Cubital Tunnel Syndrome: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

<div class="editorbox"> | <div class="qualityalertbox"> | ||

'''Original | This article requires a page merger with a similar article of a similar name or containing repeated information. ({{CURRENTDAY}} {{CURRENTMONTHNAME}} {{CURRENTYEAR}}) | ||

</div> <div class="editorbox"> | |||

'''Original Editors '''- [[User:Adam West|Adam West]], [[User:Fitim Camaj|Fitim Camaj]] and [[User:Lindsey Katt|Lindsey Katt]] | |||

'''Top Contributors''' - {{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}} | '''Top Contributors''' - {{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}} | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

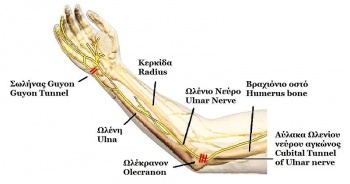

[[Image:Cubital Tunnel Syndrome Definition.jpg|frame|left|Anatomy of Cubital Tunnel]]Cubital tunnel syndrome (CBTS) is a progressive entrapment neuropathy of the ulnar nerve at the medial | |||

== Definition/Description == | |||

Cubital tunnel syndrome is a peripheral nerve compression syndrome. It is an irritation or injury of the ulnar nerve in the cubital tunnel at the elbow. This is also called an entrapment of the ulnar nerve and is the second most common compression neuropathy in the upper extremity following carpal tunnel syndrome.<ref name="Palmer">Palmer BA, Hughes TB. Cubital Tunnel Syndrome. J Hand Surg. 2010; 35(1): 153–163.</ref> <ref name="Han">Han HH, Kang HW, Lee JL, Jung S. Fascia Wrapping Technique: A Modified Method for the Treatment of Cubital Tunnel Syndrome. The Scientific World Journal. 2014; Article ID 482702, 6 pages. doi:10.1155/2014/482702</ref> It represents a source of considerable discomfort and disability for the patient and may in extreme cases lead to loss of function from the hand. Cubital tunnel syndrome is often misdiagnosed.<ref name="Cutts">Cutts S. Cubital tunnel syndrome. Postgrad Med J. 2007 Jan; 83(975): 28–31.</ref> | |||

<br>Peripheral nerve compression syndromes consist of chronic irritation and pressure lesions on sites where nerves have to pass through narrow anatomic spaces and fibro- osseous. The main clinical manifestation of this type of compression syndromes are paresthesia, sensory impairment and paresis. <ref name="Assmus">Assmus H, Antoniadis G, Bischoff C. Carpal and cubital tunnel and other, rarer nerve compression syndromes. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2015 Jan 5;112(1-2):14-25; quiz 26.</ref> | |||

<br>Cubital tunnel syndrome can also be caused by traction, pressure or ischemia of the ulnar nerve which passes through the cubital tunnel at the medial side of the elbow.<ref name="Lund">Lund AT, Amadio PC. Treatment of cubital tunnel syndrome: perspectives for the therapist. J Hand Ther. 2006 Apr-Jun;19(2):170-8.</ref> | |||

<br>The pain or paraesthesia in the fourth and fifth finger and pain in the medial aspect of the elbow which may extend proximally or distally is caused by the compression of the ulnar nerve. The occurrence of cubital tunnel syndrome is associated with “holding a tool in position”. However there's only limited evidence that prove the effectiveness of nonsurgical and surgical interventions to treat cubital tunnel syndrome. <ref name="Cutts" /> <ref name="Rinkel">Rinkel WD, Schreuders TA, Koes BW, Huisstede BM. Current evidence for effectiveness of interventions for cubital tunnel syndrome, radial tunnel syndrome, instability, or bursitis of the elbow: a systematic review. Clin J Pain. 2013 Dec;29(12):1087-96.</ref><br> | |||

== Clinically Relevant Anatomy == | |||

[[Image:Ulnar nerve anatomy.JPG|thumb|right|350px|Ulnar Nerve Anatomy including Cubital Tunnel]] | |||

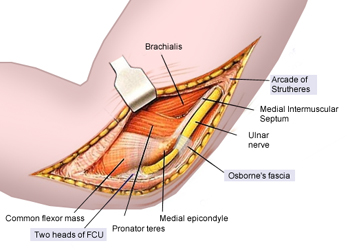

[[Image:Cubital Tunnel Syndrome Definition.jpg|frame|left|Anatomy of Cubital Tunnel]]Cubital tunnel syndrome (CBTS) is a progressive entrapment neuropathy of the ulnar nerve at the medial aspect of the elbow. The ulnar nerve, which is a motor and sensory nerve, is formed from the medial cord of the brachial plexus, which originates from nerve roots C8 and T1.<ref name="Feindel">Feindel W, Stratford J. Cubital tunnel compression in tardy ulnar nerve palsy. Can Med Assoc J. 1958;78:351.</ref><ref name="Osborne">Osborne GV. The surgical treatment of tardy ulnar neuritis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1957;39B:782.</ref><ref name="Tetro">Tetro AM, Pichora DR. Cubital tunnel syndrome and the painful upper extremity. Hand Clin. 1996;12(4):665-677.</ref> The ulnar nerve travels down the posterior aspect of the arm to eventually traverse posterior to the medial epicondyle through an area known as the cubital tunnel. The cubital tunnel extends from the medial epicondyle of the humerus to the olecranon process of the ulna.<ref name="Wheeless">Wheeless CR. Cubital tunnel syndrome. http://www.wheelessonline.com/ortho/cubital_tunnel_syndrome. Updated June 5, 2010. Accessed November 1, 2010.</ref> The nerve runs superficial to the ulnar collateral ligament (UCL) and deep to the aponeurotic attachment of the flexor carpi ulnaris (FCU), which is also known as Osborne’s ligament. Once the ulnar nerve reaches the proximal border of Osborne’s ligament it is located in the cubital tunnel. | |||

<br>The roof of the cubital tunnel is formed by the cubital tunnel retinaculum (also known as Osborne’s ligament) which is about 4 mm between the medial epicondyle and the olecranon. The floor of the tunnel consists of the elbow joint capsule and the posterior band of the medial collateral ligament of the elbow. It contains several structures; the most important of these is the ulnar nerve.<ref name="Cutts" /> <br> <br>After passing through the cubital tunnel, the ulnar nerve is inserted deep into the forearm between the ulnar and humeral heads of the flexor carpi ulnaris. | |||

The ulnar nerve entrapment can occur at 5 sites around the elbow: <br>- Arcade of Struthers (approximately 10cm proximal to the medial epicondyle) <br>- Medial intermuscular septum (runs from the arcade to the epicondyle)<br>- Medial epicondyle<br>- Cubital tunnel (retinaculum)<br>- Deep flexor pronator aponeurosis (about 5cm distal to the epicondyle)<ref name="Lund" /> <br>Out of all the 5 sites, the cubital tunnel is the most common site for entrapment.<ref name="Palmer" /> | |||

== Epidemiology /Etiology == | == Epidemiology /Etiology == | ||

Cubital tunnel syndrome is the | Cubital tunnel syndrome may be a result of direct or indirect trauma and is vulnerable to traction, friction, and compression. Traction injuries may be the result of longstanding valgus deformity and flexion contractures, but are most common in throwers due to extreme valgus stress placed on the arm. <ref name="Lee">Lee ML, Rosenwasser MP. Chronic elbow instability. Orthop Coin North Am. 1999;30:81-89.</ref> Compression of the nerve at the cubital tunnel may occur due to reactive changes at the MCL, adhesions within the tunnel, hypertrophy of the surrounding musculature, or joint changes.<ref name="Aldridge">Aldridge JW, Bruno RJ, Strauch RJ, Rosenwasser MP. Nerve entrapment in athletes. Clin Sports Med. 2001;20:95-122.</ref><br> | ||

Cubital tunnel syndrome consists of compression of the ulnar nerve in the cubital tunnel under Osborne’s ligament and often with a conductive component from nerve stretching. The cause of this syndrome can be classified into primary or secondary reasons:<br>- Primary (idiopathic) include: anatomical variants such as subluxation of the ulnar nerve or an epitrochlearis-anconeus muscle which is a rare cause of cubital tunnel syndrome. <ref name="Uscetin">Uscetin I, Bingol D, Ozkaya O, Orman C, Akan M. Ulnar nerve compression at the elbow caused by the epitrochleoanconeus muscle: a case report and surgical approach. Turk Neurosurg. 2014; 24(2):266-71.</ref> <br>- Secondary (symptomatic) include: a delayed ulnar paresis due to trauma or elbow arthrosis. It can also be caused by extra neural or, less commonly, intraneural masses, such as a lipoma or ganglion.<ref name="Assmus" /> | |||

<br> | |||

There are many factors which can lead to cubital tunnel syndrome. They include:<br>- Mechanical factors such as stretching of, friction on, or compression of the ulnar nerve <ref name="Bruce">Bruce SL, Wasielewski N, Hawke RL. Cubital tunnel syndrome in a collegiate wrestler: a case report. J Athl Train. 1997 Apr;32(2):151-4.</ref> <ref name="Assmus" /><br>- Direct trauma or other space-occupying lesion, repetitive elbow flexion/extension, repetitive overhead activities, traction, subluxation of the ulnar nerve from the ulnar groove, metabolic disorders, congenital deformities, synovial cysts, anatomical irregularities, arthritis, joint inflammation, and occupational/athletic factors.<ref name="Bruce" /> | |||

<br>Obesity is considered a strong contributing factor to cubital tunnel syndrome. <br>The ulnar nerve is very vulnerable to external pressure as it runs along the condylar groove where it lies superficial and unprotected. | |||

Symptoms can sometimes be associated with other conditions such as: osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis and other diseases, for example: diabetes mellitus, haemophilia. | |||

Symptoms can be aggravated by alcoholism, obesity and smoking. | |||

One of the most common pathogenetic mechanisms is intermittent traction when the ulnar nerve becomes fixed at a single or several points which limits the free gliding of the nerve.<ref name="Lund" /> <br> | |||

== Characteristics/Clinical Presentation == | == Characteristics/Clinical Presentation == | ||

Early in the disorder, primary complaint is typically medial elbow pain. Numbness and tingling may also be present in the 4th and 5th digits. The patient may also report non-painful "snapping" or "popping" during active and passive flexion and extension of the elbow. A Wartenberg sign (abduction of the fifth digit due to weakness of the third palmar interosseous muscle) may be present. Active and passive ROM may not be decreased. The ulnar nerve may be enlarged or palpable and tender in the groove.<ref name="Sebelski">Sebelski CA. Current concepts of orthopaedic physical therapy. The Elbow: physical therapy management utilizing current evidence.</ref><br> | |||

– Onset of this syndrome is often acute, with numbness or paraesthesia of the 4th and 5th fingers <ref name="Houston">Houston Methodist Orthopedics &amp;amp;amp;amp;amp; Sports Medicine: A Patient's Guide to Cubital Tunnel Syndrome. http://www.methodistorthopedics.com/Cubital-Tunnel-Syndrome</ref> | |||

– aching pain in the forearm <ref name="Wolgi">Wolgi MA. Ohttp://www.drwolgin.com/Pages/CubitalTunnelSyndr.aspx</ref> | |||

– atrophy of the intrinsic muscles of the hand, which is often not noticed by the patient<br>– delayed paresis after old elbow joint injury<br>– hypoesthesia of the ulnar 1 1/2 digits, the ulnar side of the dorsum of the hand, and the hypothenar eminence. <ref name="Wojewnik">Wojewnik B, Bindra R. Cubital tunnel syndrome - Review of current literature on causes, diagnosis and treatment. J Hand Microsurg. 2009; 1(2):76-81.</ref> | |||

– incomplete or absent adduction of the little finger<br>– tenderness and (often) thickening of the ulnar nerve at the elbow / in the sulcus ulnaris<br>– atrophy of the intrinsic muscles of the hand innervated by the ulnar nerve, with abnormal claw posture of the 4th and 5th fingers <ref name="Assmus" /> | |||

<br>There are many different ways to grade this neuropathy. There have been some studies on whether or not these ways have a clinical meaning and if they can be used as guidelines for therapy. These studies aren't conclusive.<ref name="Qing">Qing C, Zhang J, Wu S, Ling Z, Wang S, Li H, Li H. Clinical classification and treatment of cubital tunnel syndrome. Exp Ther Med. 2014 Nov;8(5):1365-1370.</ref> <ref name="Watanabe">Watanabe M, Arita S, Hashizume H, Honda M, Nishida K, Ozaki T. Multiple regression analysis for grading and prognosis of cubital tunnel syndrome: assessment of Akahori's classification. Acta Med Okayama. 2013;67(1):35-44.</ref><br>Patients suffering from cubital tunnel syndrome are 4 times more likely to present with atrophy than patients suffering from carpal tunnel syndrome. The ulnar nerve dysfunction has been divided into three categories by McGowan and has modified by Dellon:<br>• Mild nerve dysfunction implies intermittent paraesthesia and subjective weakness. <br>• Moderate dysfunction presents with intermittent paraesthesia and measurable weakness. <br>• Severe dysfunction is characterized by persistent paraesthesia and measurable weakness.<ref name="Palmer" /> <br> | |||

== Diagnostic Procedures == | |||

The diagnosis is established by the history and physical examination, along with the findings of electro-physiologic studies and imaging. <br> | |||

Imaging<br> | |||

– with high-resolution neuro-ultrasonography, demonstration of changes in the size and position of the ulnar nerve at the elbow (also of changes in the echo texture of the nerve) <br>– magnetic resonance neurography (MRN) enables the visualization of structural changes of the ulnar nerve and its environment <ref name="Assmus" /> | |||

X-rays can be used to look for degenerative changes of the cervical spine and elbow, as well as bony compression from spurs or previous fractures. In establishing diagnosis, neurophysiological studies are helpful and should be done if surgery is planned, in order to document preoperative baseline. Ulnar nerve velocity of <50 m/s at the elbow is considered positive for cubital tunnel syndrome. <ref name="Wojewnik" /> <br>Tinel’s signs are also used in the diagnostic procedure. These are also used in the diagnosis of tarsal tunnel syndrome.<ref name="Qing" /> <br> | |||

== Outcome Measures == | |||

McGowan Score, Louisiana State University Medical Center Score, Bishop Score, and Medical Research Council grade, and [[The Northwick Park Questionnaire|Northwick Park Questionnaire]] are a few outcome measures that have been used.<ref name="Zlowodzki">Zlowodzki M, Chan S, Bhandari M, Kalliamen L, Schubert W. Anterior transpositin compared with simple decompressin for treatment of cubital tunnel syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:2591-8.</ref> Quick Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand questionnaire and the Short Form-12 can also be use. <ref name="Shah">Shah CM, Calfee RP, Gelberman RH, CA Goldfarb. Outcomes of Rigid Night Splinting and Activity Modification in the Treatment of Cubital Tunnel Syndrome. J Hand Surg. 2013; 38(6): 1125–1130.</ref> | |||

== Examination == | == Examination == | ||

Tests used to confirm the diagnosis of cubital tunnel syndrome are those linking the ulnar neuropathy and the elbow. These tests should evoke provocative signs as a reaction to confirm this syndrome such as: elbow flexion reproducing symptoms, positive Tinel’s sign tested at the elbow or a sign of instability, for example the snapping of the ulnar nerve over the medial epicondyle with elbow flexion.<ref name="Lund" /> <br>The Elbow Flexion Test: Typically performed bilaterally with the shoulder in full external rotation and the elbow actively held in maximal flexion with wrist extension for one minute. A positive test is reproduction of numbness and tingling in the ulnar distribution on the involved side. Specificity (0.99) Sensitivity (0.75). <ref name="Novak" /> | |||

<br>When maximal elbow flexion is effectuated, symptoms are produced because the cubital tunnel volume is reduced by approximately 55% which causes an increase in neural pressure on the ulnar nerve. Some studies state that additional components such as wrist extension and wrist flexion or sustained maximal elbow flexion for up to three minutes can be included. These studies also state that quicker signs of a positive test are more indicative of a true diagnosis of cubital tunnel syndrome. The test is positive when pain is felt at the medial side of the elbow and numbness and tingling in the ulnar distribution on the involved side. This test has a high positive predictive value (0.97), which indicates a high probability of cubital tunnel syndrome if positive. (CTSII page)<br> | |||

<br>The Pressure Provocative Test: The clinician applies pressure at the ulnar nerve at the cubital tunnel with the UE positioned as in the elbow flexion test for 30 seconds. Sensitivity (0.91).<ref>Novak</ref><br>Tinel Sign: Reproduction of tingling and numbness into the 4th and 5th digits with tapping of the ulnar nerve at the cubital tunnel. Specificity (0.98), Sensitivity (0.70).<ref name="Novak" /> | |||

<br>The clinician will proceed with percussions (tapping) on the ulnar nerve as it passes through the cubital tunnel after the ulnar groove posterior of the medial epicondyle of the humerus is located. The number of percussions may vary depending on the research, but four to six taps should be sufficient to obtain symptoms. A positive test is the reproduction of tingling and numbness in the ulnar nerve distribution on the involved side. Cautions must be taken in the interpretation of the test because it has been found positive in 24% of asymptomatic subjects and it could be negative for those in the advanced stage of the diagnosis due to the fact that the nerve is no longer regenerating. (CTSII page) | |||

<br>The “scratch collapse” test: To perform the scratch collapse test, the patient’s skin is lightly scratched by the examiner over the area of nerve compression while the patient performs resisted bilateral shoulder external rotation. A brief loss of muscle resistance will be elicited if the patient has allodynia due to the compression neuropathy. Sensitivity for the scratch collapse was 69% compared with 54% and 46% for Tinel test and elbow flexion compression test, respectively. Of all tests for cubital tunnel, Tinel test had the highest negative predictive value (98%).<ref name="Palmer" /> | |||

== Medical Management <br> == | |||

{| width="40%" cellspacing="1" cellpadding="1" border="0" align="right" class="FCK__ShowTableBorders" | |||

|- | |||

| align="right" | <br> | |||

| {{#ev:youtube|qttiyxBP0uM|250}} <ref>reimerhoffman. Endoscopic Cubital Tunnel Syndrome. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qttiyxBP0uM [last accessed 22/03/13]</ref> | |||

|} | |||

<u>Operative Management</u>: Indications for surgical intervention include failure of conservative treatment and an electrodiagnostic test of less than 39 meters per second across the elbow.<ref name="Novak">Novak CB, Lee GW, Mackinnon SE, Lay L. Provocative testing for cubital tunnel syndrome. J Hand Surg Am. 1994 Sep;19(5):817-20.</ref> Several surgical techniques have been advocated for cubital tunnel syndrome. Techniques include: simple decompression, submuscular anterior transposition, and subcutaneous anterior ulnar transposition. Results found no difference in motor nerve-conduction velocities or clinical outcome scores between simple decompression and ulnar nerve transposition. <ref name="Zlowodzki">Zlowodzki M, Chan S, Bhandari M, Kalliainen L, Schubert W. Anterior transposition compared with simple decompression for treatment of cubital tunnel syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:2591-8.</ref> | |||

<br>< | Surgery is indicated in case of: <br>● progressive symptoms, <br>● sensorimotor deficits, <br>● lack of clinical and electro-neurographic improvement<br>● worsening of the objective findings on follow up several weeks after the initial visit. <br>Decompression is the mostly performed as surgical treatment. <ref name="Assmus" /> | ||

<br>A recent study from 2014 investigated whether fascia wrapping would be a good surgical method and it found good results. Fascia wrapping is a type of sub-facial trans-positioning. This method provides better immobilization and requires less dissection than a sub-fascial transposition. All surgical treatments have disadvantages and advantages. It depends on the surgeon which method will be used. <ref name="Han" /><br>Simple decompression: A 6- to 10-cm incision is made along the course of the ulnar nerve between the medial epicondyle and the olecranon. Care should be taken to avoid the branches of the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve. Osbourne’s ligament is released as are the FCU superficial and deep fascia. It has been shown to be successful in treating cubital tunnel syndrome. Data suggests that in situ decompression is a reliable treatment with a low failure rate, and anterior trans-positioning can be used to treat those patients with recurrent symptoms. | |||

< | <br>There are three types of anterior transposition techniques that are named in relation to the flexor-pronator mass: <br> o Subcutaneous (above)<br> o Intermuscular (within)<br> o Sub-muscular (below)<br>Subcutaneous trans-positioning is another common surgical treatment for cubital tunnel syndrome. Its goal is to move the ulnar nerve anterior to the elbow axis of flexion, decreasing the tension on the nerve. | ||

<br>Intramuscular trans-positioning is another technique performed in combination with anterior trans-positioning of the nerve. Proponents of this technique believe that this places the nerve in a straighter line across the elbow joint. Opponents argue that scarring of the nerve can be caused, which serves as the bed for the transposed nerve. The procedure is similar to the subcutaneous trans-positioning; however a groove is created in the flexor-pronator muscle mass to serve as a tract into which the nerve is transposed. <br>Sub-muscular trans-positioning: Some surgeons prefer to place the nerve complete beneath the flexor-pronator mass. The branches of the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve are identified and protected. The ulnar nerve is identified and decompressed as in subcutaneous trans-positioning. | |||

< | Medial epicondylectomy: It’s described in the treatment of ulnar nerve palsy.<ref name="Palmer" /> Geutjens et al. have found limited evidence that shows that the medial anterior epicondylectomy offers a significantly better pain score than the ulnar nerve transposition in the treatment of cubital tunnel syndrome at long-term follow-up.<ref name="Geutjens">Geutjens GG, Langstaff RJ, Smith NJ, Jefferson D, Howell CJ, Barton NJ. Medial epicondylectomy or ulnar-nerve transposition for ulnar neuropathy at the elbow? J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1996 Sep;78(5):777-9.</ref> <br>Endoscopic decompression: It is the decompression of the ulnar nerve at the elbow. All techniques used a small 15-mm to 35-mm incision located over the ulnar nerve at the condylar groove. The variations rely on different techniques of retraction of subcutaneous tissues for visualization of the nerve. <br>Cubital tunnel syndrome is a common nerve compression with a variety of treatment options. Multiple surgical options exist that have been shown to ease symptoms. Selection of a surgical approach is based on the etiology of nerve compression, anatomic variations, and the surgeon’s experience. With careful protection of the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve and careful complete decompression of the nerve around the elbow, with or without transposition, good results can be obtained.<ref name="Palmer" /> <br> | ||

== Physical Therapy Management <br> == | |||

<u></u> | |||

Initial goal of the conservative treatment for cubital tunnel syndrome is to control and decrease paraesthesia and pain. When the symptoms are mild and aggravating activities can be identified, the first step is eliminating those pain provocative activities. When symptoms occur in a wider range of activities which also possibly include work, therapy becomes more complex and can consist of activity modifications, splinting and rest. With this combination, pain and paraesthesia become more controllable. | |||

<br>The therapy begins with education about the development of the symptoms and how certain activities can have an influence on these symptoms. The therapist begins with explaining the origin of the ulnar nerve and how it is orientated in one’s body. This makes it easier to explain how certain movements can provoke pain such as stretching or compressing the nerve when collaterally tilting the head or abducting, depressing or external rotating the shoulder, supinating the forearm or extending the wrist. The therapist has to teach the patient to be able to analyse these movements during everyday activities and to make sure that provoking movements are not being made repetitively, which could cause aggravation of the symptoms. For many patients this could mean a lifelong management.<ref name="Lund" /> | |||

<br>Other studies show that the effect of rigid night splinting for a time period of three months combined with activity modification seems to be a successful. It has been proven that prolonged elbow flexion (static or repetitive) brings strain on the ulnar nerve and it increases extraneural and intraneural pressure in the cubital tunnel. The lowest value of these pressures is at an elbow position of 40o-50o of flexion. It has also been proven that pressures are significantly higher in full flexion or extension of the elbow. Splinting is meant to alleviate symptoms and prevent the progressive dysfunction of nerves. <ref name="Shah" /> | |||

<br> | <br> | ||

Non-operative Management: Non-operative management has been shown to have at least a 50% success rate with low-stage ulnar irritation. Nonsurgical treatment should be tried for at least 3 months before surgical intervention, especially in mild cases.<ref name="Wojewnik" /> Non-operative management may include a 4-6 week period of immobilization with the elbow splinted at 45 degrees flexion and full supination. It has been recommended that athletes have active rest from sports. Modalities may be used to treat inflammation. Return to throwing is allowed at 4-6 weeks following absence of symptoms with any daily activities or exercise and return to full ROM and strength.<ref name="Shah" /> It also includes soft elbow pads, joint mobilizations, neural flossing and neural gliding, exercise. (CTSII page)<br> | |||

<br>There is some low level evidence (case report ) that has utilized nerve-gliding techniques, segmental joint manipulation and a home program consisting of nerve gliding and light free weight exercises and was able to achieve positive outcomes. <ref name="Coppieters">Coppieters MW, Bartholomeeusen KE, Stappaerts KH. Incorporating nerve-gliding techniques in the conservative treatment of cubital tunnel syndrome. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2004 Nov-Dec;27(9):560-8.</ref> | |||

<br>Beside education of the patient, immobilizing the elbow by the use of splints can reduce swelling and can help to identify the location of nerve irritation. Splinting the elbow in an appropriate way allows the nerve and the surrounding structures to rest and have relief from traction and compression. This method of therapy can be combined with the usage of local steroid injections which cause relief of pain and swelling. Though steroid injections can have positive effects, therapist has to keep in mind that this treatment can have complications such as scarring and atrophy.<ref name="Lund" /> <br> | |||

= | Night splinting has long been considered as an essential conservative treatment for cubital tunnel syndrome, but there are two issues that should bear consideration: the ability of the splint to maintain the elbow at the ideal position of 40-50 degrees of flexion and patient compliance with night splinting.<ref name="Shah" /> <br> | ||

<br>Lund and Amadio point out that in their opinion, avoiding symptom provoking activities can be the most important issue in the therapy of cubital tunnel syndrome. This might also be the most expensive component as the patient may require assistance at home and in the case when during work the symptoms aggravate, it is also not possible for the patient to continue working. Patients are more desperate for a solution and they expect that medical professionals should come up with a fast and effective solution to their problems. This is a big challenge for professionals, as the recovery period of nerves is in some cases unpredictable. <br>Applying ice can also be a solution for reducing pain and swelling, which can be combined with gently applied active range of motion exercises. Patients should know that it’s not recommended to apply ice for longer than 60 minutes. <br>Ultrasound therapy is also an option but only in the case when used properly and with caution as it is also shown to cause further nerve damage when used on inappropriate intensity. This can slow down the speed of recovery. <br>Active range of motion exercises should be initiated within range of comfort, which means up to the point where the patient still does not experience any pain when moving. Stretching can be applied within tolerance and only after the level of pain has decreased.<ref name="Lund" /> <br> | |||

<br> | == Differential diagnosis == | ||

<br>Differential diagnosis should include cervical radiculopathy, thoracic outlet syndrome; MCL (UCL) insufficiency, tophaceous gout, and calcium pyrophosphate dehydrate crystal deposition.<ref name="Shah" /><br>Cubital tunnel syndrome can be often misdiagnosed as C7 syndrome or other circulatory disturbance for example Raynaud's disease or polyneuropathy. <ref name="Assmus" /><br> | |||

The symptoms of cubital tunnel syndrome may be viewed as another condition and are similar to those associated with thoracic outlet syndrome, a C8 Nerve root entrapment, a double-crush syndrome, or a tumor. <ref name="Bruce" /><br>• Cervical Radiculopathy C8-T1: Motor and sensory deficits in a dermatome pattern including 4th-5th digits. It’s associated with weakness of the intrinsic muscles of the hand, and associated with painful and often limited cervical range of motion. <br>• Thoracic Outlet Syndrome: Compression of the structures of the brachial plexus which probably leads to pain, paraesthesia, and weakness in arm, shoulder, and neck.<br>• UCL Insufficiency: Laxity of the UCL can lead to excessive or abnormal movement of structures in or around the cubital tunnel which creates new sites of compression. <br>• Pancoast Tumor: Abnormal growth of tissue on the apex of the lung causing compression of the lower trunk of the brachial plexus. <br> | |||

These diagnoses present similarity to cubital tunnel with pain, paraesthesia, and potential weakness; nevertheless, symptoms specific to each diagnosis allow the specialist to rule out the doppelganger and rule in cubital tunnel syndrome. Examples of such symptoms are limited cervical motion and paraesthesia in other areas outside the ulnar nerve distribution. It is important for clinicians to correctly identify this diagnosis early due to the fact that, studies have shown an 88% improvement rate when treated within one year of onset as opposed to 67% improvement if treated after one year. (CTSII page) | |||

<br>Patients who suffer from cervical radiculopathy feel pain which initiates from the roots of the nerve and radiates to the upper back and the arm. When the upper trunk is affected (roots C5-6), patients experience pain when their arm is in an elevated in a hand-on-head position and creates slack in the brachial plexus. When it comes to patients with cubital tunnel syndrome, extension of the elbow and adduction of the arm would cause the most slacks and thus cause the most relief.<ref name="Lund" /> <br> | |||

== Key Research == | == Key Research == | ||

< | <br> | ||

Zlowodzki and Chan<ref name="Zlowodzki" /> | |||

Meta-Analysis of four RCT comparing simple decompression with anterior ulnar nerve transpostions. There were no significant differences between simple decompression and anterior transposition in terms of the clinical scores in those studies (standard mean difference in effect size = -0.04 [95% CI = -0.36 to 0.28], p = 0.81. Authors did not find significant heterogeneity across the studies. Two reports presented postoperative motor nerve conduction vlocities; they showed no significant difference between the the procedures. Conclusion: Data suggests that simple decompression is a reasonable alternative to anterior transposition for surgical management of ulnar nerve compression at the elbow. | |||

== Resources <br> == | == Resources <br> == | ||

Journal Hand Microsurgery<br>Journal Hand Therapy<br>Journal Hand Surgery<br><br> | |||

== Case Report == | |||

<u>'''Coppieters and Bartholomeeusen'''</u><ref name="Coppieters" /> | |||

The objective was to discuss the diagnosis and treatment of a patient with cubital tunnel syndrome and to illustrate novel treatment modalities for the ulnar nerve and its surrounding structures and target tissues. The patient was a 17 year old female with traumatic onset of cubital tunnel syndrome. She had pain around the elbow and paresthesia in the ulnar nerve distribution. Electrodiagnostic tests were negative. Segmental cervicothoracic motion dysfunctions were presentwhich were regarded as contributing factors hindering natural recovery. Six treatments included nerve-gliding techniques, segmental joint manipulation, and a home program of nerve gliding and light free-weight exercises. Substantial improvement was recorded on both the impairment and functional level. Symptoms did not recur within 10-month follow-up period. Pain and disability had completely resolved. | |||

<u>'''Bruce, Wasielewski and Hawke'''</u><ref name="Bruce" /> | |||

The patient was a 21-year-old male collegiate wrestler diagnosed with cubital tunnel syndrome. He was diagnosed with cubital tunnel syndrome after 6 weeks of increasing disability and dysfunction. He was treated conservatively for 3 months without resolution of the symptoms. Surgical treatment then involved a subcutaneous ulnar nerve transposition performed to decompress the cubital tunnel. Following surgery, the athlete participated in an aggressive rehabilitation program to restore function and strength to the elbow and adjacent joints. He was cleared for full unrestricted activity 15 days following surgery and returned to varsity athletic competition in one month. Their literature review found no reported cases of cubital tunnel syndrome in wrestlers. Cubital tunnel syndrome is usually seen in throwing athletes and results from either acute trauma or repetitive activities. The athletic trainer should consider cubital tunnel syndrome as a possible pathology for nonthrowing athletes when presented with associated signs and symptoms. <ref name="Bruce" /><br> | |||

== Clinical Bottom Line == | == Clinical Bottom Line == | ||

Despite the significant amount of literature devoted to the diagnosis and treatment of cubital tunnel syndrome, optimal treatment often requires two very simple components of treatment - time and rest. While surgical intervention can greatly ease symptoms, successful lifelong management of cubital tunnel syndrome also demands education and a dedicated effort at activity modification. Hopefully, with better environmental work conditions and early detection by the medical community, can the expenses involved, the time spent in rehabilitation, and most importantly the pain and debility these patients experience decrease with the help of the patient and employer, and the medical management team.<ref name="Lund" /> <br> | |||

== Recent Related Research (from [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/ Pubmed]) == | == Recent Related Research (from [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/ Pubmed]) == | ||

<div class="researchbox"><rss>http://eutils.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/erss.cgi?rss_guid= | <div class="researchbox"> | ||

<rss>http://eutils.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/erss.cgi?rss_guid=1tUjNYI-_9Js-9CLZ61f-RfYmnSd5DpJiCYwauPMSVUmHW1ga8|charset=UTF-8|short|max=10</rss> | |||

<br> | |||

</div> | |||

== References == | == References == | ||

<br> | |||

<references /> | <references /> | ||

[[Category: | [[Category:Vrije_Universiteit_Brussel_Project|Template:VUB]] [[Category:Elbow]] [[Category:EIM_Residency_Project]] [[Category:Musculoskeletal/Orthopaedics]] [[Category:Neurodynamics]] [[//www.pinterest.com/pin/create/extension/|//www.pinterest.com/pin/create/extension/]] | ||

Revision as of 01:50, 27 February 2016

This article requires a page merger with a similar article of a similar name or containing repeated information. (31 May 2024)

Original Editors - Adam West, Fitim Camaj and Lindsey Katt

Top Contributors - Lindsey Katt, Greg Propst, Laura Ritchie, Adam West, Rani Sileghem, Scott Cornish, Admin, Kim Jackson, Uchechukwu Chukwuemeka, Boris Alexandra, Anas Mohamed, Zane Richardson, Johnathan Fahrner, WikiSysop, Vidya Acharya, Matthew Malone, Wanda van Niekerk, Amanda Ager, Scott Brown, Jeremy Brady, Scott Buxton, 127.0.0.1 and Rachael Lowe

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

Cubital tunnel syndrome is a peripheral nerve compression syndrome. It is an irritation or injury of the ulnar nerve in the cubital tunnel at the elbow. This is also called an entrapment of the ulnar nerve and is the second most common compression neuropathy in the upper extremity following carpal tunnel syndrome.[1] [2] It represents a source of considerable discomfort and disability for the patient and may in extreme cases lead to loss of function from the hand. Cubital tunnel syndrome is often misdiagnosed.[3]

Peripheral nerve compression syndromes consist of chronic irritation and pressure lesions on sites where nerves have to pass through narrow anatomic spaces and fibro- osseous. The main clinical manifestation of this type of compression syndromes are paresthesia, sensory impairment and paresis. [4]

Cubital tunnel syndrome can also be caused by traction, pressure or ischemia of the ulnar nerve which passes through the cubital tunnel at the medial side of the elbow.[5]

The pain or paraesthesia in the fourth and fifth finger and pain in the medial aspect of the elbow which may extend proximally or distally is caused by the compression of the ulnar nerve. The occurrence of cubital tunnel syndrome is associated with “holding a tool in position”. However there's only limited evidence that prove the effectiveness of nonsurgical and surgical interventions to treat cubital tunnel syndrome. [3] [6]

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

Cubital tunnel syndrome (CBTS) is a progressive entrapment neuropathy of the ulnar nerve at the medial aspect of the elbow. The ulnar nerve, which is a motor and sensory nerve, is formed from the medial cord of the brachial plexus, which originates from nerve roots C8 and T1.[7][8][9] The ulnar nerve travels down the posterior aspect of the arm to eventually traverse posterior to the medial epicondyle through an area known as the cubital tunnel. The cubital tunnel extends from the medial epicondyle of the humerus to the olecranon process of the ulna.[10] The nerve runs superficial to the ulnar collateral ligament (UCL) and deep to the aponeurotic attachment of the flexor carpi ulnaris (FCU), which is also known as Osborne’s ligament. Once the ulnar nerve reaches the proximal border of Osborne’s ligament it is located in the cubital tunnel.

The roof of the cubital tunnel is formed by the cubital tunnel retinaculum (also known as Osborne’s ligament) which is about 4 mm between the medial epicondyle and the olecranon. The floor of the tunnel consists of the elbow joint capsule and the posterior band of the medial collateral ligament of the elbow. It contains several structures; the most important of these is the ulnar nerve.[3]

After passing through the cubital tunnel, the ulnar nerve is inserted deep into the forearm between the ulnar and humeral heads of the flexor carpi ulnaris.

The ulnar nerve entrapment can occur at 5 sites around the elbow:

- Arcade of Struthers (approximately 10cm proximal to the medial epicondyle)

- Medial intermuscular septum (runs from the arcade to the epicondyle)

- Medial epicondyle

- Cubital tunnel (retinaculum)

- Deep flexor pronator aponeurosis (about 5cm distal to the epicondyle)[5]

Out of all the 5 sites, the cubital tunnel is the most common site for entrapment.[1]

Epidemiology /Etiology[edit | edit source]

Cubital tunnel syndrome may be a result of direct or indirect trauma and is vulnerable to traction, friction, and compression. Traction injuries may be the result of longstanding valgus deformity and flexion contractures, but are most common in throwers due to extreme valgus stress placed on the arm. [11] Compression of the nerve at the cubital tunnel may occur due to reactive changes at the MCL, adhesions within the tunnel, hypertrophy of the surrounding musculature, or joint changes.[12]

Cubital tunnel syndrome consists of compression of the ulnar nerve in the cubital tunnel under Osborne’s ligament and often with a conductive component from nerve stretching. The cause of this syndrome can be classified into primary or secondary reasons:

- Primary (idiopathic) include: anatomical variants such as subluxation of the ulnar nerve or an epitrochlearis-anconeus muscle which is a rare cause of cubital tunnel syndrome. [13]

- Secondary (symptomatic) include: a delayed ulnar paresis due to trauma or elbow arthrosis. It can also be caused by extra neural or, less commonly, intraneural masses, such as a lipoma or ganglion.[4]

There are many factors which can lead to cubital tunnel syndrome. They include:

- Mechanical factors such as stretching of, friction on, or compression of the ulnar nerve [14] [4]

- Direct trauma or other space-occupying lesion, repetitive elbow flexion/extension, repetitive overhead activities, traction, subluxation of the ulnar nerve from the ulnar groove, metabolic disorders, congenital deformities, synovial cysts, anatomical irregularities, arthritis, joint inflammation, and occupational/athletic factors.[14]

Obesity is considered a strong contributing factor to cubital tunnel syndrome.

The ulnar nerve is very vulnerable to external pressure as it runs along the condylar groove where it lies superficial and unprotected.

Symptoms can sometimes be associated with other conditions such as: osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis and other diseases, for example: diabetes mellitus, haemophilia.

Symptoms can be aggravated by alcoholism, obesity and smoking.

One of the most common pathogenetic mechanisms is intermittent traction when the ulnar nerve becomes fixed at a single or several points which limits the free gliding of the nerve.[5]

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Early in the disorder, primary complaint is typically medial elbow pain. Numbness and tingling may also be present in the 4th and 5th digits. The patient may also report non-painful "snapping" or "popping" during active and passive flexion and extension of the elbow. A Wartenberg sign (abduction of the fifth digit due to weakness of the third palmar interosseous muscle) may be present. Active and passive ROM may not be decreased. The ulnar nerve may be enlarged or palpable and tender in the groove.[15]

– Onset of this syndrome is often acute, with numbness or paraesthesia of the 4th and 5th fingers [16]

– aching pain in the forearm [17]

– atrophy of the intrinsic muscles of the hand, which is often not noticed by the patient

– delayed paresis after old elbow joint injury

– hypoesthesia of the ulnar 1 1/2 digits, the ulnar side of the dorsum of the hand, and the hypothenar eminence. [18]

– incomplete or absent adduction of the little finger

– tenderness and (often) thickening of the ulnar nerve at the elbow / in the sulcus ulnaris

– atrophy of the intrinsic muscles of the hand innervated by the ulnar nerve, with abnormal claw posture of the 4th and 5th fingers [4]

There are many different ways to grade this neuropathy. There have been some studies on whether or not these ways have a clinical meaning and if they can be used as guidelines for therapy. These studies aren't conclusive.[19] [20]

Patients suffering from cubital tunnel syndrome are 4 times more likely to present with atrophy than patients suffering from carpal tunnel syndrome. The ulnar nerve dysfunction has been divided into three categories by McGowan and has modified by Dellon:

• Mild nerve dysfunction implies intermittent paraesthesia and subjective weakness.

• Moderate dysfunction presents with intermittent paraesthesia and measurable weakness.

• Severe dysfunction is characterized by persistent paraesthesia and measurable weakness.[1]

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

The diagnosis is established by the history and physical examination, along with the findings of electro-physiologic studies and imaging.

Imaging

– with high-resolution neuro-ultrasonography, demonstration of changes in the size and position of the ulnar nerve at the elbow (also of changes in the echo texture of the nerve)

– magnetic resonance neurography (MRN) enables the visualization of structural changes of the ulnar nerve and its environment [4]

X-rays can be used to look for degenerative changes of the cervical spine and elbow, as well as bony compression from spurs or previous fractures. In establishing diagnosis, neurophysiological studies are helpful and should be done if surgery is planned, in order to document preoperative baseline. Ulnar nerve velocity of <50 m/s at the elbow is considered positive for cubital tunnel syndrome. [18]

Tinel’s signs are also used in the diagnostic procedure. These are also used in the diagnosis of tarsal tunnel syndrome.[19]

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

McGowan Score, Louisiana State University Medical Center Score, Bishop Score, and Medical Research Council grade, and Northwick Park Questionnaire are a few outcome measures that have been used.[21] Quick Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand questionnaire and the Short Form-12 can also be use. [22]

Examination[edit | edit source]

Tests used to confirm the diagnosis of cubital tunnel syndrome are those linking the ulnar neuropathy and the elbow. These tests should evoke provocative signs as a reaction to confirm this syndrome such as: elbow flexion reproducing symptoms, positive Tinel’s sign tested at the elbow or a sign of instability, for example the snapping of the ulnar nerve over the medial epicondyle with elbow flexion.[5]

The Elbow Flexion Test: Typically performed bilaterally with the shoulder in full external rotation and the elbow actively held in maximal flexion with wrist extension for one minute. A positive test is reproduction of numbness and tingling in the ulnar distribution on the involved side. Specificity (0.99) Sensitivity (0.75). [23]

When maximal elbow flexion is effectuated, symptoms are produced because the cubital tunnel volume is reduced by approximately 55% which causes an increase in neural pressure on the ulnar nerve. Some studies state that additional components such as wrist extension and wrist flexion or sustained maximal elbow flexion for up to three minutes can be included. These studies also state that quicker signs of a positive test are more indicative of a true diagnosis of cubital tunnel syndrome. The test is positive when pain is felt at the medial side of the elbow and numbness and tingling in the ulnar distribution on the involved side. This test has a high positive predictive value (0.97), which indicates a high probability of cubital tunnel syndrome if positive. (CTSII page)

The Pressure Provocative Test: The clinician applies pressure at the ulnar nerve at the cubital tunnel with the UE positioned as in the elbow flexion test for 30 seconds. Sensitivity (0.91).[24]

Tinel Sign: Reproduction of tingling and numbness into the 4th and 5th digits with tapping of the ulnar nerve at the cubital tunnel. Specificity (0.98), Sensitivity (0.70).[23]

The clinician will proceed with percussions (tapping) on the ulnar nerve as it passes through the cubital tunnel after the ulnar groove posterior of the medial epicondyle of the humerus is located. The number of percussions may vary depending on the research, but four to six taps should be sufficient to obtain symptoms. A positive test is the reproduction of tingling and numbness in the ulnar nerve distribution on the involved side. Cautions must be taken in the interpretation of the test because it has been found positive in 24% of asymptomatic subjects and it could be negative for those in the advanced stage of the diagnosis due to the fact that the nerve is no longer regenerating. (CTSII page)

The “scratch collapse” test: To perform the scratch collapse test, the patient’s skin is lightly scratched by the examiner over the area of nerve compression while the patient performs resisted bilateral shoulder external rotation. A brief loss of muscle resistance will be elicited if the patient has allodynia due to the compression neuropathy. Sensitivity for the scratch collapse was 69% compared with 54% and 46% for Tinel test and elbow flexion compression test, respectively. Of all tests for cubital tunnel, Tinel test had the highest negative predictive value (98%).[1]

Medical Management

[edit | edit source]

| [25] |

Operative Management: Indications for surgical intervention include failure of conservative treatment and an electrodiagnostic test of less than 39 meters per second across the elbow.[23] Several surgical techniques have been advocated for cubital tunnel syndrome. Techniques include: simple decompression, submuscular anterior transposition, and subcutaneous anterior ulnar transposition. Results found no difference in motor nerve-conduction velocities or clinical outcome scores between simple decompression and ulnar nerve transposition. [21]

Surgery is indicated in case of:

● progressive symptoms,

● sensorimotor deficits,

● lack of clinical and electro-neurographic improvement

● worsening of the objective findings on follow up several weeks after the initial visit.

Decompression is the mostly performed as surgical treatment. [4]

A recent study from 2014 investigated whether fascia wrapping would be a good surgical method and it found good results. Fascia wrapping is a type of sub-facial trans-positioning. This method provides better immobilization and requires less dissection than a sub-fascial transposition. All surgical treatments have disadvantages and advantages. It depends on the surgeon which method will be used. [2]

Simple decompression: A 6- to 10-cm incision is made along the course of the ulnar nerve between the medial epicondyle and the olecranon. Care should be taken to avoid the branches of the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve. Osbourne’s ligament is released as are the FCU superficial and deep fascia. It has been shown to be successful in treating cubital tunnel syndrome. Data suggests that in situ decompression is a reliable treatment with a low failure rate, and anterior trans-positioning can be used to treat those patients with recurrent symptoms.

There are three types of anterior transposition techniques that are named in relation to the flexor-pronator mass:

o Subcutaneous (above)

o Intermuscular (within)

o Sub-muscular (below)

Subcutaneous trans-positioning is another common surgical treatment for cubital tunnel syndrome. Its goal is to move the ulnar nerve anterior to the elbow axis of flexion, decreasing the tension on the nerve.

Intramuscular trans-positioning is another technique performed in combination with anterior trans-positioning of the nerve. Proponents of this technique believe that this places the nerve in a straighter line across the elbow joint. Opponents argue that scarring of the nerve can be caused, which serves as the bed for the transposed nerve. The procedure is similar to the subcutaneous trans-positioning; however a groove is created in the flexor-pronator muscle mass to serve as a tract into which the nerve is transposed.

Sub-muscular trans-positioning: Some surgeons prefer to place the nerve complete beneath the flexor-pronator mass. The branches of the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve are identified and protected. The ulnar nerve is identified and decompressed as in subcutaneous trans-positioning.

Medial epicondylectomy: It’s described in the treatment of ulnar nerve palsy.[1] Geutjens et al. have found limited evidence that shows that the medial anterior epicondylectomy offers a significantly better pain score than the ulnar nerve transposition in the treatment of cubital tunnel syndrome at long-term follow-up.[26]

Endoscopic decompression: It is the decompression of the ulnar nerve at the elbow. All techniques used a small 15-mm to 35-mm incision located over the ulnar nerve at the condylar groove. The variations rely on different techniques of retraction of subcutaneous tissues for visualization of the nerve.

Cubital tunnel syndrome is a common nerve compression with a variety of treatment options. Multiple surgical options exist that have been shown to ease symptoms. Selection of a surgical approach is based on the etiology of nerve compression, anatomic variations, and the surgeon’s experience. With careful protection of the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve and careful complete decompression of the nerve around the elbow, with or without transposition, good results can be obtained.[1]

Physical Therapy Management

[edit | edit source]

Initial goal of the conservative treatment for cubital tunnel syndrome is to control and decrease paraesthesia and pain. When the symptoms are mild and aggravating activities can be identified, the first step is eliminating those pain provocative activities. When symptoms occur in a wider range of activities which also possibly include work, therapy becomes more complex and can consist of activity modifications, splinting and rest. With this combination, pain and paraesthesia become more controllable.

The therapy begins with education about the development of the symptoms and how certain activities can have an influence on these symptoms. The therapist begins with explaining the origin of the ulnar nerve and how it is orientated in one’s body. This makes it easier to explain how certain movements can provoke pain such as stretching or compressing the nerve when collaterally tilting the head or abducting, depressing or external rotating the shoulder, supinating the forearm or extending the wrist. The therapist has to teach the patient to be able to analyse these movements during everyday activities and to make sure that provoking movements are not being made repetitively, which could cause aggravation of the symptoms. For many patients this could mean a lifelong management.[5]

Other studies show that the effect of rigid night splinting for a time period of three months combined with activity modification seems to be a successful. It has been proven that prolonged elbow flexion (static or repetitive) brings strain on the ulnar nerve and it increases extraneural and intraneural pressure in the cubital tunnel. The lowest value of these pressures is at an elbow position of 40o-50o of flexion. It has also been proven that pressures are significantly higher in full flexion or extension of the elbow. Splinting is meant to alleviate symptoms and prevent the progressive dysfunction of nerves. [22]

Non-operative Management: Non-operative management has been shown to have at least a 50% success rate with low-stage ulnar irritation. Nonsurgical treatment should be tried for at least 3 months before surgical intervention, especially in mild cases.[18] Non-operative management may include a 4-6 week period of immobilization with the elbow splinted at 45 degrees flexion and full supination. It has been recommended that athletes have active rest from sports. Modalities may be used to treat inflammation. Return to throwing is allowed at 4-6 weeks following absence of symptoms with any daily activities or exercise and return to full ROM and strength.[22] It also includes soft elbow pads, joint mobilizations, neural flossing and neural gliding, exercise. (CTSII page)

There is some low level evidence (case report ) that has utilized nerve-gliding techniques, segmental joint manipulation and a home program consisting of nerve gliding and light free weight exercises and was able to achieve positive outcomes. [27]

Beside education of the patient, immobilizing the elbow by the use of splints can reduce swelling and can help to identify the location of nerve irritation. Splinting the elbow in an appropriate way allows the nerve and the surrounding structures to rest and have relief from traction and compression. This method of therapy can be combined with the usage of local steroid injections which cause relief of pain and swelling. Though steroid injections can have positive effects, therapist has to keep in mind that this treatment can have complications such as scarring and atrophy.[5]

Night splinting has long been considered as an essential conservative treatment for cubital tunnel syndrome, but there are two issues that should bear consideration: the ability of the splint to maintain the elbow at the ideal position of 40-50 degrees of flexion and patient compliance with night splinting.[22]

Lund and Amadio point out that in their opinion, avoiding symptom provoking activities can be the most important issue in the therapy of cubital tunnel syndrome. This might also be the most expensive component as the patient may require assistance at home and in the case when during work the symptoms aggravate, it is also not possible for the patient to continue working. Patients are more desperate for a solution and they expect that medical professionals should come up with a fast and effective solution to their problems. This is a big challenge for professionals, as the recovery period of nerves is in some cases unpredictable.

Applying ice can also be a solution for reducing pain and swelling, which can be combined with gently applied active range of motion exercises. Patients should know that it’s not recommended to apply ice for longer than 60 minutes.

Ultrasound therapy is also an option but only in the case when used properly and with caution as it is also shown to cause further nerve damage when used on inappropriate intensity. This can slow down the speed of recovery.

Active range of motion exercises should be initiated within range of comfort, which means up to the point where the patient still does not experience any pain when moving. Stretching can be applied within tolerance and only after the level of pain has decreased.[5]

Differential diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Differential diagnosis should include cervical radiculopathy, thoracic outlet syndrome; MCL (UCL) insufficiency, tophaceous gout, and calcium pyrophosphate dehydrate crystal deposition.[22]

Cubital tunnel syndrome can be often misdiagnosed as C7 syndrome or other circulatory disturbance for example Raynaud's disease or polyneuropathy. [4]

The symptoms of cubital tunnel syndrome may be viewed as another condition and are similar to those associated with thoracic outlet syndrome, a C8 Nerve root entrapment, a double-crush syndrome, or a tumor. [14]

• Cervical Radiculopathy C8-T1: Motor and sensory deficits in a dermatome pattern including 4th-5th digits. It’s associated with weakness of the intrinsic muscles of the hand, and associated with painful and often limited cervical range of motion.

• Thoracic Outlet Syndrome: Compression of the structures of the brachial plexus which probably leads to pain, paraesthesia, and weakness in arm, shoulder, and neck.

• UCL Insufficiency: Laxity of the UCL can lead to excessive or abnormal movement of structures in or around the cubital tunnel which creates new sites of compression.

• Pancoast Tumor: Abnormal growth of tissue on the apex of the lung causing compression of the lower trunk of the brachial plexus.

These diagnoses present similarity to cubital tunnel with pain, paraesthesia, and potential weakness; nevertheless, symptoms specific to each diagnosis allow the specialist to rule out the doppelganger and rule in cubital tunnel syndrome. Examples of such symptoms are limited cervical motion and paraesthesia in other areas outside the ulnar nerve distribution. It is important for clinicians to correctly identify this diagnosis early due to the fact that, studies have shown an 88% improvement rate when treated within one year of onset as opposed to 67% improvement if treated after one year. (CTSII page)

Patients who suffer from cervical radiculopathy feel pain which initiates from the roots of the nerve and radiates to the upper back and the arm. When the upper trunk is affected (roots C5-6), patients experience pain when their arm is in an elevated in a hand-on-head position and creates slack in the brachial plexus. When it comes to patients with cubital tunnel syndrome, extension of the elbow and adduction of the arm would cause the most slacks and thus cause the most relief.[5]

Key Research[edit | edit source]

Zlowodzki and Chan[21]

Meta-Analysis of four RCT comparing simple decompression with anterior ulnar nerve transpostions. There were no significant differences between simple decompression and anterior transposition in terms of the clinical scores in those studies (standard mean difference in effect size = -0.04 [95% CI = -0.36 to 0.28], p = 0.81. Authors did not find significant heterogeneity across the studies. Two reports presented postoperative motor nerve conduction vlocities; they showed no significant difference between the the procedures. Conclusion: Data suggests that simple decompression is a reasonable alternative to anterior transposition for surgical management of ulnar nerve compression at the elbow.

Resources

[edit | edit source]

Journal Hand Microsurgery

Journal Hand Therapy

Journal Hand Surgery

Case Report[edit | edit source]

Coppieters and Bartholomeeusen[27]

The objective was to discuss the diagnosis and treatment of a patient with cubital tunnel syndrome and to illustrate novel treatment modalities for the ulnar nerve and its surrounding structures and target tissues. The patient was a 17 year old female with traumatic onset of cubital tunnel syndrome. She had pain around the elbow and paresthesia in the ulnar nerve distribution. Electrodiagnostic tests were negative. Segmental cervicothoracic motion dysfunctions were presentwhich were regarded as contributing factors hindering natural recovery. Six treatments included nerve-gliding techniques, segmental joint manipulation, and a home program of nerve gliding and light free-weight exercises. Substantial improvement was recorded on both the impairment and functional level. Symptoms did not recur within 10-month follow-up period. Pain and disability had completely resolved.

Bruce, Wasielewski and Hawke[14]

The patient was a 21-year-old male collegiate wrestler diagnosed with cubital tunnel syndrome. He was diagnosed with cubital tunnel syndrome after 6 weeks of increasing disability and dysfunction. He was treated conservatively for 3 months without resolution of the symptoms. Surgical treatment then involved a subcutaneous ulnar nerve transposition performed to decompress the cubital tunnel. Following surgery, the athlete participated in an aggressive rehabilitation program to restore function and strength to the elbow and adjacent joints. He was cleared for full unrestricted activity 15 days following surgery and returned to varsity athletic competition in one month. Their literature review found no reported cases of cubital tunnel syndrome in wrestlers. Cubital tunnel syndrome is usually seen in throwing athletes and results from either acute trauma or repetitive activities. The athletic trainer should consider cubital tunnel syndrome as a possible pathology for nonthrowing athletes when presented with associated signs and symptoms. [14]

Clinical Bottom Line[edit | edit source]

Despite the significant amount of literature devoted to the diagnosis and treatment of cubital tunnel syndrome, optimal treatment often requires two very simple components of treatment - time and rest. While surgical intervention can greatly ease symptoms, successful lifelong management of cubital tunnel syndrome also demands education and a dedicated effort at activity modification. Hopefully, with better environmental work conditions and early detection by the medical community, can the expenses involved, the time spent in rehabilitation, and most importantly the pain and debility these patients experience decrease with the help of the patient and employer, and the medical management team.[5]

Recent Related Research (from Pubmed)[edit | edit source]

Failed to load RSS feed from http://eutils.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/erss.cgi?rss_guid=1tUjNYI-_9Js-9CLZ61f-RfYmnSd5DpJiCYwauPMSVUmHW1ga8|charset=UTF-8|short|max=10: Error parsing XML for RSS

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Palmer BA, Hughes TB. Cubital Tunnel Syndrome. J Hand Surg. 2010; 35(1): 153–163.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Han HH, Kang HW, Lee JL, Jung S. Fascia Wrapping Technique: A Modified Method for the Treatment of Cubital Tunnel Syndrome. The Scientific World Journal. 2014; Article ID 482702, 6 pages. doi:10.1155/2014/482702

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Cutts S. Cubital tunnel syndrome. Postgrad Med J. 2007 Jan; 83(975): 28–31.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 Assmus H, Antoniadis G, Bischoff C. Carpal and cubital tunnel and other, rarer nerve compression syndromes. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2015 Jan 5;112(1-2):14-25; quiz 26.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 5.8 Lund AT, Amadio PC. Treatment of cubital tunnel syndrome: perspectives for the therapist. J Hand Ther. 2006 Apr-Jun;19(2):170-8.

- ↑ Rinkel WD, Schreuders TA, Koes BW, Huisstede BM. Current evidence for effectiveness of interventions for cubital tunnel syndrome, radial tunnel syndrome, instability, or bursitis of the elbow: a systematic review. Clin J Pain. 2013 Dec;29(12):1087-96.

- ↑ Feindel W, Stratford J. Cubital tunnel compression in tardy ulnar nerve palsy. Can Med Assoc J. 1958;78:351.

- ↑ Osborne GV. The surgical treatment of tardy ulnar neuritis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1957;39B:782.

- ↑ Tetro AM, Pichora DR. Cubital tunnel syndrome and the painful upper extremity. Hand Clin. 1996;12(4):665-677.

- ↑ Wheeless CR. Cubital tunnel syndrome. http://www.wheelessonline.com/ortho/cubital_tunnel_syndrome. Updated June 5, 2010. Accessed November 1, 2010.

- ↑ Lee ML, Rosenwasser MP. Chronic elbow instability. Orthop Coin North Am. 1999;30:81-89.

- ↑ Aldridge JW, Bruno RJ, Strauch RJ, Rosenwasser MP. Nerve entrapment in athletes. Clin Sports Med. 2001;20:95-122.

- ↑ Uscetin I, Bingol D, Ozkaya O, Orman C, Akan M. Ulnar nerve compression at the elbow caused by the epitrochleoanconeus muscle: a case report and surgical approach. Turk Neurosurg. 2014; 24(2):266-71.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 Bruce SL, Wasielewski N, Hawke RL. Cubital tunnel syndrome in a collegiate wrestler: a case report. J Athl Train. 1997 Apr;32(2):151-4.

- ↑ Sebelski CA. Current concepts of orthopaedic physical therapy. The Elbow: physical therapy management utilizing current evidence.

- ↑ Houston Methodist Orthopedics &amp;amp;amp;amp; Sports Medicine: A Patient's Guide to Cubital Tunnel Syndrome. http://www.methodistorthopedics.com/Cubital-Tunnel-Syndrome

- ↑ Wolgi MA. Ohttp://www.drwolgin.com/Pages/CubitalTunnelSyndr.aspx

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Wojewnik B, Bindra R. Cubital tunnel syndrome - Review of current literature on causes, diagnosis and treatment. J Hand Microsurg. 2009; 1(2):76-81.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Qing C, Zhang J, Wu S, Ling Z, Wang S, Li H, Li H. Clinical classification and treatment of cubital tunnel syndrome. Exp Ther Med. 2014 Nov;8(5):1365-1370.

- ↑ Watanabe M, Arita S, Hashizume H, Honda M, Nishida K, Ozaki T. Multiple regression analysis for grading and prognosis of cubital tunnel syndrome: assessment of Akahori's classification. Acta Med Okayama. 2013;67(1):35-44.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Zlowodzki M, Chan S, Bhandari M, Kalliamen L, Schubert W. Anterior transpositin compared with simple decompressin for treatment of cubital tunnel syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:2591-8. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "Zlowodzki" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 22.4 Shah CM, Calfee RP, Gelberman RH, CA Goldfarb. Outcomes of Rigid Night Splinting and Activity Modification in the Treatment of Cubital Tunnel Syndrome. J Hand Surg. 2013; 38(6): 1125–1130.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 Novak CB, Lee GW, Mackinnon SE, Lay L. Provocative testing for cubital tunnel syndrome. J Hand Surg Am. 1994 Sep;19(5):817-20.

- ↑ Novak

- ↑ reimerhoffman. Endoscopic Cubital Tunnel Syndrome. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qttiyxBP0uM [last accessed 22/03/13]

- ↑ Geutjens GG, Langstaff RJ, Smith NJ, Jefferson D, Howell CJ, Barton NJ. Medial epicondylectomy or ulnar-nerve transposition for ulnar neuropathy at the elbow? J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1996 Sep;78(5):777-9.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Coppieters MW, Bartholomeeusen KE, Stappaerts KH. Incorporating nerve-gliding techniques in the conservative treatment of cubital tunnel syndrome. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2004 Nov-Dec;27(9):560-8.

[[1]]