Core Strengthening: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 50: | Line 50: | ||

== Activating the Core == | == Activating the Core == | ||

Rib cage | === Optimal postures === | ||

* Rib cage | |||

** Ribs in location to pelvis | |||

*** Rib cage should be neutral over pelvis for maximum activation of the inner core.<ref>Lee DG. The Pelvic Girdle E-Book: An integration of clinical expertise and research. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2011 Oct 28.</ref> | |||

* Abdominal wall | |||

** Look out for doming in the abdominal muscles | |||

*** This may indicate: | |||

**** Breath holding and creating a vacuum | |||

Abdominal wall | **** Exercise is too difficult – rectus abdominis weak and contracting using a poor pattern | ||

**** Be careful – pressure in the perineum area or bulging - may aggravate pelvic organ prolapse | |||

Look out for doming in the abdominal muscles | |||

This may indicate: | |||

Breath holding and creating a vacuum | |||

Exercise is too difficult – rectus abdominis weak and contracting using a poor pattern | |||

Be careful – pressure in the perineum area or bulging - may aggravate pelvic organ | |||

* Another red flag to look out for: | |||

** Any type of incontinence symptoms or pelvic pain – may indicate that breathing strategy is wrong, exercise too difficult and you need to adapt or decrease the level of exercise and ensure proper breathing strategy<ref>Casey EK, Temme K. Pelvic floor muscle function and urinary incontinence in the female athlete. The Physician and sportsmedicine. 2017 Oct 2;45(4):399-407.</ref> | |||

Activating the Core – Static | Activating the Core – Static | ||

Revision as of 10:49, 29 March 2021

This article or area is currently under construction and may only be partially complete. Please come back soon to see the finished work! (29/03/2021)

Original Editor - Deborah Riczo

Top Contributors - Wanda van Niekerk, Kim Jackson, Tarina van der Stockt, Vidya Acharya and Olajumoke Ogunleye

What is Core?[edit | edit source]

In the literature, consumer as well as academic literature, there are various definitions available of what the core is and what core strengthening is. Even between various health professionals there seems to be a wide definition of what core work is.

The core muscles are involved in maintaining spinal and pelvic stability and can be divided into two groups, according to function.[1] The first group of muscles is the inner core or deep core muscles. This group of muscles is also known as the local stabilising muscles.[1] Hodges et al (1996)[2] showed that the inner core acts in an anticipatory way and that these muscles are activated and fire before the global muscles are activated.

The inner core muscles include:[3][4]

- Pelvic floor muscles

- Transversus abdominis

- Internal Obliques

- Multifidus

- Diaphragm

- Some literature also includes the deep fibres of the psoas and the deep hip rotators as part of the inner core.

The outer core muscles or the global muscles are also referred to as the “movers” and include:[1][3]

- Rectus abdominis

- Internal and external obliques

- Erector spinae

- Qudratus lumborum

- Hip muscle groups

Integrated Model of Function[edit | edit source]

When the core muscles function normally, segmental spinal stability is maintained, the spine and pelvic area is protected and the stress or load that may influence the lumbar vertebrae and intervertebral discs are reduced.[1] In the case of a dysfunction, such as a weak inner core, the outer core compensates for this weakness. Although the outer core muscles’ main function is movement and not stability it is able to contribute to stability with unexpected tasks or overload. As a result of this, splinting occurs and this leads to neuromusculoskeletal issues such as muscle spasms, neural compression and pain.[5]

Abdominal Canister[edit | edit source]

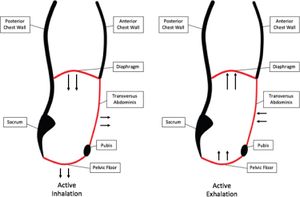

The inner core muscles all form part of the abdominal canister.

The abdominal canister functions similar to the action of a piston. As the diaphragm expands during inspiration, it lowers and presses down on the contents of the abdomen.[6] To allow for this pressure, the pelvic floor muscles relax and elongate. Below is a short summary of how the abdominal canister functions to facilitate breathing:[6]

Inspiration

- Diaphragm contracts and flattens

- Chest wall expands

- Creates negative pressure in thorax, drawing air into the lungs

- Descent of diaphragm also causes expansion of abdominal wall and pelvic floor, due to increase in abdominal pressure

During quiet breathing – exhalation:

- Diaphragm recoils to resting position

- Passive expulsion of air from the lungs

- Abdominal wall and pelvic floor gently contract to return to resting position

Increased respiratory demand – active exhalation:

- Increases air expulsion efficiency to accelerate gas exchange

- Accessory respiratory muscles contract to speed up diaphragm elevation

- Pelvic floor and abdominal muscles are included within these accessory muscles – as they contract more forcefully – create a cranially directed increase in intra-abdominal pressure – this assists with diaphragm elevation.[6]

Activating the Core[edit | edit source]

Optimal postures[edit | edit source]

- Rib cage

- Ribs in location to pelvis

- Rib cage should be neutral over pelvis for maximum activation of the inner core.[7]

- Ribs in location to pelvis

- Abdominal wall

- Look out for doming in the abdominal muscles

- This may indicate:

- Breath holding and creating a vacuum

- Exercise is too difficult – rectus abdominis weak and contracting using a poor pattern

- Be careful – pressure in the perineum area or bulging - may aggravate pelvic organ prolapse

- This may indicate:

- Look out for doming in the abdominal muscles

- Another red flag to look out for:

- Any type of incontinence symptoms or pelvic pain – may indicate that breathing strategy is wrong, exercise too difficult and you need to adapt or decrease the level of exercise and ensure proper breathing strategy[8]

Activating the Core – Static

Supine position

Knees can be straight or bent

If the pelvic floor muscles are very weak, the hips can be elevated over a wedge or pillow – this way gravity is assisting and taking the weight of the pelvic floor

Activate diaphragm with diaphragmatic breathing and using umbrella imagery

Exhale through pursed lips

Pelvic floor activation with exhale

Cues such as: Stopping flatulence or the flow of urine

Transversus abdominis activation

Cues such as : Zip up tight jeans; drawing in manoeuvre; blowing up a balloon

Static core activation can be performed in various positions, for example:

Prone, 4-point kneeling, half-kneeling, standing

A caveat to consider when prescribing static core activation exercises to a client is if the patient is showing symptoms of pelvic floor tightness issues, such as pelvic pain, pain with bowel movements, pain increasing with contraction, etc. In such cases, the patient should refrain from adding the pelvic floor contraction and rather focus on relaxing the pelvic floor.

Activating the core – Dynamic

Core strength can be challenged by adding movement

This can be done in various positions and with various movements

Some examples are:

Supine

Adding alternate arm reaches – focus on elongation of lattisimus dorsi as well with this movement

Adding alternate knee lifts – important to monitor if the patient’s core is able to control the weight of the leg with this movement. A way to do this is to ask patient to place hands on ASIS while performing exercise. If ASIS’s are unable to remain stable with alternate knee lifts, rather prescribe an exercise such as heel slides or knee fall-outs (bent knee abduction and adduction) to start with.

Combine opposite arm and leg

Adding knee extension as a progression from alternate knees in supine

Straight leg raise - make sure your client is strong enough for this exercise

Prone

Adding Dynamic movements:

Glut sets with core activation

Adding hip extension – if open chain to difficult start with closed chain – keep toe on the ground and lift knee

Alternate arms/legs

4-point kneeling

Some caveats to remember with this position:

Avoid this position in a patient with too large of a DRA

Avoid this position in a patient who is in the later stages of pregnancy and has a DRA

Progression from static to dynamic

Adding alternate arms

Alternate arms and legs

½ kneeling

Good position for core strengthening as it also incorporates balance training as well

Progression from static to dynamic

Alternate arms reach – aim for good excursion in lattisimus dorsi

Trunk rotation

Can add light weights

Standing

Progression from static to dynamic

Standing alternate arm raises, add exercises with theraband

Make use Bodyblade

Bosu

Important to also focus on balance exercises, as evidence shows that pregnant women have decreased standing balance and are at a higher risk for falls, especially during the 3rd trimester

Higher level Exercises

Plank on elbows

Start of on knees, progress to on toes

Side-plank

Single leg bridge

4-point alternate arm/leg balance

Progress to whole body movements, agility and balance

Lunges

Stepping

Stepping to the side

Side squats

High stepping, hand to opposite heel while moving

Summary

Core strengthening is effective from the inside (inner core first) to the outside. Modifications of level of difficulty of exercises and breathing strategies can help avoid symptoms of doming, bulging, leaking and pain. It also motivates the patient when improvements are evident and challenges the patient in small incremental steps.

Sub Heading 2[edit | edit source]

Sub Heading 3[edit | edit source]

Resources[edit | edit source]

- bulleted list

- x

or

- numbered list

- x

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Chang WD, Lin HY, Lai PT. Core strength training for patients with chronic low back pain. Journal of physical therapy science. 2015;27(3):619-22.

- ↑ Hodges PW, Richardson CA. Inefficient muscular stabilization of the lumbar spine associated with low back pain: a motor control evaluation of transversus abdominis. Spine. 1996 Nov 15;21(22):2640-50.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Akuthota V, Ferreiro A, Moore T, Fredericson M. Core stability exercise principles. Current sports medicine reports. 2008 Jan 1;7(1):39-44.

- ↑ Saiklang P, Puntumetakul R, Swangnetr Neubert M, Boucaut R. The immediate effect of the abdominal drawing-in maneuver technique on stature change in seated sedentary workers with chronic low back pain. Ergonomics. 2021 Jan 2;64(1):55-68.

- ↑ Key J. ‘The core’: understanding it, and retraining its dysfunction. Journal of bodywork and movement therapies. 2013 Oct 1;17(4):541-59.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Siracusa C, Gray A. Pelvic Floor Considerations in COVID-19. Journal of Women's Health Physical Therapy. 2020 Oct;44(4):144.

- ↑ Lee DG. The Pelvic Girdle E-Book: An integration of clinical expertise and research. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2011 Oct 28.

- ↑ Casey EK, Temme K. Pelvic floor muscle function and urinary incontinence in the female athlete. The Physician and sportsmedicine. 2017 Oct 2;45(4):399-407.