapy followed by group physiotherapy is recommended for the highest benefit, and group physiotherapy is also favored to home exercises [2] Level 5 [5]Level 5

- As mentioned before, the conventional protocols of physiotherapy including stretching, flexibility and breathing exercises, as well as pool and land-based exercises and accompanying recreational activities are recommended.

- Physiotherapy modalities should be used as complementary therapies based on the experience gained from their use in other musculoskeletal disorders [2] Level 5

EXERCISE TRAINING PROGRAM

A few recommended exercises for an individual with AS (Masiero et al, 2011) [4] Level 1B:

- Respiratory exercises (10min)

2 Series of 10 repetitions each:

1. Chest expansion

2. Deep breathing

3. Thoracic breathless

4. Expiratory breathless

5. Diaphragmatic breathing exercises and abdominal control

6. Scapular girdle muscle exercises ( i.e., shoulder elevation in combination with breathless)

- Exercises to mobilize the vertebrae and limbs (15 min)

2 series of 10 repetitions each per mobilization. Performed lying and/or seated and/or standing and/or on all fours or walking pain-free. Spinal exercises can also be combined with respiratory exercises (i.e., deep breathing or expiratory breathless)

1. Cervical side: lateral flexion and rotation (right and left), extension

2. Thoraco-lumbar side: lateral-flexion, extension, rotation

3. Shoulder and upper limb side: ab/adduction, flexion, elevation, and circumduction

4. Coxofemoral, knee and ankle side: ab/adduction, rotation and flexion-extension

- Balancing and proprioceptive exercises (10 min)

2 series of 10 repetitions: standing and walking

- Postural exercises and spinal and limb muscle stretching and strengthening (15min)

2 repetitions of an average of about 30/40 seconds each for stretching. All exercises could be performed both lying and seated or on all fours or in a standing position with active and passive mobility, pain-free

1. Stretching exercises for the posterior muscle chain of the spine (thoraco-lumbar and all erector spine group, etc.) and anterior muscle chain of the spine (superior and inferior abdominal etc.)

2. Stretching exercises for the anterior girdle muscle chain (psoas, hamstring etc.) and posterior pelvic girdle muscle chain

3. Stretching of posterior and anterior muscles of lower limbs - Endurance training (10 min)

Walking, treadmill, cycling or swimming for a progressive duration on the basis of the patient’s functional capacity (low speed, without resistance). - Posture education can be a very important component to the patient to maintain an erect posture as well. [2]

- Aquatic therapy can be an excellent option for most patients to provide low impact extension and rotation principles.[2]

- Pain education can be a very important benefit to the patient as well (Masiero et al, 2011). [4] Level 1B

Exercises that should be avoided include high impact and flexion exercises. Over exercising can be potentially harmful and could exacerbate the inflammatory process.[2]

MANUAL THERAPY

Some have advocated the efficacy and use of gentle non-thrust manipulation in the spine.

Eight weeks of self- and manual mobilization improved chest expansion, posture and spine mobility in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. The physiotherapeutic intervention consisted initially of warming up the soft tissue of the back muscles (with vibrations via a vibrator) and gentle mobility exercises. This was followed by both active angular and passive mobility exercises in the physiological directions of the joints in the spinal column and in the chest wall in three directions of motion (flexion/ extension, lateral flexion and rotation) and in different starting positions (lying face down, sideways, on the back and in a sitting position). Passive mobility exercises consisted of general, angular movements and specific, translatory movements. Stretching of tight muscles was done using the contracting–relaxing method. Soft tissue treatment (manual massage) of the neck was performed followed by relaxation exercises in a standing position and resting for some minutes lying on the treatment bench [5]

Key Research[edit | edit source]

Dagfinrud, H., Hagen, K. B., & Kvien, T. K. (2008). Physiotherapy interventions for ankylosing spondylitis. The Cochrane Library.

Chang, W. D., Tsou, Y. A., & Lee, C. L. (2016). Comparison between specific exercises and physical therapy for managing patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF CLINICAL AND EXPERIMENTAL MEDICINE, 9(9), 17028-17039.

Liang, H., Zhang, H., Ji, H., & Wang, C. (2015). Effects of home-based exercise intervention on health-related quality of life for patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a meta-analysis. Clinical rheumatology, 34(10), 1737-1744.

O’Dwyer, T., O’Shea, F., & Wilson, F. (2014). Exercise therapy for spondyloarthritis: a systematic review. Rheumatology international, 34(7), 887-902.

Martins, N. A., Furtado, G. E., Campos, M. J., Ferreira, J. P., Leitão, J. C., & Filaire, E. (2014). Exercise and ankylosing spondylitis with New York modified criteria: a systematic review of controlled trials with meta-analysis. Acta Reumatológica Portuguesa, 39(4).

Nghiem, F. T., & Donohue, J. P. (2008). Rehabilitation in ankylosing spondylitis. Current opinion in rheumatology, 20(2), 203-207.

Fernandez-de-las-Penas, C., Alonso-Blanco, C., Aguila-Maturana, A. M., Isabel-de-la-Llave-Rincon, A., Molero-Sanchez, A., & Miangolarra-Page, J. C. (2006). Exercise and ankylosing spondylitis—which exercises are appropriate? A critical review. Critical Reviews™ in Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine, 18(1).

Stasinopoulos, D., Papadopoulos, K., Lamnisos, D., & Stergioulas, A. (2016). LLLT for the management of patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Lasers in medical science, 31(3), 459-469.

Karamanlioğlu, D. Ş., Aktas, I., Ozkan, F. U., Kaysin, M., & Girgin, N. (2016). Effectiveness of ultrasound treatment applied with exercise therapy on patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Rheumatology international, 36(5), 653-661.

Jennings, F., Oliveira, H. A., de Souza, M. C., da Graça Cruz, V., & Natour, J. (2015). Effects of Aerobic Training in Patients with Ankylosing Spondylitis. The Journal of rheumatology, 42(12), 2347-2353.

Niedermann, K., Sidelnikov, E., Muggli, C., et al. (2013) Effect of cardiovascular training on fitness and perceived disease activity in people with ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis care & research, 65(11), 1844-1852.

Resources[edit | edit source]

Fig 1: http://www.physio-pedia.com/images/f/fe/Spondy_1.png

Table 1: Source 22 (Kataria et al., 2004)

Fig 2: http://www.physio-pedia.com/images/b/b0/Spondy4.jpg

Fig 3: http://www.physio-pedia.com/images/c/c5/Spine-t_ankylosing_spondylitis.jpg

Video occiput-to-wall test: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rOR70O_zTdA

Clinical Bottom Line[edit | edit source]

Spondyloarthropathy is a group of multisystem inflammatory disorders affecting various joints including the spine, peripheral joints and periarticular structures. They are associated with extra-articular manifestations (for example a fever). The majority are HLA B27 positive (serological test) and Rheumatoid Factor (RF) negative.

There are 4 major seronegative spondyloarthropathies:

- Ankylosing Spondylitis (AS): is the prototype and effects more men than women

- Reiter’s Syndrome

- Psoriatic Arthritis

- Arthritis of Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Sacroiliitis is a common manifestation in all of these disorders.

Although a triggering infection and immune mechanisms are thought to underlie most of the spondyloarthopathies, their pathogenesis remains obscure.

Physical examination of the spine involves the cervical, thoracic and lumbar region. The physician may ask the patient to bend the back in different ways, check the chest circumference and also may search for pain points by pressing on different portions of the pelvis. In doubt the physician effects different diagnostic procedures such as X-ray imaging, HLA B27 presence, CRP levels in blood samples.

The treatment for AS can be divided into:

- Medication

- Non steroid anti inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

- Anti – TNF therapy

Physiotherapy is the best known non surgical therapeutic way of treating AS improving flexibility and physical strength. Surgery is only recommended in patients with chronic cases Most cases can be treated without surgery.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 Goodman C, Snyder T. Differential Diagnosis for Physical Therapists: Screening for Referral. St. Louis, MO: Saunders Elsevier: 2007. 539

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 2.16 2.17 2.18 2.19 2.20 2.21 2.22 2.23 2.24 2.25 Kataria R.K. et al., Spondyloarthropathies. Am Fam Physician, 2004, 69 (12):2853-2860 Level of Evidence 5

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Benjamin M. and McGonagle D., The anatomical basis for disease localization in seronegative spondyloarthropathy at entheses and related sites. J. Anat., 2001. Level of Evidence 5

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Hermann K.G.A., Bollow M., Magnetic Resonance Imaging of Sacroiliitis in Patients with Spondyloarthritis: Correlation with Anatomy and Histology. Fortschr Röntgenstr, 2014, 186:3, 230-237 Level of Evidence 1B

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 Beers MH, et. al. eds. The Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy. 18th ed. Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck Research Laboratories; 2006.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Sieper J., et al. Ankylosing spondylitis: an overview. Ann Rheum Dis 2002;61, 8-18. Level of Evidence 5

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 Jarvik, J. G., & Deyo, R. A. (2002). Diagnostic evaluation of low back pain with emphasis on imaging. Annals of internal medicine, 137(7), 586-597. Level of Evidence 3B

- ↑ Beers MH, ed. The Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy, 18th edition. Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck and CO; 2006

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 El Miedany Y. Towards a multidimensional patient reported outcome measures assessment: Development and validation of a questionnaire for patients with ankylosing spondylitis/spondyloarthritis. Elsevier, 2010, Volume 77, Issue 6 Level of Evidence 1B

- ↑ Braun, J. von, Van Den Berg, R., Baraliakos, X., et al. 2010 update of the ASAS/EULAR recommendations for the management of ankylosing spondylitis. Annals of the rheumatic diseases, 2011, vol. 70, no 6, p. 896-904. Level of Evidence 5