Whiplash Associated Disorders: Difference between revisions

Rachael Lowe (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

'''Top Contributors''' - {{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}} | '''Top Contributors''' - {{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}} | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

== Search strategy<br> == | |||

Databases: Pubmed, Pedro, WebOfScience, emedicine, VUBmedical library, ScienceDirect, Google scholar<br>Keywords: ‘WAD range of motion’ and ‘WAD physical therapy’ and ‘prevalence WAD’ and ‘cause WAD’ and ‘prognostic factors WAD’ and ‘WAD diagnosis’ and ‘Whiplash injuries’ and ‘characterization WAD’<br><br> | |||

== Definition/description<br> == | |||

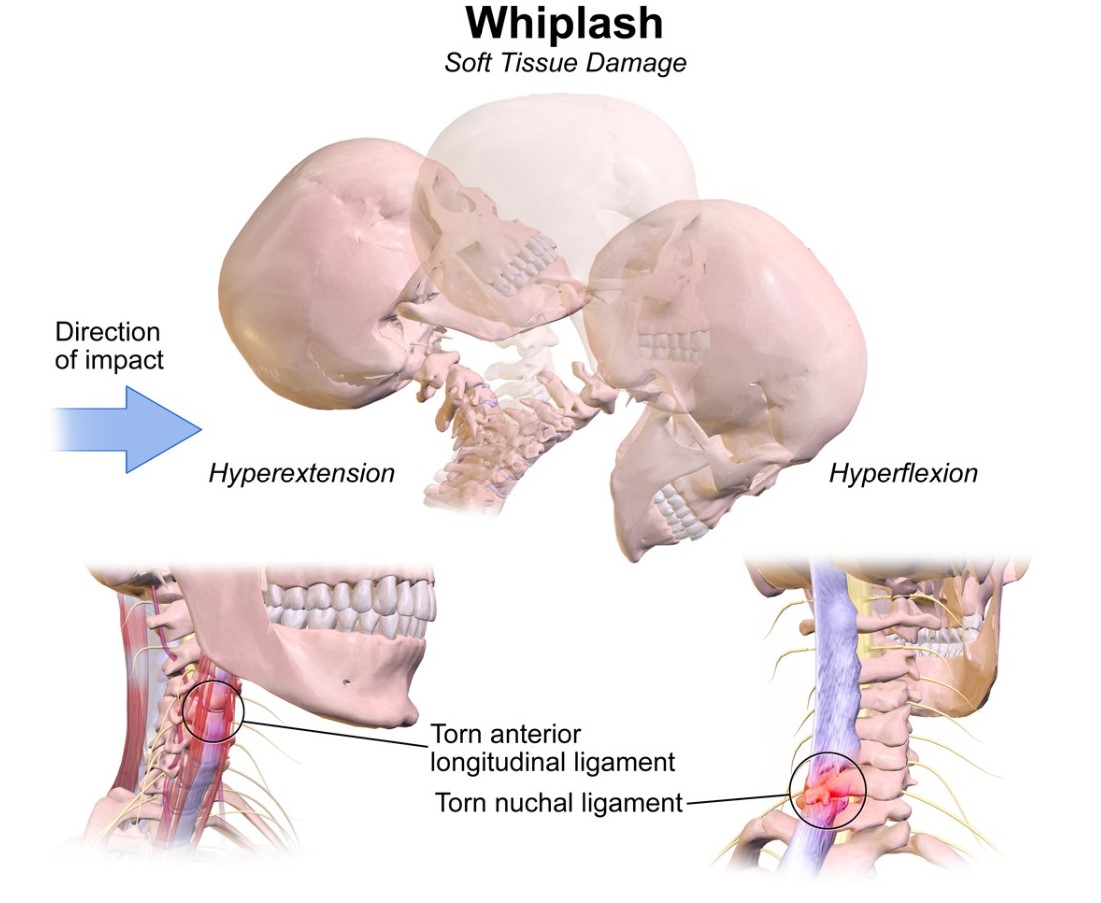

Whiplash is an acceleration-deceleration mechanism of energy transfer to the neck. It may result from rear-end or side-impact motor vehicle collisions, but can also occur during diving or other or following other types of falls. The impact may result in bony or soft-tissue injuries (whiplash-injury), which in turn may lead to a variety of clinical manifestations called Whiplash-Associated Disorders (WAD). Spitzer WO et al (1995) [58 [LOE:2C]]<br>It is estimated that about 30% to 50% of patients who sustain a symptomatic whiplash injury are going to report chronic, and potentially more widespread symptoms, which may be classified as WAD. [59 [LOE:2C]]<br> <br>WAD is a good example of a medical condition where there is often an apparent disconnect between the magnitude of injury and the magnitude of disability. [59 [LOE:2C]]<br> <br>According to the Quebec Task Force of WAD there is a clinical grading of whiplash injuries. [74 [LOE:2C]] This will be explained in point 5. Characteristics/Clinical Presentation.<br><br> | |||

== Clinically Relevant Anatomy<br> == | == Clinically Relevant Anatomy<br> == | ||

Whiplash and whiplash associated disorders (WAD) | Whiplash and whiplash-associated disorders (WAD) affect variable areas of the cervical spine, depending on the force and direction of impact as well as many other factors. [12 [LOE:5]]<br>Chronic WAD implicates neuromusculoskeletal lesions, including dysfunctions of [29 [LOE:3B]] [35 [LOE:4] : | ||

*the cervical zygapophyseal joints | |||

*[[Atlanto-axial_joint|Atlanto-axial joint]] | |||

*[[Atlanto-occipital_joint|Atlanto-occipital joint]] | |||

*[[Intervertebral_disc|intervertebral disc]] | |||

*cartilaginous endplates | |||

*muscles | |||

*ligaments:<br> | |||

#[[Alar_ligaments|Alar ligament]] | |||

#[[Anterior_atlanto-axial_ligament|Anterior atlanto-axial ligament]]<br> | |||

#[[Anterior_atlanto-occipital_ligament|Anterior atlanto-occipital ligament]] | |||

#[[Apical_ligament|Apical ligament]] | |||

#[[Anterior_longitudinal_ligament|Anterior longitudinal ligament]] | |||

#[[Transverse_ligament_of_the_atlas|Transverse ligament of the atlas]] | |||

*vertebrae | |||

#[[Atlas|Atlas]] | |||

#[[Axis|Axis]] | |||

*nervous systems structures: | |||

#nerve roots | |||

#spinal cord | |||

#brain | |||

#sympathetic nervous system | |||

*[[Temporomandibular_joint|Temporomandibular joint]] | |||

*[[Acromioclavicular_Joint|Acromioclavicular joint]] | |||

*the peripheral vestibular system | |||

*the cervical arteries | |||

#internal carotid | |||

#vertebral artery | |||

<br>Anatomic causes of pain can be any of these tissues, with the strain injury resulting in secondary edema, hemorrhage, and inflammation.<br><br> | |||

== Epidemiology/etiology<br> == | |||

The risk that patients develop WAD after an accident with acceleration-deceleration mechanism of energy transfer of the neck depends on a variety of factors. <br>In a study by Holm et al, it was demonstrated that one of the key factors for developing WAD is the severity of the impact. However, it is difficult to obtain objective evidence to confirm this. [33 [LOE:1A]]<br>According to the study by D. Obelieniene et al., there is evidence that neck pain present before the accident is a risk factor for acute neck pain after collision. [38 [LOE:1A]]<br>In addition, some people are more likely to develop WAD than others., In particular, women seem to be slightly more at risk of developing WAD. Age is also important; younger people (18-23) are more likely to file insurance claims and/or are at greater risk of being treated for WAD. [10 [LOE: 3B]] [39 [LOE:2A]]<br> <br>There are several prognostic factors that determine the evolution of WAD and the likelihood that it will evolve into chronic pain. <br> | |||

*According to Carstensen et al., the following factors: pre-collision self-reported unspecified pain, high psychological distress, female gender and low educational level predicted future self-reported neck pain. He also demonstrated that self-reported characteristics before the collision are important for recovery. [11 [LOE: 5]] | |||

*In another study, prognostic factors were: no postsecondary education, female gender, history of previous neck pain, baseline neck pain intensity greater than 55/100, presence of neck pain at baseline, presence of headache at baseline, catastrophising, WAD grade 2 or 3, and no seat belt in use at the time of collision. [80 [LOE:1A]] | |||

*If the patient was out of work before the accident, sick-listed, or had social assistance, this can also be associated with a negative evolution following whiplash trauma. Illness notification before the accident can also be associated with neck pain in the future. [11 [LOE : 5]] | |||

*Baseline disability had the strongest association with chronic disability, but psychological and behavioural factors were also important. [81 [LOE :2B]]<br> | |||

JD Cassidy and Scholton-Peeters demonstrated in their studies that 14 to 42 % of the whiplash patients are at risk of developing chronic complaints (longer than 6 months) and that 10 % of those have constant severe pain. The number of people worldwide who suffer from chronic pain is between 2 and 58 %, but lies mainly between 20 and 40%. [38 [LOE :1A]] <br>If patient still have symptoms 3 months after the accident they are likely to remain symptomatic for at least two years, and possibly for much longer. [39 [LOE:2A]]<br> <br>Based on several studies, we can conclude that the prevalence of WAD depends on the country or the part of the world. For example, the prevalence per 100,000 inhabitants is of 70 in Quebec, 106 in Australia and 188–325 in the Netherlands.<br>But according to the study of Versteegen, in which he studied patients with neck pain following a car accident in the last ten years, the prevalence per 100,000 inhabitants increased significantly from to 3.4 in 1974 to 40.2 in 1994. A study by Richter also shows an increase in prevalence of 20% between 1985 and 1997. The increase is due in part to a higher number of cars on the roads, which in turn can lead to more accidents. However, this increase in prevalence is also due to the fact that there is a greater public awareness of WAD and therefore those affected are more likely to consult their doctor and therefore the number of patients seeking healthcare for whiplash is on the rise. [33 [LOE:1A]] [38 [LOE:1A]] <br><br> | |||

[[Image:Whiplash Injuries.jpg|border|center]] | |||

<br> | |||

== Characteristics/Clinical Presentation == | |||

Whiplash-associated disorders, is a complex condition with varied disturbances in motor, sensorimotor, and sensory functions and psychological distress. [20 [LOE:5][21 [LOE:2A]] The most common symptoms are sub-occipital headache and/or neck pain that is constant or motion-induced. [25 [LOE:2B]] There may be up to 48 hrs delay of symptom onset from the initial injury.[17 [LOE:2A]] <br> | |||

*Motor dysfunction: | |||

#One of the most common clinical characteristics is a restricted range of motion of the cervical spine. This finding may reflect underlying disturbances in motor function due to the initial peripheral nociceptive input caused by injured anatomical cervical structures. Further research of such potential mechanisms in WAD is necessary. [20 [LOE:5]] [12] | |||

#Another characteristic is altered patterns of muscle recruitment in both the cervical spine and shoulder girdle regions. This is clearly shown to be a feature of chronic WAD. [20 [LOE:5]] [61 [LOE :2A]] [62 [LOE :2A]] [68 [LOE :2B]] | |||

#Mechanical cervical spine instability [17 [LOE:2A]] | |||

*Sensorimotor dysfunction | |||

#Loss of balance | |||

#Disturbed neck influenced eye movement control [17 [LOE:2A]] | |||

#Sensorimotor dysfunction is greater in patients who also report dizziness due to the neck pain. [20 [LOE:5]] [74 [LOE :2C]] [67 [LOE :2B] | |||

*Sensory dysfunction: sensory hypersensitivity to a variety of stimuli<br> | |||

#Psychological distress<br> | |||

#Posttraumatic stress [20 [LOE:5]]<br> | |||

#Concentration and memory problems [74 [LOE :2C]] [67 [LOE :2B]<br> | |||

#Anxiety [67 [LOE :2B]]<br> | |||

#Depression [67 [LOE :2B] is common in WAD patients. There are different types we can distinguish:<br>■ Initial depression: this can be associated with greater neck and low back pain severity, numbness/tingling in arms/hands, vision problems, dizziness, fracture, [46 [LOE:2B]]<br>■ Persistent depression: this can be associated with older age, greater initial neck and low back pain, post-crash dizziness, anxiety, numbness/tingling, vision and hearing problems [46 [LOE:2B]]<br> | |||

*Degeneration cervical muscles<br> | |||

#Neck stiffness [74 [LOE :2C]] [67 [LOE :2B]<br> | |||

#Fatty infiltrate may be present in the deep muscles in the suboccipital region and the multifidi may account for some of the functional impairments such as: Proprioceptive deficits, Balance loss, Disturbed motor control of the neck [20 [LOE:5]] [25 [LOE:2B]] [61 [LOE :2A]] [62 [LOE :2A]] [68 [LOE :2B]] [74 [LOE :2C]] [67 [LOE :2B]<br> | |||

<br> The following symptoms may also occur [67 [LOE :2B] [17 [LOE:2A]]:<br> | |||

*Tinnitus | |||

*Malaise | |||

*Disequilibrium/Diziness | |||

*Thoracic, temporomandibular, facial, and limb pain | |||

It is important to carry out thorough spinal and neurological examinations in patients with WAD to screen for delayed onset of the cervical spine instability or myelopathy. [17 [LOE:2A]] see point 9 examination. <br>Whiplash can be an acute or chronic disorder. In acute whiplash, symptoms last no more than 2-3 months, while in chronic whiplash symptoms last longer than three months. Patients with acute WAD experience widespread pressure hypersensitivity and reduced cervical mobility. [23 [LOE :2B]] Various studies indicate that there can be a spontaneous recovery within 2-3 months [28 [LOE:2B]]. According to the Quebec Task Force of WAD (QTF-WAD), 85% of the patients recover within 6 months.[5 [LOE:1A]]<br>In addition, according to a follow-up study by Crutebo et al. (2010), some symptoms were already transient at baseline and symptoms such as neck pain, reduced cervical range of motion, headache, and low back pain, decreased further over the 6 months period. They also investigated the prevalence of depression and found that at baseline this was around 5% in both women and men, whereas posttraumatic stress and anxiety were more common in women (19.7% and 11.7%, respectively) compared to men (13.2% and 8.6%). The majority of all reported associated symptoms were mild at both baseline and during follow-up. [16 [LOE:2B]]<br>According to the QTF-WAD there is a clinical grading of whiplash injuries. [74 [LOE:2C]]<br><br> | |||

===== QTFC (Quebec Task Force Classification)<br> ===== | ===== QTFC (Quebec Task Force Classification)<br> ===== | ||

The Quebec Task Force was a task force sponsored by a public insurer in Canada. | The Quebec Task Force was a task force sponsored by a public insurer in Canada. This Task Force developed recommendations regarding the classification and treatment of WAD, which were used to develop a guide for managing whiplash in 1995.[58 [LOE :2C]] An updated report was published in 2001. Each of the QTFC grades corresponds to a specific treatment recommendation. [61 [LOE:2A]]<br> | ||

{| width="404" cellspacing="1" cellpadding="1" border="2" align="center" | {| width="404" cellspacing="1" cellpadding="1" border="2" align="center" | ||

| Line 72: | Line 160: | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

'''MQTFC (Modified Quebec Task Force Classification) ''' | '''MQTFC (Modified Quebec Task Force Classification) '''[61 [LOE:2A]]<br> | ||

<br> | |||

{| cellspacing="1" cellpadding="1" border="1" align="center" style="width: 596px; height: 1318px;" | {| cellspacing="1" cellpadding="1" border="1" align="center" style="width: 596px; height: 1318px;" | ||

| Line 187: | Line 271: | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

<br> | In addition, a classification based on subjective complaints and formal testing of self-estimated cognitive impairment, divided attention, and speed of information processing was suggested by Radanov and co-workers [48 [LOE :4]] : <br> | ||

*Lower cervical spine syndrome (LCS) accompanied by cervical and cervicobrachial pain. | |||

*Cervicoencephalic syndrome (CES) characterized by headache, fatigue, dizziness, poor concentration, disturbed accommodation, and impaired adaptation to light intensity. | |||

In comparison with the QTF classification, this system of classification incorporates<br>neuropsychological symptoms. [65 [LOE :2C]<br><br> | |||

== Differential Diagnosis<br> == | |||

Soft tissue lesions:<br> | |||

*Cervical radiculopathy [13 [LOE :3B]] | |||

*Cervical myelopathy [6 [LOE :5]] | |||

*[[Cervical_Arterial_Dysfunction|Vascular abnormality of cervical structures]] | |||

Fibromyalgia and psychogenic causes: [6 [LOE :5]]<br> | |||

*Psychogenic pain disorder | |||

*Facticious disorder | |||

*Malingering [22 [LOE:4]] | |||

Mechanical lesions:<br> | |||

*Cervical herniated disk [6 [LOE :5]]<br> | |||

*Mechanical Neck Disorder [31 [LOE:3B]] | |||

Inflammatory:<br> | |||

*Inflammatory rheumatologic disease [6 [LOE :5]] | |||

*[[Polymyalgia_Rheumatica|Polymyalgia Rheumatica]] [6 [LOE :5]] | |||

Metabolic: [6 [LOE :5]]<br> | |||

*[[Osteoporosis|Osteoporosis]] | |||

*Cervical osteoarthritis | |||

Infective:<br> | |||

*Infection or [[Osteomyelitis|osteomyelitis]] [6 [LOE :5]] | |||

Malignancy:<br> | |||

*Tumor or malignancy of cervical spine [6 [LOE :5]] | |||

Adjacent pathology:<br> | |||

*Shoulder or acromioclavicular disease [6 [LOE :5]] | |||

Other:<br> | |||

*[[Cervicogenic_Headache|Cervicogenic Headache]] [79 [LOE :5]] | |||

*[[Referred_Pain|Referred pain]] from cardiothoracic structures | |||

*[[Traumatic_Brain_Injury|Traumatic Brain Injury]] [22 [LOE :4]]<br><br> | |||

== Diagnostic Procedures == | == Diagnostic Procedures == | ||

[[ | <u>Clinical diagnosis</u><br>The diagnosis of WAD remains clinical and the mechanism of the injury must be elicited. [49 [LOE:4]] Based on the clinical presentation of the patient, WAD can be diagnosed. [61 [LOE:2A]] According to Rondriguez et al. (2004), there are no specific neuropsychological tests that can diagnose WAD. [49 [LOE:4]] However, there are several psychological symptoms, as described above in section 5. Characteristics/Clinical Presentation, that are associated with WAD. In addition, a whiplash profile has been developed with high scores on subscales of somatisation, depression and obsessive compulsive behaviour in patients with WAD. [10 [LOE:3B]] | ||

<u>Radiographic diagnosis</u><br>According to Yalda et al (2008), the injury is most often not identified radiologically in the acute phase [82 [LOE:1A]] . The most common radiographic findings are [19 [LOE:2A]]: <br> | |||

*preexisting degenerative disease | |||

*slight loss of the normal lordotic curve of the cervical spine | |||

*kyphotic angle at the time of injury → due to hypermobility and secondary to muscle spasm | |||

MRI is not indicated at the time of initial presentation because of the high false positive results. [75 [LOE:3B]] | |||

CT and MRI are generally used by patients with suspected spinal cord or disc injury, fracture or ligamentous injury. They may also be indicated in patients with long term persistent arm pain, neurological deficits, or clinical signs of nerve root compression [75 [LOE :3B]] | |||

X-ray should be routinely used for the patients with WAD grade III and IV. If the X-ray gives positive results for fracture or dislocation, the patient should be immediately referred to an emergency department or to a specialist surgeon. [35 [LOE :4]] | |||

[[Canadian_C-Spine_Rule|Canadian C-Spine Rule]] (CCR) is an algorithm to determine the necessity for cervical spine radiography in alert and stable patients with trauma and cervical spine injury. [66 [LOE:2B]]<br><br> | |||

== Outcome measures<br> == | |||

[[Neck_Disability_Index|Neck Disability Index]] [5 [LOE :1A]] [78 [LOE :5]] [83 [LOE :1A]]<br>[[Visual_Analogue_Scale|Visual Analogue Scale]] (VAS) [5 [LOE :1A]] [83 [LOE :1A]]<br>The Whiplash Activity a participation List (WAL) [60 [LOE :2C]]<br>Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand (DASH) in persistent Whiplash [53 [LOE:2C]]<br>[[SF-36|SF-36]] [2 [LOE :2B]], [83 [LOE :1A]]<br>Functional Rating Index [83 [LOE :1A]]<br>The Self-Efficacy Scale [83 [LOE :1A]]<br>The Coping Strategies Questionnaire [83 [LOE :1A]]<br>[[Patient_Specific_Functional_Scale|Patient-Specific Functional Scale]] [83 [LOE :1A]]<br>Core Whiplash Outcome Measure [83 [LOE :1A]]<br>The Kessler Psychological Distress Scale [83 [LOE :1A]]<br>The Impact of Event Scale [83 [LOE :1A]]<br><br> | |||

== Examination<br> == | |||

Before examination, it is crucial to obtain anamnesis. History taking is important during all visits for the treatment of WAD patients, no matter which grade it is.<br>The history should include information about: <br> | |||

*date of birth, gender, occupation, number of dependants, marital status | |||

*prior history of neck problems (including previous whiplash) | |||

*prior history of physiological disturbances | |||

*prior history of long-term problems (injury and illness) | |||

*current psychosocial problems (family, job-related, financial) | |||

*symptoms (location + time of onset) | |||

*circumstances of injury (sport, motor vehicle;..), mechanism of injury, position of person when accident occurred, type of vehicle | |||

*results of an assessment using tools to measure general psychological state and pain: | |||

#General Health Questionnaire (CHQ)<br> | |||

#Visual Analogue pain Scale | |||

#Neck Disability index | |||

[84 [LOE :5]] | |||

Physical examination is required to identify signs and symptoms. The examination procedure for patients with WAD is similar to the examination of the cervical spine. WAD can be divided into 4 grades according to the QTF-WAD. The findings of the examination will allow the grade to be determined.[63 [LOE:1A]]<br> <br>The physical examination should begin with an inspection and palpation. During palpation, stiffness and tenderness of the muscles may be observed. These physical symptoms are present in grade 1, 2 and 3. Trigger points may also be observed in grade 2 and 3 WAD. The number of active trigger points may be related to higher neck pain intensity, the number of days since the accident, higher pressure pain hypersensitivity over the cervical spine, and reduced active cervical range of motion.<br>[23 [LOE:2B]]<br> <br>The next step in the examination is ROM testing. In grade 1 WAD, there are no physical signs, so there will be no decreased ROM. In grades 2 and 3, a decreased ROM can be identified by testing the neck flexion, extension, rotation and 3D movements.<br>[63 [LOE:1A]] [23 [LOE:2B]]<br> <br>To distinguish grade 3 from grade 2, neurological examination is needed. Patients with grade 3 have symptoms of hypersensitivity to a variety of stimuli. These can be subjectively reported by patients, and may include allodynia, high irritability of pain, cold sensitivity, and poor sleep due to pain.<br>Objectively, the results of the neurological examination are hyporeflection, decreased muscles force and sensory deficits in dermatome and myotome. These responses may occur independently of psychological distress. Other physical tests for hypersensitivity include pressure algometers, pain with the application of ice, or increased bilateral responses to the brachial plexus provocation test.<br>It is important to know that these neurological symptoms do not necessarily indicate peripheral nerve compression and may be a reflection of altered central nociceptive processes.<br>[63 [LOE:1A]]<br>These findings may be important for the differential diagnosis of acute whiplash injury. A poorer outcome is generally predicted in patients with higher initial pain and disability as well as hypersensitivty (e.g. cold hyperalgesia).<br>[63 [LOE:1A]] [64 [LOE :2B]]<br> <br>To identify grade 4 WAD, which is a fracture or dislocation, medical imaging is needed. A simple test for including or excluding a fracture is to smite with the ulnar side of the fist on the spine. If there is a severe pain, one can speak of a fracture.<br> <br>“In recent years, there has also been extensive research undertaken demonstrating movement, muscle, and motor control changes in the neck and shoulder girdles of patients with neck pain, including WAD. Study findings include inferior performance on tests of motor control involving the cervical flexor, extensor and scapular muscle groups when compared to asymptomatic control participants; changes in muscle morphology of the cervical flexor and extensor muscles; loss of strength and endurance of cervical and scapular muscle groups; and sensorimotor changes manifested by increased joint re-positioning errors, poor kinaesthetic awareness, altered eye movement control, and loss of balance. Detailed information on the clinical assessment of cervical motor function is available elsewhere. The rationale for the evaluation of such features is to plan an individualised exercise program for each patient based on the assessment findings.” M. Sterling (2014). Physiotherapy management of whiplash-associated disorders (WAD). [63 [LOE:1A]]<br> <br>Cervical zygapophysial is in 50% of the WAD patients a symptom-giving structure. The cervical zygapophysial joint pain must therefore also be examined. [54 [LOE : 1A]]<br><br> | |||

== Medical Management<br> == | |||

A study by Jonsson et al. (1994) found that 20% of patients had a protrusion of a cervical disc of grade 3 or grade 4 on MRI which correlated with neurological findings after a whiplash injury. [34 [LOE:3B]]<br> <br>Such patients might need to undergo anterior cervical discectomy [35 [LOE:4]].<br>After the discectomy, the surgeon might need to permanently stabilise the cervical spine. This can be achieved using artificial cervical disc or fusion of the cervical vertebrae. [84 [LOE :5]<br> | |||

<u>Medical interventions</u> | |||

*Steroid injections | |||

The cervical facet joint can be a source of pain in individuals with chronic WAD. Animal studies have demonstrated that cervical facet joint injury may be responsible for hypersensitivity and increased neuronal excitability.<br>Pain from the cervical facet joint can be medically managed using steroid injections to the specific zygopopsyal joints. Steroid injections can be used to treat acute and chronic WAD. However, the there are conflicting findings on the possible outcomes from such treatment [45 [LOE :1B]] [4 [LOE:1B]] [15 [LOE:1A]].<br>Pettersson et al. suggests that a high dose of methyl-prednisolone therapy given to the patient within 8h after injury minimises the chance of developing chronic WAD. It is not often used because of the practical difficulties of this treatment (8h limitation, 23-h infusion, need for hospitalisation, cost) [45 [LOE :1B]].<br> | |||

*Radiofrequency neurotomy | |||

The nociception input from the cervical facet joint can be modulated via radiofrequency neurotomy (RFN).<br>The radiofrequency neurotomy is a neuroablative procedure used to interrupt nociceptive pathways and uses heat generated by radio waves to target specific nerves (medial branch emitted by dorsal ramus) and temporarily interfere with their ability to transmit pain signals from the facet joints. The RNF can improve the pain, disability widespread hyperalgesia to pressure and thermal stimuli, nociceptive flexor reflex threshold, and brachial plexus provocation responses as well as increased neck range of motion one month and up to 3 months after the RFN. [55 [LOE :4]] A prospective study with chronic WAD patients who underwent CRFN treatment, showed an improvement in 70% of patients based on a number of parameters including Neck Disability Index and cervical range of motion [47 [LOE :3B]] [54 [LOE :1A]]<br> | |||

*Botulin toxin treatment | |||

Botulinum Toxin-A (BTX-A) decreases muscle spasm that contribute to both pain and dysfunction. Pain and range of motion with patients with chronic grade 2 WAD improves 2 to 4 weeks post treatment [27 [LOE: 1B]]. [85 [LOE: 1A]<br>The effect of the Botulinum toxin lasts nearly 8-12 weeks. Most patients treated with Botulinum toxin require repeated injections over many years. [44 [LOE :5]]<br>Other interventions are sterile water injections, saline injections, dextrose, lidocaine intra-articular injections and epidural blood patch therapy. However, it is not clear whether these treatments are actually beneficial. Further research is required to determine the efficacy and the role of invasive interventions in the treatment of chronic WAD [72 [LOE:1A]].<br> <br> | |||

<u>Surgical interventions</u><br> | |||

The following surgical interventions can be used to treat chronical WAD if the non-invasive treatments (including multimodal physical therapy) did not provide satisfactory results. [15 [LOE:1A]]<br> | |||

*Cervical discectomy and anterior cervical fusion | |||

Indications for surgery include severe and prolonged headache, neck and radicular pain if the symptoms identified during the clinical examination are in agreement with the radiographic findings. [1 [LOE :3B]]<br>During cervical discectomy, an incision is made in annulus fibroses and the nucleus pulposus is removed. Most of the disc is extracted. Anterior cervical fusion normally follows the cervical discectomy in order to stabilise the vertebrae. A bone graft is inserted where the discus used to be. The bones grow together to set the bony bridge between the vertebrae. The anterior part of the vertebras are stabilised by a metal plate that provides additional stability. The whole fusion process takes between 6 to 12 months, depending on the graft being used. [3 [LOE:2A]] This type of procedure reduced headache and neck pain, paraesthesia and radicular pain in some patients 4 years after the surgery [1 [LOE :3B]]. <br><br> | |||

== Physical Management<br> == | |||

<br> | Management approaches for patients with WAD are poorly researched. Very often these patients do not fit into treatment categories as defined for other cervical pain problems due to multiple factors, and even within the WAD group there are multiple variances which warrant individualised treatment approaches. [62 [LOE :3B]]<br> | ||

Whiplash-associated disorder is a debilitating and costly condition of at least 6-month duration. Although the majority of patients with whiplash show no physical signs [42 [LOE :1A]], studies have shown that as many as 50% of victims of whiplash injury (grade 1 or 2 WAD) will still be experiencing chronic neck pain and disability six months later [26 [LOE :2A]]. In most cases, symptoms are short lived. Only a substantial minority goes on to develop LWS (late whiplash syndrome), i.e. persistence of significant symptoms beyond 6 months after injury [36 [LOE:2C]]. Available data suggest that the combination of the injury with psychological factors such as coping style and explanatory style may lead to chronic WAD. [54 [LOE :1A]] | |||

=== Acute whiplash<br> === | |||

Treatment for acute whiplash can be delayed due to multiple social, economic, and psychological factors [82 [LOE:1A]] Psychological factors such as depression, anxiety, expectations for recovery, and high psychological distress have been identified as important prognostic factors for WAD patients. [42 [LOE :1A]]<br>Coping strategies such as diverting attention and increasing activity are related to positive outcomes[42 [LOE :1A]]. Another review with a high evidence level recommends that patients suffering from acute WAD “act as usual” and do early, controlled, physical activity within their tolerance level. [54 [LOE:1A]] [63 [LOE:1A]]<br>Education provided by physiotherapists or general practitioners is important in preventing of chronic whiplash, and must be part of the biopsychosocial approach for whiplash patients. The most important goals of the interventions are: | |||

#Reassuring the patient | |||

#Modulating maladaptive cognitions about WAD | |||

#Activating the patient [42 [LOE :1A]] | |||

The target of education is removing therapy barriers, enhancing therapy compliance and preventing and treating chronicity. [42 [LOE :1A]]<br> <br>There is strong evidence that to reduce pain, disability and improve mobility both verbal education and written advice are helpful. According to Meeus et al., in acute patients oral information is equally as efficient as an active exercise program. [42 [LOE :1A]]<br>In subacute or chronic patients, a programme integrating information, exercises and behavioural programmes, and a multidisciplinary programme, seem necessary. For more information on this refer to the section on chronic WAD.<br>In acute whiplash patients, a short oral education session is effective in reducing pain and enhancing mobility and recovery. Different types of education include [42 [LOE :1A]]: | |||

#'''Oral Education''': there is strong evidence for providing oral education concerning the whiplash mechanisms and emphasising physical activity and correct posture. It has better effect on pain, cervical mobility, and recovery, compared to rest and neck collars. Furthermore, studies show that oral education could be as effective as active physiotherapy and mobilisation. | |||

#'''Psycho – educational video''': A brief psycho-educational video shown at the patient's bedside seems to have a profound effect on subsequent pain and medical utilisation in acute whiplash patients, compared to the usual care. [42 [LOE :1A]] [70 [LOE :1A]] [30 [LOE :1A]] | |||

<br>According to the Whiplash book education and information given to the patient must contain the following information: | |||

*Reassurance that prognosis following a whiplash injury is good. | |||

*Encouragement to return to normal activities as soon as possible using exercises to facilitate recovery | |||

*Reassurance that pain is normal following a whiplash injury and that patients should use analgesia consistently to control this | |||

*Advice against using a soft collar [36 [LOE:2C]]. | |||

More studies are required to provide firm evidence for the type, duration, format, and efficacy of education in the different types of whiplash patients. [42 [LOE :1A]] [70 [LOE :1A]]<br>Future research should be founded on sound adult learning theory and learning skill acquisition [30 [LOE :1A]].<br> <br>Different types of exercise can be considered for WAD, including ROM exercises, McKenzie exercises, postural exercises, and strengthening and motor control exercises. It is not clear which type of exercise is more effective or if specific exercise is more effective than general activity or merely advice to remain active [63 [LOE:1A]]<br> <br>Active treatment which consists of early active mobilisation that is applied gently and over a small ROM, and which is repeated 10 times in each direction every waking hour seems to be as effective at reducing the pain after the whiplash injury as on ROM. This exercise can also be given as homework [51 [LOE :1B]]<br> <br>In a randomised study by A. Söderlund et al., where the aim was to compare two different home exercise programs in acute WAD, the result was that a home exercise programme, including training of neck and shoulder ROM, relaxation and general advice, seems to be sufficient treatment for acute WAD patients when used on a daily basis. [57 [LOE :1B]]<br> <br>Supported by several high and low quality studies, evidence-based therapy for acute WAD consists of early physical activity, mobilisation and education.<br>From this, we can conclude that there is strong evidence to suggest that exercise programs and active mobilisation significantly reduces pain in the short term and there is evidence that mobilisation may also improve ROM. [70 [LOE:1A]] [50 [LOE:1A]] [14 [LOE:1A]] [8 [LOE:1B]] [40 [LOE:1B]] [51 [LOE :1B]]<br> <br>Spinal manualtherapy is often used in the clinical management of neck pain. It is not easy to tease out the effects of manual therapy alone because most studies used it as part of a multimodal package of treatment.<br>Systematic reviews of the few trials that have assessed manual therapy techniques alone concluded that manualtherapy, such as passive mobilisation, applied to the cervical spine may provide some benefit in reducing pain, but that the included trials were of low quality. [63 [LOE:1A]]<br> <br>Patients with grades 1 and 2 2 WAD showed good results in a multimodal treatment program including exercises and group therapy, manual therapy, education and exercise. At their 6 months follow-up, 65% of subjects reported a complete return to work, 92% reported a partial or complete return to work, and 81% reported no medical or paramedical treatments over 6 months [77 [LOE:4]].<br>For the early management of WAD grades 1 and 2, general practitioner care includes advice to stay active and resumption of regular activities.<br>The synthesis of DA Sutton et al. suggests that patients receiving high-intensity health care tend to experience poorer outcomes than those who receive fewer treatments for WAD and NAD. [66 [LOE:1A]]<br> <br>Another interesting topic is the use of a collar. The use of a collar stands in contrast with what is indicated in most of the studies; activation, mobilisation and exercise. In a randomised study of Bonk et al. subjects were randomly assigned to a collar therapy group or to the exercise group. During a one week period participants had to record their average pain and disability in a diary, using the VAS scale. The results showed a significant difference between the groups, with positive effects on the prevalence of symptoms in the exercise therapy group compared to the collar group at six weeks. It is proven that early exercise therapy is superior to collar therapy in reducing pain intensity and disability for whiplash injury. Other studies also showed that exercise therapy gives a better pain relief than a soft collar. [70 [LOE:1A]] [52 [LOE:1B]] [51 [LOE :1B]]<br><br> | |||

=== Chronic Whiplash === | === Chronic Whiplash === | ||

There is a difference between a patient suffering from acute whiplash and a patient suffering from chronic whiplash. There is a suggestion that the injury in combination with psychological factors may lead to chronic WAD. [54 [LOE:1A]]<br> <br>A multidisciplinary therapy with cognitive, behavioural therapy and physical therapy, including neck exercises is effective in the management of WAD patients with chronic neck pain [32 [LOE:1B]] [54 [LOE:1A]] [71 [LOE:1A]] | |||

In patients with chronic WAD, negative thoughts are very important | When behavioural therapy is used in the therapy, it decreases the patient’s pain intensity in problematic daily activities. Therefore functional behavioural analyses can be used to adapt planning and treatment. [56 [LOE:4]]<br>There is evidence that exercise programs have a positive result in reducing pain in the short term. Exercise programmes are the most effective noninvasive treatment for patients with chronic WAD, although many questions remain regarding the relative effectiveness of various exercise regimens. There is also evidence suggesting that coordination exercises should be added to the treatment to reduce neck pain.<br>Multidisciplinary therapy gives positive results according to the reductions of neck pain and sick leave reported. [54 [LOE:1A]] [71 [LOE:1A]]<br>This is also the therapy recommended by the Dutch clinical guidelines for WAD. [73 [LOE:1A]]<br> <br>In patients with chronic WAD, negative thoughts are a very important factor. Self-efficacy, a measure of how well an individual believes he can perform a task or specific behaviour and emotional reaction in stressful situations, was the most important predictor of persistent disability in those patients. [9 [LOE:1B]]<br>Negative thoughts and pain behaviour can be influenced by specialists and physical therapists by educating patients with chronic WAD on the neurophysiology of pain. Improvement in pain behaviour resulted in improved neck disability and increased pain-free movement performance and pain thresholds according to a pilot study. [76 [LOE:3B]] <br>Michaleff et al. even found that simple advice is equally as effective as a more intense and comprehensive physiotherapy exercise programme. [43 [LOE:1B]]<br> <br>In a case report of Ferrantelli J.R.et al., the patient underwent a Clinical Biomechanics of Posture Rehabilitation in which he received mirror-image cervical spine adjustments, exercises and traction to reduce head protrusion and cervical kyphosis. The first ten visits included regional bilateral long-lever cervical spinal manipulation to temporarily decrease pain and increase ROM, and there after the structural rehabilitation care started. This treatment consisted in mirror-image drop table adjustments, mirror-image handheld instrument adjustments, mirror-image isometric exercise and mirror-image extension-compression traction for the reduction of the abnormal anterior translation posture of the head. After 5 months, the patient’s chronic WAD symptoms were improved. [24 [LOE:4]]<br> <br>As Michaleff et al. says in his article, we can conclude that an important health priority is the need to identify effective and affordable strategies to prevent and treat acute to chronic whiplash associated disorders. [43 [LOE:1B]]<br><br> | ||

<br> | === Summary<br> === | ||

< | <u</u>Below is a listing of the various therapy techniques and studies with key evidence.<br> | ||

<u>'''EVIDENCE CONCERNING IMMOBILIZATION'''</u><br> | <u>'''EVIDENCE CONCERNING IMMOBILIZATION'''</u><br> | ||

| Line 364: | Line 550: | ||

|} | |} | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

== Key Evidence == | == Key Evidence == | ||

| Line 376: | Line 558: | ||

[http://whiplashinfo.se/artiklar_debatt_forskning_asikter/redefining_whiplash.pdf "Whiplash associated disorders- redefining whiplash and its management" by the Quebec Task Force: a critical evaluation.] | [http://whiplashinfo.se/artiklar_debatt_forskning_asikter/redefining_whiplash.pdf "Whiplash associated disorders- redefining whiplash and its management" by the Quebec Task Force: a critical evaluation.] | ||

== Resources <br> == | == Resources <br> == | ||

[http://www.slsportstherapy.com/content/documents/PIER/SLST/Whiplash-PIER-SLST.pdf Evidence-based summary]<br> | |||

[[Manual_Therapy_and_Exercise_for_Neck_Pain:_Clinical_Treatment_Tool-kit|Manual Therapy and Exercise for Neck Pain: Clinical Treatment Tool-kit]] <br> | |||

<br> | |||

== Clinical Bottom Line<br> == | |||

Whiplash associated disorders (WAD) are a result of a previous whiplash injury and has a variety of characteristics and symptoms. This clinical presentation can be divided into different grades, reported by The Quebec Task Force. This classification is widely used and gives recommendations about the possible therapy. When a patient has a WAD several anatomical tissues can be affected, depending on the force and direction of the impact. Some people are more likely to develop WAD than others. To diagnose WAD radiographic images are not the norm, unless it concerns a WAD Grade III and IV. It’s more useful to make a clinical diagnosis based on the clinical presentation and anamnesis. Depending on severity of the WAD different medical/surgical interventions are needed. The most common interventions are steroid injections, radiofrequency neurotomy, botulin toxin treatment, cervical discectomy and cervical fusion. Although there are a lot of medical interventions, a WAD can also be treated in a conservative way. The therapy of an acute whiplash should consist of education, where it’s made clear by the therapist to stay active and ‘act as usual’, and early physical activity and mobilization. For the management of chronic whiplash there is strong evidence that a multidisciplinary therapy is effective. This therapy also has to consist of an exercise program.<br> | |||

<br> | |||

== Presentations == | == Presentations == | ||

| Line 402: | Line 594: | ||

== References == | == References == | ||

[[Category:Elbow|Elbow]] | |||

< | 1. Algers G. et al. Surgery for chronic symptoms after whiplash injury. Follow-up of 20 cases: Acta Orthop Scand. 1993 vol. 64, nr. 6 p. 654-6. [LOE: 3B]<br>2. ANGST F. et al. (2014). Multidimensional associative factors for improvement in pain, function, and working capacity after rehabilitation of whiplash associated disorder: a prognostic, prospective, outcome study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord., 15, 130. [LOE: 2B]<br>3. Anthony M. et al. Bone graft substitutes in anterior cervical discectomy and fusion: Eur Spine J: 2009 vol. 18, nr. 4, p. 449–464. [LOE: 2A]<br>4. Barnsley L. et al. “Lack of Effect of Intraarticular Corticosteroids for Chronic Pain in the Cervical Zygapophyseal Joints” N Engl J Med., vol. 330, p. 1047-1050, 1994 . [LOE: 1B]<br>5. Bekkering GE. et al., KNGF-richtlijn: whiplash. Nederlands tijdschrift voor fysiotherapie nummer 3/jaargang 11. [LOE 1A]<br>6. BINDER A., The diagnosis and treatment of nonspecific neck pain and whiplash, Eura Medicophys 2007, vol. 43, nr. 1, p. 79-89. [LOE: 5]<br>7. Binder A. Neck pain. Clin Evid (Online). 2008 Aug 4;2008. [LOE:1A]<br>8. Bonk AD. Et al. (2000). Prospective, randomised, controlled study of activity versus collar, and the natural history for whiplash injury, in Germany. World Congress on Whiplash-Associated Disorders in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, February 1999. J Musculoskel Pain 8: 123–132.[LOE:1B]<br>9. Bunketorp L et al. (2006). The perception of pain and pain related cognition in subacute whiplash-associated disorders: its influence on prolonged disability. Disabil Rehabil, 28(5): p.271–279 (2) [LOE: 1B]<br>10. Cassidy JD. et al. (2000). Effect of eliminating compensation for pain and suffering on the outcome of insurance claims for whiplash injury. N Engl J Med., 342(16), pp. 1179-86.[LOE: 3B] <br>11. Carstensen TB. et al. (2012). The influence of psychosocial factors on recovery following acute whiplash trauma. Dan Med J., 59(12).[LOE: 5]<br>12. Coleman T. (2014). Symptoms of whiplash neck injury, treatment for acute tinnitus, fatigue syndrome. Geraadpleegd op 26 april 2016 via http://www.tinnitusmiracle.com/Tinnitus-Miracle-Video.php?hopc2s=galus&tid=2016 [LOE 5]<br>13. CHIEN A. et al., Whiplash (grade II) and cervical radiculopathy share a similar sensory presentation: an investigation using quantative sensory testing, Clin J Pain 2008, vol. 24, nr. 7, p. 595-603. [LOE: 3B]<br>14. Conlin A. et al. (2005). Treatment of whiplash-associated disorders-part I: Non-invasive interventions. Pain Res Manag 10(1):21-32.[LOE: 1A]<br>15. Conlin A. et al. Treatment of whiplash-associated disorders-part II: Medical and surgical interventions: Pain Res Manag. 2005, vol. 10, nr. 1, p. 33-40. [LOE: 1A] <br>16. Crutebo S. et al. (2010). The course of symptoms for whiplash-associated disorders in Sweden: 6-month followup study. J. Rheumatol., 37(7), pp. 1527-33 [LOE 2B] <br>17. Delfini R. et al. (1999). Delayed post-traumatic cervical instability. Surg Neurol.,51 Pp.588-595. [LOE 2A ]<br>18. Drescher K. et al. Efficacy of postural and neck-stabilisation exercises for persons with acute whiplash-associated disorders: a systematic review. Physiother Can. 2008 Summer;60(3):215-23 [LOE:1A]<br>19. Eck JC. Et al. Whiplash: a review of a commonly misunderstood injury., Am J Med., 2001;110:651–6. [LOE 2A]<br>20. Elliott et al. (2009). Characterization of acute and chronic whiplash-associated disorders. Journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy, 39(5), pp. 312-323 [ LOE 5] <br>21. Erbulut DU. (2014). Biomechanics of neck injuries resulting from rear-end vehicle collisions. Turk. Neurosurg., 24(4), pp. 466-470 [LOE 2A] <br>22. EVANS RW. , Persistent post-traumatic headache, postconcussion syndrome, and whiplash injuries: the evidence for a non-traumatic basis with an historical review, Headache 2010, vol. 50, nr. 4, p. 716-724. [LOE: 4]<br>23. Fernandez Perez AM. et al. (2012). Muscle trigger points, pressure pain threshold, and cervical range of motion in patients with high level of disability related to acute whiplash injury, J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther.,42(7), pp. 634-641 [LOE 2B]<br>24. FERRANTELLI J.R. et al., Conservative Treatment of a patient With Previously Unresponsive Whiplash-Associated Disorders Using Clincal Biomechanics of Posture Rehabilitation Methods, J Manupulative Physiol Ther. 2005, vol. 28, nr. 3, p. 1-8. [LOE: 4]<br>25. Ferrari R. et al. (2005). A re-examination of the whiplash associated disorders (WAD) as a systemic illness. Ann Rheum Dis., 64, pp. 1337-1342 [LOE 2B]<br>26. Ferrari R. et al. Simple Educational Intervention to Improve the Recovery from Acute Whiplash: Results of a Randomised, Controlled Trial. Acad Emerg Med. 2005 Aug;12(8):699-706. [LOE:2A]<br>27. Freund BJ. Et al. « Treatment of whiplash associated neck pain with botulinum toxin-A: a pilot study » J Rheumatol., vol. 27, nr. 2, p. 481-4, 2000. [LOE: 1B] <br>28. Gargan MF. Et al. (1994).The rate of recovery following whiplash injury. Eur Spine J, 3, pp. 162 [LOE 2B]<br>29. Graziano D.L. et al. (2007). Positive Cervical Artery Testing in a Patient with Chronic Whiplash Syndrome: Clinical Decision-Making in the Presence of Diagnostic Uncertainty. J Man Manip Ther. 15 (3), pp. 45–63. [LOE: 3B]<br>30. Gross A. et al. Patient education for neck pain. COCHRANE DATABASE OF SYSTEMATIC REVIEWS. 2012;3 [LOE: 1A] <br>31. GUO LY et al., Three-dimensional characteristics of neck movements in subjects with mechanical neck disorder, J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil., 2012, vol. 25, nr. 1, p. 47-53. [LOE: 3B]<br>32. Hansen IR. et al. Neck exercises, physical and cognitive behavioural-graded activity as a treatment for adult whiplash patients with chronic neck pain: design of a randomised controlled trial. BMC musculoskelet disord. 2011; 12 [LOE: 1B]<br>33. HOLM L.W. (2008). The Burden and Determinants of Neck Pain in Whiplash-Associated Disorders After Traffic Collisions: Results of the Bone and Joint Decade 2000 –2010 Task Force on Neck Pain and Its Associated Disorders. Eur Spine J., 17(Suppl 1), pp. 52–59.[LOE: 1A]<br>34. Jonsson H. et al. “Findings and outcome in whiplash-type neck distortions.” Spine, vol. 19, p. 2733-43, 1994. [LOE: 3B]<br>35. Joslin CC. et al. « Long-term disability after neck injury. A comparative study. » J Bone Joint Surg Br., vol. 86, nr. 7, p. 1032-4, 2004. [LOE:4] <br>36. Lamb SE. Et al. MINT Study Team. Managing Injuries of the Neck Trial (MINT): design of a randomised controlled trial of treatments for whiplash associated disorders. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2007 Jan 26;8:7. [LOE:2C]<br>37. Lamb SE et al. Managing Injuries of the Neck Trial (MINT) Study Team. Emergency department treatments and physiotherapy for acute whiplash: a pragmatic, two-step, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2013 Feb 16;381(9866):546-56. [LOE:2A]<br>38. Loppolo F. et al. (2014). Epidemiology of Whiplash-Associated Disorders. Springer-Verlag Italia. [LOE: 1A] <br>39. McClune T. et al. (2002). Whiplash associated disorders: a review of the literature to guide patient information and advice. Emerg Med J,19, pp 499–506 [LOE: 2A] <br>40. McKinney LA. (1989). Early mobilisation and outcome in acute sprains of the neck. BMJ 299:1006–1008, [LOE :1B]<br>41. Mealy K. et al. Early mobilisation of acute whiplash injuries. Br Med J Clin Res Ed). 1986 Mar 8;292(6521):656-7. [LOE: 3A]<br>42. Meeus M. et al. Pain Physician. The efficacy of patient education in whiplash associated disorders: a systematic review. 2012 Sep-Oct;15(5):351-61. [LOE: 1A]<br>43. Michaleff ZA. et al., Comprehensive physiotherapy exercise programme or advice for chronic whiplash (PROMISE): a pragmatic randomised controlled trial, Lancet. 2014 Jul 12; 384(9938):133-41. [LOE 1B]<br>44. Nigam PK. and Nigam A.. BOTULINUM TOXIN. Indian J Dermatol: 2010. vol. 55, nr. 1, p. : 8–14. [LOE: 5] <br>45. Pettersson K. et al. “High-dose methylprednisolone prevents extensive sick leave after whiplash injury. A prospective, randomized, double-blind study” Spine, vol. 23, nr 9, p. 984-9, 1998. [LOE: 1B]<br>46. Phillips LA. Et al. (2010). Whiplash-associated disorders: who gets depressed? Who stays depressed?. Eur. Spine J., 19(6), pp. 945-956 [LOE 2B] <br>47. Prushansky T. et al. (2006). Cervical radiofrequency neurotomy in patients with chronic whiplash: a study of multiple outcome measures. J Neurosurg, 4(5): p.365–373. [LOE: 3B]<br>48. Radanov BP. Et al. (1992). Cognitive deficits in patients after soft tissue injury of the cervical spine. Spine, 17, pp. 127–131 [LOE 4]<br>49. Rodriquez A. et al. (2004). Whiplash: pathophysiology, diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis. Muscle Nerve, 29, pp. 768-81. [LOE: 4]<br>50. Rosenfeld M. et al.(2003). Active intervention in patients with whiplash-associated disorders improves long-term prognosis. A randomised controlled trial. Spine 28:2491–2498 [LOE: 1A] <br>51. Rosenfeld M. et al.(2000). Early intervention in whiplash-associated disorders: a comparison of two treatment protocols. Spine, vol. 25, nr. 14, p. 1782-7. [LOE: 1B]<br>52. Schnabel M.et al. (2004). Randomised, controlled outcome study of active mobilisation compared with collar therapy for whiplash injury. Emerg Med J 21:306-310[LOE: 1B] <br>53. SEE KS. “ Identifying upper limb disability in patients with persistent whiplash. “ Man Ther, vol. 20, nr. 3, p. 487-493, 2015. [LOE: 2C]<br>54. Seferiadis A. et al. (2004). A review of treatment interventions in whiplash-associated disorders, Eur Spine J, 13 : 387–397 [LOE:1A] <br>55. Smith AD. Et al. Cervical radiofrequency neurotomy reduces central hyperexcitability and improves neck movement in individuals with chronic whiplash: Pain Med. 2014 vol. 15, nr. 1, p. 128-41. [LOE: 4]<br>56. SÖDERLUND A. and LINDBERG P., An integrated physiotherapy/cognitive-behavioural approach to the analysis and treatment of chronic whiplash associated disorders, WAD, Disabil Rehabil 2001, vol. 23, nr. 10, p. 436-447. [LOE: 4]<br>57. Söderlund A. et al. (2000). Acute whiplash-associated disorders (WAD): the effects of early mobilization and prognostic factors in long-term symptomatology. Clin Rehabil. 4(5):457-67. [LOE: 1B] <br>58. Spitzer WO. et al. (1995). Scientific monograph of the Quebec Task Force on Whiplash-Associated Disorders: redefining "whiplash" and its management. Spine (Phila Pa 1976)., 20(8 Suppl), pp. 1-73. [LOE: 2C]<br>59. Stace R. and Gwilym S. « Whiplash associated disorder: a review of current pain concepts. » Bone & Joint 360, vol. 4, nr. 1. 2015. | [LOE: 2C]<br>60. STENNEBERG MS. et al. « Validation of a new questionnaire to assess the impact of Whiplash Associated Disorders: The Whiplash Activity and participation List (WAL) » Man Ther. vol. 20, nr. 1, p. 84-89, 2015. [LOE: 2C]<br>61. Sterling M. (2004). A proposed new classification system for whiplash associated disorders-implications for assessment and management. Man Ther., 9(2), pp. 60-70. [LOE 2A] <br>62. Sterling M. et al. (2006). Physical and psychological factors maintain long-term predictive capacity post-whiplash injury. Pain, 122, pp.102-108.[LOE 3B] <br>63. Sterling M. (2014). Physiotherapy management of whiplash-associated disorders (WAD). Journal of Physiotherapy, 60, pp. 5–12 [LOE:1A] <br>64. Sterling M. et al. (2004). Characterization of acute whiplash-associated disorders. Spine (Phila Pa 1976)., 29(2), pp. 182-188. [LOE: 2B] <br>65. Sterner Y. and Gerdle B. (2004). Acute and chronic whiplash disorders - a review. J Reabil Med 2004; 36: 193–210 [LOE 2C]<br>66. Stiell IG et al., The Canadian c-spine rule versus the NEXUS low-risk criteria in patients with trauma., N Engl J Med., 2003;349(26): 2510-2518. [LOE 2B]<br>67. Sturzenegger M. et al. (1994). Presenting symptoms and signs after whiplash injury: The influence of accident mechanisms. Neurol., 44, pp. 688–693 [LOE 2B]<br>68. Suissa et al. (2001). The relation between initial symptoms and signs and the prognosis of whiplash. Eur Spine J. 10, pp. 44-49. [LOE 2B]<br>69. Sutton DA. Et al.,Is multimodal care effective for the management of patients with whiplash-associated disorders or neck pain and associated disorders? A systematic review by the Ontario Protocol for Traffic Injury Management (OPTIMa) Collaboration. Spine J 2014;S1529-9430. [LOE 1A]<br>70. Teasell RW. Et al. A research synthesis of therapeutic interventions for whiplash-associated disorder (WAD): Part 2 – interventions for acute WAD. Pain Res Manage 2010;15(5):295-304.[LOE: 1A] <br>71. TEASELL RW. Et al., A research synthesis of therapeutic interventions for whiplash-associated disorder (WAD): part 4 - noninvasive interventions for chronic WAD, Pain Res Manag 2010, vol. 15, nr. 5, p. 313-322. [LOE: 1A]<br>72. Teasell RW. et al. A research synthesis of therapeutic interventions for whiplash-associated disorder (WAD): Part 5 – surgical and injection-based interventions for chronic WAD. Pain res manag: 2010. vol. 15, nr. 5, p. 323-334. [LOE: 1A]<br>73. van der Wees PJ. Et al . Multifaceted strategies may increase implementation of physiotherapy clinical guidelines: a systematic review. AustJPhysiother 2008,54(4):233-241.(1) [LOE: 1A] <br>74. Van Goethem J. et al. Spinal Imaging: Diagnostic Imaging of the Spine and Spinal Cord. p 258 [LOE: 2C]<br>75. Van Goethem J. et al., Whiplash injuries: is there a role for imaging?, Eur J Radiol., 1996;22:30–37. [LOE 3B]<br>76. Van Oosterwijck J. et al. (2011). Pain neurophysiology education improves cognitions, pain thresholds, and movement performance in people with chronic whiplash: A pilot study, Journal of rehabilitation research and development, (48) nr.1: p43-58 (3) [LOE: 3B]<br>77. Vendrig A. et al. (2000). Results of a multimodal treatment program for patients with chronic symptoms after a whiplash injury of the neck. Spine, 25 (2): p.238–244 (4) [LOE: 4]<br>78. Vernon H. The neck disability index: patient assessment and outcome monitoring in whiplash. Journal of Muskuloskeletal Pain 1996 vol. 4(4): 95-104.(2) [LOE:5]<br>79. VINCENT M.B., Headache and Neck, Curr Pain Headache Rep., 2011, vol. 15, nr. 4, p. 324-331 [LOE: 5]<br>80. Walton D.M. (2009). Risk Factors for Persistent Problems Following Whiplash Injury: Results of a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther, 39(5), pp. 334–350. [LOE: 1A] <br>81. Williamson E. et al. (2015). Risk factors for chronic disability in a cohort of patients with acute whiplash-associated disorders seeking physiotherapy treatment for persisting symptoms. Physiotherapy., 101(1), pp.34-43[LOE: 2B] <br>82. Yalda S. et al. (2008). Whiplash: diagnosis, treatment, and associated injuries, Curr. Rev. Muscoloskelet. Med., 1(1), pp. 65-68 [LOE 1A] <br>83. Clinical guidelines for best practice management of acute and chronic whiplash-associated disorders: Clinical resource guide, TRACsa: Trauma and Injury Recovery, South Australia, Adelaide 2008, p. 46-69. [LOE:1A]<br>84. Motor accidents authority (2001). Guidelines for Management of Whiplash-Associated Disorders: 8. [LOE: 5] <br>85. Baker JA and Pereira G, The efficacy of Botulinum Toxin A for spasticity and pain in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis using the Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation approach, Clin Rehabil 2013, vol. 27, nr. 12, p. 1084-1096. | ||

<br> | |||

Revision as of 10:48, 25 May 2016

Original Editor - Hannah Norton

Top Contributors - Kim Jackson, Rachael Lowe, Okebanama Nelson Onyebuchi, Lucinda hampton, Tarina van der Stockt, Admin, Hannah Norton, Van Horebeek Erika, Sigrid Bortels, Anouck Leo, WikiSysop, Steffen Kistmacher, Joshua Samuel, Ine Van de Weghe, Simisola Ajeyalemi, Rucha Gadgil, 127.0.0.1, Wanda van Niekerk, Jess Bell, Olajumoke Ogunleye and Robin Tacchetti

Search strategy

[edit | edit source]

Databases: Pubmed, Pedro, WebOfScience, emedicine, VUBmedical library, ScienceDirect, Google scholar

Keywords: ‘WAD range of motion’ and ‘WAD physical therapy’ and ‘prevalence WAD’ and ‘cause WAD’ and ‘prognostic factors WAD’ and ‘WAD diagnosis’ and ‘Whiplash injuries’ and ‘characterization WAD’

Definition/description

[edit | edit source]

Whiplash is an acceleration-deceleration mechanism of energy transfer to the neck. It may result from rear-end or side-impact motor vehicle collisions, but can also occur during diving or other or following other types of falls. The impact may result in bony or soft-tissue injuries (whiplash-injury), which in turn may lead to a variety of clinical manifestations called Whiplash-Associated Disorders (WAD). Spitzer WO et al (1995) [58 [LOE:2C]]

It is estimated that about 30% to 50% of patients who sustain a symptomatic whiplash injury are going to report chronic, and potentially more widespread symptoms, which may be classified as WAD. [59 [LOE:2C]]

WAD is a good example of a medical condition where there is often an apparent disconnect between the magnitude of injury and the magnitude of disability. [59 [LOE:2C]]

According to the Quebec Task Force of WAD there is a clinical grading of whiplash injuries. [74 [LOE:2C]] This will be explained in point 5. Characteristics/Clinical Presentation.

Clinically Relevant Anatomy

[edit | edit source]

Whiplash and whiplash-associated disorders (WAD) affect variable areas of the cervical spine, depending on the force and direction of impact as well as many other factors. [12 [LOE:5]]

Chronic WAD implicates neuromusculoskeletal lesions, including dysfunctions of [29 [LOE:3B]] [35 [LOE:4] :

- the cervical zygapophyseal joints

- Atlanto-axial joint

- Atlanto-occipital joint

- intervertebral disc

- cartilaginous endplates

- muscles

- ligaments:

- Alar ligament

- Anterior atlanto-axial ligament

- Anterior atlanto-occipital ligament

- Apical ligament

- Anterior longitudinal ligament

- Transverse ligament of the atlas

- vertebrae

- nervous systems structures:

- nerve roots

- spinal cord

- brain

- sympathetic nervous system

- Temporomandibular joint

- Acromioclavicular joint

- the peripheral vestibular system

- the cervical arteries

- internal carotid

- vertebral artery

Anatomic causes of pain can be any of these tissues, with the strain injury resulting in secondary edema, hemorrhage, and inflammation.

Epidemiology/etiology

[edit | edit source]

The risk that patients develop WAD after an accident with acceleration-deceleration mechanism of energy transfer of the neck depends on a variety of factors.

In a study by Holm et al, it was demonstrated that one of the key factors for developing WAD is the severity of the impact. However, it is difficult to obtain objective evidence to confirm this. [33 [LOE:1A]]

According to the study by D. Obelieniene et al., there is evidence that neck pain present before the accident is a risk factor for acute neck pain after collision. [38 [LOE:1A]]

In addition, some people are more likely to develop WAD than others., In particular, women seem to be slightly more at risk of developing WAD. Age is also important; younger people (18-23) are more likely to file insurance claims and/or are at greater risk of being treated for WAD. [10 [LOE: 3B]] [39 [LOE:2A]]

There are several prognostic factors that determine the evolution of WAD and the likelihood that it will evolve into chronic pain.

- According to Carstensen et al., the following factors: pre-collision self-reported unspecified pain, high psychological distress, female gender and low educational level predicted future self-reported neck pain. He also demonstrated that self-reported characteristics before the collision are important for recovery. [11 [LOE: 5]]

- In another study, prognostic factors were: no postsecondary education, female gender, history of previous neck pain, baseline neck pain intensity greater than 55/100, presence of neck pain at baseline, presence of headache at baseline, catastrophising, WAD grade 2 or 3, and no seat belt in use at the time of collision. [80 [LOE:1A]]

- If the patient was out of work before the accident, sick-listed, or had social assistance, this can also be associated with a negative evolution following whiplash trauma. Illness notification before the accident can also be associated with neck pain in the future. [11 [LOE : 5]]

- Baseline disability had the strongest association with chronic disability, but psychological and behavioural factors were also important. [81 [LOE :2B]]

JD Cassidy and Scholton-Peeters demonstrated in their studies that 14 to 42 % of the whiplash patients are at risk of developing chronic complaints (longer than 6 months) and that 10 % of those have constant severe pain. The number of people worldwide who suffer from chronic pain is between 2 and 58 %, but lies mainly between 20 and 40%. [38 [LOE :1A]]

If patient still have symptoms 3 months after the accident they are likely to remain symptomatic for at least two years, and possibly for much longer. [39 [LOE:2A]]

Based on several studies, we can conclude that the prevalence of WAD depends on the country or the part of the world. For example, the prevalence per 100,000 inhabitants is of 70 in Quebec, 106 in Australia and 188–325 in the Netherlands.

But according to the study of Versteegen, in which he studied patients with neck pain following a car accident in the last ten years, the prevalence per 100,000 inhabitants increased significantly from to 3.4 in 1974 to 40.2 in 1994. A study by Richter also shows an increase in prevalence of 20% between 1985 and 1997. The increase is due in part to a higher number of cars on the roads, which in turn can lead to more accidents. However, this increase in prevalence is also due to the fact that there is a greater public awareness of WAD and therefore those affected are more likely to consult their doctor and therefore the number of patients seeking healthcare for whiplash is on the rise. [33 [LOE:1A]] [38 [LOE:1A]]

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Whiplash-associated disorders, is a complex condition with varied disturbances in motor, sensorimotor, and sensory functions and psychological distress. [20 [LOE:5][21 [LOE:2A]] The most common symptoms are sub-occipital headache and/or neck pain that is constant or motion-induced. [25 [LOE:2B]] There may be up to 48 hrs delay of symptom onset from the initial injury.[17 [LOE:2A]]

- Motor dysfunction:

- One of the most common clinical characteristics is a restricted range of motion of the cervical spine. This finding may reflect underlying disturbances in motor function due to the initial peripheral nociceptive input caused by injured anatomical cervical structures. Further research of such potential mechanisms in WAD is necessary. [20 [LOE:5]] [12]

- Another characteristic is altered patterns of muscle recruitment in both the cervical spine and shoulder girdle regions. This is clearly shown to be a feature of chronic WAD. [20 [LOE:5]] [61 [LOE :2A]] [62 [LOE :2A]] [68 [LOE :2B]]

- Mechanical cervical spine instability [17 [LOE:2A]]

- Sensorimotor dysfunction

- Loss of balance

- Disturbed neck influenced eye movement control [17 [LOE:2A]]

- Sensorimotor dysfunction is greater in patients who also report dizziness due to the neck pain. [20 [LOE:5]] [74 [LOE :2C]] [67 [LOE :2B]

- Sensory dysfunction: sensory hypersensitivity to a variety of stimuli

- Psychological distress

- Posttraumatic stress [20 [LOE:5]]

- Concentration and memory problems [74 [LOE :2C]] [67 [LOE :2B]

- Anxiety [67 [LOE :2B]]

- Depression [67 [LOE :2B] is common in WAD patients. There are different types we can distinguish:

■ Initial depression: this can be associated with greater neck and low back pain severity, numbness/tingling in arms/hands, vision problems, dizziness, fracture, [46 [LOE:2B]]

■ Persistent depression: this can be associated with older age, greater initial neck and low back pain, post-crash dizziness, anxiety, numbness/tingling, vision and hearing problems [46 [LOE:2B]]

- Degeneration cervical muscles

- Neck stiffness [74 [LOE :2C]] [67 [LOE :2B]

- Fatty infiltrate may be present in the deep muscles in the suboccipital region and the multifidi may account for some of the functional impairments such as: Proprioceptive deficits, Balance loss, Disturbed motor control of the neck [20 [LOE:5]] [25 [LOE:2B]] [61 [LOE :2A]] [62 [LOE :2A]] [68 [LOE :2B]] [74 [LOE :2C]] [67 [LOE :2B]

The following symptoms may also occur [67 [LOE :2B] [17 [LOE:2A]]:

- Tinnitus

- Malaise

- Disequilibrium/Diziness

- Thoracic, temporomandibular, facial, and limb pain

It is important to carry out thorough spinal and neurological examinations in patients with WAD to screen for delayed onset of the cervical spine instability or myelopathy. [17 [LOE:2A]] see point 9 examination.

Whiplash can be an acute or chronic disorder. In acute whiplash, symptoms last no more than 2-3 months, while in chronic whiplash symptoms last longer than three months. Patients with acute WAD experience widespread pressure hypersensitivity and reduced cervical mobility. [23 [LOE :2B]] Various studies indicate that there can be a spontaneous recovery within 2-3 months [28 [LOE:2B]]. According to the Quebec Task Force of WAD (QTF-WAD), 85% of the patients recover within 6 months.[5 [LOE:1A]]

In addition, according to a follow-up study by Crutebo et al. (2010), some symptoms were already transient at baseline and symptoms such as neck pain, reduced cervical range of motion, headache, and low back pain, decreased further over the 6 months period. They also investigated the prevalence of depression and found that at baseline this was around 5% in both women and men, whereas posttraumatic stress and anxiety were more common in women (19.7% and 11.7%, respectively) compared to men (13.2% and 8.6%). The majority of all reported associated symptoms were mild at both baseline and during follow-up. [16 [LOE:2B]]

According to the QTF-WAD there is a clinical grading of whiplash injuries. [74 [LOE:2C]]

QTFC (Quebec Task Force Classification)

[edit | edit source]

The Quebec Task Force was a task force sponsored by a public insurer in Canada. This Task Force developed recommendations regarding the classification and treatment of WAD, which were used to develop a guide for managing whiplash in 1995.[58 [LOE :2C]] An updated report was published in 2001. Each of the QTFC grades corresponds to a specific treatment recommendation. [61 [LOE:2A]]

| QTFC Grade |

Clinical presentation |

| 0 |

No complaint about neck pain No physical signs |

| I |

Nec complaints of pain, stiffness or tenderness only No physical signs |

| II |

Neck complaint Musculoskeletal signs including

|

| III |

Neck complaint Musculosceletal signs Neurological signs including:

|

| IV |

Neck complaint and fracture or dislocation |

MQTFC (Modified Quebec Task Force Classification) [61 [LOE:2A]]

|

Proposed classification grade |

Physical and psychological impairments present |

| WAD 0 |

No complaints about neck pain No physical signs |

| WAD I |

No complaints of pain, stiffness or tenderness only No physical signs |

| WAD IIA |

Neck complaint Motor impairment

Sensory Impairment

|

| WAD IIB |

Neck complaint Motor impairment

Sensory Impairment

Psychological impairment

|

| WAD IIC |

Neck complaint

Motor impairment

Sensory Impairment

Psychological impairment

|

| WAD III |

Neck complaint Motor impairment

Sensory Impairment

Neurological signs of conduction loss including:

Psychological impairment

|

| WAD IV |

Fracture or dislocation |

In addition, a classification based on subjective complaints and formal testing of self-estimated cognitive impairment, divided attention, and speed of information processing was suggested by Radanov and co-workers [48 [LOE :4]] :

- Lower cervical spine syndrome (LCS) accompanied by cervical and cervicobrachial pain.

- Cervicoencephalic syndrome (CES) characterized by headache, fatigue, dizziness, poor concentration, disturbed accommodation, and impaired adaptation to light intensity.

In comparison with the QTF classification, this system of classification incorporates

neuropsychological symptoms. [65 [LOE :2C]

Differential Diagnosis

[edit | edit source]

Soft tissue lesions:

- Cervical radiculopathy [13 [LOE :3B]]

- Cervical myelopathy [6 [LOE :5]]

- Vascular abnormality of cervical structures

Fibromyalgia and psychogenic causes: [6 [LOE :5]]

- Psychogenic pain disorder

- Facticious disorder

- Malingering [22 [LOE:4]]

Mechanical lesions:

- Cervical herniated disk [6 [LOE :5]]

- Mechanical Neck Disorder [31 [LOE:3B]]

Inflammatory:

- Inflammatory rheumatologic disease [6 [LOE :5]]

- Polymyalgia Rheumatica [6 [LOE :5]]

Metabolic: [6 [LOE :5]]

- Osteoporosis

- Cervical osteoarthritis

Infective:

- Infection or osteomyelitis [6 [LOE :5]]

Malignancy:

- Tumor or malignancy of cervical spine [6 [LOE :5]]

Adjacent pathology:

- Shoulder or acromioclavicular disease [6 [LOE :5]]

Other:

- Cervicogenic Headache [79 [LOE :5]]

- Referred pain from cardiothoracic structures

- Traumatic Brain Injury [22 [LOE :4]]

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

Clinical diagnosis

The diagnosis of WAD remains clinical and the mechanism of the injury must be elicited. [49 [LOE:4]] Based on the clinical presentation of the patient, WAD can be diagnosed. [61 [LOE:2A]] According to Rondriguez et al. (2004), there are no specific neuropsychological tests that can diagnose WAD. [49 [LOE:4]] However, there are several psychological symptoms, as described above in section 5. Characteristics/Clinical Presentation, that are associated with WAD. In addition, a whiplash profile has been developed with high scores on subscales of somatisation, depression and obsessive compulsive behaviour in patients with WAD. [10 [LOE:3B]]

Radiographic diagnosis

According to Yalda et al (2008), the injury is most often not identified radiologically in the acute phase [82 [LOE:1A]] . The most common radiographic findings are [19 [LOE:2A]]:

- preexisting degenerative disease

- slight loss of the normal lordotic curve of the cervical spine

- kyphotic angle at the time of injury → due to hypermobility and secondary to muscle spasm

MRI is not indicated at the time of initial presentation because of the high false positive results. [75 [LOE:3B]]

CT and MRI are generally used by patients with suspected spinal cord or disc injury, fracture or ligamentous injury. They may also be indicated in patients with long term persistent arm pain, neurological deficits, or clinical signs of nerve root compression [75 [LOE :3B]]

X-ray should be routinely used for the patients with WAD grade III and IV. If the X-ray gives positive results for fracture or dislocation, the patient should be immediately referred to an emergency department or to a specialist surgeon. [35 [LOE :4]]

Canadian C-Spine Rule (CCR) is an algorithm to determine the necessity for cervical spine radiography in alert and stable patients with trauma and cervical spine injury. [66 [LOE:2B]]

Outcome measures

[edit | edit source]

Neck Disability Index [5 [LOE :1A]] [78 [LOE :5]] [83 [LOE :1A]]

Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) [5 [LOE :1A]] [83 [LOE :1A]]

The Whiplash Activity a participation List (WAL) [60 [LOE :2C]]

Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand (DASH) in persistent Whiplash [53 [LOE:2C]]

SF-36 [2 [LOE :2B]], [83 [LOE :1A]]

Functional Rating Index [83 [LOE :1A]]

The Self-Efficacy Scale [83 [LOE :1A]]

The Coping Strategies Questionnaire [83 [LOE :1A]]

Patient-Specific Functional Scale [83 [LOE :1A]]

Core Whiplash Outcome Measure [83 [LOE :1A]]

The Kessler Psychological Distress Scale [83 [LOE :1A]]

The Impact of Event Scale [83 [LOE :1A]]

Examination

[edit | edit source]

Before examination, it is crucial to obtain anamnesis. History taking is important during all visits for the treatment of WAD patients, no matter which grade it is.

The history should include information about:

- date of birth, gender, occupation, number of dependants, marital status

- prior history of neck problems (including previous whiplash)

- prior history of physiological disturbances

- prior history of long-term problems (injury and illness)

- current psychosocial problems (family, job-related, financial)

- symptoms (location + time of onset)

- circumstances of injury (sport, motor vehicle;..), mechanism of injury, position of person when accident occurred, type of vehicle

- results of an assessment using tools to measure general psychological state and pain:

- General Health Questionnaire (CHQ)

- Visual Analogue pain Scale

- Neck Disability index

[84 [LOE :5]]

Physical examination is required to identify signs and symptoms. The examination procedure for patients with WAD is similar to the examination of the cervical spine. WAD can be divided into 4 grades according to the QTF-WAD. The findings of the examination will allow the grade to be determined.[63 [LOE:1A]]

The physical examination should begin with an inspection and palpation. During palpation, stiffness and tenderness of the muscles may be observed. These physical symptoms are present in grade 1, 2 and 3. Trigger points may also be observed in grade 2 and 3 WAD. The number of active trigger points may be related to higher neck pain intensity, the number of days since the accident, higher pressure pain hypersensitivity over the cervical spine, and reduced active cervical range of motion.

[23 [LOE:2B]]

The next step in the examination is ROM testing. In grade 1 WAD, there are no physical signs, so there will be no decreased ROM. In grades 2 and 3, a decreased ROM can be identified by testing the neck flexion, extension, rotation and 3D movements.

[63 [LOE:1A]] [23 [LOE:2B]]

To distinguish grade 3 from grade 2, neurological examination is needed. Patients with grade 3 have symptoms of hypersensitivity to a variety of stimuli. These can be subjectively reported by patients, and may include allodynia, high irritability of pain, cold sensitivity, and poor sleep due to pain.

Objectively, the results of the neurological examination are hyporeflection, decreased muscles force and sensory deficits in dermatome and myotome. These responses may occur independently of psychological distress. Other physical tests for hypersensitivity include pressure algometers, pain with the application of ice, or increased bilateral responses to the brachial plexus provocation test.

It is important to know that these neurological symptoms do not necessarily indicate peripheral nerve compression and may be a reflection of altered central nociceptive processes.

[63 [LOE:1A]]

These findings may be important for the differential diagnosis of acute whiplash injury. A poorer outcome is generally predicted in patients with higher initial pain and disability as well as hypersensitivty (e.g. cold hyperalgesia).

[63 [LOE:1A]] [64 [LOE :2B]]

To identify grade 4 WAD, which is a fracture or dislocation, medical imaging is needed. A simple test for including or excluding a fracture is to smite with the ulnar side of the fist on the spine. If there is a severe pain, one can speak of a fracture.

“In recent years, there has also been extensive research undertaken demonstrating movement, muscle, and motor control changes in the neck and shoulder girdles of patients with neck pain, including WAD. Study findings include inferior performance on tests of motor control involving the cervical flexor, extensor and scapular muscle groups when compared to asymptomatic control participants; changes in muscle morphology of the cervical flexor and extensor muscles; loss of strength and endurance of cervical and scapular muscle groups; and sensorimotor changes manifested by increased joint re-positioning errors, poor kinaesthetic awareness, altered eye movement control, and loss of balance. Detailed information on the clinical assessment of cervical motor function is available elsewhere. The rationale for the evaluation of such features is to plan an individualised exercise program for each patient based on the assessment findings.” M. Sterling (2014). Physiotherapy management of whiplash-associated disorders (WAD). [63 [LOE:1A]]

Cervical zygapophysial is in 50% of the WAD patients a symptom-giving structure. The cervical zygapophysial joint pain must therefore also be examined. [54 [LOE : 1A]]

Medical Management

[edit | edit source]

A study by Jonsson et al. (1994) found that 20% of patients had a protrusion of a cervical disc of grade 3 or grade 4 on MRI which correlated with neurological findings after a whiplash injury. [34 [LOE:3B]]

Such patients might need to undergo anterior cervical discectomy [35 [LOE:4]].

After the discectomy, the surgeon might need to permanently stabilise the cervical spine. This can be achieved using artificial cervical disc or fusion of the cervical vertebrae. [84 [LOE :5]

Medical interventions

- Steroid injections