Pituitary Gland Tumors

Original Editor - Syeda Bushra Zehra Zaidi

Top Contributors - Syeda Bushra Zehra Zaidi, Lucinda hampton and Kapil Narale

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Pituitary Gland: The human pituitary gland, also known as the hypophysis, is a small, bean-shaped organ situated within the sella turcica or hypophysial fossa. This concave structure is located in the upper part of the sphenoid bone at the base of the brain. The gland is effectively shielded and safeguarded by the surrounding bony structure of the sella.[1]

Pituitary Gland Tumors: A pituitary gland tumor (a subset of brain tumors), also called a pituitary adenoma, is an abnormal growth in the pituitary gland located at the base of the brain. This gland controls vital bodily functions by producing hormones regulating growth, metabolism, and reproduction. (a subset of brain tumors)

These tumors vary in behavior—some grow slowly and go unnoticed unless detected incidentally, while others grow rapidly and cause severe symptoms like hormone imbalances leading to conditions like acromegaly or Cushing's disease. Aggressive adenomas may invade nearby areas in the brain.[2]

Types of Pituitary Gland Tumors[edit | edit source]

Pituitary adenomas are categorized based on their size and functionality.

Classification Based On Size[edit | edit source]

Tumors smaller than 10 mm are called microadenomas, those equal to or larger than 10 mm are termed macroadenomas, and those with a diameter of 40 mm or more are classified as giant adenomas.[3]

Functional And Non Functional[edit | edit source]

Functional pituitary adenomas produce hormones, causing various hormonal imbalances and related symptoms like acromegaly or Cushing's disease. Non-functional adenomas, on the other hand, do not produce excess hormones. They may grow and cause symptoms due to their size or compression on nearby structures rather than hormone overproduction.[3]

Causes and Risk Factors[edit | edit source]

Genetic predispositions[edit | edit source]

In pituitary adenomas contribute significantly to their development. While many adenomas occur sporadically without a known cause, certain genetic conditions and mutations increase the risk of adenoma formation. For instance:

- Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia Type 1 (MEN1): This hereditary condition arises from mutations in the MEN1 gene, leading to increased susceptibility to various pituitary adenomas, including endocrine tumors.[4][5]

- Carney Complex: Another genetic disorder involving multiple endocrine tumors, caused by mutations in the PRKAR1A gene. Pituitary adenomas are among the tumors associated with this condition.[4]

- Familial Isolated Pituitary Adenomas (FIPA): In some families, multiple members develop pituitary adenomas without other associated conditions. Genetic studies have identified mutations in genes like AIP (Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Interacting Protein) in some cases.[6]

Hormonal Imbalances[edit | edit source]

Pituitary adenomas can disrupt hormone levels due to their location and the types of cells they affect within the pituitary gland. The disruption occurs because the pituitary gland plays a pivotal role in regulating various hormones in the body. Here's how these tumors can cause hormonal imbalances:

- Overproduction of Hormones: Some adenomas are hormone-secreting, leading to excessive production and release of specific hormones. For instance, prolactin-secreting adenomas cause hyperprolactinemia, leading to issues like irregular menstrual periods, infertility, and lactation outside pregnancy.[7]

- Underproduction of Hormones: In contrast, certain adenomas can prevent the pituitary gland from producing adequate amounts of hormones due to compression or damage to hormone-producing cells. This can result in hormone deficiencies, affecting various bodily functions.[7]

- Impact on Hormone Pathways: Adenomas might disrupt the intricate balance of hormones within the hypothalamic-pituitary axis, a system involving interactions between the hypothalamus, pituitary gland, and other endocrine organs. Disturbances in this axis can lead to imbalances in various hormones regulated by this system.[8]

These disruptions in hormone levels due to pituitary adenomas can result in a wide array of symptoms and conditions depending on the specific hormones affected. Hormonal imbalances caused by these tumors often necessitate careful diagnosis and treatment to restore hormonal equilibrium and manage associated symptoms.

Symptoms[edit | edit source]

Common Signs and Symptoms[edit | edit source]

- Mood disorders

- Sexual dysfunction

- Infertility

- Obesity

- Visual disturbances

Variations based on Tumor Type and Size[edit | edit source]

Tumor Type (Functional vs. Non-functional)[edit | edit source]

Functional Adenomas: These tumors produce hormones, leading to specific symptoms related to the excess hormone they secrete. For instance:

- Prolactinomas: Result in irregular menstrual periods, breast milk discharge (galactorrhea), and infertility in women, and reduced libido or erectile dysfunction in men.

- Growth Hormone-Secreting Adenomas: Cause acromegaly, characterized by enlarged hands, feet, facial changes, and increased sweating.

- ACTH-Secreting Adenomas: Lead to Cushing's disease, causing weight gain, high blood pressure, mood changes, and skin changes.[10]

Non-functional Adenomas: These tumors do not produce excess hormones but can cause symptoms due to their size and compression effects on surrounding tissues:

Pressure Symptoms: Such as headaches, vision changes (blurred or loss of peripheral vision), and other neurological symptoms due to compression of nearby structures.[11]

Tumor Size[edit | edit source]

- Microadenomas: These small tumors may not cause noticeable symptoms unless they produce excess hormones. They are often detected incidentally during imaging tests or postmortem examinations.

- Macroadenomas: Larger tumors can lead to more pronounced symptoms due to their size and pressure effects on nearby structures:

- Visual Disturbances: Macroadenomas can press on the optic nerves, causing visual changes like blurred vision or loss of peripheral vision.

- Headaches: Larger tumors may cause persistent or severe headaches due to increased pressure within the skull.

- Hormonal Imbalances: If a macroadenoma is functional, it can produce more significant hormonal disruptions compared to microadenomas, leading to distinct hormone-related symptoms.[12]

Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Imaging Studies[edit | edit source]

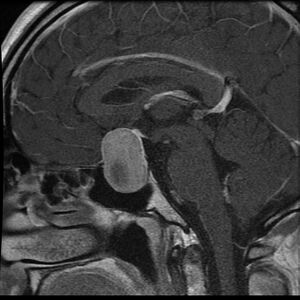

- MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging): This imaging technique provides detailed images of the pituitary gland and surrounding structures. It helps in visualizing the size, location, and characteristics of the adenoma. Gadolinium-based contrast agents are often used to enhance the visualization of the tumor.

- CT (Computed Tomography) Scan: While not as sensitive as MRI for detecting pituitary adenomas, CT scans can still be used to assess the size and extent of the tumor. It's particularly useful in emergency situations or when MRI is contraindicated.[13][14]

Hormone Level Tests[edit | edit source]

- Blood Tests: Measurement of hormone levels in the blood helps identify hormone-secreting adenomas. Tests include assessing levels of hormones such as prolactin, growth hormone, ACTH, TSH, LH, FSH, and others based on suspected hormone imbalances.[13]

- Dynamic Function Tests: These tests involve stimulating or suppressing hormone production to evaluate the gland's function. Examples include the dexamethasone suppression test for ACTH-secreting adenomas or the oral glucose tolerance test for growth hormone-secreting adenomas.

Visual Field Testing[edit | edit source]

If there are suspected visual disturbances due to compression of the optic nerves, visual field tests are conducted to assess any visual deficits.[15]

Treatment Options[edit | edit source]

Medications[edit | edit source]

- Dopamine Agonists: These medications, such as bromocriptine or cabergoline, are commonly used to treat prolactin-secreting adenomas (prolactinomas). They help reduce prolactin levels and shrink the tumor, alleviating symptoms like menstrual irregularities, infertility, and milk discharge.[16]

- Somatostatin Analogs: For growth hormone-secreting adenomas causing acromegaly, medications like octreotide or lanreotide can be prescribed to lower growth hormone levels and reduce tumor size.[13]

- Corticosteroids: In cases of adrenal insufficiency due to ACTH-secreting adenomas (Cushing's disease), corticosteroid replacement therapy may be necessary to manage hormone deficiencies after surgery.[16]

Surgery[edit | edit source]

- Transsphenoidal Surgery: This is the most common approach for removing pituitary adenomas. Surgeons access the pituitary gland through the nose or upper lip, using specialized instruments to reach and remove the tumor. It's considered minimally invasive and often results in shorter hospital stays and faster recovery times.[17]

- Endoscopic Surgery: A variation of transsphenoidal surgery, endoscopic techniques use a tiny camera to provide enhanced visualization. This method may allow for better tumor removal with improved precision.[18]

Radiation Therapy[edit | edit source]

- Conventional Radiation Therapy: Used when surgery isn't an option or in cases where the tumor persists after surgery. It involves delivering targeted radiation to the tumor over several sessions to halt its growth or shrink it further.[19]

- Stereotactic Radiosurgery: This technique delivers a highly focused and precise dose of radiation to the tumor while minimizing exposure to surrounding healthy tissue. It's often used for small residual tumors or as an alternative when surgery isn't feasible.[19]

The choice of treatment depends on various factors, including the tumor size, type, location, hormone secretion, and the individual's overall health. Often, a multidisciplinary approach involving endocrinologists, neurosurgeons, and radiation oncologists is necessary to tailor the treatment plan to the patient's specific needs.

Each treatment option has its benefits and potential risks, which should be thoroughly discussed with healthcare professionals to determine the most suitable course of action for managing pituitary adenomas

Reference[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Ray R. Evaluation of Size of Normal Adult Pituitary Gland on Magnetic Resonance Imaging (Doctoral dissertation, Rajiv Gandhi University of Health Sciences (India)).

- ↑ Asa SL. Tumors of the pituitary gland. American registry of pathology; 1998.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Solari D, Pivonello R, Caggiano C, Guadagno E, Chiaramonte C, Miccoli G, Cavallo LM, De Caro MD, Colao A, Cappabianca P. Pituitary adenomas: what are the key features? What are the current treatments? Where is the future taking us?. World Neurosurgery. 2019 Jul 1;127:695-709.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Schernthaner-Reiter MH, Trivellin G, Stratakis CA. MEN1, MEN4, and carney complex: pathology and molecular genetics. Neuroendocrinology. 2016 Jan 9;103(1):18-31.

- ↑ Wu Y, Gao L, Guo X, Wang Z, Lian W, Deng K, Lu L, Xing B, Zhu H. Pituitary adenomas in patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1: a single-center experience in China. Pituitary. 2019 Apr 15;22:113-23.

- ↑ Chahal HS, Chapple JP, Frohman LA, Grossman AB, Korbonits M. Clinical, genetic and molecular characterization of patients with familial isolated pituitary adenomas (FIPA). Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2010 Jul 1;21(7):419-27.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Pinkson S. General pituitary disorders. Physician Assistant Clinics. 2017 Jan 1;2(1):107-22.

- ↑ Tanase C, Ogrezeanu I, Badiu C. Molecular pathology of pituitary adenomas. Elsevier; 2011 Nov 16.

- ↑ Asa SL, Ezzat S. The pathogenesis of pituitary tumours. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2002 Nov 1;2(11):836-49.

- ↑ Arafah BM, Nasrallah MP. Pituitary tumors: pathophysiology, clinical manifestations and management. Endocrine-related cancer. 2001 Dec 1;8(4):287-305.

- ↑ Greenman Y, Stern N. Non-functioning pituitary adenomas. Best practice & research Clinical endocrinology & metabolism. 2009 Oct 1;23(5):625-38.

- ↑ Greenman Y, Stern N. Non-functioning pituitary adenomas. Best practice & research Clinical endocrinology & metabolism. 2009 Oct 1;23(5):625-38.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Chanson P, Salenave S. Diagnosis and treatment of pituitary adenomas. Minerva endocrinologica. 2004 Dec 1;29(4):241-75.

- ↑ Bonneville JF. Magnetic resonance imaging of pituitary tumors. Imaging in Endocrine Disorders. 2016;45:97-120.

- ↑ Anderson D, Faber P, Marcovitz S, Hardy J, Lorenzetti D. Pituitary tumors and the ophthalmologist. Ophthalmology. 1983 Nov 1;90(11):1265-70.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Molitch ME. Diagnosis and treatment of pituitary adenomas: a review. Jama. 2017 Feb 7;317(5):516-24.

- ↑ Shou XF, Li SQ, Wang YF, Zhao Y, Jia PF, Zhou LF. Treatment of pituitary adenomas with a transsphenoidal approach. Neurosurgery. 2005 Feb 1;56(2):249-56.

- ↑ Cappabianca P, Cavallo LM, Solari D, Stagno V, Esposito F, de Angelis M. Endoscopic endonasal surgery for pituitary adenomas. World neurosurgery. 2014 Dec 1;82(6):S3-11.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Gheorghiu ML, Fleseriu M. Stereotactic radiation therapy in pituitary adenomas, is it better than conventional radiation therapy?. Acta Endocrinologica (Bucharest). 2017 Oct;13(4):476.