Guillain-Barré Case Study: David

Abstract[edit | edit source]

This case study follows the case of David Atkin, who was diagnosed with Guillain-Barré Syndrome (GBS) following a bacterial gastro-intestinal infection of Campylobacter Jejuni. GBS is an autoimmune disease characterized by bilateral progressive motor deficits beginning in the hands or feet. David had progressive loss of motor control and sensation primarily to the feet which led him to checking into the emergency department. Rapid progression of his symptoms occurred, affecting his respiratory muscles and leading to respiratory failure. David consequently had to be intubated and placed on a mechanical ventilator. Following the acute phase, the intervention plan focuses on aspects of mobility, strength, aerobic capacity, and balance to achieve his goals related to body structure, activity, and participation. This case provides a typical case presentation of GBS, in addition to possible assessment methods, outcome measures, and technological uses to treat this disease.

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Guillain-Barré Syndrome (GBS) is a rare autoimmune disease that affects the peripheral nervous system (PNS). The exact mechanism is unclear, but the majority of GBS cases are triggered following bacterial or viral infection[1]. GBS can also be triggered by trauma, surgery, cancer, or vaccination[2][3]. GBS has 3 subtypes, however the most common subtype is acute inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy, caused by an autoimmune reaction where the immune system targets and breaks down the myelin sheath surrounding peripheral nerves, therefore a disease of demyelination[4]. The first symptoms noticed are typically numbness, tingling, or pain (alone or in combination) beginning in the feet and ascending proximally towards the head. Over the course of days to weeks, there is onset of progressive muscle weakness in the extremities and potential paralysis[5]. Guillain-Barré Syndrome can also lead to weakening of the respiratory muscles and eventual respiratory failure[1]. Many complications can arise during the acute stage of GBS including: deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, heart attack, pneumonia, and infection. Death occurs in about 2.6% of all cases of GBS[6].

Signs and Symptoms[7][8][9][edit | edit source]

- Bilateral numbness, tingling, or pain (alone or in combination) that begins in the hands and feet

- Progressive bilateral weakness of the extremities

- Impaired gait and balance

- Weakness of facial muscles

- Difficulty with swallowing or speaking

- Double vision

- Severe pain that may worsen during the night

- Changes to bowel/bladder control

- Paralysis

- Respiratory failure

- Autonomic dysfunction (abnormal changes to heart rate and blood pressure)

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

- More common in men[10]

- Risk increases with age[10]

- 3,000 to 6,000 cases per year in the United States[11]

- Incidence of subtypes varies between countries[2]

Subtypes[edit | edit source]

There are several subtypes of GBS, each presenting differently and affecting different populations. In North America, the most common form of GBS is Acute Inflammatory Demyelinating Polyradiculoneuropathy (AIDP)[2]. AIDP is characterized by the presence of sensory symptoms, muscle weakness, involvement of cranial nerves, and autonomic dysregulation. The focus of this case study is on the AIDP subtype; the presentation follows the classic sensorimotor pattern of symptoms.

Prognosis[edit | edit source]

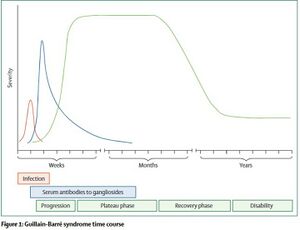

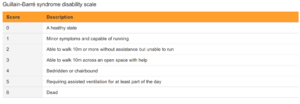

Symptom severity can vary and as such, the degree of recovery and the timeline also varies. Many patients have chronic symptoms and changes to their functional status following their bout with GBS. The Guillain-Barré Syndrome (GBS) Disability Scale is used to measure the degree of recovery[14]. Recovery can range from full recovery for some patients to significant functional impairment for others. The prognosis of GBS depends primarily on age of the patient and on the severity of symptoms two weeks after onset. Older individuals are more likely to have lasting effects following an episode of GBS.

The course of GBS includes progression of symptoms of days to weeks before reaching a plateau period where symptoms stabilize. The plateau period typically lasts weeks but in some cases may last months. Following that there is a gradual recovery where function returns, however, this can take months and many are left with some level of disability.[9]

Roughly 30% of GBS cases will lead to weakness of the respiratory muscles which may eventually lead to respiratory failure[15]. If this occurs, the patient will have to be intubated and placed on mechanical ventilation. Mechanical ventilation can lead to complications such as pneumonia which can affect negatively affect recovery.

Client Characteristics[edit | edit source]

Patient Profile[edit | edit source]

- Initials: D. A (David Atkin)

- Preferred Name: Dave

- Age: 35 years

- DOB: 12 June 1987

- Gender: Male

- Height: 172cm

- Weight: 90kgs

- Significant Presentation: Sudden onset of symmetrical bilateral acroparesthesia and paralysis in lower extremities. Patient presented with areflexia and flaccidity bilaterally on testing.

History of Present Illness[edit | edit source]

- Date of Admission: 30th March 2023

- Type of Admission: Self- referral. Patient woke up and was unable to move his lower limbs. Patient brought in an ambulance to Kingston General hospital (KGH).

- Initial Diagnosis: Acute inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (AIDP) a sub-type of Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS). The patient was admitted in KGH on 14th March 2023 with a gastrointestinal infection (caused by Campylobacter Jejuni[1]) which is one of the significant diagnostic indicators of GBS.

- Date of Onset: 30th March 2023

- Treatment to Date (20th April 2023): Intravenous immunoglobulin therapy and plasmapheresis, the previous PT and PTA worked on bed mobility.

- Present Status: Alert and oriented. Minimal regain of motor and sensory loss bilaterally on both extremities. (Note: On 15th April 2023, patient was transferred to ICU and intubated after acute bradycardia, bilateral facial paralysis and acute respiratory distress. Patient had shown progressive bilateral symmetrical sensory and motor loss in both upper and lower extremities.)

- Precautions / Contraindications: Patient may exhibit occasional orthostatic hypotension if they are assisted out of recumbent position.

Past Medical History[edit | edit source]

- Allergies: Peanuts and tree nuts

Medication[edit | edit source]

- Venus thromboembolic prophylactics to prevent Deep Vein Thrombosis and Pulmonary Embolism

- Amlodipine 5mg per day for hypertension

Health Habits[edit | edit source]

- Smokes one pack of cigarettes every day since the age of 30 years (5 pack-years), and reports drinking 1 beer (3 times a week)

Social History[edit | edit source]

- Works as a manager at a software development firm in Kingston

- The patient lives in a 2-story independent house that has 12 stairs with his wife and 2 daughters (aged 9 and 6)

Functional History[edit | edit source]

- Resistance training at GoodLife fitness twice a week.

- Was independent with BADLs and IADLs

- Fell once while skateboarding and fractured his left wrist in December 2019

Current Functional Status[edit | edit source]

- Has independent bed mobility

- Can maintain seated posture alone but needs assist x1 to transition from laying to sitting and assist x2 to stand

- Unable to ambulate due to balance impairments combined weakness in extremities

Examination Findings[edit | edit source]

Observation[edit | edit source]

The patient is alert and oriented - no lines or tubes present; currently lying in semi-reclined position. Patient appears to be in good spirits and expressed optimism for his recovery.

Mobility[edit | edit source]

- Bed mobility: independent to slide up, down, sideways, roll onto side

- Lie to sit: minimal Ax1

- Sit-to-stand: unable to stand on own requires max Ax2

- Transfers: moderate Ax2 required for pivot transfer

Personal Care/ADLs[edit | edit source]

- Assistance needed for dressing and bathing

- Currently utilizing a urinary catheter

- Independent to feed oneself

Gait[edit | edit source]

- Currently unable to ambulate due to lower extremity weakness

- Need fitting for gait aid when required

Range of Motion[edit | edit source]

| Muscle group | AROM | PROM | Muscle Group | AROM | PROM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All shoulder movements | WNL | WNL | Hip flexion | 45 | WNL | |

| All elbow movements | WNL | WNL | Hip extension | 10 | WNL | |

| All wrist movements | WNL | WNL | Hip adduction | WNL | WNL | |

| Hip abduction | WNL | WNL | ||||

| Knee extension | WNL | WNL | ||||

| Knee flexion | 100 | WNL | ||||

| Dorsiflexion | WNL | WNL | ||||

| Plantar flexion | WNL | WNL |

Muscle Strength[edit | edit source]

| Muscle group | Right | Left | Muscle Group | Right | Left | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All shoulder movements | 4 | 4 | Hip flexion | 3- | 3- | |

| Elbow flexion | 4- | 4- | Hip extension | 3- | 3- | |

| Elbow extension | 4 | 4 | Hip adduction | 4 | 4 | |

| Wrist flexion | 4- | 4- | Hip abduction | 3 | 3 | |

| Wrist extension | 4- | 4- | Knee extension | 3+ | 3+ | |

| Knee flexion | 3- | 3- | ||||

| Dorsiflexion | 3+ | 3+ | ||||

| Plantar flexion | 3+ | 3+ |

Balance[edit | edit source]

- Seated: patient can maintain a seated posture independently once positioned, with SBA

- Standing: unable to independently stand, requires max Ax2

Common Comorbidities[16][edit | edit source]

- Hypertension

- Diabetes

- Hyperlipidemia

- Stroke

- Lung Infection

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

- Functional Independence Measure (FIM)

- The FIM is a common outcome measure used to determine the ability to perform activities of daily living. It is made up of 18 individual items consisting of motor and cognitive functioning, that are scored from 1 (total assistance) to 7 (independent). Each item is added together to get an overall level of independence between 18-1126. The FIM is considered time-consuming but an easy-to-use, valid and reliable method that can be trusted in clinical settings to assess patients with various conditions.[17]

- 10-Meter Walk Test

- The 10-meter walk test is a useful tool to measure gait speed and functional mobility. The tool uses the amount of time a patient takes to walk 10 meters, to provide a speed in m/sec. This can be compared to normative data to determine risk of falls and if a gait aid is indicated. The 10-meter walk test is a common tool used by clinicians and is seen as reliable and valid for a number of neurological conditions[18].

- Medical Research Council Sumscore

- The Medical Research Council Sumscore is a common tool used to measure muscle strength. This tool considers six main muscle groups (bilaterally) and assesses their strength using a scale of 0-5. These six scores can then be added together to create a total sum ranging from 0 to 60[19]. It has shown to be a clinically useful tool for physiotherapists for neurological conditions. This tool has high intra-rate reliability, indicating it needs to be repeated by the same physiotherapist to assess change[20].

Clinical Hypothesis[edit | edit source]

Analysis Statement

35 y/o male admitted to Kingston General Hospital (KGH) via ambulance on March 30th, 2023, due to inability to move lower limbs after waking up. Pt presents with bilateral acroparesthesia and paralysis in lower extremities, with bilateral areflexia and flaccidity; diagnosed with acute inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (AIDP) - a sub-type of Guillain-Barre syndrome. Pt currently unable to ambulate due to impaired strength, sensation, and balance in lower extremities. This patient's prognosis tends to be positive with a variety of factors that favour his recovery including young age, previously being active, and a relatively high MRC Sumscore on initial assessment. However, the patient has several negative factors affecting his prognosis as well, these include having to take care of two daughters, being a current smoker, and an inability to ambulate. This patient would benefit from physiotherapy treatment focused on strengthening the lower extremities, improving balance, and increasing mobility.

Problem List[edit | edit source]

- Unable to care for two young daughters (participation in role as a father)

- Inability to ambulate (activity)

- Lower extremity weakness in all major muscle groups (body function)

Goals[edit | edit source]

Long-Term Goals

- To be able to pick up and hold daughters safely within the next 4 months

- To be able to walk independently with a 2WW to get to the bathroom within the next 3 months

- Gain the lower extremity strength to be able to perform 10 arm-supported squats within the next 2 months

Short-Term Goals

- To be able to maintain independently sitting balance for 10 minutes while reading and interacting with daughters in the next week

- Achieve a sit-to-stand and be able to stand with minimal support and a 2WW within the next 3 weeks.

- To be able to complete 10 repetitions of in-bed resistance exercises (glute bridge, quad-over-roll), twice a day within the next 2 weeks

Intervention[edit | edit source]

Treatment Plan

Though there is no known cure to Guillain-Barre syndrome, physiotherapists play an important role in the functional recovery of GBS patients. In the acute phase of recovery of GBS, the patient likely will not tolerate active movement due to a rapidly worsening condition. Thus, at this stage the physiotherapist may play more of an advisory role, educating the patient on the prevention of deep vein thrombosis (DVTs), pressure sores, and contractures [21]. However, 90% of GBS patients reach clinical nadir within 4 weeks, with aspects of functional recovery occurring thereafter [22]. This is where the primary focus of our intervention plan in David’s case. General goals of physical therapy treatment for GBS patients include optimal muscle use at tolerable pain levels, in addition to the use of supportive equipment to recover function to pre-illness levels (as much as possible) [21]. Various exercise programmes have been shown to improve physical outcomes in patients with GBS, such as functional mobility, cardiopulmonary function, isokinetic muscle strength, and reduced fatigue[23]. We are recommending David complete PT treatment anywhere from 3-5x per week for 1 hr, as a higher intensity program relative to lower intensity program may lead to significantly reduced disability in GBS patients [24]. However, it is crucial to note that exercise should not be done to fatigue in patients with GBS, as this may cause central fatigue, loss of strength, and delay recovery[21]. Lastly, considering pain is a common symptom of GBS and can be prevalent throughout rehabilitation, strategies such as transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), heat, and sensory desensitization techniques may be of aid in alleviating pain and improving tolerance to exercise[21]. However, the unique pain experiences of individuals with GBS leads to varied outcomes when using these techniques. To achieve David’s short- and long-term goals, treatment will focus on mobility, range of motion (ROM), strength, balance, and cardiorespiratory endurance. As a secondary benefit, these multiple types of activities help facilitate sensory stimulation and desensitization techniques, along with using fine and gross motor skills for movement re-education and pain reduction [21]. Along with the justification of each physical outcome as part of our program, we have included specific exercises with FITT (frequency, intensity, time, type) parameters as a possible course of treatment:

ROM

To prevent muscle atrophy and other negative effects of disuse, it is important to help David get moving as soon as he is able [21]. A natural progression of range of motion exercises begins with passive range of motion, following by active assisted range of motion (AAROM), then finally to active movements. Equipment such as a powder board or a hydrotherapy pool can facilitate movement while limiting work on anti-gravity muscles [21]. Additionally, David may use proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation (PNF) stretching to improve motor function and motor control [25]. Possible stretches David can do is a supine hip flexor stretch, supine figure 4 stretch, calf stretch, hamstring stretch, pec stretch, and elbow flexor stretch. These may be assisted by the physiotherapist, or the patient may use equipment such as a strap. Importantly, these stretches should not cause fatigue. Listed below are the FITT parameters to follow:

| Frequency | 3x/week (or daily) |

| Intensity | slight discomfort, but no pain |

| Type | static stretching, PNF stretching |

| Time | 30-60s |

Strengthening

When beginning a strength program with GBS, it is important to start slowly, with zero resistance and the inclusion of frequent rest breaks. Training should not be completed to fatigue; complaints of fatigue should not persist for >12-24 hours post session [21]. Strength training of the lower and upper extremity may increase functionality and quality of life in individuals with GBS [26]. In David’s case, strengthening should target the weakness observed in his lower extremities. Bed exercises may include isometrics (e.g., glute squeeze, quad squeeze, etc.), isotonic exercises (quad over roll, heel slides, glute bridges), and resistance band training (e.g., bicep curl, triceps extension, etc.). Once David achieves ambulation, strength training can progress to more functional movements for daily tasks (such as sit to stands and squatting) and achieving his personal goals (such as playing with his daughters).

| Frequqncy | 3x per week (daily if tolerated to promote movement) |

| Intesity | Never to fatigue |

| Type | Isokinetic and isometric |

| Time | Variable |

Aerobic Capacity

In addition to ROM and strengthening, other activities (such as aerobic capacity) can be beneficial for cardiovascular health and general conditioning [25]. The exercises vary, but may include an arm ergometer, cycling ergometer, walking. Cycling has been shown to elicit significant functional improvements in GBS patients [23]. Cardiorespiratory endurance will positively affect physical fitness and reduced fatigue, positively affecting all of David’s goals [25].

| Frequency | 3x/week |

| Intensity | Roughly 65% MHR or not exceeding 45% heart rate reserve[27]; 0 Watts- may choose to increase wattage as one progresses; Moderate RPE on BORG scale [21] |

| Type | Variable - Arm ergometer, cycling, walking |

| Time | 5-10 mins, up to 30 mins |

Balance

Balance is an integral part of everyday life for GBS patients and thus should be included within meaningful activities. David can practice balance with sitting exercises, such as reaching for objects like the TV remote or a glass of water across the table. Standing balance exercises may be out of reach currently, but David can progress to these in the future. In due time, these may include trying to change clothes, getting in and out of the shower/tub, and re-introduction to leisure activities with minimal to no assistance. Along with other physically demanding activities, it is paramount with balance (both sitting and standing) to ensure adequate rest breaks are taken to reduce the risk of falling [21].

| Frequency | 3x/week (daily if tolerated) |

| Intensity | Never to fatigue |

| Type | Sitting and Standing balance exercises |

| Time | Sitting: 30-60 seconds as tolerated. Standing: 5-30 seconds as tolerated. |

Transfers (Bed Mobility)

Transfers may be taught to maximize independence, help achieve David’s meaningful activities and ADLs, and prevent pressure sores in patients with GBS, particularly in the non-ambulatory phase of the condition. Some useful transfers to teach David include:

- Lying to sitting

- Sitting to standing

- Pivot transfer

| Frequency | 3x/day (if tolerated) |

| Intensity | Never to fatigue |

| Type | Lying to sitting, sitting to standing, and pivot transfer |

| Time | Throughout the day as necessary |

Innovative Technology: Virtual Motor Rehabilitation System

A key clinical feature of GBS is motor disturbances and muscle weakness that can become persistent and progressive. There has been evidence that traditional motor rehabilitation programs have been beneficial at the onset of this condition to limit the complications of paralysis and with ongoing persistent motor impairments.[28] However, these rehabilitation programs are often tedious and monotonous, leading to decreased adherence.

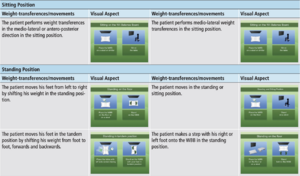

In order to combat the low adherence, a novel virtual motor rehabilitation system has been implemented in two single case studies to assess the effectiveness as an alternative treatment method. An Active Balance Rehabilitation (ABAR) system has been developed for to assist with balance and gait disorders, which utilizes different Virtual Environments to emphasize weight transferences and specific movements that can target symptoms of GBS while addressing other motor impairments.

The characteristics of the ABAR system include:

- A flexible system for the recovery of postural control and for reducing fractures and the risks of falls.

- A suitable system that improves the patient’s motivation and treatment adherence.

- A reinforcement system that allows the results obtained in each session to be monitored and the appropriate action taken.

- A robust system that is able to make a good recovery in parameters such as balance, postural control, muscle tone, and stability in the standing/sitting position in Guillain-Barré patients.

- A portable system that can be used at home to reinforce the acute and sub-acute stages.

- A customizable system that offers multiple levels of difficulty that are based on the patients’ progression.[28]

There are two difficulty levels (low and medium) for the ABAR system, with six different games. This allows for various parameters to be adjusted based on patient specific need including level of difficulty, number of virtual sessions, rest period between virtual sessions, session time, target speed, and target display time. The low difficulty level consists of two virtual environments specific for sitting training, allowing for participants to perform medio-lateral and antero-posterior weight transferences in the sitting position. The medium difficulty level consists of four virtual environments that focus on standing training, based on static or dynamic balance rehabilitation.

The two patients with GBS participating in this novel research design completed three sessions per week for a total of 20 rehabilitation sessions, consisting of 30 minutes of traditional rehabilitation followed by 30 minutes of virtual motor rehabilitation using the ABAR system. The patient’s demonstrated improvements in static and dynamic clinical balance tests following the ABAR intervention, with more significant improvements demonstrated in static clinical balance tests.

In conjunction with the treatment plan outlined above, this virtual motor rehabilitation framework can assist with traditional rehabilitation interventions by enhancing gait and balance outcomes in an engaging manner that will maintain adherence. The difficulty levels and games depicted in the table above focus on simple functional movement tasks to target static and dynamic balance, which will translate to improved movement and gait patterns.

This technology is useful in the sense that it can be incorporated into any clinical practice or environment setting, including at home for patients. This system is portable with minimal equipment involved, which can allow for treatment use in areas including private clinics or hospitals. The portability of this treatment can provide allow patients in the acute phase that have been admitted to a hospital to receive effective treatment to limit some of the complications and progression of GBS. This will present a unique in-patient approach that can supplement traditional motor rehabilitation to enhance patient outcomes.

In contrast, accessibility to this form of technology may be difficult since it is not as commonly used as a treatment intervention. Although this technology is portable and can be easily integrated into various environments, there can be difficulty acquiring it depending on its availability. The use of this technology is relatively new to GBS treatment, meaning that there are many practitioners that are unfamiliar and do not have adequate training or expertise to implement this intervention effectively. Considering the uncommon prevalence of GBS, there is a lack of exposure and widespread use of this innovative technology that can make it difficult for healthcare providers to implement it into their clinical practice. To mitigate this challenge, additional research supporting the effectiveness of visual motor rehabilitation using the ABAR system should be conducted to showcase its efficacy. This can lead to greater awareness and education of its effectiveness in functional improvements for those living with GBS, and in turn result in greater accessibility for this technology.

Robotic Rehabilitation- Cybernic enhanced Ambulation:

- The use of technology such as overhead harness (used in patients with quadriplegia) to enhance balance in ambulation may benefit David once he is able to attain postural stability in sitting and standing.

- Interactive biofeedback (iBF) Cybernics treatment therapy using Hybrid Assistive Limb device (HAL) which picks up neural signals in the lower extremity and augments force during walking. This may benefit David significantly while he is initially learning to ambulate.

- An RCT conducted by Nakajima et al published in 2021, studied the use of Interactive biofeedback (iBF) Cybernics treatment therapy- Hybrid Assistive Device (HAL) in ambulation among patients with debilitating neuromuscular disorders. This study showed significant improvement in quality of gait and strength of the lower extremity compared to conventional use of just hoist after 9 sessions. Outcomes were attributed to patient’s motor learning and functional regeneration with HAL. It has shown to improve motor function in the legs in preliminary studies.[29]

- Another pre-post study conducted by Brinkemper et al published in 2021 evaluated the use of Hybrid Assistive Device (HAL) in improving the quality of gait in addition to functional parameters among patients with spinal cord injury and other neurogenerative diseases. There was a significant improvement in different phases of the gait cycle. After 12 weeks, sub-groups of patients showed increased step length and swing phase promoting the quality of gait [30] .

- Once David can walk without the use of a gait, we may progress him to jogging on a treadmill with the support of a overhead harness to prevent falls.

Outcome[edit | edit source]

Response to Complications and Adverse Events[12]

| Complication | Risk Factors/When to monitor | Plan |

|---|---|---|

| Pressure ulcers | Prolonged immobility, lack of sensation | Frequent inspection of high risk areas (e.g., malleoli, elbows, etc.). Education on pressure ulcers and the importance of frequent position changes. Therapeutic mobilization as frequently as possible. |

| Compression neuropathy | Prolonged immobility, lack of sensation | Education on the risk compression neuropathy and the importance of frequent position changes. Therapeutic mobilization as frequently as possible. |

| Contractures, tissue shortening | Prolonged muscle weakness and immobility | Education on pressure ulcers and the importance of frequent position changes. Therapeutic mobilization as frequently as possible. |

Referrals

A crucial portion of the health care system is to keep patients’ health care teams broad and interprofessional. The aspect of referring a patient to other health care professionals allows patients to get a well-rounded treatment and care plan, centered around their needs. It has been demonstrated through an overview of studies following GBS patients for 6 months, 1 year and 2 years following their diagnosis, that symptoms can widely range from severity of disability following discharge. [31]

Respiratory Therapist

For David, a respiratory therapist would be the first and prioritized referral. About 2 weeks following David’s admission into hospital, he started showing respiratory distress, which culminated in him being intubated. Respiratory failure begins to develop during the progressive stage in about a quarter of GBS patients, usually resulting in transfer to the ICU and being mechanically ventilated[1]. A respiratory therapist would be extremely beneficial for David as they can provide professional advice and treatment to help with current ventilation ability as well as any further prevention of ventilatory complications.

- Monitoring David’s use of accessory muscles, breathing depth, inspiratory and expiratory muscle fatigue/atrophy, coughing ability/strength.

- Drawing blood for monitoring his oxygen levels.

- Education on proper breathing strategies for both the David and his support system

- Proper breathing techniques after extubating.

- Making sure David knows to move arms (within his ability) throughout the day to avoid contractures.

- Providing reassurance to David that around 80% of patients who are mechanically ventilated make extensive recoveries within their first year after onset.[12]

Occupational Therapist

A second referral for David would be to an Occupational Therapist. David is currently unable to ambulate due to bilateral lower extremity impairment as well as sensory and motor loss to upper extremity as well. An occupational therapist’s role is to assist a patient in the activities of daily living (ADLs), help their home environment become more accessible, fitting and prescribing certain aids that may help people with daily activities (gait aids, reaching objects, sticky mats, etc.).

- OT would assist David with functional exercises that will help him independently carry out ADLs and IADLs.

- With the addition of resistance training if able[32]

- Assist David with fine motor control of the hand, work will be affected as he uses a mouse throughout the day.

- Help David with sensation in upper extremities, in turn will also contribute to fine motor skills as well.

- Provide education on possible reorganization of household items or rooms to accommodate gait aid as well as making ADLs easier to carry out.

Social Worker or Psychologist

The third referral being made for David would be to a social worker or a psychologist. David has only been diagnosed with GBS for less than a month, this represents a severe change to his life, lifestyle, and hobbies. David was previously active and loved to spend time with his wife and two daughters, and held a successful job in the software development industry. A psychologist would be very beneficial for David to help him with reassurance, grounding, and provision of mental support around these lifestyle changes.

- Help connect David with support groups with other patients with GBS and their journeys and experiences.

- Giving David someone to talk to about this traumatic change in his life.

- Help David cope with any stress or anxiety initiated by not being able to care for his wife and daughters like he used to.

- Also, guidance for both David and his wife following this diagnosis, it has been shown that some anxiousness and social dysfunction can occur within family members/relatives[31]

Questions[edit | edit source]

1. Select two correct answers below regarding Guillain-Barré Syndrome:

- Unilateral numbness, tingling, and/or pain begins in the hands and feet

- GBS is a rare autoimmune disorder that affects the Schwann cells

- GBS is more common in women than men

- The incidence of subtypes is similar between countries

- The most common form of GBS is Acute Inflammatory Demyelinating Polyradiculoneuropathy (AIDP)

2. Select the correct answer:

- GBS patients should always exercise to muscular failure to reap the greatest benefits

- GBS patients should have decreased rest breaks through their home exercise program

- PNF stretching has been shown to be effective for improving motor function and control in patients with GBS

- GBS patients should avoid isometric exercises due to over-reliance on muscular contractions and not compensatory movements

3. Select the correct answer:

- Hemiparesis is a common presentation of GBS

- GBS only affects skeletal muscle

- GBS patients suffer from Uhthoff’s Phenomenon

- GBS can be triggered by bacterial or viral infection

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Willison HJ, Jacobs BC, van Doorn PA. Guillain-barre syndrome. The Lancet. 2016 Aug 13;388(10045):717-27.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Hughes RA, Cornblath DR. Guillain-barre syndrome. The Lancet. 2005 Nov 5;366(9497):1653-66.

- ↑ Abara WE, Gee J, Marquez P, Woo J, Myers TR, DeSantis A, Baumblatt JA, Woo EJ, Thompson D, Nair N, Su JR. Reports of Guillain-Barré Syndrome After COVID-19 Vaccination in the United States. JAMA Network Open. 2023 Feb 1;6(2):e2253845-.

- ↑ Ropper AH. The Guillain–Barré syndrome. New England journal of medicine. 1992 Apr 23;326(17):1130-6.

- ↑ Van den Berg B, Walgaard C, Drenthen J, Fokke C, Jacobs BC, Van Doorn PA. Guillain–Barré syndrome: pathogenesis, diagnosis, treatment and prognosis. Nature Reviews Neurology. 2014 Aug;10(8):469-82.

- ↑ Alshekhlee A, Hussain Z, Sultan B, Katirji B. Guillain–Barré syndrome: incidence and mortality rates in US hospitals. Neurology. 2008 Apr 29;70(18):1608-13.

- ↑ Shahrizaila N, Lehmann HC, Kuwabara S. Guillain-Barré syndrome. The lancet. 2021 Mar 27;397(10280):1214-28.

- ↑ Walling A, Dickson G. Guillain-Barré syndrome. American family physician. 2013 Feb 1;87(3):191-7.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Wijdicks EF, Klein CJ. Guillain-barre syndrome. InMayo clinic proceedings 2017 Mar 1 (Vol. 92, No. 3, pp. 467-479). Elsevier.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Govoni V, Granieri E. Epidemiology of the Guillain-Barré syndrome. Current opinion in neurology. 2001 Oct 1;14(5):605-13.

- ↑ 1. GBS (Guillain-Barré Syndrome) and vaccines [Internet]. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2023 [cited 2023 May 10]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccinesafety/concerns/guillain-barre-syndrome.html

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Leonhard SE, Mandarakas MR, Gondim FA, Bateman K, Ferreira ML, Cornblath DR, van Doorn PA, Dourado ME, Hughes RA, Islam B, Kusunoki S. Diagnosis and management of Guillain–Barré syndrome in ten steps. Nature Reviews Neurology. 2019 Nov;15(11):671-83.

- ↑ Hughes RA, Newsom-Davis JM, Perkin GD, Pierce JM. Controlled trial of prednisolone in acute polyneuropathy. The Lancet. 1978 Oct 7;312(8093):750-3.

- ↑ van Koningsveld R, Steyerberg EW, Hughes RA, Swan AV, van Doorn PA, Jacobs BC. A clinical prognostic scoring system for Guillain-Barré syndrome. The Lancet Neurology. 2007 Jul 1;6(7):589-94.

- ↑ Hahn AF. The challenge of respiratory dysfunction in Guillain-Barré syndrome. Archives of Neurology. 2001 Jun 1;58(6):871-2.

- ↑ Zheng P, Tian DC, Xiu Y, Wang Y, Shi FD. Incidence of Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) in China: A national population-based study. The Lancet regional health Western Pacific. 2022;18:[[1]].

- ↑ Kidd D, Stewart G, Baldry J, Johnson J, Rossiter D, Petruckevitch A, et al. The Functional Independence Measure: A comparative validity and reliability study. Disability and rehabilitation. 1995;17(1):10–4.

- ↑ Moore JL, Potter K, Blankshain K, Kaplan SL, OʼDwyer LC, Sullivan JE. A Core Set of Outcome Measures for Adults With Neurologic Conditions Undergoing Rehabilitation: A CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE. Journal of neurologic physical therapy. 2018;42(3):174–220.

- ↑ Naqvi U, Sherman Al. Muscle Strength Grading. StatPearls [Internet]. 2022 Aug. [cited 2023 May 11]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK436008/

- ↑ Cuthbert SC, Goodheart J. On the reliability and validity of manual muscle testing: a literature review. Chiropractic & osteopathy. 2007;15(4):4–4.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 21.4 21.5 21.6 21.7 21.8 21.9 Guidelines for Physical and Occupational Therapy. GBS CIDP Foundation International

- ↑ Meena AK, Khadilkar SV, Murthy JM. Treatment guidelines for Guillain–Barré syndrome. Annals of Indian Academy of Neurology. 2011 Jul;14(Suppl1):S73.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Simatos Arsenault N, Vincent PO, Yu BH, Bastien R, Sweeney A. Influence of exercise on patients with Guillain-Barré syndrome: a systematic review. Physiotherapy Canada. 2016;68(4):367-76.

- ↑ Khan F, Pallant JF, Amatya B, Ng L, Gorelik A, Brand BC, Brand C. Outcomes of high-and low-intensity rehabilitation programme for persons in chronic phase after Guillain-Barré syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine. 2011 Jun 5;43(7):638-46.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 Nehal S, Manisha S. Role of physiotherapy in Guillain Barre Syndrome: A narrative review. Int J Heal. Sci. & Research: 5 (9): 529. 2015;540.

- ↑ Dayyer K, Rahnama N, Nassiri J. Effect of Eight-Week Selected Exercises on Strength, Range of Motion (RoM) and Quality of Life (QoL) in Patients with GBS. Neonat Pediatr Med. 2018;4(173):2.

- ↑ Karper WB. Effects of low-intensity aerobic exercise on one subject with chronic-relapsing Guillain-Barré syndrome. Rehabilitation Nursing Journal. 1991 Mar 1;16(2):96-8.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 Albiol-Perez S, Forcano-García M, Muñoz-Tomás MT, Manzano-Fernández P, Solsona-Hernández S, Mashat MA, Gil-Gómez JA. A novel virtual motor rehabilitation system for Guillain-barre syndrome. Methods of Information in Medicine. 2015;54(02):127-34.

- ↑ Nakajima T, Sankai Y, Takata S, Kobayashi Y, Ando Y, Nakagawa M, Saito T, Saito K, Ishida C, Tamaoka A, Saotome T. Cybernic treatment with wearable cyborg Hybrid Assistive Limb (HAL) improves ambulatory function in patients with slowly progressive rare neuromuscular diseases: a multicentre, randomised, controlled crossover trial for efficacy and safety (NCY-3001). Orphanet journal of rare diseases. 2021 Dec;16(1):1-8.

- ↑ Brinkemper A, Aach M, Grasmücke D, Jettkant B, Rosteius T, Dudda M, Yilmaz E, Schildhauer TA. Improved physiological gait in acute and chronic SCI patients after training with wearable cyborg hybrid assistive limb. Frontiers in Neurorobotics. 2021 Aug 26;15:723206.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 (1) Anette Forsberg. Guillain-Barré Syndrome : Disability, Quality of Life, Illness Experiences and Use of Healthcare. Sweden: Karolinska Institutet (Sweden); 2006.

- ↑ Ko KJ, Ha GC, Kang SJ. Effects of daily living occupational therapy and resistance exercise on the activities of daily living and muscular fitness in Guillain-Barré syndrome: a case study. Journal of Physical Therapy Science. 2017;29(5):950–3.