Biopsychosocial Considerations for Clinicians when ordering MRI for Low Back Pain

Top Contributors - Ho Man Hayden Lui, William Brothwell, Cindy John-Chu, Theo Elsegood, Kim Jackson and Vidya Acharya

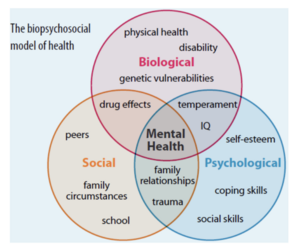

Biopsychosocial Model[edit | edit source]

George Engel’s 1977 Biopsychosocial Model [1] was introduced to negate previous medical or biological models thus, encompassing social and psychological factors of illness.

- Bio – the physical, how does the condition present?

- Psychological – what are the patient’s beliefs about the pain? What was their psychological state before the illness or injury?

- Social – what does this person do for work? What is their family situation? What is their support network? What are their commitments? What external factors could have caused this condition to present?

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI):[edit | edit source]

- In Layman’s terms, an MRI scanner is a large and powerful magnet which gives us an image of the patient. The MRI is able to carry out this function because of the presence of hydrogen atoms found all over the body. It takes a detailed "picture" of these atoms and computes them into an accurate representation of the particular body region it is scanning. Hydrogen atoms are useful to the MRI device because they consist of a single proton with a large magnetic moment.

- In the device, magnetic field is created by magnets causing resonance from each proton in the hydrogen atom then the machine can obtain the proton’s position. Since 75% of our bodies are made from water molecules, MRI imaging can capture precise and detailed images. Each type of cell however emits a distinct signal, which allows the identification of bones, joints, muscle, and cartilage.

Low Back Pain[edit | edit source]

Low back pain (LBP) - pain of the lumbar and sacral spine, may result from a myriad causes. It is termed chronic when low back pain continues for 12 weeks or more, because of an initial injury or an underlying cause of acute back pain.

Chronic low back pain (CLBP):

- Develops in 5-10% of lower back pain cases.

- The second leading cause of disability worldwide.

- Significant influence of psychological factors e.g., anxiety/depression.[2]

- Increased prevalence with age, where individuals over 50 are 3-4 times more likely to have CLBP than those aged 18-30.

- Diagnosis of chronic low back pain is commonly affirmed from a patient's history.

MRI and LBP[edit | edit source]

Imaging findings, such as disc degeneration, facet arthropathy, and disc herniations, have been attributed as causative factors for LBP. However, in many cases, these findings are asymptomatic. [3] Nevertheless, in some cases, it can be symptomatic and highly painful. If this is missed in the acute phase, it could also become a contributing factor to CLBP. Less than 10% of cases are diagnosed with MRI.

Literature portrays MRI as the optimal imaging choice and is considered the gold standard diagnostic tool for detecting a range of spinal pathologies. [4] Currently, for every ten patients presenting to primary care with LBP, one receives advanced imaging. [5]

Biological Considerations[edit | edit source]

Risks Factors and Contradictions of MRI Imaging[edit | edit source]

- Magnetic Implants

Dangerous effects on patients with magnetic foreign body implants include: projectile effect, twisting, burning artifacts, and implant device malfunction. For example, in populations with pacemakers or other ferromagnetic implants, the strong magnetic forces will draw these objects towards the centre of the machine and can result in them becoming dangerous projectiles. In addition, the radio frequency coils used in the MRI machines can cause tissue heating, which is exacerbated in the presence of implants. [6] Yet, it must be noted that more recently, MRI conditional implantable electronic devices are becoming widely available. [7]

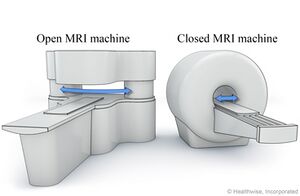

- Individual Fears

For patients who experience claustrophobia, a discussion should be had with the clinician, explaining the procedure and the equipment used. In more serious cases patients may need to be sedated to complete the procedures. [9] Another option would be to use an open MRI, as shown in the image.

- Sound Levels

MRI scanners are loud machines, which reach levels of up to 100db or more which can be harmful to the human ear. All patients and staff present in the MRI room during the examination must be offered headphones or hearing protection. [10]

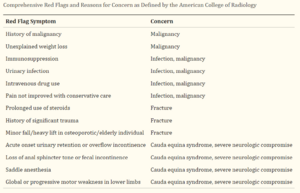

Clinical Guidelines and Red Flags[edit | edit source]

Guidelines from the American College of Physicians discourage the routine use of MRI in patients with CLBP. They recommend MRI to be reserved for patients with severe or progressive neurological symptoms, like those with signs of lumbar radiculopathy or spinal stenosis. [11]

Additionally, decisions for diagnostic imaging may be prompted by further presenting red flags. Patients presenting with such symptoms may indicate serious pathologies and are shown to benefit from imaging. [12] Comprehensive red flags and the related reasons for concern can be seen in definitions from the American College of Radiology as shown in the image. [13]

Short and Long Term Outcomes[edit | edit source]

The above recommendations are backed by literature from the Lancet, which found no benefits either short term (<3 months) or long term (6-12 months) when comparing immediate lumbar imaging to usual care processes without any imaging. [14]

Abnormalities found on MRI have little prognostic value, for both symptoms and levels of patient disability. [15] When considering long term outcomes, very few abnormalities or degenerative changes can indicate worse outcomes. [16] This is seen in patients followed up 13 years after their MRI, with changes identified on their MRI not associated with any worsening outcomes. In patients with CLBP who undergo MRI, 52-82% will present with degenerative changes, however very few of these patients will go on to have surgical intervention in the long term. [17]

Symptomatic Populations[edit | edit source]

Timing of MRIs:

The evidence suggests that in patients with symptomatic lumbar spinal disorders, there are no benefits when comparing early and late MRIs. It must be noted that for both study populations, the resulting clinical interventions were very similar between the two groups. A slightly higher Aberdeen LBP score was noted in the group receiving the early MRI, however it must be left up to clinicians in their own healthcare systems to make a judgement as to whether this benefit justifies the additional cost. [18]

Decision to Imaging:

When comparing the results of symptomatic patients having an MRI against those who don't go on to have an image, the only difference is the level of diagnostic confidence. As before, there were no differences observed in either diagnostic or therapeutic decision-making. It is interesting to note that both groups saw a statistically significant increase in both diagnostic and therapeutic confidence from participants when comparing figures from trial entry and follow-up. [19] This evidence highlights the confidence of patients in their treatment, despite the group they were in. In agreement with the previous studies presented, this study reiterates that without the presence of serious pathological indicators, treatment decisions will be very similar with or without the results of an MRI.

Furthermore, when considering patients with a first-time episode of LBP it is highly unlike that MRI will identify a new structural change directly associated with the patients' new pain symptoms. It has also been found that there was no change in the incidence of new MRI findings in populations who experienced minor trauma, compared to those who experienced an idiopathic onset of their symptoms. [20]

Iatrogeneic Consequences:

In populations having LBP as a result of their work, the effects of early MRI are shown to be detrimental to their treatment, displaying iatrogenic effects. It was found that approximately 22% of patients who had an early MRI displayed greater disabilities with added burdens of higher medical costs than those who did not. It must be noted that these results were significant, with outcomes maintained across the varying severity of LBP cases. [21]

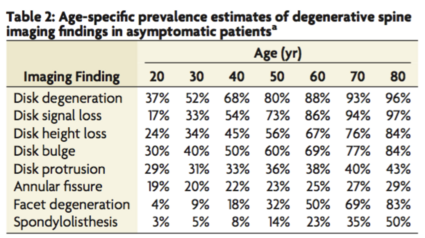

Asymptomatic populations[edit | edit source]

Existing Findings:

When considering ordering imaging for patients presenting with LBP, it is important to understand the prevalence of common findings in asymptomatic populations. Given the strength of MR imaging, it is common for images to show spinal degeneration. [23] This table highlights how common these changes can be, especially in those patients in the 50+ age group.

These research findings indicate that the changes identified on MRI scans are often part of the natural process of aging, rather than part of a serious pathological presentation which requires intervention, hence why these changes are identified in the vast majority of asymptomatic patients. [22]

Clinical decisions cannot be solely based on the results of MR imaging findings. Clinicians must interpret these results in the full context of the patients' biopsychosocial presentations.

Psychological Considerations[edit | edit source]

Clinician Beliefs[edit | edit source]

Usefulness in Diagnosing:

Some clinicians believe clinical presentations from diagnostic imaging are useful in locating sources of low back pain. As so, clinicians can be fearful of missing serious pathologies and thus choosing to utilise diagnostic imaging. Primary care clinicians have stated referring patients for imaging even though it may not be necessary at times, partly to reduce risks of legal repercussions and to manage patient expectations. [24]

Even though diagnostic imaging can be a useful component in a physiotherapy assessment, it should not be used as the sole indicator for pathologies. Such imaging results should be blended into a management plan to assist in better detecting barriers to functional impairments and in turn undergo safe and appropriate interventions. [25]

Fear-Avoidance Practices:

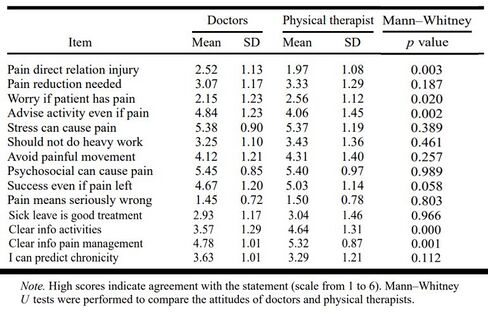

Some clinicians are shown to possess adverse beliefs regarding pain and movements. These beliefs from healthcare professionals, especially on low back pain, were examined through a modified questionnaire with fear-avoidance scores from physiotherapists shown below: [26]

- Over 33% believed reduced pain to be a prerequisite for returning to activities.

- Over 66% reported that they would advise patients to avoid painful movements

- Over 25% believed sick leaves as a good treatment for low back pain.

These statistics correlate with relatively high mean statement scores from physiotherapists, showing adverse practices of advising to avoid painful movements (mean score=4.31), avoiding heavy work (mean score=3.43), and believing sick leave to be a good treatment (mean score=3.04).

With clinicians practicing with fear-avoidance beliefs, this can inherently impact patients as well and reaffirm any similar existing beliefs. Psychological factors including fear-avoidance are associated with increased risks of developing pain and disability in chronic LBP patients. [27] Hence, clinicians should take a patient-centred approach and include psychological interventions as well to facilitate management. Methods such as Cognitive Functional Therapy are shown to be beneficial with large and sustained improvements up to 52 weeks for chronic LBP patients with considerably lower costs. [28]

Biomedical vs Biopsychosocial:

Clinicians have also expressed a lack of awareness and knowledge of the most up-to-date back pain recommendations, with these guidelines not routinely applied by healthcare professionals in primary care. [29][30] This in turn dictates many treatment orientations, with clinicians approaching low back pain patients with a biomedical model instead of the biopsychosocial model. [31]

A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies has shown physiotherapists focusing mainly on physical pathologies and addressing symptoms of impairment during sessions. They reported disliking treating difficult patients and had poor outcome expectancies for these treatments. Physiotherapists generally felt unconfident in treating with a biopsychosocial model, having low self-efficacy and presuming assessment of psychosocial factors was not part of their roles. [32]

This shows a preference for physiotherapists to treat biological issues. Yet, rather than practicing with strong biomedical focuses, physiotherapists should embrace the idea that functional impairments and pain may be influenced by other psychosocial factors. [33] A SR supports this by reporting a biopsychosocial approach is superior to a biomedically focused approach in chronic low back pain. [34]

Patient Demands[edit | edit source]

Persuasive Natures:

Patients will often demand imaging and are likely to be insistent as they rarely consider possibilities for harm. This can potentially sway clinicians even though they may be aware of the consequences of unnecessary imaging and optimal approaches to be taken instead. Physiotherapists are shown to be easily influenced, with them likely to make clinical decisions based on therapist-patient relationships and patient characteristics, such as the perceived “passivity of patients”.[35] Patient demands and expectations can exist for a plethora of reasons, with main ones explored below.

Evidence for Proof:

Patients with low back pain believe pathoanatomical findings on diagnostic imaging can provide credible explanations to support their chronic experiences of pain to be real. They hope for these realistic evidence to provide a sense of reassurance and relieve to patients who may have felt stigmatized with their symptom presentations. They are shown to deeply value such results and often chooses to use the information in convincing other medical professionals, family, friends, and colleagues. [36] Hence, patients are shown to have strong desires to receive imaging for a specific diagnosis, hoping to legitimize their experiences of pain by providing information about the causes, underlying pathologies, and to rule out potential sinister causes.

Treatment Expectations:

Research data also shows up to half of all LBP patients expected some form of imaging from healthcare providers[37], further suggesting patients can be persistent in demanding diagnostic imaging. A 2020 systematic review showed numerous qualitative interview studies to have found patients initiating referrals for imaging if it was not suggested by the clinician.[38] An account from a patient by Rhodes et al described asking for a referral continuously until it was accepted.[39]

Additionally, with LBP often recurring for prolonged periods,[40] some patients also believed that imaging can identify the cause better than physical exams from clinicians and in turn facilitate a more tailored approach to treatment. Expectations for tailored approaches include personalized information about self-management strategies and the available support services related to both healthcare and occupational issues. [41]

Example of a LBP patient demanding an MRI.[42]

Contextual Factors[edit | edit source]

Policies & Evidence:

Following on from clinicians not being aware of up-to-date guidelines, if institutional policies regarding imaging are not aligned with the latest evidence, then clinicians may also face confusion when deciding to order diagnostic imaging. This may be exacerbated in recent times, with many International Consensus Conferences being halted due to the global pandemic and thus potentially not catching up to new research.

Staffing Barriers:

Furthermore, staffing may also be scarce and to avoid a backlog of patients, clinicians must keep sessions quick simultaneously in maintaining a satisfactory turnover rate to see all patients assigned. A quote from a clinician in a qualitative study encompasses this perfectly: “Sometimes I find myself referring a patient for X-ray in order to clear the waiting room and allow myself two minutes of breathing time. Meanwhile the patient keeps quiet, while I write the referral. Sometimes you find yourself doing this and it goes against any reasoning or logic”. [43]

Social Considerations[edit | edit source]

Waiting Times:

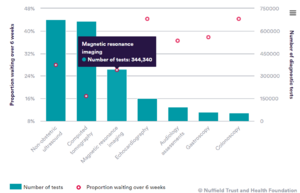

The NHS has a national target for non-urgent (such as LBP patients who present without red flags/radiculopathy/spinal stenosis or progressive neurological symptoms) or routine cases to receive their MRI within a 6-week period from the initial referral, and urgent cases (such as LBP red flags) are targeted to be seen within a 2-week timeframe. [44]

In 2023, the current average estimated waiting time is 6-18 weeks for an outpatient MRI scan. It is estimated that 26% of outpatients in 2023 have waited longer than 6 weeks for an MRI. [45] Waiting lists for outpatient MRI scans have significantly increased in recent years, with the number of patients waiting six weeks plus increasing from 2.5% in August 2019, to 28.1% in August 2020. [17] COVID-19 is one of the root causes of this backlog alongside funding cuts to nationwide healthcare services. The prioritisation of urgent over non-urgent cases post COVID-19 has resulted in further growth in waiting times. At the end of January 2022, the NHS estimated there to be 280,139 patients awaiting an MRI nationally. [45]

Costs & Funding:

Currently in the NHS, there is a lack of funding and deep rooted staffing issues [46]. With inadequate funding, clinicians may be faced with less individual patient contact time. Large wait times have resulted in clinicians being required to see a high threshold of patients daily. This can lead to insufficient time in explaining and justifying non-imaging approaches. This was evidenced in a qualitative study that conducted focus group interviews with clinicians. The clinicians reported one of the key reasons for regularly not conversing with patients about imaging and why a scan is not always required, was due to the lack of time. [47]

Imaging has direct and indirect costs. A meta-analysis found that low back MRI scans have an association with unnecessary increases in spinal surgeries, despite there being no clear differences in patient outcomes. [48] This resulted in increased healthcare costs despite no clear difference in benefit, with conservative treatments being more cost effective with similar patient outcomes.

One study found that 80% of patients with LBP would undergo radiography if they had the choice, despite no benefits of routine imaging. [49] Patients often misinterpret positive MRI findings as more severe and specific pathologies, even when these findings are clinically unrelated to the presenting symptoms. This leads to further patient requests for medical interventions resulting in increased healthcare costs. [50]

Key Considerations for Clinicians[edit | edit source]

- Acute patients presenting with red flag indicators for serious pathology, spinal stenosis, radiculopathy or progressive neurological symptoms should be sent for an MRI. [51] Clinicians should follow guidelines when considering the management of patients with LBP, considering when it is best appropriate to order MRI.

- There are a range of LBP guidelines that clinicians can refer to such as; NICE guidelines for the UK [52], ACP guidelines for the USA [53], national guidelines of Denmark [54] and the national guidelines of Belgium [55]. All of these guidelines discuss the role that MRI has in the management of LBP patients.

- Clinicians should be aware that all guidelines recommend against the use of routine MRI. Most guidelines recommend that MRIs should only be ordered when red flags are present or when the imaging results are likely to alter the patient's treatment and management pathway. Two guidelines recommend imaging for patients with LBP that persists beyond 4-6 weeks. [51]

- Positive MRI findings often do not correlate to patient's symptoms. 52-82% of patients will have degenerative changes [17] and disc bulges are seen in up to 97% of asymptomatic patients. [56]

- Early MRIs (within the first month) for LBP often result in greater periods of disability for patients when compared to those who receive negative findings or no imaging, leading to increased healthcare costs. [57]

- Clinicians should offer education and explanation that MRI is not always required. Patients should be informed that imaging for LBP usually does not help find a cause of pain or guide treatment. The treatment for most LBP is the same whether MRI is used or not, those who have unnecessary imaging are more likely to have a delayed recovery. [56]

Below is a snippet from a patient education booklet Understanding My Low Back Pain, this can be used to assist patients with their understanding of why imaging may not be necessary.

Future[edit | edit source]

Currently, there are still considerable unknowns regarding what alternatives to imaging can convey cLBP diagnoses in a satisfactory manner for patients. Future research and discussions should target this area to develop clear strategies and guidelines for clinicians to explain.

An important step forward is to train physiotherapists in improving confidence and skills to address complex LBP. It is beneficial to identify and manage psychosocial issues in additional to biological complaints for holistic patient-centred care.

By being aware of these underlying considerations, physiotherapists can become better advocates and prevent stigmatisation of LBP patients regarding these wider factors presenting as part of their experiences. [58]

Conclusion[edit | edit source]

Clinicians should consider a multitude of factors relating to the biopsychosocial model to make informed decisions when ordering an MRI for patients with symptomatic LBP. There is wide evidence to suggest that MRI findings often do not align with patients' clinical symptoms.

With patients with non-serious pathological findings, such as degenerative disc changes and disk bulges, clinicians should be aware that early positive MRI findings have associations with increased and prolonged periods of disability for this population. It is common for these asymptomatic MRI findings to increase in prevalence with age.

It is crucial that clinicians have adequate awareness and understanding of the national guidelines and pathways when considering the use of imaging. Clinicians should educate patients about why imaging is not always necessary and why it might cause further biopsychosocial complications, including further disability, unnecessary treatments, and increased costs. Hopefully, by addressing patients holistically, this can in turn empower them to break negative cycles of debilitation caused by LBP.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Engel GL. The need for a new medical model: A challenge for biomedicine. Science. 1977;196(4286):129–36. doi:10.1126/science.847460

- ↑ Allegri M, Montella S, Salici F, Valente A, Marchesini M, Compagnone C, et al. Mechanisms of low back pain: A guide for diagnosis and therapy. F1000Research. 2016;5:1530. doi:10.12688/f1000research.8105.2

- ↑ Rao D, Scuderi G, Scuderi C, Grewal R, Sandhu SJ. The use of imaging in management of patients with low back pain. Journal of Clinical Imaging Science. 2018;8:30. doi:10.4103/jcis.jcis_16_18

- ↑ Kim G-U, Chang MC, Kim TU, Lee GW. Diagnostic modality in spine disease: A Review. Asian Spine Journal. 2020;14(6):910–20. doi:10.31616/asj.2020.0593

- ↑ Beattie PF, Meyers SP. Magnetic Resonance Imaging in low back pain: General principles and clinical issues. Physical Therapy. 1998;78(7):738–53. doi:10.1093/ptj/78.7.738

- ↑ Ghadimi M, Sapra A. Magnetic resonance imaging contraindications. InStatPearls [Internet] 2022 May 8. StatPearls Publishing.

- ↑ Stecco A, Saponaro A, Carriero A. Patient safety issues in magnetic resonance imaging: state of the art. La radiologia medica. 2007 Jun 1;112(4):491-508.

- ↑ image available at: https://myhealth.alberta.ca/Health/aftercareinformation/pages/conditions.aspx?hwid=ug6705

- ↑ Thorpe S, Salkovskis PM, Dittner A. Claustrophobia in MRI: the role of cognitions. Magnetic resonance imaging. 2008 Oct 1;26(8):1081-8.

- ↑ Sammet S. Magnetic resonance safety. Abdominal radiology. 2016 Mar;41:444-51.

- ↑ Sheehan NJ. Magnetic resonance imaging for low back pain: indications and limitations. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases [Internet]. 2009 Dec 9;69(01):7–11.

- ↑ Lancaster B, Goldman J, Kobayashi Y, Gottschalk AW. When is imaging appropriate for a patient with low back pain?. Ochsner Journal. 2020 Sep 21;20(3):248-9.

- ↑ Patel ND, Broderick DF, Burns J, Deshmukh TK, Fries IB, Harvey HB, Holly L, Hunt CH, Jagadeesan BD, Kennedy TA, O’Toole JE. ACR appropriateness criteria low back pain. Journal of the American College of Radiology. 2016 Sep 1;13(9):1069-78.

- ↑ Chou R, Fu R, Carrino JA, Deyo RA. Imaging strategies for low-back pain: systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet. 2009 Feb;373(9662):463–72.

- ↑ McNee P, Shambrook J, Harris EC, Kim M, Sampson M, Palmer KT, et al. Predictors of long-term pain and disability in patients with low back pain investigated by magnetic resonance imaging: A longitudinal study. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2011 Oct 14;12(1).

- ↑ Ract I, Meadeb JM ., Mercy G, Cueff F, Husson JL ., Guillin R. A review of the value of MRI signs in low back pain. Diagnostic and Interventional Imaging. 2015 Mar;96(3):239–49.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Udby PM, Ohrt-Nissen S, Bendix T, Brorson S, Carreon LY, Andersen MØ. The Association of MRI Findings and Long-Term Disability in Patients With Chronic Low Back Pain. Global Spine Journal. 2020 May 12;11(5):633–9.

- ↑ Gilbert FJ, Grant A, Maureen, Vale L, Campbell MK, Scott NW, et al. Low Back Pain: Influence of Early MR Imaging or CT on Treatment and Outcome—Multicenter Randomized Trial. Radiology. 2004 May 1;231(2):343–51.

- ↑ Maureen, Gilbert FJ, Andrew J, Grant A, Wardlaw D, Valentine NW, et al. Influence of Imaging on Clinical Decision Making in the Treatment of Lower Back Pain. 2001 Aug 1;220(2):393–9.

- ↑ Carragee E, Alamin T, Cheng I, Franklin T, van den Haak E, Hurwitz E. Are first-time episodes of serious LBP associated with new MRI findings? The Spine Journal. 2006 Nov;6(6):624–35.

- ↑ Webster BS, Cifuentes M. Relationship of Early Magnetic Resonance Imaging for Work-Related Acute Low Back Pain With Disability and Medical Utilization Outcomes. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2010 Sep;52(9):900–7.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Brinjikji W, Luetmer PH, Comstock B, Bresnahan BW, Chen LE, Deyo RA, et al. Systematic Literature Review of Imaging Features of Spinal Degeneration in Asymptomatic Populations. American Journal of Neuroradiology. 2014 Nov 27;36(4):811–6.

- ↑ Sąsiadek MJ, Bladowska J. Imaging of degenerative spine disease–the state of the art. Adv Clin Exp Med. 2012;21(2):133-42.

- ↑ Sharma S, Traeger AC, Reed B, Hamilton M, O’Connor DA, Hoffmann TC, Bonner C, Buchbinder R, Maher CG. Clinician and patient beliefs about diagnostic imaging for low back pain: a systematic qualitative evidence synthesis. BMJ open. 2020 Aug 1;10(8):e037820.

- ↑ Prabhu and Ahmed T. Imaging Practice around the World in Physiotherapy. Ann Yoga Phys Ther. 2017; 2(1): 1017. Ann Yoga Phys Ther - Volume 2 Issue 1 - 2017

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Linton SJ, Vlaeyen J, Ostelo R. The back pain beliefs of health care providers: are we fear-avoidant?. Journal of occupational rehabilitation. 2002 Dec;12:223-32.

- ↑ Yang J, Lo WL, Zheng F, Cheng X, Yu Q, Wang C. Evaluation of cognitive behavioral therapy on improving pain, fear avoidance, and self-efficacy in patients with chronic low back pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain Research and Management. 2022 Mar 19;2022.

- ↑ Kent P, Haines T, O'Sullivan P, Smith A, Campbell A, Schutze R, Attwell S, Caneiro JP, Laird R, O'Sullivan K, McGregor A. Cognitive functional therapy with or without movement sensor biofeedback versus usual care for chronic, disabling low back pain (RESTORE): a randomised, controlled, three-arm, parallel group, phase 3, clinical trial. The Lancet. 2023 May 2.

- ↑ Williams CM, Maher CG, Hancock MJ, McAuley JH, McLachlan AJ, Britt H, Fahridin S, Harrison C, Latimer J. Low back pain and best practice care: a survey of general practice physicians. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2010 Feb 8;170(3):271-7.

- ↑ Piccoliori G, Engl A, Gatterer D, Sessa E, in der Schmitten J, Abholz HH. Management of low back pain in general practice–is it of acceptable quality: an observational study among 25 general practices in South Tyrol (Italy). BMC Family Practice. 2013 Dec;14:1-8.

- ↑ Foster NE, Delitto A. Embedding psychosocial perspectives within clinical management of low back pain: integration of psychosocially informed management principles into physical therapist practice—challenges and opportunities. Physical therapy. 2011 May 1;91(5):790-803.

- ↑ Gardner T, Refshauge K, Smith L, McAuley J, Hübscher M, Goodall S. Physiotherapists’ beliefs and attitudes influence clinical practice in chronic low back pain: a systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Journal of physiotherapy. 2017 Jul 1;63(3):132-43.

- ↑ Bishop A, Foster NE, Thomas E, Hay EM. How does the self-reported clinical management of patients with low back pain relate to the attitudes and beliefs of health care practitioners? A survey of UK general practitioners and physiotherapists. PAIN®. 2008 Mar 1;135(1-2):187-95.

- ↑ Kamper SJ, Apeldoorn AT, Chiarotto A, Smeets RJ, Ostelo RW, Guzman J, van Tulder M. Multidisciplinary biopsychosocial rehabilitation for chronic low back pain: Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2015 Feb 18;350.

- ↑ Corbett M, Foster N, Ong BN. GP attitudes and self-reported behaviour in primary care consultations for low back pain. Family practice. 2009 Oct 1;26(5):359-64.

- ↑ Toye F, Seers K, Hannink E, Barker K. A mega-ethnography of eleven qualitative evidence syntheses exploring the experience of living with chronic non-malignant pain. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2017 Dec;17(1):1-1.

- ↑ Lim YZ, Chou L, Au RT, Seneviwickrama KM, Cicuttini FM, Briggs AM, Sullivan K, Urquhart DM, Wluka AE. People with low back pain want clear, consistent and personalized information on prognosis, treatment options and self-management strategies: a systematic review. Journal of physiotherapy. 2019 Jul 1;65(3):124-35.

- ↑ Taylor S, Bishop A. Patient and public beliefs about the role of imaging in the management of non-specific low back pain: a scoping review. Physiotherapy. 2020 Jun 1;107:224-33.

- ↑ Rhodes LA, McPhillips-Tangum CA, Markham C, Klenk R. The power of the visible: the meaning of diagnostic tests in chronic back pain. Social science & medicine. 1999 May 1;48(9):1189-203.

- ↑ da Silva T, Mills K, Brown BT, Pocovi N, de Campos T, Maher C, Hancock MJ. Recurrence of low back pain is common: a prospective inception cohort study. Journal of physiotherapy. 2019 Jul 1;65(3):159-65.

- ↑ Hall AM, Aubrey-Bassler K, Thorne B, Maher CG. Do not routinely offer imaging for uncomplicated low back pain. bmj. 2021 Feb 12;372.

- ↑ Patient with Back Pain who requests an MRI. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cJLuxDbBs1w [last accessed 18/05/2023]

- ↑ Hall AM, Scurrey SR, Pike AE, Albury C, Richmond HL, Matthews J, Toomey E, Hayden JA, Etchegary H. Physician-reported barriers to using evidence-based recommendations for low back pain in clinical practice: a systematic review and synthesis of qualitative studies using the Theoretical Domains Framework. Implementation Science. 2019 Dec;14(1):1-9.

- ↑ Diagnostic Test Waiting Times. QualityWatch; 2023 [cited 2023 May 19]. Available from: https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/resource/diagnostic-test-waiting-times

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 Wood J. Your guide to MRI waiting Times - NHS vs private. 2023 [cited 2023 May 17]. Available from: https://practiceplusgroup.com/knowledge-hub/mri-waiting-times/

- ↑ Buchan J, Charlesworth A, Gershlick B, Seccombe I. The Health Foundation; 2019 [cited 2023 May 17]. Available from: https://www.health.org.uk/sites/default/files/upload/publications/2019/A%20Critical%20Moment_1.pdf

- ↑ Espeland A, Baerheim A. Factors affecting general practitioners’ decisions about plain radiography for back pain: Implications for classification of guideline barriers – a qualitative study. BMC Health Services Research. 2003;3(1). doi:10.1186/1472-6963-3-8

- ↑ Chou R, Fu R, Carrino JA, Deyo RA. Imaging strategies for low-back pain: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Governance: An International Journal. 2009;14(3). doi:10.1108/cgij.2009.24814cae.009

- ↑ Kendrick D. Radiography of the lumbar spine in primary care patients with low back pain: Randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2001;322(7283):400–5. doi:10.1136/bmj.322.7283.400

- ↑ Mahmud MA, Webster BS, Courtney TK, Matz S, Tacci JA, Christiani DC. Clinical management and the duration of disability for work-related low back pain. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2000;42(12):1178–87. doi:10.1097/00043764-200012000-00012

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 Oliveira CB, Maher CG, Pinto RZ, Traeger AC, Lin C-WC, Chenot J-F, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of non-specific low back pain in primary care: An updated overview. European Spine Journal. 2018;27(11):2791–803. doi:10.1007/s00586-018-5673-2

- ↑ Overview: Low back pain and sciatica in over 16s: Assessment and management: Guidance [Internet]. NICE; 2020 [cited 2023 May 18]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng59

- ↑ Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, McLean RM, Forciea MA. Noninvasive treatments for acute, subacute, and chronic low back pain: A clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2017;166(7):514. doi:10.7326/m16-2367

- ↑ Stochkendahl MJ, Kjaer P, Hartvigsen J, Kongsted A, Aaboe J, Andersen M, et al. National clinical guidelines for non-surgical treatment of patients with recent onset low back pain or lumbar radiculopathy. European Spine Journal. 2017;27(1):60–75. doi:10.1007/s00586-017-5099-2

- ↑ van Wambeke P, Desomer A, Jonckheer P, Depreitere B. The Belgian national guideline on low back pain and radicular pain: Key roles for rehabilitation, assessment of rehabilitation potential and the PRM specialist. European Journal of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine. 2020;56(2). doi:10.23736/s1973-9087.19.05983-5

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 Hall AM, Aubrey-Bassler K, Thorne B, Maher CG. Do not routinely offer imaging for uncomplicated low back pain. BMJ. 2021; doi:10.1136/bmj.n291

- ↑ Mahmud MA, Webster BS, Courtney TK, Matz S, Tacci JA, Christiani DC. Clinical management and the duration of disability for work-related low back pain. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2000;42(12):1178–87. doi:10.1097/00043764-200012000-00012

- ↑ Flynn TW, Smith B, Chou R. Appropriate use of diagnostic imaging in low back pain: a reminder that unnecessary imaging may do as much harm as good. journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy. 2011 Nov;41(11):838-46.