Case Study- Late Onset Moderate Alzheimer's Disease

Abstract[edit | edit source]

Client Characteristics/comorbidity: Mary Johnston is an 80-year-old female diagnosed with Late-Onset Alzheimer’s Disease (LOAD) disease who lives alone and has been referred by her family physician to be assessed to improve balance following a fall that occurred 6-months prior causing her to require hip surgery. This fracture could have been attributed with her osteoporosis that she was diagnosed with after the fall had occurred.

Disease Phenotype/examination Findings: Moderate stage, with cognitive symptoms as well as limiting physiological symptoms such as forgetfulness, irritability, and problems with gait. A complete subjective, objective analysis was collected and limitations in balance, gait speed, and strength were noticed.

Outcome measures: The outcome measures used were the BERG balance scale (BBS), the 30-second sit to stand test (30CST), and the 6 minute walking test (6 MWT).

Problem List: The problems obtained were structured around the international classification of functioning, disability and health (ICF) model and focused on the limitations in balance, gait speed, and strength.

Clinical Hypothesis/impression: The patient’s diagnosis is poor mobility and function due to general lower limb weakness along with a mild deficit in balance which is related to the LOAD diagnosis. She has a fair prognosis with physiotherapy and could benefit from it by focusing on muscle strength, aerobic endurance and walking speed to help improve ADLs, participate in social activities outside the home and maintain as much independence for as long as possible.

Intervention: Resistance strength exercises (60 minutes, 3 sets of 15 reps per exercise using a medium resistance elastic band 3 days a week for 4 months and an aerobic walking program was prescribed (45 minutes per session, 4 times a week, for 4 months at an intensity of 40% heart rate reserve (HRR) and slowly progress up to 80% HRR). As there is conflicting evidence incorporating virtual reality in the treatment of patients with moderate Alzheimer’s, there may be a benefit to including it into treatment if the technology and resources are readily available. However, there may or may not be any benefit to doing so.

Outcome: The patient had a clinically significant improvement in their BBS of 3 points. She can now perform 2 full sit-to-stand during the 30-second sit-to-stand without using her hands for support. However, we cannot conclude whether this improvement is clinically significant due to the lack of research in this population. Finally, she had no improvement in distance covered, but demonstrated an increase in confidence during the test.

Common healthcare professionals involved in care: It was recommended to refer out to an occupational therapist, neuropsychologist, and a social worker.

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Alzheimer's is a form of dementia that impacts cognitive functions such as memory, reasoning, and conduct. As the disease progresses, the symptoms become increasingly debilitating and disrupting everyday activities[1]. Literature shows that multimodal exercise with a combination of resistance, aerobic, balance, flexibility around 60 minutes a day, 2-3 days a week is effective in improving various aspects of physical functioning[2]. Additionally, strong evidence was found to support the use of physical exercise in improving strength, step length, balance, mobility and walking endurance for mild to moderate cognitive impairment and dementia population[2].

This case study depicts Mary Johnston, a patient with Late-onset Alzheimer’s Disease in the moderate stage, with cognitive symptoms including forgetfulness, confusion, depression, irritability, difficulty with planning and problem-solving. Her physical symptoms include problems with gait and increased risk of falls. This case study aims to document the changes in the patient’s chief complaints throughout her participation in a 4-month physiotherapy program.

Client Characteristics[edit | edit source]

Demographic Information: Mary Johnston is an 80-year-old female who was diagnosed with Late-Onset Dementia, specifically Alzheimer’s disease (LOAD) at the age of 75. She is recently widowed and has lived alone in her 2-storey condominium for 2 years. Her adult children live nearby and visit her frequently. She finds herself becoming more frequently agitated as she is having increasing difficulty recalling objects and how to do actions[3]. Since Mary is prone to wandering, in the past she would frequently wander out of her house. 5 months ago, during a wandering incident, she experienced a fall outside of her home and fractured her left hip. Since then, she went through a rehab program and currently uses a 1-point cane for ambulation and currently receives care from a support care worker service to help her around the house with cleaning and meal prepping, and is rarely mobilized outside of the home. She has been taking donepezil for 3 years now to assist with memory deficits and verbal learning, but has only noticed a slight improvement in symptoms[4].

Disease Phenotype: Mary's Alzheimer's disease is a late-onset form of dementia due to Alzheimer’s (LOAD). It is in the moderate stage, with cognitive symptoms including forgetfulness, confusion, depression, irritability, difficulty with planning and problem-solving. Physical symptoms include problems with gait and increased risk of falls. She also experiences occasional disorientation as she is prone to wandering outside of her own home.

Examination Findings[edit | edit source]

Subjective:

- Has difficulties remembering what she did on the weekends, conversations, and names of people

- Gets confused about where she is or how she arrived to certain places

- She has troubles expressing herself verbally and emotionally

- She becomes frustrated, anxious, and depressed based on her inability to recall information and/or complete tasks of daily living

- Struggles to complete daily grooming tasks and cooking her own meals

- Wanders often and gets lost easily

- Has issues keeping her balance and holds onto objects around the house while ambulating (walls, furniture, etc.)

- Pain VAS: 1/10 at rest in the left hip, with gait: 3/10.

- Precautions/Contraindications: short term memory with confusion in occasions, risk of agitation.

Observation:

- Exaggerated kyphosis in the thoracic spine → rounded back

- Forward head posture.

- Difficulty with fine motor skills including pen holding when filling out a form.

- Slight disorientation & confusion at times during assessment.

- While standing, stands with a wide base of support

AROM:

- Limited IR and ER in the shoulder

- Limited Shoulder flexion bilaterally.

- Limited left hip extension and abduction.

- Limited knee flexion

- All other ROM is within normal limits.

PROM:

- Limited left hip extension and abduction

- All other joints within functional ranges.

- Normal tone

Resisted Muscle Testing (MMT):

| Hip Extension | Hip abduction | Knee flexion | Knee extension | Ankle Plantarflexion | Ankle dorsiflexion |

| L: 3/5

R: 3+/5 |

L: 3/5

R: 3+/5 |

L: 3+/5

R: 4-/5 |

L: 3+/5

R: 4-/5 |

L: 4-/5

R: 4-/5 |

L: 3-

R: 3 |

Coordination Tests:

- Finger to nose: symmetrical and smooth bilaterally

- Heel to shin: symmetrical and smooth bilaterally

- Alternate movement of hands & feet: symmetrical and able to increase speed.

Respiratory function:

- Respiratory rate: 19 bpm

- Apical breathing pattern observed

- Modified Borg RPE

- At rest: 1/10

- With exertion: 3/10

- Dyspnea scale

- At rest: 0/10

- With exertion: 2/10

Outcome measures:

- BERG balance test: Final score of 38/56

- 30-second Sit to Stand: Score 0 due to the need to use her arm while performing the test.

- 6 MWT: She covered 160 m in 6 minutes using a one-point cane.

Gait:

- Tested with the use of a gait aid (single-point cane)

- Slower gait speed of 0.61 m/s

- Decreased stride length

- Normal cadence

- Wide base of support

- Decreased arm swing

- Forward leaning posture

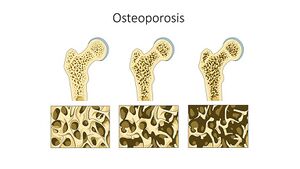

Comorbidity - Osteoporosis: Comorbidity is defined as the presence of more than one distinct condition in an individual[5]. One study found that people with Alzheimer's Disease are more prone to falling, sustaining a hip fracture, and to have osteoporosis[6]. Additionally, Mary is a 75-year-old woman who has undergone the normal changes that occur as a result of menopause. Menopause causes hormonal changes, specifically a rapid decrease in estrogen which normally helps maintain bone density[7]. Therefore, osteoporosis may have been a contributing factor to Mary's hip fracture when she fell outside.

Problem List

- Body Structure and Function: Mary has poor gait and balance due to reduced activity levels, poor cognition and attention.

- Activity Limitations: Due to her lack of lower extremity muscular endurance and strength, Mary has difficulty with activities of daily living such as dressing, grooming, and preparing meals. Specifically, standing for long periods of time to shower, as well as preparing meals.

- Participation Restrictions: Mary feels socially isolated and has limited ability to participate in bingo. This is due to her inability to maintain attention and dual task to ambulate in a safe and effective way to cross the major intersection at Senior Centre.

Clinical Hypothesis/Impression[edit | edit source]

Physiotherapy Diagnosis: Mary's physiotherapy diagnosis is poor mobility and function due to general lower limb weakness along with a mild deficit in balance which is related to the LOAD diagnosis.

Prognosis: Mary has a fair prognosis due to the progressive nature of her primary diagnosis of LOAD. Mary has the finances to afford to pay for support and physiotherapy treatment, as well as has close family support when needed. The family has already been able to adapt the home environment to Mary’s needs so that she can continue living at home. However, she recently experienced a fall and a fracture while out in the community, putting her at risk for decreased mobility status and atrophy. Additionally, she has cognitive issues affecting her memory, mood and activity of daily living (ADLs), which may impact the effectiveness of physiotherapy treatment.

Based on these factors, she could still benefit from physiotherapy by focusing on muscle strength, aerobic endurance and walking speed to help improve ADLs, participate in social activities outside the home and maintain as much independence for as long as possible. Referrals out to occupational therapy, neuropsychology, and a social worker could all assist in the holistic treatment of her condition. Although Mary’s condition has developed into a moderate cognitive decline, there are many things she can still participate in to slow the progression of the disease.

Intervention[edit | edit source]

Goals

Short-term goals:

- Mary will be provided with strengthening exercises to enable her to balance on one leg to improve her BERG score to reduce risk of falls and subsequent injury within four weeks

- Through a prescribed muscular strengthening program, Mary will increase her lower limb strength and endurance to foster confidence towards independence of bADLs, specifically self-grooming tasks within four weeks.

- Improve Mary’s gait speed through gait specific exercises as measured through the 6MWT, thus improving Mary’s mobility and ability to travel to the Senior’s Center for Bingo, within four weeks.

Long-term goals:

- Mary will increase her overall score using the BERG Balance Scale by five points (to reach minimal detectable change) through a variety of balance and strengthening exercises provided by and progressed with the physical therapist within four months.

- Mary will continue to work on strengthening exercises focused on static loading to develop the endurance required to prepare her own meals in a timely manner, thus reducing the stress that Mary feels while cooking and reducing her care-giver burden within four months.

- Improve Mary’s confidence to participate in Bingo at the Senior’s Center through combining exercises related to gait to improve her speed, thus increasing her likelihood to engage in Bingo night within four months.

Intervention program:

- resistance strength exercise program x both upper and lower body x 60 minutes/ 3 sets of 15 reps per exercise x targeting the chest, biceps, triceps, shoulder, knee extensors, abductor and adductor muscles, and calf muscles x elastic band of a medium resistance level x 3 days/week for 4 months[2][8].

- The resistance strength exercise has been shown to not only increase the participants’ strength, but also improve participants’ balance[2].

- aerobic walking exercise program x 45 minutes per session x 4 times/week x for four months.

- She would be instructed to walk at an intensity of 40% of her heart rate reserve (HRR) (this would be educated to her as walking at a moderate intensity) and we would slowly progress her up to 80% HRR as she progressed[9].

- This exercise could be conducted on a treadmill to ensure a safe environment.

- Included to target Mary’s walking speed so that she can participate in her bingo activities.

Innovative Technology-mediated tools to enhance the approach to intervention:

As indicated through the case-study, balance issues can be a main physiotherapy problem associated with those with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s onset Dementia (AD)[10]. Especially since those diagnosed with AD are at a higher risk for falls and resulting hip fractures, further increasing their dependence on others for ADLs and mobilization[6]. Thus, balance training should be an important factor in physical therapy for those with a LOAD diagnosis. Specific innovative technology that can be implemented to supplement traditional balance training is virtual reality (VR).

A systematic review and meta-analysis completed by Zhu et al., 2021[11] analyzed the effectiveness of VR on cognition, balance and gait for those with a mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s dementia. This study determined that VR had a moderate effect size on cognition and motor function overall, but did not have a significant effect on visuospatial ability or gait. Additionally, VR had a significant impact on those with a mild cognitive impairment versus a non-significant impact on those with AD, suggesting that moderate to severe cognitive impairment associated with AD may inhibit the positive effects of VR on balance. Thus, it would be ideal to implement VR balance training in those who are at risk of developing AD progressed from a MCI. Finally, this study found that semi-immersive or fully-immersive VR is more effective than low-immersive VR. Another systematic review completed by Yi et al., 2022[12] confirmed these results, echoing that moderate-immersive VR improves body balance in those with AD. Therefore, due to the conflicting evidence of the effectiveness of VR in those with moderate AD, supplementing traditional physiotherapy treatment with VR may be beneficial, provided that the resources are available and the patient can tolerate it well.

VR may be an effective approach as it involves both immersive and interactive components[11]. Immersion of a patient in a virtual reality environment acts as a safer method to performing rehabilitation exercises in the community, along with the added ability of providing multiple forms of sensory feedback through external equipment to replicate a real-world environment[11]. This has been demonstrated physiologically through increased EMG in the right arm while participants observed a virtual arm made to move with the person’s body, and through an increase in heart rate to the virtual projected hole in the ground[13][14].

For further reading regarding VR, head over to: Virtual Reality As a Memory Aid in Cognitive Impaired Older Adults

Outcome[edit | edit source]

Following Mary’s initial assessment, it was determined that she would receive four months of physiotherapy care at home to address her lower body strength, balance and gait speed deficits. After the first four weeks, there were little changes in Mary’s functional status. It actually gave her some light discomfort such as muscle soreness. However, after 4 months of following an aerobic walking and a resistance exercise program, Mary’s main functional status including lower body muscle strength, balance and her speed of gait has changed despite still having some problems with cognition issues or memories. According to the Berg Balance Scale administered after the treatment program, her score improved from 38 to 41/56. This indicates she is still at greater risk of falling, but her score is shown to be clinically significant improvement[15]. Additionally, she can now perform 2 full sit-to-stand during the 30-second sit-to-stand without using her hands for support, which indicates that she is currently below average[16]. A conclusion cannot be made on whether this is a clinically significant improvement due to the lack of research on this population. Finally, she had no improvement in distance covered, but demonstrated an increase in confidence during the test. Based on her progress and improvements over the past four months Mary should continue physiotherapy treatment as needed to help manage the progression of the musculoskeletal, postural, and gait impairments secondary to LOAD.

A few adverse effects of this exercise program could be falling, increased fatigue, headaches and experiencing an increase of pain[17][18]. If there was an adverse event with the patient, the exercise program could be adapted in a few ways. Firstly, to reduce falls risk, we could recommend that the patient could perform aerobic exercise on a treadmill to ensure a safe environment and to reduce risk of falls when exercising if they have the means to do so. However, if they do not have the resources or funds to use a treadmill, Mary could do standing marches and progress up to walking as she progresses. If the intensity of the program were to be too much for the patient, we would lower the total minutes of exercise to 30 minutes per program, as this time was still shown to have a significant improvement for participants post-exercise program[2]. As well, we would reduce the HHR of the aerobic exercise back down to 40% until she could build back up her tolerance for exercise, and both the strengthening and aerobic protocol could be reduced to 2x/week if needed and still have a significant effect on the patient’s outcomes[2].

Common healthcare professionals involved in care:

- Occupational Therapists: provide everyday tools and strategies for improving independence and completing bADLs and iADLs implementing social and exercise interventions to improve sleep, and utilizing errorless learning techniques to help prompt ADLs[19].

- Neuropsychologist: plays a main role in the diagnosis and assessment of symptoms in those with LOAD[20]. A common assessment tool used to assess the cognition of older adults with LOAD is the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA)[20].Additionally, the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) is widely used to assess cognitive functions such as attention, memory, and language[20].

- Social workers: can provide assistance with bADLs and education for outsourcing common care-giver duties to family members and people close to the person affected by LOAD. They can also provide emotional support as well as physical support by helping with the home duties that the patient is unable to do. For example, they could help with getting dressed, day care, or social activities[21]. Lastly, they can work within the legal field to aid with appointing a guardian for Alzheimer's Disease patients and with placement issues regarding moving a community dwelling Alzheimer's Disease patients with to an institution. [22]

Discussion[edit | edit source]

People diagnosed with Late-Onset Alzheimer’s Disease (LOAD) face many challenges that must be addressed through an interdisciplinary team of health care professionals. As physiotherapists our scope of practice aims to improve a patient’s mobility, function, and quality of life through interventions related to modalities, manual therapy, and exercise prescription. These troubles are only a fraction of what people with LOAD struggle with on a daily basis. In addition to deficits in mobility and exercise adherence, people with LOAD have negative effects on memory, thinking, and behaviours. It is important to consider these declines in cognition in people with LOAD and to refer out appropriately. In addition to physiotherapy, a common health-care team required when treating people with LOAD would commonly include an occupational therapist, neuropsychologist, and a social worker. Each member of the team will provide distinct treatment and care that would benefit a person diagnosed with LOAD. In addition to the interdisciplinary health-care team, education provided to care-givers and family members can be extremely beneficial in reducing the day-to-day burden of care that people with LOAD feel.

In conclusion, people with LOAD need a multidisciplinary team of healthcare professionals, each with individualized goals to help facilitate the maintenance of function, and provide strategies to reduce the burden-of-care that people with LOAD experience. Communication between the team as well as other care-givers such as family members is absolutely necessary to provide optimal care in people with LOAD.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ What is Alzheimer’s? [Internet]. Alzheimer’s Disease and Dementia. [cited 2023 May 10]. Available from: https://alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/what-is-alzheimers

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Lam FM, Huang MZ, Liao LR, Chung RC, Kwok TC, Pang MY. Physical exercise improves strength, balance, mobility, and endurance in people with cognitive impairment and dementia: a systematic review. Journal of Physiotherapy. 2018 Jan 1;64(1):4–15.

- ↑ O’Sullivan SB, Schmitz TJ, Fulk G, editors. Physical Rehabilitation 7th - ed. Philadelphia (US): F. A. Davis Company. 2019a. p. 1161

- ↑ O’Sullivan SB, Schmitz TJ, Fulk G, editors. Physical Rehabilitation 7th - ed. Philadelphia (US): F. A. Davis Company. 2019b. p. 675

- ↑ Valderas JM, Starfield B, Sibbald B, Salisbury C, Roland M. Defining Comorbidity: Implications for Understanding Health and Health Services. Ann Fam Med. 2009 Jul;7(4):357–63.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Weller I, Schatzker J. Hip fractures and Alzheimer’s disease in elderly institutionalized Canadians. Annals of Epidemiology. 2004 May 1;14(5):319–24.

- ↑ Cauley JA, Seeley DG, Ensrud K, Ettinger B, Black D, Cummings SR. Estrogen replacement therapy and fractures in older women. Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. Ann Intern Med. 1995 Jan 1;122(1):9–16.

- ↑ López-Ortiz S, Valenzuela PL, Seisdedos MM, Morales JS, Vega T, Castillo-García A, et al. Exercise interventions in Alzheimer’s disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Ageing Res Rev. 2021 Dec;72:101479.

- ↑ Lam FM, Huang MZ, Liao LR, Chung RC, Kwok TC, Pang MY. Physical exercise improves strength, balance, mobility, and endurance in people with cognitive impairment and dementia: a systematic review. Journal of Physiotherapy. 2018 Jan 1;64(1):4–15.

- ↑ Suttanon P, Hill KD, Said CM, LoGiudice D, Lautenschlager NT, Dodd KJ. Balance and Mobility Dysfunction and Falls Risk in Older People with Mild to Moderate Alzheimer Disease. American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation. 2012 Jan;91(1):12–23.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Zhu S, Sui Y, Shen Y, Zhu Y, Ali N, Guo C, et al. Effects of Virtual Reality Intervention on Cognition and Motor Function in Older Adults With Mild Cognitive Impairment or Dementia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2023 May 6];13. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnagi.2021.586999

- ↑ Yi Y, Hu Y, Cui M, Wang C, Wang J. Effect of virtual reality exercise on interventions for patients with Alzheimer’s disease: A systematic review. Frontiers in Psychiatry [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2023 May 6];13. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.1062162

- ↑ Meehan M, Razzaque S, Insko B, Whitton M, Brooks FP. Review of four studies on the use of physiological reaction as a measure of presence in stressful virtual environments. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback. 2005 Sep;30(3):239–58.

- ↑ Slater M, Perez-Marcos D, Ehrsson HH, Sanchez-Vives MV. Towards a digital body: the virtual arm illusion. Front Hum Neurosci. 2008;2:6.

- ↑ Berg KO, Wood-Dauphinee SL, Williams JI, Maki B. Measuring Balance in the Elderly: Validation of an Instrument. Canadian Journal of Public Health / Revue Canadienne de Sante’e Publique. 1992;83:S7–11.

- ↑ Rikli RE, Jones CJ. Functional Fitness Normative Scores for Community-Residing Older Adults, Ages 60-94. Journal of Aging and Physical Activity. 1999 Apr 1;7(2):162–81.

- ↑ Faieta JM, Devos H, Vaduvathiriyan P, York MK, Erickson KI, Hirsch MA, et al. Exercise interventions for older adults with Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis protocol. Systematic Reviews. 2021 Jan 4;10(1):6.

- ↑ Henley DB, Sundell KL, Sethuraman G, Schneider LS. Adverse events and dropouts in Alzheimer’s disease studies: What can we learn? Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2015;11(1):24–31.

- ↑ Smallfield S, Heckenlaible C. Effectiveness of Occupational Therapy Interventions to Enhance Occupational Performance for Adults With Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Major Neurocognitive Disorders: A Systematic Review. The American journal of occupational therapy. 2017;71(5):p1–7105180010.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Rascovsky K. A Primer in Neuropsychological Assessment for Dementia [Internet]. Practical Neurology. Bryn Mawr Communications; 2016 [cited 2023 May 11]. Available from: https://practicalneurology.com/articles/2016-july-aug/a-primer-in-neuropsychological-assessment-for-dementia

- ↑ Social care professionals | Alzheimer’s Society [Internet]. [cited 2023 May 11]. Available from: https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/get-support/help-dementia-care/social-care-professionals

- ↑ Werner P, Doron I (Issi). The Legal System and Alzheimer’s Disease: Social Workers and Lawyers’ Perceptions and Experiences. Journal of Gerontological Social Work. 2016 Aug 17;59(6):478–91.