Infant Development in Supine

Original Editor - Pam Versfeld

Top Contributors - Stacy Schiurring and Jess Bell

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Time lying supine on a firm, flat surface is important because it is the first position that allows infants to independently interact with their environment and learn how to stabilise their head and trunk. This, in turn, enables them to use their vision, hands and feet to explore their social and physical environment. Treatment interventions and management should focus on encouraging infants with developmental delays to thrive during the early years of their life, as this period is critical for maximising their potential.[1]

This article describes infant motor development when lying supine on a firm, flat surface. In this article, development in supine is divided into four periods: (1) newborn infant, (2) infant from 1-2 months, (3) infant from 3-4 months and (4) infant from 5-6 months.

Supine Development in the Newborn Infant: 0-4 weeks[edit | edit source]

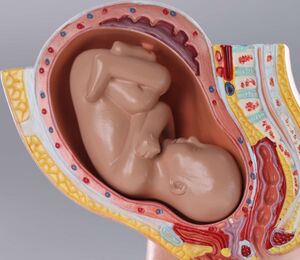

During the newborn period, infants are adapting to their new social and physical environment. The sensorimotor abilities they acquired while in the buoyant, fluid, intrauterine environment are harnessed and adapted to the new constraints on movement imposed by gravity and the surfaces they encounter.

- Their limbs have weight, and limb movement produces reactive forces and momentum - these need to be factored into the control of their movements

- When awake and alert on a firm surface, they can respond to visual and auditory events in the environment and actively produce spontaneous movements of the limbs

- Observation of and interaction with their surroundings create perception-action loops that are the basis for making the shift from spontaneous exploratory movements to intentional, goal-directed actions

Limb Movement Synergies at Birth[edit | edit source]

- The lower extremity synergy is characterised by intra-limb coupling of hip and knee flexion or extension

- The upper limb synergy combines shoulder and elbow extension with extension of the fingers and wrist

Over the next few months, as the infant explores different ways of interacting with the environment and the frontal motor areas of their brain become more active, the strong intra-limb coupling lessens. Movement is adapted to allow for effective interaction with the environment.[2]

Behavioural States and General Movements[edit | edit source]

When awake, infants shift between several different states. These states affect the organisation of their spontaneous movements.

- Alert but quiet state: minimal movement. The alert but quiet state is often associated with the infant's visual attention being focused on their hand, the face of a social partner or other interesting visual stimuli in the environment

- Alert and active state: bouts of vigorous, spontaneous limb movements

- Distressed state: movements are ongoing and very vigorous; limb jitters and trembling may be present

Einspieler et al.[3] describe the characteristics of the complex movements that involve the entire body observed in infants from 0-2 months as follows:

These writhing general movements "are characterised by a variable sequence of neck, arm, trunk, and leg movements. They wax and wane, varying in intensity, speed, and range of motion, and have a gradual onset and end. Rotations along the axis of the limbs and slight changes in the direction of movement make them appear fluent and elegant and create the impression of complexity and variability.” - Einspieler et al., 2008[3]

Newborn Head Posture and Movements[edit | edit source]

- Generally, newborns keep their head rotated to one side in supine,[4] and tend to have a preferred side (typically to the right)[5]

- Neck rotation continues to be associated with neck extension and lateral flexion to the contralateral side[4]

- Can turn the head to the midline and briefly sustain this position:

- with visual attention to an interesting person, object or event

- when actively moving limbs or distressed[6]

- Over the next few weeks, they develop the bilateral, antigravity neck muscle strength and the control needed to counteract the force of gravity and maintain their head in midline for longer periods

Visual Attention[edit | edit source]

- From the first few weeks, infants pay attention to interesting objects that come into their field of vision:

- when their head is supported in the midline, they will look at the face of a caregiver for extended periods; they will turn their head away when they need a break

- when their head is supported, they can move their head to bring their social partner's face into the centre of their visual field and can mirror facial expressions

- Visual attention is usually associated with the cessation of limb movements

- Infants engage in sustained visual regard of their own hands and tend to pay close attention to the hands of a caregiver

Newborn Rolling[edit | edit source]

Typical limb stiffness (muscle tone) in newborns allows head turning to initiate partial rolling into side-lying. This response may be due to the neonatal neck righting reflex.[4] It may also be because turning the neck shifts the infant’s weight laterally, which destabilises the trunk, "toppling" them over into side-lying.

Upper Extremity Posture and Movements[edit | edit source]

- During periods of relative quietening of movement:

- upper arms rest on the supporting surface close to the body, with the shoulders in slight external rotation, the elbows in flexion and the hands slightly open[4]

- Spontaneous movements of the upper limbs:

- bring the infant's hand into their visual field, and a period of quiet may ensue as the infant pays attention to their hand

- bring the infant's hands into contact with their face and / or hand-to-mouth

- Hand and finger movements:

- large range of motion (ROM) of the shoulder and elbows is seen, with the fingers opening when the elbow is extended and the fingers flexing with elbow flexion[7]

- spontaneous movements of the fingers include (1) grasping and hand opening, (2) pointing with the forefinger, (3) thumb to forefinger, and (4) simultaneous flexion of the forefinger and middle finger, and the ring and little finger

- infants are able to imitate a demonstration of one-, two- and three-finger extension patterns[8]

- palmer grasp reflex (response): when gentle pressure is applied to an infant's palm, the infant's fingers flex to hold the examiner's finger. The pressure applied to the palm produces traction on the tendons of the fingers, which encourages the infant to cling to the examiner's finger. The infant's thumb is not affected by this reflex.[9]

Lower Extremity Posture, Range of Motion and Kicking Actions[edit | edit source]

In infants born at full-term, hip and knee ROM is limited by lower extremity flexor muscle tightness and increased muscle tone, which results from the flexed posture assumed in the last weeks of intrauterine life. This hip extension restriction is referred to as neonatal hip flexion contracture.

- During periods of relative quietening of movement:

- hips are flexed, abducted and laterally (externally) rotated, and feet are lifted off the supporting surface

- knees cannot be fully extended; when passively extended, they recoil back to a more flexed position

- Newborn kicking actions are characterised by the following:

- decrease in hip flexion ROM and some knee extension

- ankle remains in dorsiflexion with toes in flexion

- after kicking, the infant returns to the more flexed resting position

Supine Development in the 1-2 Month Period[edit | edit source]

During the 1-2 month period, the infant is awake and alert for longer periods, increasingly responds to environmental sounds and sights, and gains more control of head and limb movements.

General and Fidgety Movements[edit | edit source]

General movements continue to be characterised by writhing movements that involve the head, trunk and extremities, but fidgety movements become increasingly present towards the end of this period.[10]

- Writhing movements are complex and involve the entire body in variable sequences

- Fidgety movements are "general, circular movements of small amplitude".[11] They are moderate speed with variable acceleration of the neck, trunk, and limbs in all directions:

- they may appear as early as six weeks after term, but usually occur from around 9 weeks until 16–20 weeks

- they fade when antigravity and intentional movements begin to dominate

- the presence and character of fidgety movements are good indicators of the integrity of the infant's nervous system[10]

Head Control and Neck Movements[edit | edit source]

At the beginning of this period, infants still tend to lie in supine:

- they lie with their head turned to one or the other side

- head rotation continues to be associated with some neck extension and lateral rotation

- head turning may also be associated with an asymmetrical tonic neck reflex (ATNR) posture

By the end of the 1-2 month period:

- infants are more inclined to hold their head in the midline

- they easily turn their head to scan and observe the environment and are able to combine neck rotation with extension of the head to look upwards

Infants tend to lie with their upper limbs abducted and extended, a position that helps to stabilise the trunk and provide a stable base for head movements and kicking.[4]

Infants can visually follow an object from the side to the midline and follow an object moving in a downward direction.

Upper Extremity Posture and Movements[edit | edit source]

During periods of relative quiet, the one-month-old infant adopts a variety of postures of the upper limbs:

- abduction of shoulders with upper arms resting on the support surface:

- allows the upper extremities to stabilise the trunk against movements of the head and lower extremities

- this strategy decreases towards the end of this period as infants begin to bring their hands into the midline[2]

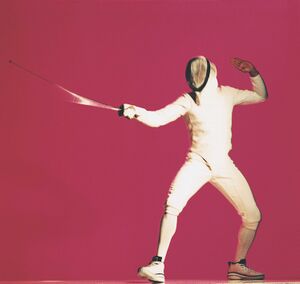

Head rotation may be associated with the fencing position (extension of the elbow on the side to which the infant has turned their head, and flexion of the elbow on the opposite side).

At the beginning of this period:

- infants produce large-range swiping movements of the upper extremities in supine, which are associated with elbow extension and finger extension

- during these movements, the hand comes close to the object but rarely makes contact

- over the coming weeks, the infant gains more control over reaching movements - they start to reach towards objects within easy reach with greater success[2]

- they bring their hand close to the toy and use small-range movements of the shoulder and elbow to explore different ways of touching and grasping the toy

By the end of this period:

- infants are better able to steady their head and trunk while reaching with the upper extremities

- they can bring their hand into contact with a toy and explore with their fingers

- this marks the beginning of the ability to stabilise their hand position in space while using independent finger movements to gather information about objects

- visual attention also improves and provides additional information about objects

Postural Sway and Stability[edit | edit source]

Exploratory movements allow the postural system to gather the sensory information needed to estimate the position of the body as a whole and explore the most effective strategies to maintain a stable posture.[12]

Lower Extremity Posture and Movements[edit | edit source]

- Supine posture during relative periods of calm: feet rest on the support surface with varying amounts of hip and knee flexion

- Infants at this stage still engage in extended periods of kicking: movement patterns include repeated single-leg kicking with alternate leg kicking and bilateral hip and knee flexion and extension

- Hip and knee movements are still coupled:

- ankles remain in dorsiflexion with intermittent flexion and extension of the toes

- plantar flexion ROM has increased

Lower Extremity Bridging[edit | edit source]

- From time to time, the infant pushes one or both feet down on the support surface

- Pushing down with one foot is associated with head and trunk extension and lateral weight shift

Pull-to-Sit [edit | edit source]

The infant's response to the pull-to-sit manoeuvre is often used as a test when assessing motor development. It provides a good measure of the infant's neck muscle strength and the development of effective anticipatory postural responses.

By the end of the 1-2 month period, infants have learned to anticipate being lifted and will participate in the pull-to-sit manoeuvre by engaging their neck and trunk flexor muscles, stiffening their upper limbs and flexing their hips. The head is held in line with the trunk as the shoulders are lifted.

Once in the upright position, the head is held erect, and the infant can lift their face to look at the examiner.

Supine Development in the 3-4 Month Period[edit | edit source]

- Infants at this stage spend more time in an alert, awake state, which allows for more time to observe, explore and interact with the social and physical environment

- They become aware of their ability to engage caregivers, are learning how to attract their attention, and engage in social interaction using smiles, facial mirroring (imitation) and vocalisation[13]

- They are better able to self-regulate their levels of arousal as they learn to self-soothe and turn away from visual events that they find unpleasant

- Fidgety movements can still be observed[10]

Head Control and Neck Movements[edit | edit source]

- An infant's ability to maintain their head in the midline becomes fully established, which allows them to visually focus on people and toys presented in the midline

- Infants now easily turn their head through full range of motion, and can keep their head in flexion without associated side flexion. Rotation of the neck does not affect the position of the extremities

- They are also able to rotate and extend their neck to look at an object to the side and above their head

- Flexion of the head on the neck also allows the infant to look down to bring objects that they are holding into the centre of their field of vision for detailed inspection (foveal vision)

Visual Convergence and Tracking[edit | edit source]

- Infants are now able to track an object moved from one side to the other across the midline

- Tracking upwards is also present, but tracking downward is less consistent

Being Lifted[edit | edit source]

Infants increasingly anticipate being lifted when they see their caregiver preparing to pick them up. The caregivers's intention is signalled by their hands moving towards the infant's chest who in turn starts to recruit their neck and trunk muscles in anticipation of being lifted.[14]

- As the infant's neck strength increases, caregivers provide less neck support while lifting the infant

- Infants tend to have improved control of neck lateral flexion and extension than flexion against gravity

- Turning infants as they are lifted allows them to maintain control of the position of their head

Pull-to-Sit[edit | edit source]

- Infants increasingly anticipate being lifted from supine into sitting when the caregiver grasps and pulls on their hands:

- infants flex their neck and trunk, recruit their upper extremity muscles in response to the traction on their hands, and lift the lower extremities off the support surface

- When tipped backwards from sitting, infants can flex their neck to control the position of their head as their torso is lowered to the support surface

Postural Stability[edit | edit source]

When supine on a firm, flat surface, infants are very active, with repeated bouts of kicking, reaching for toys within easy reach, and actively using their hands and feet to explore the surrounding surfaces and their bodies. They are very curious and turn their heads to look at interesting and novel events in the environment.

- This activity is important for strengthening the trunk and limb muscles. Moreover, infants with high activity levels of the upper extremities, as measured by full-day wearable sensors, have been shown to have higher cognitive, language and motor scores[15]

- This period also sees an increasing ability to stabilise the trunk when moving the extremities, which allows the infant more control to engage in intentional and goal-directed reaching and exploratory movements of the hands and feet

Upper Extremity Posture and Movements[edit | edit source]

During periods of relative quiet, 3-4-month-old infants adopt a variety of postures of the upper limbs, sometimes with their shoulders in abduction and their extremity held away from the torso, but frequently with the hands together in the midline.

Hands together in midline:

- infants will visually inspect their hands for long periods

- this visual attention is aided by the infant's ability to flex their head on their neck and, at the same time, look downwards to bring their hands into the centre of their field of vision for a clearer view

- reaching towards a toy presented in the midline is bilateral, with one hand usually making contact before the other

Lower Extremity Posture and Movements[edit | edit source]

3-4-month-old infants have acquired the ability to move their lower extremities in a variety of ways due to their ability to flex and extend their hips and knees in different combinations.

In supine, during periods of relative quiet:

- infants may lie with their hips and knees flexed, with their feet lifted off the support surface - this is associated with posterior pelvic tilt

- hip flexion and extension are associated with some hip abduction

By the end of this period:

- hip extension ROM increases

- hip abduction ROM in extension decreases

- crossing legs at the feet is frequently seen

Bridging[edit | edit source]

The infant will often put one or both feet flat on the support surface with their knees flexed:

- pushing down on the support surface with both feet does not yet result in lifting the buttocks up (bridging)

- pushing down with one foot leads to extension of the ipsilateral hip with forward rotation of the pelvis; this action may initiate rolling to the side

Kicking[edit | edit source]

- Periods of repeated unilateral and reciprocal kicking continue at this stage

- the trunk is held steady and is symmetrical during periods of active kicking

Foot Movements[edit | edit source]

- Infants bring their feet together and engage in exploratory ankle movement

- Isolated ankle dorsiflexion and plantar flexion movements are frequently seen

Rolling[edit | edit source]

- Rolling from supine to side-lying becomes more frequent

- Infants use a variety of patterns to initiate rolling

Supine Development in the 5-6 Month Period[edit | edit source]

- At this stage, an infant's behaviour and actions become more intentional and goal-oriented (e.g. using hands and feet to explore objects and surfaces)

- Infants become increasingly aware of their ability to initiate social encounters and know how to attract and maintain the attention of social partners[13]

- Infants are increasingly able to adapt postural alignment, stability and movements to achieve a desired goal

- Infants become more mobile as they learn to roll from supine to prone and start to use this mobility to move around on a supportive surface

Emerging Abilities During this Period[edit | edit source]

- Improved ability to steady the trunk when the limbs are moving

- Increasing hip and trunk flexor muscle strength, which allows the infant to lift both feet off the support surface in a sustained manner

- Posterior pelvic tilt is associated with bilateral hip flexion, which allows the infant to reach for their feet and bring one foot to their mouth

- Uncoupling of hip and knee flexion allows for increased ability to perform isolated movements of the lower extremity joints

- Increased control while reaching for objects

- Increasing ability to hold an object with one hand and explore its properties with the other

- Emerging tendency to bang and shake toys and pass them from one hand to the other

- Prominence of exploratory movements of the hands and feet

- Ability to actively initiate and control rolling from supine to side-lying and prone

Head and Trunk Stability[edit | edit source]

- At this stage, infants have full neck rotation ROM

- They can visually follow a moving object in all directions, including from one side to the other and across the midline

- Head-on-neck flexion is well established and allows the infant to watch their hands while reaching for or manually inspecting a toy held in midline above the chest

- They are able to keep their head and trunk steady when moving the extremities, which allows for more control of intentional upper extremity movements and holding

Lower Extremity Posture and Movements[edit | edit source]

In supine, during periods of relative quiet:

- infants lie with their feet resting on the support surface, particularly when engaged with a toy or observing the environment

- they often lie with both hips flexed, commonly with knee flexion. Hip flexion ROM increases with improving trunk muscle strength and control of posterior pelvic tilt

- they start to reach for and grab their feet

Kicking[edit | edit source]

- Infants continue to move their lower limbs vigorously, using a variety of patterns, including (1) reciprocal kicking movements, (2) bilateral hip and knee flexion, and (3) bilateral hip and knee extension

Bridging[edit | edit source]

- With both feet on the support surface, infants begin to lift their buttocks off the support surface (into a bridge)

Rolling[edit | edit source]

- Infants become progressively more adept at rolling from supine to prone

- They explore different options for initiating rolling

Atypical Development and Developmental Delay[edit | edit source]

Typical infant development occurs via an interaction between the development of the nervous system and various organ systems and stimulation from the infant's social and physical environment.[16] Infants who demonstrate atypical or developmental delay tend to be (1) less physically active, and (2) lack movement repetition. Therefore, they miss opportunities for motor learning and sensory integration.

To learn more about paediatric diagnoses which can cause developmental delays, please review the following Physiopedia Pages:

The management and treatment of developmental delay should be an interdisciplinary team effort. The team should include primary care providers, neurologists, developmental and behavioural paediatricians, speech and language therapists (pathologists), occupational therapists, physiotherapists, and nutritionists. Treatment strategies are usually multi-modal[17] and often require input from multiple medical and rehabilitation disciplines, with strong family support.

Resources[edit | edit source]

Optional Additional Reading:[edit | edit source]

- Dusing SC, Thacker LR, Stergiou N, Galloway JC. Early complexity supports development of motor behaviors in the first months of life. Developmental psychobiology. 2013 May;55(4):404-14.

- Einspieler C, Peharz R, Marschik PB. Fidgety movements–tiny in appearance, but huge in impact. Jornal de Pediatria. 2016 May;92:64-70.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Smythe T, Zuurmond M, Tann CJ, Gladstone M, Kuper H. Early intervention for children with developmental disabilities in low and middle-income countries–the case for action. International health. 2021 May;13(3):222-31.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Von Hofsten C. Developmental Changes in the Organization of Pre-reaching Movements. Developmental Psychology. 1984;20(3):378-88.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Einspieler C, Marschik PB, Prechtl HFR. Human motor behavior prenatal origin and early postnatal development. Journal of Psychology. 2008;216(3) 148-54.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Bly L. Motor Skills Acquisition in the First Year, 1994.

- ↑ Rönnqvist L, Hopkins B. Head position preference in the human newborn: a new look. Child Dev. 1998;69(1):13-23.

- ↑ Cornwell KS, Fitzgerald HE, Harris LJ. On the state‐dependent nature of infant head orientation. Infant Mental Health Journal. 1985;6(3):137-144.

- ↑ Von Hofsten C, Rönnqvist L. The structuring of neonatal arm movements. Child Dev. 1993;64(4):1046-57.

- ↑ Nagy E, Pal A, Orvos H. Learning to imitate individual finger movements by the human neonate. Dev Sci. 2014;17(6):841-57.

- ↑ Anekar AA, Bordoni B. Palmar Grasp Reflex. 2020.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Einspieler C, Peharz R, Marschik PB. Fidgety movements–tiny in appearance, but huge in impact. Jornal de Pediatria. 2016 May;92:64-70.

- ↑ Doroniewicz I, Ledwoń DJ, Affanasowicz A, Kieszczyńska K, Latos D, Matyja M, Mitas AW, Myśliwiec A. Writhing movement detection in newborns on the second and third day of life using pose-based feature machine learning classification. Sensors. 2020 Oct 22;20(21):5986.

- ↑ Dusing SC, Harbourne RT. Variability in postural control during infancy: implications for development, assessment, and intervention. Physical Therapy. 2010;90(12):1838–49.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Brazelton TB. Touchpoints Birth to Three, 2006.

- ↑ Reddy V, Markova G, Wallot S. Anticipatory adjustments to being picked up in infancy. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(6):e65289.

- ↑ Shida-Tokeshi J, Lane CJ, Trujillo-Priego IA, Deng W, Vanderbilt DL, Loeb GE, Smith BA. Relationships between full-day arm movement characteristics and developmental status in infants with typical development as they learn to reach: An observational study. Gates open research. 2018;2:17.

- ↑ Brown KA, Parikh S, Patel DR. Understanding basic concepts of developmental diagnosis in children. Translational pediatrics. 2020 Feb;9(Suppl 1):S9.

- ↑ Khan I, Leventhal BL. Developmental delay. 2020.