Chronic Neck Pain

Original Editor - Axel Antoine

Top Contributors - Axel Antoine, Laura Ritchie, Kim Jackson, Rachael Lowe, Simisola Ajeyalemi, Lauren Lopez, Jess Bell, Olajumoke Ogunleye, Admin, Evan Thomas, George Prudden, Joris Servranckx, Eva Roose1, WikiSysop and Claire Knott

Introduction[edit | edit source]

The International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) in its classification of Chronic Pain defines cervical spinal pain as "pain perceived anywhere in the posterior region of the cervical spine, from the superior nuchal line to the first thoracic spinous process". The Bone and Joint Decade 2000-2010 Task Force on Neck Pain and Its Associated Disorders describes Neck pain as "pain located in the anatomical region of the neck with or without radiation to the head, trunk, and upper limbs".

Pain is classified as chronic when it has a duration of 12 weeks or more. Chronic neck pain often presents as widespread hyperalgesia on palpation and in both passive and active movements in neck and shoulder area[1].

Considerable research has shown that psychosocial factors are an important prognostic indicator of prolonged disability in individuals with neck pain[2]. It is well known that chronic pain is often associated with anatomical, psychological, social, and professional factors. This is consistent with the biopsychosocial model, which considers pain to be a dynamic interaction between biological, psychological, and social factors unique to each individual.

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

Although the natural history of neck pain appears to be favourable, rates of recurrence and chronicity are high[3]. Blanpied et al reviewed the literature and found that:

- 30% of patients with neck pain will develop chronic symptoms, with neck pain of greater than 6 months in duration affecting 14% of all individuals who experience an episode of neck pain.

- 37% of individuals who experience neck pain will report persistent problems for at least 12 months. Five percent of the adult population with neck pain will be disabled by the pain, representing a serious health concern.

- Five percent of the adult population with neck pain will be disabled by the pain, representing a serious health concern.

The economic burden due to disorders of the neck is high, and includes costs of treatment, lost wages, and compensation expenditures

Individuals with chronic neck pain are largely middle aged and the majority are female[3]. Clinicians should consider age greater than 40, coexisting low back pain, a long history of neck pain, cycling as a regular activity, loss of strength in the hands, worrisome attitude, poor quality of life, and less vitality as predisposing factors for the development of chronic neck pain[3].

Clinical Course[edit | edit source]

The overall balance of evidence supports a variable view of the clinical course of neck pain. Recovery appears to occur most rapidly in the first 6 to 12 weeks post injury, with considerable slowing after that and little recovery after 12 months[3][4]. Once considered chronic, the course may be stable or fluctuating, but in most cases can be best classified as recurrent, characterised by periods of relative improvement followed by periods of relative worsening.

Pain intensity, level of self-rated disability, pain-related catastrophising, post traumatic stress symptoms (traumatic onset only), and cold hyperalgesia may indicate a potential for chronicity[3].

Assessment[edit | edit source]

Assessment of chronic neck pain should follow the usual examination for the cervical spine. However it is important to be aware of the differing impairments that individuals with chronic pain may present:

- Chronic conditions often have a lower degree of irritability[3].

- Individuals with chronic neck pain often display impaired proprioception. A high-quality review by Stanton et al[5] concluded that these individuals are worse than asymptomatic controls at head-to-neutral repositioning tests.

- Deficits in cervicoscapulothoracic strength and motor control may be present in individuals with subacute or chronic neck pain[3]

It is well know that Psychosocial factors may contribute to an individuals persistent pain and disability, and the transition of an acute condition to a chronic, disabling condition. Certain outcome measures can be used to evaluate psychosocial factors:

- Fear Avoidance Questionnaire

- Beck Depression Inventory

- Depression Anxiety Screening Scale

- Pain Catastrophizing Scale

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

There is a lack of evidence for medical management of chronic neck pain. Trials testing the use of botulinum injections, steroid injections and muscle relaxants have not proven to be efficacious.

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

Treatment Based Classification Approach[edit | edit source]

The treatment based classification approach to neck pain revision in 2017[3] (CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE) separately listed interventions for chronic neck pain: (level of evidence 1a)

Neck pain with mobility deficits

Clinicians should provide a multimodal approach of the following:

- Thoracic manipulation and cervical manipulation or mobilization

- Mixed exercise for cervical/scapulothoracic regions: neuromuscular exercise (eg, coordination, proprioception, and postural training), stretching, strengthening, endurance training, aerobic conditioning, and cognitive affective elements

- Dry needling, laser, or intermittent mechanical/manual traction

- Clinicians may provide neck, shoulder girdle, and trunk endurance exercise approaches and patient education and counseling strategies that promote an active lifestyle and address cognitive and affective factors.

Chronic neck pain with movement coordination impairments (including WAD)

Clinicians may provide the following:

- Patient education and advice focusing on assurance, encouragement, prognosis, and pain management

- Mobilisation combined with an individualised, progressive sub maximal exercise program including cervicothoracic strengthening, endurance, flexibility, and coordination, using principles of cognitive behavioural therapy

- TENS

Chronic neck pain with headache

Clinicians should provide cervical or cervicothoracic manipulation or mobilisations combined with shoulder girdle and neck stretching, strengthening, and endurance exercise.

Chronic neck pain with radiating pain

- Clinicians should provide mechanical intermittent cervical traction, combined with other interventions such as stretching and strengthening exercise plus cervical and thoracic mobilisation/ manipulation.

- Clinicians should provide education and counselling to encourage participation in occupational and exercise activities

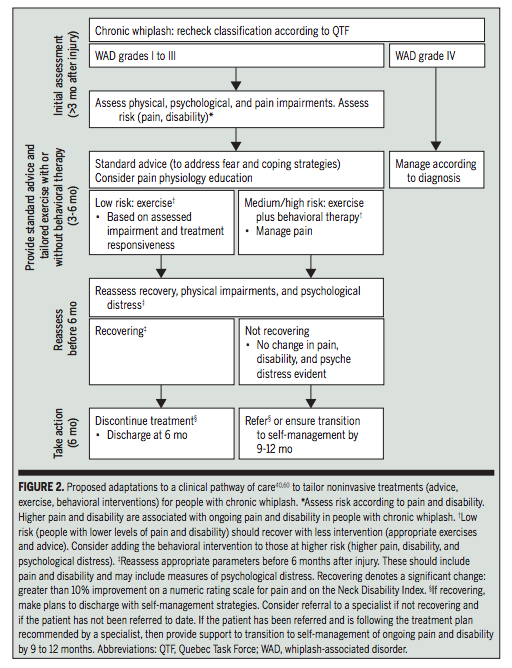

Chronic Whiplash Clinical Care Pathway[edit | edit source]

[6] (LOE 5) ==

Behavioural Interventions[edit | edit source]

Education is a key component of managing individuals with chronic neck pain and behavioural interventions should play a role in the management of people with chronic whiplash[6] (LOE 5). Guidelines recommend that individuals be provided with information about how to cope with pain and disability, particularly as their symptoms transition to the chronic phase. Key concepts to address include reducing catastrophic thought, addressing unhelpful beliefs, addressing fear of movement and providing active coping strategies to assist patients to cope with pain[6] (LOE 5). There is some preliminary evidence that pain neurophysiology education in chromic WAD improves both pain behavior and pain thresholds[6] (LOE 5).

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) is a method that can help manage problems by changing the way patients would think and behave. It is not designed to remove any problems but help manage them in a positive manner. The CBT approach to LBP can be as effectively applied to neck pain and can be included in your education strategy.

If relevant psychosocial factors are identified, the rehabilitation approach may need to be modified. An emphasis on active rehabilitation and positive reinforcement of functional accomplishments is recommended. Graded exercise programs that direct attention towards attaining certain functional goals and away from the symptom of pain have also been recommended. Finally, graduated exposure to specific activities that a patient fears as potentially painful or difficult to perform may be helpful.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Misailidou V, Malliou P, Beneka A, Karagiannidis A, Godolias G, Assessment of patients with neck pain: a review of definitions, selection criteria, and measurement tools; Journal of Chiropractic Medicine Jun 2010; 9(2): 49–59. (5)

- ↑ Childs MJ, Fritz JM, Piva SR, Whitman JM. Proposal of a classification system for patients with neck pain. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy. 2004 Nov;34(11):686-700.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 Blanpied PR, Gross AR, Elliott JM, Devaney LL, Clewley D, Walton DM, Sparks C, Robertson EK, Altman RD, Beattie P, Boeglin E. Neck Pain: Revision 2017: Clinical Practice Guidelines Linked to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health From the Orthopaedic Section of the American Physical Therapy Association. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy. 2017 Jul;47(7):A1-83

- ↑ Sterling M, Hendrikz J, Kenardy J. Compensation claim lodgement and health outcome developmental trajectories following whiplash injury: a prospective study. Pain. 2010;150:22-28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. pain.2010.02.013

- ↑ Stanton TR, Leake HB, Chalmers KJ, Moseley GL. Evidence of impaired proprioception in chronic, idiopathic neck pain: systematic review. Phys Ther. 2016;96:876-887

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Rebbeck T. The Role of Exercise and Patient Education in the Noninvasive Management of Whiplash: A Clinical Commentary. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy. 2017 Jun 16(0):1-32.