Inflammaging: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 39: | Line 39: | ||

<references /> | <references /> | ||

[[Category:Older People/Geriatrics]] | |||

[[Category:Older People/Geriatrics - Conditions]] | |||

[[Category:Physiology]] | |||

Revision as of 02:52, 30 July 2022

Original Editor - Lucinda hampton

Top Contributors - Lucinda hampton and Tolulope Adeniji

Introduction[edit | edit source]

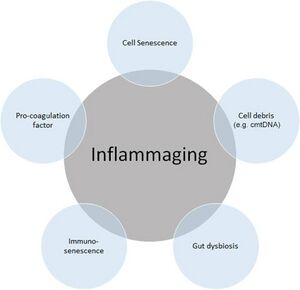

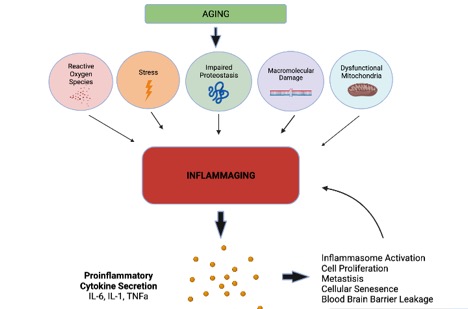

Old age is typified by an atypical low-grade, chronic, and "sterile" inflammatory state, know as inflammaging, ie. an age-related increase in systemic chronic inflammatory status. Several contributory factors to inflammaging include accumulated oxidative stress, changes within the inflammatory cytokine network, and cellular senescence with advancing age. These changes are associated with a loss of physical and immune resilience, amplifying the risk of being malnourished and frail and significantly contributing to the pathogenesis of many age-related diseases and to the progression of the ageing process.[1][2]

The salient points of inflammaging are:

- Immunosenescence, an age associated process that impairs the immune function, is the main driver of inflammaging. With immunosenescence thymic involution occurs and reduces the pool of naïve T cells and amplifies the oligo-clonal expansion of memory T cells. These events will cause a reduced immune repertoire diversity, leading to reduced ability to fight infections and increased cancer incidence[3]

- With aging, the accumulated exposure to free radicals produced by environmental factors including cigarette smoke, dietary factors, and ionizing radiations generates “oxidative stress” in the older person. This causes oxidative protein damage and harmful DNA changes which contributes to, for example, cancer progression through upregulating inflammatory responses.

- Ageing in all tissues is associated with increased cellular senescence, a stress-response process by which damaged cells leave the cell cycle permanently and produce a pro-inflammatory senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP). These senescent cells accumulate with advancing age causing a pro inflammatory profile.[4]

- Decreased sex steroid hormone levels, after menopause or andropause, is another mechanism for the age-associated increase in systemic IL-6 activity, a pro inflammatory cytokine.[5]

Viewing[edit | edit source]

This 2 minute video gives a simple introduction to the topic.

Diet[edit | edit source]

- The kind of diet adhered to affects inflammaging directly. Healthy diets that include a higher intake of whole grains, vegetables and fruits, nuts and fish appear to counteract the low grade age-related inflammation, for example the Mediterranean diet. Such diets are associated with lower concentrations of inflammatory mediators, like C-reactive protein (CRP) and Tumor Necrosis Factor-α (TNF-α), that are hallmarks of inflammaging.

- An emerging area of research is the microbiome-ageing interaction. Studies show dysbiosis plays a role in sub-optimal metabolism, immune function and brain function, which all contribute to the poor health and impaired well-being associated with ageing. Modulation of the gut microbiota is showing promising results in some disorders[1].

- Contributors to inflammaging include adipose tissue and dietary fat. Excessive intake of lipids can modify the gut microbiota contributing to metabolic endotoxemia, whilst omega 3 fatty acids (in eg fish oils) seem to attenuate this change. The aging-related increase and redistribution of body fat stand (higher fat content) allows the infiltration of M1 macrophages and T lymphocytes. These immune cells, and the adipocytes themselves, release cytokines and chemokines increasing the inflammatory profile.[2]

Exercise[edit | edit source]

It is known that decreased physical activity has a detrimental role in muscle quality, and inappropriate nutritional habits hasten the process of immunosenescence and inflammaging.

- Inflammaging has been associated with increased risk for skeletal muscle wasting, strength loss and functional impairments. Studies performed in animals and cell cultures show increased concentrations of pro-inflammatory cytokines (such as IL-6 and TNF-α as well as increased levels of C-reactive protein).

- Physical activity can alter the systemic inflammation of older adults regardless of their level of intensity, reducing blood fibrinogen and C-reactive protein levels. [2][7]

Senolytics[edit | edit source]

A new class of agents, which annihilate senescent cells named ‘senolytics’ are hoped to bring about a reduction in the inflammatory load in the older person. Senolytics thus far tested include dasatinib (D, a FDA-approved tyrosine kinase inhibitor), quercetin (Q, a flavonoid present in many fruits and vegetables), navitoclax, A1331852 and A1155463 (Bcl-2 pro-survival family inhibitors) and fistein (F, a flavonoid). Results from trials to date are helping to determine the safety and efficacy of senolytics, which may transform the care and treatment of older adults and patients with multiple chronic diseases. Pre-clinical studies conducted in mice have shown senolytics destroy senescent cells resulting in delaying, preventing or alleviating multiple age- and senescence-related conditions, for example frailty, cataracts, age-related osteoporosis, age-related muscle loss, radiation-induced damage, cardiac dysfunction, vascular dysfunction and calcification, pulmonary fibrosis, hepatic steatosis, metabolic syndrome, diabetes and dementia.[4]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Di Giosia P, Stamerra CA, Giorgini P, Jamialahamdi T, Butler AE, Sahebkar A. The role of nutrition in inflammaging. Ageing Research Reviews. 2022 Feb 24:101596. Available:https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35219904/ (accessed 29.7.2022)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Padilha de Lima A, Macedo Rogero M, Araujo Viel T, Garay-Malpartida HM, Aprahamian I, Ribeiro SM. Interplay between Inflammaging, Frailty and Nutrition in Covid-19: Preventive and Adjuvant Treatment Perspectives. The journal of nutrition, health & aging. 2021 Dec 28:1-0. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8713542/ (accessed 29.7.2022)

- ↑ Serrano-López J, Martín-Antonio B. Inflammaging, an Imbalanced Immune Response That Needs to Be Restored for Cancer Prevention and Treatment in the Elderly. Cells. 2021 Sep 28;10(10):2562. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8533838/(accessed 30.7.2022)

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Ellison-Hughes GM. First evidence that senolytics are effective at decreasing senescent cells in humans. EBioMedicine. 2020; 56: 102473. Available: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/ebiom/article/PIIS2352-3964(19)30641-3/fulltext(accessed 30.7.2022)

- ↑ Kim MK, Song YS. Stress Response, Inflammaging, and Cancer. InInflammation, Advancing Age and Nutrition 2014 Jan 1 (pp. 49-53). Academic Press. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/biochemistry-genetics-and-molecular-biology/inflammaging (accessed 30.7.2022)

- ↑ LIV Health. What is Inflammaging. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=aDEAXa9JSBs [last accessed 29/7/2022]

- ↑ NIH Clinical trials Available:https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03308747 (accessed 29.7.2022)