Cervical Instability

Original Editor - Mary-Kate McCoy, Heather Lampe as part of the Temple University Evidence-Based Practice Project

Top Contributors - Vanbeylen Antoine, Mary-Kate McCoy, Rachael Lowe, Admin, Pieter Piron, Sara Evenepoel, David Herteleer, Kim Jackson, Lucinda hampton, Heather Lampe, Laura Ritchie, Nick Van Doorsselaer, Daniele Barilla, Tony Lowe, Scott A Burns, WikiSysop, Simisola Ajeyalemi, Jess Bell, Olajumoke Ogunleye, Beth Potter, Evan Thomas and 127.0.0.1

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

Clinical instability of the cervical spine (CICS) is defined as the inability of the spine under physiological loads to maintain its normal pattern of displacement so that there is no neurological damage or irritation, no development of deformity, and no incapacitating pain.[1] While no tools exists for the assessment of upper cervical ligamentous instability, an approach that takes into account risk factors, patient history, and examination results to make judicious decisions about patient management has been recommended[2].

This 7 minute video is provides a good summary of CICS

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

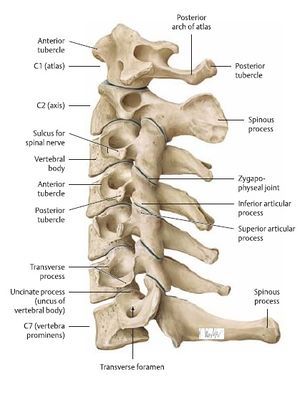

The cervical spine consist of 7 separate vertebrae. See Cervical Anatomy also.

- The first two vertebrae (referred as upper cervical spine) are highly specialised and differ from the other 5 cervical vertebrae (lower cervical) regarding anatomical structure and function.

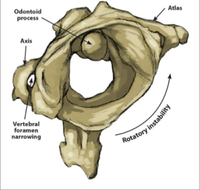

- The upper cervical spine is made of the atlas (C1) and the axis (C2) the joint atlanto-occipital joint and the atlanto-axial joint

- Atlantoaxial joint is responsible for 60% of all cervical rotation

- Atlanto-occipital joint is responsible for 33% of flexion and extension. [4]

The cervical spine has sacrificed stability for mobility and is therefore vulnerable to injury. The craniocervical junction (atlanto-occipital joint), the lower atlanto-axial joint and other cervical segments are reinforced by internal as well as external ligaments. They secure the spinal stability of the cervical spine as a whole, together with surrounding postural muscles and allow cervical motion. They also provide proprioceptive information throughout the spinal nerve system to the brain.

The spinal stabilising system is divided into 3 functionally integrated subsystems [5][1][6]

- Passive subsystem – spinal column (vertebrae, facet joints, intervertebral disc, spinal ligaments and joint capsules)

- Active subsystem – spinal muscles (muscles and tendons)

- Control subsystem – neural feedback (neural control centers and force transducers located in ligaments, tendons, muscles)

Aetiology[edit | edit source]

Causes include:

- Trauma (one major trauma or repetitive microtrauma or delayed or missed diagnosis of cervical spine injury after trauma (car accident rugby neck injury) . The traumatic flexion-extension moment exerted on the spine can cause ligamentous disruption with subsequent atlantoaxial instability (AAI) / upper cervical instability[7].

- Inflammatory arthritides eg.Ankylosing Spondylitis (Axial Spondyloarthritis), Rheumatoid arthritis, due to the progressive destruction of the cervical skeletal structures. The most affected region is the upper cervical spine and C4-C5. [8]

- Congenital collagenous compromise (e.g. syndromes: Down’s, Ehlers-Danlos, Grisel, Morquio) The atlanto-axial instability (AAI) is considered as a developmental anomaly often occurring in patient with the Down’s Syndrome (DS). It affects 6.8 to 27% of the population with DS.[9] Usually, persons with congenital anomalies do not become symptomatic before midlife adulthood. The spine is assumed to be able to accommodate differing regions of hypermobility and fusions. With time, the degenerative changes occurring in the lower cervical spine increase rigidity and alter the balance. This gradual loss of motion places increasing loads on the atlantoaxial articulation.

- Recent neck/head/dental surgery.

Clinical Presentation/Examination[edit | edit source]

Symptoms listed in descending rank

- Intolerance to prolonged static postures

- Fatigue and inability to hold head up

- Better with external support, including hands or collar

- Frequent need for self-manipulation

- Feeling of instability, shaking, or lack of control

- Frequent episodes of acute attacks

- Sharp pain, possibly with sudden movements

- Head feels heavy

- Neck gets stuck, or locks, with movement

- Better in unloaded position such as lying down

- Catching, clicking, clunking, and popping sensation

- Past history of neck dysfunction or trauma

- Trivial movements provoke symptoms

- Muscles feel tight or stiff

- Unwillingness, apprehension, or fear of movement

- Temporary improvement with clinical manipulation

The 12 physical examination findings included:

- Poor coordination/neuromuscular control, including poor recruitment and dissociation of cervical segments with movemen

- Abnormal joint play

- Motion that is not smooth throughout range (of motion), including segmental hinging, pivoting, or fulcruming

- Aberrant movement

- Hypomobility of upper thoracic spine

- Increased muscle guarding, tone, or spasms with test movements

- Palpable instability during test movements

- Jerkiness or juddering of motion during cervical movement

- Decreased cervical muscle strength

- Catching, clicking, clunking, popping sensation heard during movement assessment

- Fear, apprehension, or decreased willingness to move during examination

- Pain provocation with joint-play testing

Symptoms can be different but the most frequent clinical findings are[1]:

- Tenderness in the cervical region

- Referred pain in the shoulder or paraspinal region

- Cervical radiculopathy

- Cervical myelopathy

- Headaches

- Paraspinal muscle spasm

- Decreased cervical lordosis

- Neck pain with sustained postures

- Hypermobility and soft end-feeling in passive motion testing

- Poor cervical muscle strength (multifidus, longus capitis, longus colli)

Because a definitive diagnostic tool has not been developed, cervical clinical instability will continue to be diagnosed through clinical findings, including history, subjective complaints, visual analysis of active motion quality, and manual examination methods[1].

The following tests can be used to measure cervical instability[10] but little is known about the diagnostic accuracy of upper cervical spine instability tests:

- Sharp-Purser test

- Transverse Ligament Stress Test

- Cervical flexion-rotation test

- Neck Flexor Muscle Endurance Test and Craniocervical flexion test

One high quality systematic review by Hutting et al[11] revealed poor diagnostic accuracy for all upper cervical ligament instability tests evaluated. In general, these tests have sufficient specificity and can rule in upper cervical ligamentous instability, but degrees of sensitivity varied.

Magee et al reported poor cervical muscle endurance is one of the clinical findings we find with cervical instability. A good way to test these muscles (the deep cervical flexor muscles, the longus capitis and longus colli) is the craniocervical flexion test (CCFT) which is a test of neuromotor control. The main goal of the test is to apply an isometric force on a pressure sensor placed behind the neck without using the superficial cervical flexors. The construct validity of the craniocervical flexion test has ben verified in a laboratory setting[12]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Certain Patients that might present with acute neurologic symptoms that raise alarm for cervical compression or neck pain but without a specific origin should undergo a thorough physical examination and radiographic evaluation to determine the source.

More often than not are the findings nonspecific and can be representative of any number of related conditions. Neck pain, weakness and other characteristics also present in cervical spine instability can also be seen in the following cervical diseases including the following: [13][14]

- Cervical strain

- Cervical trauma or fracture

- Occipital headaches

- Degenerative disease of the spine

- Previously undiagnosed syndrome

- Neurological involvement

- Progressive neck pain

- Resistant neck pain

- Central or lateral disc herniation

- Guillain-Barré syndrome

- Cervical spondylosis

- Pathologic fracture

- Cervical canal stenosis

- Facet joint pathologies

- Infections: discitis, osteomyelitis, etc.

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

Evaluation for spinal instability differs in the acute traumatic setting versus the chronic degenerative setting.

Acute setting: Canadian C-spine rule used to determine what patients need cervical spine imaging

Chronic setting: History and physical exam help guide the initial imaging modality, which will often be plain x-rays. However, more advanced detail imaging such as dynamic imaging, MRI, CT and studies with contrast, is often necessary to detect instability.[15]

Cervical instability is a diagnosis based primarily on a patient’s history and reported symptoms.

Imaging

Radiologic Diagnosis of Instability:

- Cervical radiographs

- Segmental kyphosis greater than 11 degrees

- Anterolisthesis greater than 3.5 mm of one vertebral body on another

- Lateral neutral, flexion and extension xrays

- Forward displacement of one vertebrae on another: spondylolisthesis

- Backward displacement of one vertebrae on another: retrolisthesis

- Narrowing of the intervertebral foramen and loss of disc thickness

- An abrupt apparent change in pedicle length

- Anteroposterior xrays with lateral bending

- Bending to one side or another

- Decreased bending to one side with loss of both vertebral rotation and tilt with actual opening of the disc on the side to which the patient is bending

- An abnormal degree of disc closure on the side to which the patient is bending

- Malalignment of spinous processes and pedicles

- Lateral translation of one vertebra on another due to an abnormal degree of rotation

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

These three questionnaires are specific and valid instruments to evaluate the neckpain and dysfunction. [16][17]

- Neck disability index

- Neck bournemouth questionnaire

- Neck pain and disability scale.

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

The current definitions of spine instability are not uniformly accepted nor applied. Therefore, there is no consensus about the timing of conservative versus surgical treatment of CICS. The understandings of spinal biomechanics need improvement to determine and differentiate the relationship and severity between radiographic instability and its clinical manifestation. This gap in knowledge makes it difficult for all disciplines involved in the diagnosis and treatment of patients suffering from disorders of spine stability.[15]

In the past few decades nonoperative manoeuvres like traction, cast immobilizations and long periods of bed rest had been replaced by the use of instrumentation to stabilise the spine after a trauma (reducing the risk of negative sequelae of long term bed rest)[18].

The cervical stability can be achieved by using posterior fixation such as lateral mass plating, processus spinosus or facet wiring and cervical pedicle screws. The choice of which fixation is best, can be made by the surgeon after seeing a CT-scan or MRI.

In a retrospective study of Fehlings, the cervical spine stabilisation was successful in 93% off the cases[19].

The fixation procedure also holds some risks. It is possible that the spinal cord, vertebral artery, spinal nerve and facet joints get injured.

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

Conservative treatment is indicated when cervical clinical instability does not severely involve or threaten neurological structures. The goal of nonsurgical treatment should be to enhance the function of the spinal stabilising subsystems and to decrease the stresses on the involved spinal segments.

Posture Education and Spinal Manipulation

- Decreases stresses on the passive subsystem[1]

- Proper posture: reduces the loads placed on the spinal segments at end-ranges and returns the spine to a biomechanically efficient position[1][5]

- Spinal manipulation can be performed on hypomobile segments above and below the level of instability, what eventually will result in a distribution of the spinal movement across several segments. Also the mechanical stresses on the level of clinical instability are believed to be decreased[1]

- Video over joint mobilisation: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Rn1Ed2SxTx0

Strengthening Exercises

- Enhances the function of the active subsystem.

- The cervical multifidus may provide stability via segmental attachments to cervical vertebrae.

- The longus colli and capitus provide anterior stability.

- Strengthening the stabilizing muscles may enable those muscles to improve the quality and control of movement occurring within the neutral zone.[7][13]

- Exercise video: Neck strength and stability www.youtube.com/watch

Proprioception Exercises

One of the main goals of the non-surgical treatment is to improve the quality of controlled motion. Therefore proprioception exercises must be used, this will improve the control of movement in the neutral zone.

Post-Operative Rehabilitation

In a more specific situation such as post-operative rehabilitation the treatment can differ:

- The patient is not required to wear a brace.

- After 6 weeks it is not encouraged to do any lifting more than 4kg as also overhead work.

- The rehabilitation begins at week 6, mostly a basic stability exercises program.

- No cervical strengthening or ranges of motion exercises are encouraged in the first 6 months.

- The exercises or mainly focused on the neutral postural alignment, were the patients are recommended to us there trunk, hips and chest to produce proper cervical alignment.

Example of Management Programme[edit | edit source]

Anita R. Gross et al listed an evidence-based home neck care exercise program that can be included if the CCFT test was found positive. It is in 3 progressive phases. These exercises should be judiciously tailored to individual circumstances and applied as indicated based on a clinical examination[20]

Phase 1

- Craniocervical flexion- Start with pressure biofeedback inflated to 20 mmHg. Make sure your chin and forehead are lined up. Nod your head, keeping the large neck muscles soft and bringing the reading up to 22 mmHg. Work up to ten 10-second holds. Then progress to 24, 26, and 28 mmHg.

- Neck active range of motion - Start with your head in neutral, then:

- Tilt backward

- Bend forward

- Tilt side to side

- Turn side to side

- Resisted shoulder extension with elbow flexed - “Set” your cervical spine, abdominals and scapulae, then extend your arm with elbows bent backward.

- Resisted shoulder extension with elbow straight - “Set” your cervical spine, abdominals, and scapulae, then extend your arm backward.

- Resisted shoulder shrug -“Set” your cervical spine, abdominals, and scapulae, then slightly abduct arms and minimally shrug shoulders.

- Resisted elbow exercise - “Set” your cervical spine, abdominals, and scapulae, then:

- Bend

- Straighten level 1

- Straighten level 2 your elbows.

Phase 2

- Headlift - Start with your head in neutral (chin and forehead lined up), do a chin nod and lift your head, while maintaining your chin tucked. Hold for a count of 5 to 10 seconds and return smoothly with your chin still tucked.

- Isometric neck strength - Place your hand on your head and resist. Hold for a count of 5 to 10 seconds:

- Bending

- Tilting backward

- Tilting sideways

- Turning your head

- Shoulder stretches - “Set” your cervical spine, abdominals, and scapulae hold for 20 seconds.

- Clasp your hands behind your back and squeeze your scapulae together

- Hold your arms out in front of you and reach forward feeling a stretch between your scapulae

- Reach your arms overhead

- Shoulder stretches - “Set” your cervical spine, abdominals, and scapulae, hold for 20 seconds.

- With elbows at shoulder level, lean into a corner to feel a stretch in the front of your chest

- With elbows at eye level lean into a corner to feel a stretch

- Transverse abdominus - Tense your lower abdomen by imagining drawing your hip bones together (or apart if that works better), hold for 10 seconds. Then let the 1 leg fall out over a 10-second count

- Wall sit - “Set” cervical spine, transverse abdominus, and scapulae, then slide down the wall into a semi-squat position. Hold for as long as you can, working up to 2 minutes.

Phase 3

- Shoulder strength - “Set” cervical spine, abdominals, and scapulae then “hug a tree.”

- Shoulder strengthen - “Set” cervical spine, abdominals, and scapulae, then elevate arms into a “reverse fly.”

- Resisted neck: craniocervical flexion and oblique flexion - “Set” cervical spine, abdominals, and scapulae, then

- Nod head

- Nod head at a slight oblique angle

- Resisted neck extension - “Set” cervical spine, abdominals, and scapulae:

- First nod your head

- Then tilt your head backward

- The focus of extension is in the lower neck

- Resisted neck side flexion - “Set” cervical spine, abdominals, and scapulae, then tilt head to the side.

- Resisted neck rotation - “Set” cervical spine, transverse abdominus, and scapulae, then rotate head.

In the table below you can find the dosage recommendations for the evidence-based home neck care exercise program.

| Exercise | Equipment used | Load (pain-free or low pain) | Rep | Set | Frequency | Duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Specific neck

Craniocervical flexors 4 isometric 4 isotonic |

Pressure biofeedback Head weight/self resist Rubber tubing |

3 levels mmHg Pain-free range Yellow/red |

10 20 20 |

1 3 3 |

3/wk |

5 min 15 min 20 min |

| Postural/upper extremity

Isotonic |

Rubber tubing |

Green/ blue |

20 | 3 |

3/wk |

12 min |

|

Trunk Isotonic |

Body weight |

20 | 3 |

3/wk |

12 min | |

|

Stretch Specific neck 5 Scapulothoracic 2 |

N/A N/A |

3 3 |

1 1 |

Daily Daily |

10 min 5 min |

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 K.A. Olson, D. Joder, Diagnosis and treatment of Cervical Spine Clinical Instability, Journal of Orthopaedic Sports Physical Therapy, April 2001. (LoE:4)

- ↑ Blanpied PR, Gross AR, Elliott JM, Devaney LL, Clewley D, Walton DM, Sparks C, Robertson EK, Altman RD, Beattie P, Boeglin E. Neck Pain: Revision 2017: Clinical Practice Guidelines Linked to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health From the Orthopaedic Section of the American Physical Therapy Association. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy. 2017 Jul;47(7):A1-83.

- ↑ Dpt Orthopeadics Cervical Instability Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k6hUT1kBoEc&feature=youtu.be (last accessed 4.2.2020)

- ↑ Windsor, R. “Cervical Spine Anatomy.” Updated april 9, 2013 (http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1948797-overview#a30)

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Panjabi, M. M. “The Stabilizing System of the Spine. Part II. Neutral Zone and Instability Hypothesis.” Journal of Spinal Disorders 5, no. 4: 390–397, December 1992 (LoE:5)

- ↑ M. Takeshi et Al., Soft-Tissue Damage and Segmental Instability in Adult Patients with Cervical Spinal Cord Injury Without Major Bone Injury, Spine Journal, December 2012.fckLR

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Yeo, Chang Gi, Ikchan Jeon, and Sang Woo Kim. “Delayed or Missed Diagnosis of Cervical Instability after Traumatic Injury: Usefulness of Dynamic Flexion and Extension Radiographs.” Korean Journal of Spine 12, no. 3 (September 2015): 146–49 (LoE:3B)

- ↑ Macovei, Luana-Andreea, and Elena Rezuş. “CERVICAL SPINE LESIONS IN RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS PATIENTS.” Revista Medico-Chirurgicală̆ a Societă̆ţ̜ii De Medici Ş̧i Naturaliş̧ti Din Iaş̧i 120, no. 1 (March 2016): 70–76.

- ↑ Myśliwiec, Andrzej, Adam Posłuszny, Edward Saulicz, Iwona Doroniewicz, Paweł Linek, Tomasz Wolny, Andrzej Knapik, Jerzy Rottermund, Piotr Żmijewski, and Paweł Cieszczyk. “Atlanto-Axial Instability in People with Down’s Syndrome and Its Impact on the Ability to Perform Sports Activities - A Review.” Journal of Human Kinetics 48 (November 22, 2015): 17–24.

- ↑ Hutting N, Scholten-Peeters GG, Vijverman V, Keesenberg MD, Verhagen AP. Diagnostic accuracy of upper cervical spine instability tests: a systematic review.Phys Ther. 2013 Dec;93(12):1686-95. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20130186. Epub 2013 Jul 25.

- ↑ Hutting N, Scholten-Peeters GG, Vijverman V, Keesenberg MD, Verhagen AP. Diagnostic accuracy of upper cervical spine instability tests: a systematic review. Phys Ther. 2013;93:1686-1695. https://doi.org/10.2522/ ptj.20130186

- ↑ Jull GA; Clinical assessment of the deep cervical flexor muscles: the craniocervical flexion test; J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2008 Sep;31(7):525-33.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Cook C, Brismee JM, Fleming R, et al (2005). Identifiers suggestive of clinical cervical spine instability: a Delphi study of physical therapists. Physical Therapy 85(9):895-906. (LoE:5)

- ↑ Magee DJ, Zachazewski JE,Quillen Ws : Cervical spine in Pathology an intervention in Musculoskeletal Rehabilitation p17-63 ,2009, St-Louis, Saunders Elsevier

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Vincent Huang, MD, Andrew Lederman, MD Nov 2016 SPINAL INSTABILITY: DEFINITION, THEORY AND ASSESSMENT OF SPINAL COLUMN FUNCTION AND DYSFUNCTION Available from: ☀https://now.aapmr.org/spinal-instability-definition-theory-and-assessment-of-spinal-column-function-and-dysfunction/ (last accessed 4.2.2020)

- ↑ Ralph E. Gay; Comparison of the Neck Disability Index and the Neck Bournemouth Questionnaire in a sample of patients with chronic uncomplicated neck pain; Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics. Volume 30, Issue 4, May 2007, Pages 259–262

- ↑ Steven J Linton, A cognitive-behavioral group intervention as prevention for persistent neck and back pain in a non-patient population: a randomized controlled trial; Volume 90, Issues 1–2, 1 February 2001, Pages 83–90

- ↑ Kandziora F, Pflugmacher R, Scholz M, Schnake K, Putzier M? Khodadadyan-Klostermann C, Haas NP. Posterior stabilization of subaxial cervical spine trauma: indications and techniques. Injury 2005 Jul;36 Suppl 2:B36-43. Review

- ↑ Fehlings MG, Cooper PR, Errico TJ. Posterior plates in the management of cervical instability: long-term results in 44 patients. Journal of neurosurgery. 1994 Sep 1;81(3):341-9.

- ↑ Gross R. et al; Knowledge to action: a challenge for neck pain treatment; J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2009 May;39(5):351-63 (LOE:5)