The use of exercise for the management of individuals with Ankylosing Spondylitis (AS)

Top Contributors - Elliot Brandon, Thomas Payne, Tom Potter, Kim Jackson, Mathew Gee, Vidya Acharya, Bruno Serra and Cindy John-Chu

This article or area is currently under construction and may only be partially complete. Please come back soon to see the finished work! (11/10/2023)

AS ROM and Flexibility exercise for Biological Outcomes[edit | edit source]

A recent retrospective study, observed that a significant number of patients with AS had visited centres for alternative therapies, suggesting that they are not satisfied with the current conventional approach of AS management [1]. Due to the broad impact of AS on various lifestyle factors, including pain and particularly quality of life, combined with the absence of a universally effective intervention, innovation in AS treatment is necessary. Recently, there has been a focus on alternative methods beyond generic exercise programmes and medication.

In this section, the focus of treatment will be exercise that aims to improve ROM and flexibility in those with AS and identify the outcomes of its implementation.

The first intervention which has been highlighted recently as being efficacious in the outcome measures associated with AS is Yoga.

A 2023 study by Singh et al.[2] focused on tele-yoga’s impact on AS patients amidst the covid pandemic. From the study of one hundred and twenty AS patients who were assigned to either the yoga intervention group (YG) or the control group (CG), they identified that the three-month Tele-Yoga intervention improved disease activity and quality of life in patients with ankylosing spondylitis compared with the control group. This positive trend associated with Yoga in AS is consistent in the broader literature. Singh et al.[1] also observed a 37.5% improvement in the sit-and-reach test of AS patients after nine days of integrated approach to yoga therapy intervention. This test examines the shortening of hamstrings and lumbar hyperextension, and with AS patients commonly reporting stiffness and pain of the lower back with AS patients commonly reporting stiffness and pain in the lower back, it shows how the improvement identified in the study can aid the presentation of AS. They concluded that the yoga intervention had an improvement in the flexibility and the functional status of patients [1].However, the retrospective design, small sample size, no randomisation, and no objective parameters in the study limits the external validity of the study but the results gathered still hold significant clinical relevance.

Another study by Singh et al.[3] focusing on patient perception of their condition found that the percentage of responses suggesting a high efficacy of Yoga was 85% (17/20). When analysed separately, the percentage of participants claiming pain reduction and improvement in their spinal flexibility with a yoga practice was 100% and 96%, respectively[3]. The researchers concluded that ‘The results of the pilot study suggested that the yoga module is feasible, acceptable, and easy to practice for AS patients. We recommend the yoga module to AS patients'[3]. Albeit these studies had relatively small sample sizes, which may reduce how generalisable and valid these conclusions are, their benefits, as identified by AS patients, provide promise for this intervention. However, more extensive comprehensive studies comparing this intervention with a control group are required to solidify these findings and allow Yoga to be globally prescribed to AS patients.

Another intervention which has a substantial base of research in AS is Pilates. Pilates has been determined in the literature as an effective and safe method for improving physical capacity in AS patients[5].

With AS, a set of key outcome measures are used to determine the extent of the condition. These measures are the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index (BASFI), Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Metrology Index (BASMI), Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI), Chest expansion and fingertip-to-floor (FTF) test. In a yearlong study looking at the effects that Pilates has on these measures from baseline. The researchers found that after the exercise intervention, improvements were observed in BASFI (77.51%), BASDAI (64.39%) and BASMI (58.95%) scores, FTF distance (71.92%), and chest expansion (88.74%)[6]. Roşu et al.[7] also identified a significant improvement in chest expansion, as well as clinical and functional AS-related parameters in patients performing Pilates-based exercise.

A final intervention which has enhancing flexibility and ROM at the forefront of its purpose is Tai Chi. For treating AS patients, Tai Chi has been widely advised for inclusion in rehabilitation programs due to it being a safe alternative type of exercise to reduce disease activity, improve spinal mobility and quality of life in patients with AS [8]. Another study identified that compared with standard exercise therapy, “Tai Chi spinal exercise” has an ideal effect in patients with Axial Spondyloarthritis (ax-SpA), which can more effectively relieve patient’s low back pain and improve spinal motor function, with shorter training time and better compliance [9]. This data shows that Tai Chi has beneficial outcomes in ax-SpA. With ax-SpA being the precursor to AS, it outlines the significant role interventions like Tai Chi can have in the preventative care of AS.

These findings further support the narrative that exercise such as Pilates, Tai Chi and Yoga, which focus on flexibility, balance and strength in tandem, have extensive clinical relevance and are worthy of greater research. The current studies of these interventions have yielded results that show not only physical benefits but also improvements in the psychosomatic element of the condition, and thus far, they have been highlighted as ‘less popular activities’ in the AS demographic [10]. With this significant evidence base, it raises the question as to whether these interventions should be promoted and implemented more in the care of those with AS than they are at present.

AS ROM and Flexibility for Psychological Outcomes[edit | edit source]

This following section further engages in active range of movement and flexibility exercise for the management of ankylosing spondylitis. However, there will be a deeper focus on the psychological elements of the various interventions, rather than the whole biopsychosocial model[11].

Yoga for patients with Ankylosing Spondylitis[edit | edit source]

The 2023 study performed by Singh et al[2] identified positive and significant improvements in Ankylosing Spondylitis disease activity and functional capacity from tele-yoga compared to ‘standard medical care’, which consisted of prescribed medication and physiotherapy management. However, not only did Singh et al[2] discover the positive trends in biological outcome measures, but improvements in psychological outcome measures were also observed following the three-month tele yoga programme. The AS-Quality of life tool evidenced significant increases within the tele-yoga group, effectively demonstrating the self-efficacy benefits that a yoga can have on an individual with AS[2]. The patient health questionnaire-4, used as a secondary outcome measure, included components assessing anxiety and depression levels[2], which are symptoms that Ma et al[12] discovered that AS patients are at higher risk of experiencing[12]. Both the control group and yoga group within Singh et al’s study[2] identified reductions in levels of anxiety and depression following intervention; however, the yoga group experienced significantly greater reductions than the control group, demonstrating the key emotional benefits of consistent exercise to manage one’s health conditions. External validity of the study should however be considered, due to the yoga being performed remotely, which limits the generalisability of the results to a group setting[2]. The significance of the yoga-group’s results throughout the study may appear exaggerated due to the contrasting interventions received between the two groups, with remote physiotherapy intervention and bi monthly check-ups received for the control groups[2].

Tai Chi for patients with Ankylosing Spondylitis[edit | edit source]

Previous literature supports the use of Tai Chi, an ancient Chinese exercise focusing on relaxation techniques, to improve disease activity and flexibility within a population with Ankylosing Spondylitis[13]. This study performed by Lee et al[13] involved 40 patients with AS to a Tai Chi group, receiving 60 minutes of home-based Tai Chi twice weekly for eight weeks, and a control group, receiving no intervention. A lack of change in outcome measures such as the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) and finger to floor distance (FFD) was identified, emphasising the importance of a form of intervention within the management of AS[13]. Another outcome measure used within Lee et al’s study[13] was the Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), aiming to measure the participants depressive symptomatology. The Tai Chi group demonstrated a score of -5.86 post-intervention, whilst the control group recorded a score of -2.12, a statistically significant difference[13]. However, the small intervention period, sample size and limited disclosed information regarding the randomisation process limits the external validity of the study, as well as the study being dated back to 2008[13].

Pilates for patients with Ankylosing Spondylitis[edit | edit source]

As previously discussed, Altan et al[5] deemed Pilates as an appropriate form of exercise for AS patients to improve physical functioning. The study used 55 participants with AS diagnoses, as per the Modified New York Criteria, exposing 30 participants to an hour Pilates exercise programme three times weekly for 12 weeks[5]. The other 25 participants received usual care in the means of exercise advice and their current medication[5]. Improvements deemed significant were identified over 24 weeks within the Pilates group in functional capacity, but little increase was observed within the Ankylosing Spondylitis Quality of Life questionnaire, with no significant difference between the usual care or Pilates group[5]. This demonstrates the physiological benefits that Pilates may have on an AS population, but how there may be alternative treatment modalities that more positively affect the psychological factors to health within an AS population[5]. However, this study was performed in 2012, more than 10 years ago, in which time Pilates may have developed as a treatment method for physiological and psychological outcomes within AS patients. This study also may have benefited from a longer period of intervention, as well as a larger sample size, limiting the risk of external validity and bias’[5]

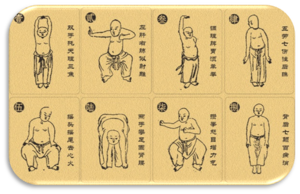

Baduanjin Qigong for patients with Ankylosing Spondylitis[edit | edit source]

Baduanjin Qigong is a traditional Chinese medicine that takes the form of exercise[14]. It dates back to over a thousand years ago, uses principles of Yin-Yang, whilst being a meditative movement prioritising exercising the body and the mind[14]. Baduanjin Qigong consists of eight varying movements, performed in a slow and controlled manner[14]. It targets balance, stretching the spine and limbs and increasing muscle strength[14]. Xie et al[14] performed a randomised controlled trial in 2019, exploring the benefits of Baduanjin Qigong exercise within the symptomatology of AS, over a 12-week intervention period. The study used a total of 60 patients, diagnosed with AS using the modified New York criteria, who were randomly assigned to the exercise group or no intervention group[14]. Following the 12-week intervention, the overall BASDAI score was not significantly lower than the group that received no treatment, as well as the BASFI, used as a secondary outcome measures[14]. Fatigue and the intensity and duration of morning stiffness were however significantly reduced post-intervention, compared to the control group, which are components of the BASDAI. Fatigue plays an important part within symptomology with AS, and is a recognised important symptom within an AS population, with patient strategies often provided to help manage one’s condition[15]. Fatigue has a significant effect on quality of life, and should be considered within the management of AS[15], which demonstrates the positive effects of Baduanjin Qigong on psychological factors and quality of life, due to the reductions in fatigue, despite not significantly improving disease activity scores[14]. However, the results from this study may not be repeatable due to the limited use of Baduanjin Qigong within the UK, which opens the door for other management strategies that are more easily accessible within the UK, like Yoga, Pilates and Tai Chi. The study also did not use a secondary follow-up period, which questions the validity and longevity of the results[14].

The best intervention for psychological factors in AS?[edit | edit source]

Research surrounding Yoga, Tai Chi, Pilates and Baduanjin Qigong have all demonstrated positive health trends in regard to improving health and biological-related outcome measures with Ankylosing Spondylitis[2][13][5][14]. However, all exercise modalities have varying levels of positive effects on the AS populations psychological health. Yoga saw significant improvements within levels of anxiety and depression in AS populations[2], Tai Chi prompted a significant reduction of depressive symptomatology within AS patients[13], but Baduanjin Qigong and Pilates observed marginal increases within fatigue, an indirect measure of psychological health anyway, and quality of life respectively, which were not deemed significant[5][14]. Yoga and Tai Chi are best advised for improvement within psychological outcome measures in AS populations, but the research used to determine this did include levels of bias and external validity, limiting its application to the AS population.

The use of aerobic exercise in AS[edit | edit source]

The progression of AS can lead to spinal restriction and deformity, functional impairment, and poor quality of life (Hsieh et al., 2016). AS often has manifestations in the cardiorespiratory system, as Mathieu et al. (2015)[17] report AS is considered to have a higher cardiovascular risk, with researchers observing an association between AS and increased cardiovascular mortality (Bhattad et al., 2022)[18]. Clinical features relating to the cardiorespiratory system may include:[3]

- Fibrosis of lung tissue

- Interstitial lung disease

- Aortic insufficiency

- AV node dysfunction

- Myocardial dysfunction

A Swedish study by Eriksson et al. (2017)[19] was conducted within a register-based setting, providing a nationwide and population-based sample which allowed the authors to assess and compare the incidence of cardiovascular events between patients with AS, RA and the general population. The results demonstrated that prevalent patients with AS are at a 30-50% increased risk of acute coronary, cerebrovascular and thromboembolic events compared with the general population.

In a cross-sectional study which evaluated aerobic capacity in patients with AS, Wong et al. (2017)[3] highlighted the relationship between cardiovascular mortality and low-level aerobic capacity. The authors concluded patients with AS had significantly reduced aerobic capacity. The deterioration of aerobic capacity in AS patients may be due to restrictive defects affecting respiratory function, as well as the involvement of inflammatory and sclerotic changes to costosternal, costovertebral and manubriosternal joints, producing adverse effects on rib cage mobility and chest expansion (Wong et al., 2017)[3]. As a result, pulmonary function tests in AS may show: • Reduced vital capacity (VC) • Reduced forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) • Reduced total lung capacity (TLC) • Increased residual volume (RV) • Increased functional residual capacity (FRC) (Hsieh et al., 2016).

Current guidelines on aerobic training in AS[edit | edit source]

Early identification and optimal cardiovascular risk management are essential to reduce the cardiovascular risk in AS patients (Heslinga et al., 2015)[21]. This is reflected in clinical guidelines, which recommend an individualised, structured exercise programme (NICE, 2017)[22]. Although, Ramiro et al. (2023)[23] report that the ASAS-EULAR 2022 recommendations highlight the ongoing debate regarding which exercises are best to perform. Specifically, NICE (2017)[22] guidelines encourage aerobic training as an adjuvant therapy as part of a wider exercise programme.

Current evidence on aerobic training in AS[edit | edit source]

Two systematic reviews have investigated the effect of aerobic exercise in people with AS, in comparison to standard physiotherapy and non-aerobic rehabilitative exercise.

The first is a study conducted by Verhoeven et al. (2019)[24] which was a systematic review and meta-analysis evaluating the impact of an aerobic fitness programme in adult AS patients, in comparison with non-aerobic physiotherapy rehabilitation in adult patients. The meta-analysis included 6 studies, including 300 patients. The intervention group included 148 patients who performed aerobic fitness exercises, whilst the control group included 152 patients who received physiotherapy rehabilitation (performing conventional exercise). All 6 studies were controlled studies, with 5 out of 6 being randomised. All studies were performed with walking or running exercises, and 2 studies included swimming exercises. The length of the intervention across the 6 studies was variable (4 studies performed interventions during 12 weeks, 1 study during 6 weeks, and 1 study during 3 weeks). Patient characteristics of both groups were similar in terms of age and sex ratio providing strong data.

The findings provided by Verhoeven et al. (2019) demonstrated that aerobic exercise did not provide more beneficial effects on AS compared to standard physiotherapy, either on disease activity (assessed by the BASDAI) or on physical function (assessed by the BASFI) and biological parameters (ESR and CRP). However, an important finding highlighted that there were improvements in cardiorespiratory fitness, aiding cardiovascular risk management. In addition to this, mental health was found to be improved by aerobic exercise, which can modify related disease activity.

A second, more recent systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted by Harpham, Harpham and Barker (2022)[25] which evaluated the effect of exercise training programmes with aerobic components on CRP, ESR and BASDAI in people with AS compared to non-aerobic rehabilitative control groups. A systematic search strategy elicited 13 included articles, with all studies reporting BASDAI measurements, 5 studies including CRP measurements and 4 studies including ESR measurements (10 were RCT’s, 2 were NRCT’s, 1 was a randomised pilot study). This review included 727 participants (exercise groups n=366, control groups n=361), with all studies including both male and female participants. Overall, 6 studies included aerobic exercises such as aerobic walking, Nordic walking, running, swimming and exergaming. 5 studies combined aerobic exercise (including treadmill/cycling/aerobic aquatic/fast walking/swimming/walking) with other exercise modalities (strengthening, flexibility and ROM). The remaining 2 studies used high-intensity interval training (HIIT). All studies compared the exercise groups with control groups receiving non-aerobic rehabilitative exercise comprised of usual care/treatment, no intervention and/or physiotherapy. The duration of exercise programmes ranged from 3 weeks to 3 months, with the most common duration being 12 weeks. Aerobic exercise intensity was monitored in 8 studies ranging from 55%-85% and 90%-95% (as interval protocol) maximum heart rate.

The results of this review produced BASDAI improvements of near clinical significance, along with CRP reductions, although similar improvements in ESR measurements were not found. This study provides the most specific evidence to date regarding the effects of aerobic exercise training on CRP and BASDAI in people with AS. However, the authors were unable to draw conclusions regarding the mode, duration and intensity of exercise due to methodological heterogeneity of available literature and overall insufficiency of evidence.

Bottom line

The findings of both systematic reviews corroborate with the ASAS-EULAR 2022 recommendations, which recognise that the heterogeneity and methodological limitations across studies on exercise and physiotherapy limit a definitive conclusion regarding which exercises are best to perform (Ramiro et al., 2023)[23]. However, given that cardiovascular disease is an associated comorbidity of AS, and that aerobic exercise has been evidenced to reduce cardiovascular risk factors in healthy populations, the findings of both systematic reviews by Verhoeven et al. (2019)[24] and Harpham et al. (2022)[25] indicate that aerobic exercise training should be considered as an adjuvant therapy for people with AS.

The use of exercise to manage social factors in AS:[edit | edit source]

Management of ankylosing spondylitis can be challenging, as in many cases patients with AS are still working, due to the early age of onset of the disease[26]. A longitudinal observational study found that AS correlated with reduced work productivity and employment, causing increased absenteeism and work disability[27]. The impact of AS also has a significant financial burden for healthcare systems and society[27]. This can have a knock-on effect on all aspects of an individual's life, and depression has been shown to correlate with employment and absenteeism[28]. Therefore, an intervention is needed to mitigate the social burden that AS has on individuals, and promote continuation of work, and overall quality of life.

Social support is vital during the management of AS. Research has shown that as individuals social support decreases, there is an increase in loneliness and depression scores [29]. Therefore, interventions aiming to limit absence from work may help to improve the psychosocial aspects of an individual's life and improve adherence to exercise. All factors mentioned will provide a holistic approach to the patient’s care.

Group based exercise for patient with ankylosing spondylitis:[edit | edit source]

A meta-analysis by Lane et al, (2022)[30] investigated the effectiveness of group and home-based exercise on the psychological status of individuals with AS. Group-based exercise was superior to home-based exercise for improving depression, anxiety, and mental health outcomes. The component of supervision was the key difference between groups, however adherence to the home-based exercise plan may have been questioned, as depression has been identified as a risk factor for exercise non-adherence in individuals with spondyloarthritis [31]. Furthermore, individuals participating in group exercise were supervised by physiotherapists and psychiatrists, which may have exposed individuals to a greater level of management education. Despite the positive outcomes of this study, the long-term effects are unclear. This meta-analysis provides evidence that group exercise may be of benefit in the early phases of AS, to improve exercise adherence, and provide patients with an insight of the effects of exercise for their condition. This may improve outcomes in the long-term management of AS, however, further research is needed to understand which individuals would benefit from this intervention.

Combining home and workplace exercise for patients with ankylosing spondylitis:

A study was conducted by Lim and Cho, (2021) [32], who aimed to investigate the effects of combining a home and workplace exercise programme, on physical function, depression and work-related disability in AS patients. 52 patients were included and split between 3 groups. One group combined home-and-workplace exercise, one group just included home-exercise, and the other was a control group. A combination of stretching and muscle strengthening exercise, walking, deep breathing exercises and workout videos were used in the home-and-workplace combined exercise plan. The combined exercise programme showed significant improvements in spinal mobility, pulmonary function, and significantly lower absenteeism and work-related disability, than the other groups. Due to AS patients having a three times higher risk of work-related disability due to physical dysfunction and structural changes[32], this study provides a potential intervention to lower this risk, and the social burden of the disease. However, for some patients the environment may be too overwhelming, or their occupation may not be appropriate for this type of intervention. A quasi-experimental study was used; therefore, variables were not controlled which may affect the reliability of results. There is currently minimal research combining home-and-workplace exercise, particularly in AS, and the long-term effects are unclear. However, progressively combining exercise with work may empower patients to correlate the improved physical function with attending their occupation and improved work-related outcomes.

ESCAPE PAIN exercise group:[edit | edit source]

In the UK, there is a national group exercise rehabilitation programme for individuals with arthritic pain. The programme “ESCAPE PAIN” is used to educate, perform exercise, and provide management techniques for individuals with pain. One of the programmes focuses on back pain, and a pilot study found that ESPACE-pain for backs significantly improves outcomes in musculoskeletal health, function, and mental wellbeing for individuals with lower back pain, whilst remaining in line with NICE guidelines[33]. Whilst this exercise group isn’t specific for ankylosing spondylitis, the implications for practice and effectiveness of outcomes provide a structured programme to educate individuals on the importance of exercise, whilst implementing the biopsychosocial approach. This also limits the financial burden on the NHS and society as less staff will be required to manage the group. Despite the benefits of ESCAPE pain, it has yet to be fully implemented in every trust in the UK. Physiotherapists should determine which patients may be appropriate for the exercise group, as this can massively impact a patient's physical, psychological, and social health.

Support groups:[edit | edit source]

The Spondylitis Association of America provides an online support group for individuals with Ankylosing spondylitis. This provides individuals with a sense of community, whilst also being able to discuss management techniques, and share stories that others may relate to. This can empower patients to come together who have experienced similar experiences, and to feel less isolated within their condition. Conversations with individuals who have had positive outcomes can improve adherence and allow patients to gain an insight into their potential.

There is very limited research investigating the use of support groups for Ankylosing Spondylitis. However, a study conducted by Barlow, et al, (1993)[34] found that individuals with AS, who were involved in a self-help group, had an increased frequency of exercise, greater satisfaction with available support, and a greater health locus of control. Physical improvements were also found over a 6-month period. Whilst this study is old, this provides evidence that individuals can experience an improved locus of control, empowering patients with AS to exercise more, and improve adhere to exercise. This can be identified by the secondary physiological improvements in patients in the self-help group.

With the growing rates of technology, this is an area that needs to be utilised. Patients will have the availability of constant support, which is of great importance when managing a long-term condition. Outcomes have shown to improve social and physiological markers in patients with AS, therefore further research is needed to validate the use of self-help groups in patients with AS. This will reduce the financial burden on the NHS and health care systems, whilst improving overall outcomes for patients.

The use of Hydrotherapy in Ankylosing Spondylitis[edit | edit source]

Hydrotherapy is the therapeutic application of water in a variety of ways. Hydrotherapy techniques apply a form of stress to the cells that influences their metabolic function, regulates their environment, and provides an opportunity for the body’s natural healing processes to take place (Doughty and Wahler, 2020)[36].

Balneotherapy - Stanger bath / therapy[edit | edit source]

Stanger baths / therapy, use heated water in combernation with low frequency currents or glavanic currentts, which passes thorough metal rods submeresed in the water.

A randomised control trial completed by Gurcay et al, (2008)[37], 58 patients with a diagnosis of Ankylosing Spondylitis . The patients were divided into two groups. Group one recived an exercise program and Stanger Baths, with the second group only reciving an exercise program.

The rults of this study showed that both groups that recived treatment had significant imporvments to no treatment. Group 1 showed greater reults in BASMI, BASFI, BASDAI, and ASQoL.. The imidate effects after treatment showed imporved spinal mobility, functional capacity, disease activity, and quality of life. The study found that short term it was benificial how ever more research was needed, which presuably is due to a smal sample size and the time the study was completed.

Balneotherapy - Spa therapy[edit | edit source]

Spa therapy is similar to Stanger bath Therapy however there is NO low frequency currents. Spa therapy is a hot water bath, without exercise. Francon and Forestier, (2009)[38] completed a review on SPA therapy in rheumatology. It was found that Spa therapy, or hot-water balneology, could be a suggested treatment method for AS as well as other arthritic conditions.

A narrative review on balneotherapy in chronic inflammatory rheumatic diseases completed by Cozzi et al, (2018[39]) was found to be satisfactory. Although according to Cozzi et al, (2018)[39] review they found that Balneotherapy was the most effective in patients with predominant axial involvement, such as with Ankylosing Spondylitis and that the RCTs found significant clinical improvement after long-term evaluation.

To round up balneotherapy /Spa therapy Ciprian et al, (2011)[40] found thatthe combination of spa therapy and rehabilitation exercise caused a clear, long-term clinical improvement in AS patients who were being treated with medication

Effects of Hydrotherapy[edit | edit source]

A systematic review and meta-Analys completed by Liang et al, (2019)[41] evaluating the efficacy of water therapy for disease activity, functional capacity, spinal mobility, and pain in patients with Ankylosing Spondylitis.

Analysis demonstrated that Hydrotherapy had a significant effect on disease activity and pain, however not on spinal mobility, or functional capacity in patients with Ankylosing Spondylitis. Liang et al, (2019)[41] says that Hydrotherapy can benefit patients with Ankylosing Spondylitis by reducing disease activity and alleviating pain. Due to its analgesic effect both during and after treatment, Hydrotherapy remains an alternative for patients with Ankylosing Spondylitis when land-based therapy is not well tolerated.

Effectiveness of hydrotherapy

A systematic review completed Medrado et al, (2022)[42] on Effectiveness of Hydrotherapy exercise.The primary outcome of this study were pain, disease activity, and physical function. A total of 5254 studies were identified, and nine articles were included, totalling 604 participants.

The results by Medrado et al,(2022)[42] found that when regarding pain, two studies showed that hydrotherapy exercise was superior to home exercise. One study showed that disease activity was significantly improved in the hydrotherapy group compared to the land-based exercise and the control groups (no exercise). Two studies reported that treatment which involed hydrotherapy exercises was able to improve physical function. Hydrotherapy exercise has been found to be effective in treating pain, disease activity, and physical function in individuals with inflammatory arthritis.

Summary of Hydrotherapy

Hydrotherapy apears to be bennificial for those with Ankylosing Spondylitis, in conjunction with Land based exercise. Hydrotherapy is reported to help relive pain, improve physical function and appear to reduce disease activity. However more research is need to confirm theses reults and to determain if Hydrotherapy is most benificail to those with Ankylosing Spondylitis.

References:[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Singh J, Tekur P, Metri KG, Mohanty S, Singh A, Nagaratna R. Potential role of yoga in the management of ankylosing spondylitis: A retrospective study. Annals of Neurosciences. 2021 Jan;28(1-2):74-8.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 2.9 Singh, J., Metri, K., Tekur, P., Mohanty, S., Singh, A. and Raghuram, N. (2023). Tele-yoga in the management of ankylosing spondylitis amidst COVID pandemic: A prospective randomized controlled trial. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice, [online] 50, p.101672. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctcp.2022.101672.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 Wong, M.L., Anderson, R.G., Garcia, K., Housmann, E.M., McHale, E., Goldberger, G.S. and Cahalin, L.P. (2017) The effect of inspiratory muscle training on respiratory variables in a patient with ankylosing spondylitis: A case report. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice, 33(10), 805-814

- ↑ Google.com. (2023). Avertissement de redirection. [online] Available at: https://www.google.com/url?sa=i&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.yogabasics.com%2Flearn%2Fashtanga [Accessed 30 May 2023].

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 5.8 Altan, L., Korkmaz, N., Dizdar, M. and Yurtkuran, M. (2011). Effect of Pilates training on people with ankylosing spondylitis. Rheumatology International, 32(7), pp.2093–2099. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-011-1932-9.

- ↑ Rodríguez-López, E.S., Garnacho-Garnacho, V.E., Guodemar-Pérez, J., García-Fernández, P. and Ruiz-López, M. (2019). One Year of Pilates Training for Ankylosing Spondylitis: A Pilot Study. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 25(10), pp.1054–1061. doi:https://doi.org/10.1089/acm.2018.0405.

- ↑ Roşu, M.O., Ţopa, I., Chirieac, R. and Ancuta, C. (2013). Effects of Pilates, McKenzie and Heckscher training on disease activity, spinal motility and pulmonary function in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a randomized controlled trial. Rheumatology International, 34(3), pp.367–372. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-013-2869-y.

- ↑ Cetin, S., Calik, B., Ayan, A. and Kabul, E. (2020). The effectiveness of 10-Tai Chi movements in patients with ankylosing spondylitis receiving anti-tumor necrosis factor α therapy: A randomized controlled trial. European Journal of Integrative Medicine, [online] 39, p.101208. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eujim.2020.101208.

- ↑ Ma, C., Qu, K., Wen, B., Zhang, Q., Gu, W., Liu, X., Shao, P., Shi, Y. and Wang, B. (2020). Clinical effect of ‘Tai Chi spinal exercise’ on spinal motor function in patients with axial spondyloarthritis. Int J Clin Exp Med, [online] 13(2), pp.673–681. Available at: https://e-century.us/files/ijcem/13/2/ijcem0103082.pdf [Accessed 18 May 2023].

- ↑ Brophy, S., Davies, H., Dennis, M.S., Cooksey, R., Husain, M.J., Irvine, E. and Siebert, S. (2013). Fatigue in Ankylosing Spondylitis: Treatment Should Focus on Pain Management. Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism, 42(4), pp.361–367. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semarthrit.2012.06.002.

- ↑ ENGEL, G. L. The clinical application of the biopsychosocial model. The Journal of Medicine and Philosophy: A Forum for Bioethics and Philosophy of Medicine, 1981. Oxford University Press, 101-124.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 MA, T., GENG, Y. & LI, P. 2022. Depression in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Rheumatology & Autoimmunity, 2, 69-75.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 13.6 13.7 LEE, E.-N., KIM, Y.-H., CHUNG, W. T. & LEE, M. S. 2008. Tai chi for disease activity and flexibility in patients with ankylosing spondylitis—a controlled clinical trial. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 5, 457-462.

- ↑ 14.00 14.01 14.02 14.03 14.04 14.05 14.06 14.07 14.08 14.09 14.10 XIE, Y., GUO, F., LU, Y., GUO, Y., WEI, G., LU, L., JI, W. & QIAN, X. 2019. A 12-week Baduanjin Qigong exercise improves symptoms of ankylosing spondylitis: a randomized controlled trial. Complementary therapies in clinical practice, 36, 113-119.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 MISSAOUI, B. & REVEL, M. Fatigue in ankylosing spondylitis. Annales de réadaptation et de médecine physique, 2006. Elsevier, 389-391.

- ↑ Google, (2019). What is Health Qi Gong? – JI HONG TAI CHI & QI GONG MISSISSAUGA. [online] Available at: https://www.taichi.ca/2019/07/08/what-is-health-qi-gong/.

- ↑ Mathieu, S., Pereira, B. and Soubrier, M. (2015) Cardiovascular events in ankylosing spondylitis: An updated meta-analysis. Arthritis and Rheumatism, 44(5), 551-555.

- ↑ Bhattad, P.B., Kulkarni, M., Patel, P.D. and Roumia, M. (2022) Cardiovascular Morbidity in Ankylosing Spondylitis: A Focus on Inflammatory Cardiac Disease. Cureus, 14(6), 1-6.

- ↑ Eriksson, J.K., Jacobsson, L., Bengtsson, K. and Askling, J. (2017) Is ankylosing spondylitis a risk factor for cardiovascular disease, and how do these risks compare with those in rheumatoid arthritis? Ann Rheum Dis, 76(2), 364-370.

- ↑ www.everydayhealth.com. (2020) 9 Smart Exercises For People With Ankylosing Spondylitis. [online]. Available at: www.everydayhealth.com/hs/ankylosing-spondylitis-treatment-management/pictures/smart-exercises/. [Accessed: 29 May, 2023].

- ↑ Heslinga, S.C., Van den Oever, I.A., Van Sijl, A.M., Peters, M.J., Van der Horst-Bruinsma, I.E., Smulders, Y.M. and Nurmohamed, M.T. (2015) Cardiovascular risk management in patients with active Ankylosing Spondylitis: a detailed evaluation. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 16(80), 1-8.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). (2017) Spondyloarthritis in over 16s: diagnosis and management. NICE, [online]. Available at: Spondyloarthritis in over 16s: diagnosis and management (nice.org.uk). [Accessed: 16 May, 2023].

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Ramiro, S., Nikiphorou, E., Sepriano, A. et al. (2023) ASAS-EULAR recommendations for the management of axial spondyloarthritis: 2022 update. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 82(1), 19-34.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Verhoeven, F., Guillot, X., Prati, C., Mougin, F., Tordi, T., Demougeot, C. and Wendling, D. (2019) Aerobic exercise for axial spondyloarthritis - its effects on disease activity and function as compared to standard physiotherapy: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. International Journal of Rheumatic Diseases, 22(2), 234-241

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Harpham, C., Harpham, Q.K. and Barker, A.R. (2022) The effect of exercise training programs with aerobic components on C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate and self-assessed disease activity in people with ankylosing spondylitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Rheumatic Diseases, 25(6), 635-649.

- ↑ Regnaux, J.-P., Davergne, T., Palazzo, C., Roren, A., Rannou, F., Boutron, I. and Lefevre-Colau, M.-M. (2019). Exercise programmes for ankylosing spondylitis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, CD011321(10).

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Boonen, A., Brinkhuizen, T., Landewé, R., van der Heijde, D. and Severens, J.L. (2010). Impact of ankylosing spondylitis on sick leave, presenteeism and unpaid productivity, and estimation of the societal cost. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 69(6), pp.1123–1128. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/ard.2009.116764.

- ↑ Healey, E., Haywood, K., Jordan, K., Garratt, A. and Packham, J. (2010). Impact of ankylosing spondylitis on work in patients across the UK. Scandinavian Journal of Rheumatology, 40(1), pp.34–40. doi:https://doi.org/10.3109/03009742.2010.487838

- ↑ Öksüz, E., Cinar, F.I., Cinar, M., Tekgoz, E. and Yilmaz, S. (2018). AB0841 Assessment of relationship between loneliness, perceived social support, depression and medication adherence in ankylosing spondylitis patients. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, [online] 77(Suppl 2), pp.1548–1549. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-eular.5873.

- ↑ Lane, B., McCullagh, R., Cardoso, J.R. and McVeigh, J.G. (2022). The effectiveness of group and home‐based exercise on psychological status in people with ankylosing spondylitis: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Musculoskeletal Care, 20(4).

- ↑ McDonald, M.T., Siebert, S., Coulter, E.H., McDonald, D.A. and Paul, L. (2019). Level of adherence to prescribed exercise in spondyloarthritis and factors affecting this adherence: a systematic review. Rheumatology International, [online] 39(2), pp.187–201.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Lim, J.M. and Cho, O.-H. (2021). Effects of Home-and-Workplace Combined Exercise for Patients with Ankylosing Spondylitis. Asian Nursing Research, 15(3), pp.181–188..

- ↑ ESCAPE-pain for backs: An evaluation of a 12-month pilot. (2020). [online] Health Innovation Network. Available at: https://escape-pain.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/Evaluation_of_the_ESCAPE-pain_for_backs_pilot_-1.pdf.

- ↑ Barlow, J.H., Macey, S.J. and Struthers, G.R. (1993). Health locus of control, self-help and treatment adherence in relation to ankylosing spondylitis patients. Patient Education and Counseling, 20(2-3), pp.153–166.

- ↑ https://embed.widencdn.net/img/veritas/dbrydqymna/1200x675px/water-aerobic-class.webp

- ↑ Doughty , J. and Wahler , V. (2020). Hydrotherapy - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics. [online] www.sciencedirect.com. Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/medicine-and-dentistry/hydrotherapy.

- ↑ Gurcay, E., Yuzer, S., Eksioglu, E., Bal, A. and Cakci, A. (2008). Stanger bath therapy for ankylosing spondylitis: illusion or reality? Clinical Rheumatology, 27(7), pp.913–917. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-008-0873-5.

- ↑ Françon, A. and Forestier, R. (2009). [Spa therapy in rheumatology. Indications based on the clinical guidelines of the French National Authority for health and the European League Against Rheumatism, and the results of 19 randomized clinical trials]. Bulletin De l’Academie Nationale De Medecine, [online] 193(6), pp.1345–1356; discussion 1356-1358. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20120164/ [Accessed 25 May 2023].

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Cozzi, F., Ciprian, L., Carrara, M., Galozzi, P., Zanatta, E., Scanu, A., Sfriso, P. and Punzi, L. (2018). Balneotherapy in chronic inflammatory rheumatic diseases—a narrative review. International Journal of Biometeorology, 62(12), pp.2065–2071. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00484-018-1618-z.

- ↑ Ciprian, L., Lo Nigro, A., Rizzo, M., Gava, A., Ramonda, R., Punzi, L. and Cozzi, F. (2011). The effects of combined spa therapy and rehabilitation on patients with ankylosing spondylitis being treated with TNF inhibitors. Rheumatology International, 33(1), pp.241–245. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-011-2147-9.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Liang, Z., Fu, C., Zhang, Q., Xiong, F., Peng, L., Chen, L., He, C. and Wei, Q. (2019). Effects of water therapy on disease activity, functional capacity, spinal mobility and severity of pain in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Disability and Rehabilitation, pp.1–8. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2019.1645218.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Medrado, L.N., Mendonça, M.L.M., Budib, M.B., Oliveira-Junior, S.A. and Martinez, P.F. (2022). Effectiveness of aquatic exercise in the treatment of inflammatory arthritis: systematic review. Rheumatology International. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-022-05145-w.