Psychosocial Considerations in Patellofemoral Pain: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 29: | Line 29: | ||

=== Loss, Confusion and Fear-Avoidance Associated with Patellofemoral Pain === | === Loss, Confusion and Fear-Avoidance Associated with Patellofemoral Pain === | ||

Smith et al.<ref name=":7" /> conducted a qualitative study on the experience of living with patellofemoral pain and the associated sense of loss, confusion and fear-avoidance. The full article is available here: [https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/bmjopen/8/1/e018624.full.pdf The experience of living with patellofemoral pain-loss, confusion and fear-avoidance: a UK qualitative study]. | |||

Many patients with patellofemoral pain reported experiencing a '''loss''' of identity and a decrease in their social interactions. For example, if an individual has patellofemoral pain which limits them from participating in their sport of choice, we need to remember that it is not only the activity / sport they are suddenly unable to participate in. They may also lose the sense of well-being and social interaction normally offered by the sport. [[File:Pain_Experience_-_COR-Kinetic_Image.jpg|alt=|thumb|Figure 2. Pain experience.]] | |||

Thus, patellofemoral pain can have wide ranging effects and an individual's beliefs about their knee pain can cause them to make significant lifestyle adaptations.<ref name=":6" /> Some individuals might feel compelled to change their career aspirations<ref name=":7" /> and housing choices.<ref name=":6" /> | |||

Patients can battle with their understanding of the causes of their knee pain, especially when it is of insidious onset. Unlike a traumatic injury, knee pain of insidious onset is not marked by a specific event to which the pain can be attributed. This can lead to the '''confusion''', '''uncertainty''' and the incorrect assumption that exercise or activity worsens their pain.<ref name=":7">Smith BE, Moffatt F, Hendrick P, Bateman M, Rathleff MS, Selfe J, et al. [https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/bmjopen/8/1/e018624.full.pdf The experience of living with patellofemoral pain-loss, confusion and fear-avoidance: a UK qualitative study]. BMJ Open. 2018;8(1):e018624. </ref> When a physiotherapist then prescribes exercise-based treatment, a patient might be hesitant and / or non-compliant due to their belief that exercise actually caused their pain. Thus, the patient should be educated on the effects of load, repetitive volume, warm up, cool down, footwear, and the many other facets that are vital to understanding exercise.<ref name=":6" /> | |||

When study participants discussed treatments or '''coping strategies''', many focused on the idea of rest and postural adjustments, such as avoiding flexion in sitting. They also felt that passive treatments, such as pain medication and knee supports, would be of benefit.<ref name=":7" /> While these might help the pain temporarily, they will not be beneficial to the patient in the long term.<ref name=":6" /> | |||

=== Psychologically-Informed Treatments === | === Psychologically-Informed Treatments === | ||

A study by Selhorst et al.<ref name=":4">Selhorst M, Fernandez-Fernandez A, Schmitt L, Hoehn J. [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33838141/ Effect of a Psychologically Informed Intervention to Treat Adolescents With Patellofemoral Pain: A Randomized Controlled Trial.] Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2021 Jul 1;102(7):1267-73.</ref> offers insight into how psychologically-informed treatments may be beneficial for adolescents with patellofemoral pain. The study group were shown an educational video which focused on pain-related fear and pain catastrophising. | A study by Selhorst et al.<ref name=":4">Selhorst M, Fernandez-Fernandez A, Schmitt L, Hoehn J. [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33838141/ Effect of a Psychologically Informed Intervention to Treat Adolescents With Patellofemoral Pain: A Randomized Controlled Trial.] Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2021 Jul 1;102(7):1267-73.</ref> offers insight into how psychologically-informed treatments may be beneficial for adolescents with patellofemoral pain. The study group were shown an educational video which focused on pain-related fear and pain catastrophising. Compared to the control, the study group showed a reduction in [[kinesiophobia]], catastrophisation and pain scores, immediately and at two weeks. This highlights the significance of education in patellofemoral pain. | ||

=== Sleep === | === Sleep === | ||

In patients with patellofemoral pain, it is also important to consider their [[Sleep Deprivation and Sleep Disorders|sleep]] patterns, including the quantity / duration of sleep as well as the quality of sleep. When conducting an assessment we should consider asking questions such as, "how many times do you wake up in the night? How long does it take to get to sleep?"<ref name=":6" /> | |||

=== Mindfulness === | === Mindfulness === | ||

Research carried out by Bagheri et al.<ref name=":3">Bagheri S, Naderi A, Mirali S, Calmeiro L, Brewer BW. [https://meridian.allenpress.com/jat/article/56/8/902/448491/Adding-Mindfulness-Practice-to-Exercise-Therapy Adding mindfulness practice to exercise therapy for female recreational runners with patellofemoral pain: A randomized controlled trial.] Journal of Athletic Training. 2021 Aug 1;56(8):902-11.</ref> showed that when mindfulness was included with physical treatments, there was a greater improvement in pain reduction, catastrophisation and kinesiophobia in female runners with patellofemoral pain. Mindfulness is aimed at increasing awareness of thoughts, sensations and emotions, with an attitude of acceptance, curiosity and openness.<ref name=":3" /> The focus of mindfulness is to reduce stress, take control of the situation, stay in control, and not be overly alarmed by it. | |||

Rehabilitation therapists often focus on reducing pain. But if a patient is discharged from treatment with incorrect beliefs about their knee pain, they could continue fear avoidance behaviours and experience anxiety while playing sport.<ref>Smith IV BN. [https://digitalcommons.memphis.edu/etd/1672/ Resiliency, Generalized Self-Efficacy and Mindfulness as Moderators of the Relationship between Stress and both Life Satisfaction and Depression among College Students: An Investigation of the Resilience Process]. 2017.</ref> Thus, it is important to address the psychosocial factors, as well as the physical ones. | |||

==== Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia ==== | ==== Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia ==== | ||

The | The Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia (TSK) can be a useful measure in patellofemoral pain.<ref name=":6" /> The original TSK was first developed in 1990 by R. Miller, S. Kopri, and D. Todd. It is a 17 item self-report questionnaire which evaluates fear of movement, fear of physical activity, and fear avoidance. It was first developed to distinguish between "non-excessive fear and phobia"<ref name=":8" /> in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain, specifically chronic low back pain. It is now widely used for different parts of the body.<ref name=":8">Hudes K. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3154068/ The Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia and neck pain, disability and range of motion: a narrative review of the literature.] The Journal of the Canadian Chiropractic Association. 2011 Sep;55(3):222.</ref> | ||

'''Links:''' | '''Links:''' | ||

| Line 57: | Line 59: | ||

* [https://www.mdapp.co/tampa-scale-for-kinesiophobia-tsk-calculator-465/#:~:text=all%2017%20items.-,TSK%20scores%20range%20from%2017%20to%2068%2C%20where%20scores%20of,below%20this%20value%20considered%20low. MDApp, Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia] | * [https://www.mdapp.co/tampa-scale-for-kinesiophobia-tsk-calculator-465/#:~:text=all%2017%20items.-,TSK%20scores%20range%20from%2017%20to%2068%2C%20where%20scores%20of,below%20this%20value%20considered%20low. MDApp, Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia] | ||

== Psychosocial Factors | == Addressing Psychosocial Factors == | ||

===== Psychosocial Factors ===== | ===== Psychosocial Factors ===== | ||

| Line 75: | Line 77: | ||

|- | |- | ||

|Duration of symptoms? | |Duration of symptoms? | ||

|The longer the duration the more likely there will be central pain changes | |The longer the duration, the more likely there will be [[Central Sensitisation|central pain changes]] | ||

|Assess for central changes | |Assess for central changes | ||

|- | |- | ||

|Alteration in sleep quality? | |Alteration in sleep quality? | ||

|Serotonin (natural painkiller) production suppressed with poor sleep | |Serotonin (natural painkiller) production suppressed with poor sleep | ||

|Recommend re-establishing routine | |Recommend re-establishing routine; | ||

Non-painful exercise; | |||

Decrease anxiety through education | Decrease anxiety through education | ||

|- | |- | ||

|Change in exercise profile? | |Change in exercise profile? | ||

|Can affect sleep, mood, self-esteem, social interactions and conditioning | |Can affect sleep, mood, self-esteem, social interactions and conditioning | ||

|Consider exercise programmes for non-painful body parts initially | |Consider exercise programmes for non-painful body parts initially; | ||

Education to minimise fear-avoidance | Education to minimise fear-avoidance | ||

|- | |- | ||

|Can they tolerate the sense of clothing on their knee, eg skinny jeans/tights? | |Can they tolerate the sense of clothing on their knee, eg skinny jeans/tights? | ||

|Some patients cannot bear the feeling of material on their knee | |Some patients cannot bear the feeling of material on their knee - this is highly suggestive of non-mechanical pain | ||

|Graduated exposure | |Graduated exposure; | ||

May need medical management to de-sensitise | |||

|} | |} | ||

Revision as of 02:48, 31 August 2022

Top Contributors - Carin Hunter, Jess Bell, Ewa Jaraczewska, Kim Jackson and Wanda van Niekerk

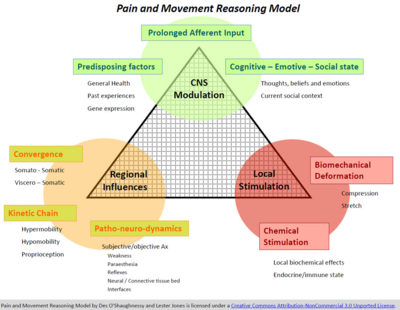

The Pain and Movement Reasoning Model[edit | edit source]

The Pain and Movement Reasoning Model is designed to improve clinical reasoning.[1] It aims to "capture the complexity of the human pain experience by integrating these multiple dimensions into a decision making process."[2] As is shown in Figure 1, this model includes three categories.

- Local stimulation[2][3]

- Biomechanical stimulation

- Chemical stimulation

- Regional influences[2][3]

- Kinetic chain

- Patho-neuro-dynamics

- Convergence

- Central nervous system modulation[2][3]

- Prolonged afferent input

- Predisposing factors

- Cognitive - emotive - social state

Clinicians use the model to identify the most important category for each patient. Once identified, it can help to direct treatment. The model also enables clinicians to identify when there are changes in presentation and, thus, if a new / different treatment approach should be adopted.[2]

While the pain and movement reasoning model was not designed for patellofemoral pain, the theory can be effectively applied for patients with this condition.[4] Local stimulation in patellofemoral pain consists of factors such as bone oedema, fat pad swelling, effusion, retinacular ischaemic changes, bone bruising, or anything local at the knee. Regional influences include excessively pronating feet, an anteverted femoral neck or poor hip abduction control. There is not, however, much available research to show the role played by the central nervous system.

Psychosocial Factors and Patellofemoral Pain[edit | edit source]

There is a general lack in research on the impact of psychosocial factors on patellofemoral pain, but they should not be ignored.[4]

Depression and Anxiety[edit | edit source]

Research by Wride and Bannigan[5] highlights important correlations between anxiety and depression and patellofemoral pain:

- The prevalence of anxiety and / or depression is higher in the patellofemoral population than the normal population[5]

- The prevalence of anxiety and / or depression is higher in young females[5]

- Individuals with high anxiety scores were more likely to be female[5]

- The rate of patellofemoral pain is higher in females[6]

Loss, Confusion and Fear-Avoidance Associated with Patellofemoral Pain[edit | edit source]

Smith et al.[7] conducted a qualitative study on the experience of living with patellofemoral pain and the associated sense of loss, confusion and fear-avoidance. The full article is available here: The experience of living with patellofemoral pain-loss, confusion and fear-avoidance: a UK qualitative study.

Many patients with patellofemoral pain reported experiencing a loss of identity and a decrease in their social interactions. For example, if an individual has patellofemoral pain which limits them from participating in their sport of choice, we need to remember that it is not only the activity / sport they are suddenly unable to participate in. They may also lose the sense of well-being and social interaction normally offered by the sport.

Thus, patellofemoral pain can have wide ranging effects and an individual's beliefs about their knee pain can cause them to make significant lifestyle adaptations.[4] Some individuals might feel compelled to change their career aspirations[7] and housing choices.[4]

Patients can battle with their understanding of the causes of their knee pain, especially when it is of insidious onset. Unlike a traumatic injury, knee pain of insidious onset is not marked by a specific event to which the pain can be attributed. This can lead to the confusion, uncertainty and the incorrect assumption that exercise or activity worsens their pain.[7] When a physiotherapist then prescribes exercise-based treatment, a patient might be hesitant and / or non-compliant due to their belief that exercise actually caused their pain. Thus, the patient should be educated on the effects of load, repetitive volume, warm up, cool down, footwear, and the many other facets that are vital to understanding exercise.[4]

When study participants discussed treatments or coping strategies, many focused on the idea of rest and postural adjustments, such as avoiding flexion in sitting. They also felt that passive treatments, such as pain medication and knee supports, would be of benefit.[7] While these might help the pain temporarily, they will not be beneficial to the patient in the long term.[4]

Psychologically-Informed Treatments[edit | edit source]

A study by Selhorst et al.[8] offers insight into how psychologically-informed treatments may be beneficial for adolescents with patellofemoral pain. The study group were shown an educational video which focused on pain-related fear and pain catastrophising. Compared to the control, the study group showed a reduction in kinesiophobia, catastrophisation and pain scores, immediately and at two weeks. This highlights the significance of education in patellofemoral pain.

Sleep[edit | edit source]

In patients with patellofemoral pain, it is also important to consider their sleep patterns, including the quantity / duration of sleep as well as the quality of sleep. When conducting an assessment we should consider asking questions such as, "how many times do you wake up in the night? How long does it take to get to sleep?"[4]

Mindfulness[edit | edit source]

Research carried out by Bagheri et al.[9] showed that when mindfulness was included with physical treatments, there was a greater improvement in pain reduction, catastrophisation and kinesiophobia in female runners with patellofemoral pain. Mindfulness is aimed at increasing awareness of thoughts, sensations and emotions, with an attitude of acceptance, curiosity and openness.[9] The focus of mindfulness is to reduce stress, take control of the situation, stay in control, and not be overly alarmed by it.

Rehabilitation therapists often focus on reducing pain. But if a patient is discharged from treatment with incorrect beliefs about their knee pain, they could continue fear avoidance behaviours and experience anxiety while playing sport.[10] Thus, it is important to address the psychosocial factors, as well as the physical ones.

Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia[edit | edit source]

The Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia (TSK) can be a useful measure in patellofemoral pain.[4] The original TSK was first developed in 1990 by R. Miller, S. Kopri, and D. Todd. It is a 17 item self-report questionnaire which evaluates fear of movement, fear of physical activity, and fear avoidance. It was first developed to distinguish between "non-excessive fear and phobia"[11] in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain, specifically chronic low back pain. It is now widely used for different parts of the body.[11]

Links:

- Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia

- Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia (TSK) pdf

- MDApp, Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia

Addressing Psychosocial Factors[edit | edit source]

Psychosocial Factors[edit | edit source]

- Depressive symptoms[12]

- Higher levels of anxiety[12]

- Fear avoidance

- Lifestyle changes

- Kinesiophobia[8][9]

- Catastrophisation[8][9]

Questions to ask[edit | edit source]

| Question | Reason | Treatment Implication |

| Duration of symptoms? | The longer the duration, the more likely there will be central pain changes | Assess for central changes |

| Alteration in sleep quality? | Serotonin (natural painkiller) production suppressed with poor sleep | Recommend re-establishing routine;

Non-painful exercise; Decrease anxiety through education |

| Change in exercise profile? | Can affect sleep, mood, self-esteem, social interactions and conditioning | Consider exercise programmes for non-painful body parts initially;

Education to minimise fear-avoidance |

| Can they tolerate the sense of clothing on their knee, eg skinny jeans/tights? | Some patients cannot bear the feeling of material on their knee - this is highly suggestive of non-mechanical pain | Graduated exposure;

May need medical management to de-sensitise |

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Jones LE, Heng H, Heywood S, Kent S, Amir LH. The suitability and utility of the pain and movement reasoning model for physiotherapy: A qualitative study. Physiother Theory Pract. 2021:1-14.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Jones LE, O'Shaughnessy DF. The pain and movement reasoning model: introduction to a simple tool for integrated pain assessment. Manual therapy. 2014 Jun 1;19(3):270-6.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 O’Shaughnessy D, Jones LE. Making sense of pain in sports physiotherapy: applying the Pain and Movement Reasoning Model. A Comprehensive Guide to Sports Physiology and Injury Management: an interdisciplinary approach. 2020 Nov 13:107.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 Robertson C. Psychosocial Considerations in Patellofemoral Pain Course. Plus. 2022.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Wride J, Bannigan K. Investigating the prevalence of anxiety and depression in people living with patellofemoral pain in the UK: the Dep-Pf Study. Scandinavian Journal of Pain. 2019 Apr 1;19(2):375-82.

- ↑ Boling M, Padua D, Marshall S, Guskiewicz K, Pyne S, Beutler A. Gender differences in the incidence and prevalence of patellofemoral pain syndrome. Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports. 2010 Oct;20(5):725-30.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Smith BE, Moffatt F, Hendrick P, Bateman M, Rathleff MS, Selfe J, et al. The experience of living with patellofemoral pain-loss, confusion and fear-avoidance: a UK qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2018;8(1):e018624.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Selhorst M, Fernandez-Fernandez A, Schmitt L, Hoehn J. Effect of a Psychologically Informed Intervention to Treat Adolescents With Patellofemoral Pain: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2021 Jul 1;102(7):1267-73.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Bagheri S, Naderi A, Mirali S, Calmeiro L, Brewer BW. Adding mindfulness practice to exercise therapy for female recreational runners with patellofemoral pain: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Athletic Training. 2021 Aug 1;56(8):902-11.

- ↑ Smith IV BN. Resiliency, Generalized Self-Efficacy and Mindfulness as Moderators of the Relationship between Stress and both Life Satisfaction and Depression among College Students: An Investigation of the Resilience Process. 2017.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Hudes K. The Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia and neck pain, disability and range of motion: a narrative review of the literature. The Journal of the Canadian Chiropractic Association. 2011 Sep;55(3):222.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Alabajos-Cea A, Herrero-Manley L, Suso-Martí L, Alonso-Pérez-Barquero J, Viosca-Herrero E. Are psychosocial factors determinant in the pain and social participation of patients with early knee osteoarthritis? A Cross-Sectional Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021 Apr 26;18(9):4575.