Self-management Techniques to Enhance Physical Activity

Original Editor - - Justin Louie, Stuart Maytham, Dawn Williams, Paul Reen, Janelle Eisler Carr, Ciara Wright as part of the QMU Current and Emerging Roles in Physiotherapy Practice Project

Top Contributors - Justin Louie, Ciara Wright, Stuart Maytham, Kim Jackson, Paul Reen, Evan Thomas, 127.0.0.1, Admin, Scott Buxton and Rucha Gadgil </div>

Introduction[edit | edit source]

The following wiki is designed for registered practitioners and Physiotherapy students, with an interest in continual professional development, specifically with regards to the emerging role of the Physiotherapist with the increasing demands of a changing world.

The purpose of this wiki is to critically evaluate the current practice of Physiotherapy within the healthcare system with regards to the treatment of physical inactivity related Physiotherapy conditions. The wiki will acknowledge the increasing demands being placed on this area of practice and to help develop the understanding of the reader with respect to the potential solutions, with a focus on technology and health related behaviour change, to such increasing demands.

The cost of physical inactivity is placing a significant burden on the health care system. The Department of Health are encouraging the use of “self-management” techniques to promote long-term behaviour change with the aim to reduce cost. The goal is that people will feel “empowered” and “independent,” thus requiring less involvement with the health care service.

Physiotherapists are considered to be in an ideal position to utilise ‘teachable moments’ to encourage such self-management and overall health behaviour change. It is becoming more and more prevalent for Physiotherapists to have a good understanding of health related behaviour change and human behaviour in general. In order to move closer towards optimal patient-centred care, it is important that the consultation experience follows less of a policing approach but rather a more collaborative approach to promoting greater autonomy and empowerment for that individual patient into their future health related lifestyle. Such an approach may incorporate the growing market of quantified self-technologies and online health-related behaviour change tools.

Learning Outcomes[edit | edit source]

This resource will enable the user to:

- Critically evaluate and synthesise the key issues regarding the physical inactivity epidemic

- Identify and justify the knowledge, skills and behaviours required by a health coach in a physiotherapy setting

- Critically evaluate the use and feasibility of current and emerging technology to enable self management and health behavior change

- Discuss the emerging online tools ultilising more intensive theory-based interventions that incorporate multiple behaviour change techniques which may assist the Physiotherapist in their emerging role as a health coach.

Physical Inactivity[edit | edit source]

The World Health Organization (WHO) has identified “physical inactivity” as a global epidemic, with the region of the Americas having the highest prevalence of inactivity followed by the Eastern Mediterranean Region [1]. The cost of physical inactivity on the health care system is staggering. In the United Kingdom, the cost is estimated to be approximately £8.2 billion [2], whilst in Canada, the cost is approximately $6.8 billion (£3.76 billion) per year [3]. The United States of America spends more than 75% of the $2 trillion (£1.3 trillion) annual health care budget on physical inactivity related hospitalizations. [4].

|

|

One of the reasons for the high health care costs is the link between physical inactivity and several Non-Communicable Diseases (NCDs), such as cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), chronic respiratory diseases, cancer, and type two diabetes [6]. Physical inactivity is the fourth leading risk factor for global mortality, contributing to approximately 3.2 million deaths annually worldwide [7]. More than 50 years of statistical research confirms the relationship between physical activity and mortality (Pate et al, 1996), with reports suggesting that at least 80% of premature CVD and 40% of cancer deaths could have been prevented through regular physical activity [8].

For more information regarding mortality figures and the economic costs of physical inactivity, please visit the following links:

According to the WHO, there are several reasons for the worldwide physical inactivity epidemic in the regions of the Americas, including increased workplace and leisure-time sedentary behaviour. The increased sedentary lifestyle has been shown to predispose individuals to pain, disabling conditions, and musculoskeletal complaints. In the workplace, this may lead to injury, varying degrees of disability, absenteeism, reduced overall job performance, or other undesirable outcomes (Pronk & Kottke, 2009). These consequences of physical inactivity may contribute to absence due to sickness in the UK, which accounts for 3–4% of average working time and costs employers £9 billion each year and a further £20 billion to the UK economy (Chartered Institute of Personal Development, 2010). Also, the increase in urbanization has led to several environmental factors that discourage physical activity. These factors include increased traffic, increased pollution, and decreased access to parks and recreation facilities [9].

In order to combat this growing epidemic at a Global level, the WHO has developed the Global Recommendations on Physical Activity for Health guidelines. The Global Recommendations on Physical Activity for Health guidelines help educate people regarding the minimum amount of physical activity required to receive the benefit of a decreased risk of NCD [10] . There are three age categories, which are grouped according to the relevant scientific evidence regarding the prevention of NCD through physical activity [11] . The age groups are as follows: 5–17 years old, 18–64 years old, and 65 years old and above.

Several countries have adapted the Global Recommendations on Physical Activity for Health guidelines.

The Canadian Physical Activity Guidelines[13]

The United Kingdom Physical Activity Guidelines [14]

The United States of America Physical Activity Guidelines[15]

These physical activity guidelines can assist physiotherapists in their treatment of NCD conditions related to physical inactivity through education and promotion of physical activity self-management. It appears that traditional treatment strategies, such as diet, exercise, pharmacology, and behavioural therapy, are not consistently effective [16]. The Department of Health (2012)[17] are encouraging the use of “self-management” techniques to promote long-term behaviour change with the aim to reduce cost. The goal is that people will feel “empowered” and “independent,” thus requiring less involvement with the health care service.

Self-Management[edit | edit source]

Self-management is a model of care in which patients are encouraged to use strategies and learn skills to manage their own health needs [18]. Patients are active participants and take responsibility for their own health care behaviours, a notion that is lost in the medical model and passive therapies [19]. Recently, the WHO defined self- management as:

“the ability of individuals, families and communities to promote health, prevent disease, and maintain health…..to cope with illness and disability with or without the support of a health-care provider.” (2013)

The Scottish Government have dedicated £6 million over the past three years to the Long Term Conditions Alliance Scotland in their promotion of self-management. The document “Gaun Yersel” was developed in alliance with patients and outlines the responsibilities and commitments of the government in combination with their 2020 Vision whereby individuals and communities aim to achieve social change.

Swan 2012 highlights the paradigm shift in health care from the concept that the patient’s health is the responsibility of the health care professional to ‘My health is my responsibility, and I have the tools to manage it’ [20]. The NHS must continue to make the transition from a ‘sickness’ service to a ‘well-being’ service.

Lorig et al (2003)[21]. explain that “wellness” from self-management requires attention in three key domains: the medical, behavioural, and emotional elements of a person’s life. They recognise that physiotherapists do not have extensive training in each domain, but they stress that physiotherapists’ expertise in exercise therapy, pain management, and healthy lifestyles promotion enables the profession to play a key role in supported self-management.

Approaches[edit | edit source]

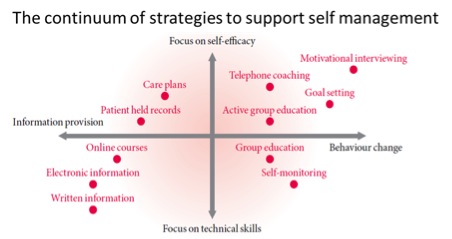

According to Phillips (2012) [22], a person needs to learn a range of skills to manage the biological, mental, emotional, and social impacts of their condition, including the effects of physical inactivity on health. This is termed the “biopsychosocial approach.” The following diagram depicts the range of strategies available to support the use of self-management:

|

Figure 1: The Health Foundation Evidence: Helping People Help Themselves, May 2011[23] |

Once a person has accepted that he or she has a lifestyle problem, a key element of self-management is the motivation to change behaviour. It is important to note that, if people are in denial about their inactivity levels, it will have a detrimental impact on their engagement with self-management treatment options [24].

The supported self-management approach is a collaboration between the physiotherapist and the individual in which the physiotherapist assists the person to make educated and informed decisions about their own goals and expectations for the future [25].

Goal Setting[edit | edit source]

There is much evidence available for the use of goal setting when attempting to change behaviours. One popular model of goal setting is SMART (link below to be inserted). Harding (2000)[26] suggests that patients should be encouraged, in conjunction with their therapist, to set individual and personalised goals. It is important to set targets at a manageable baseline to achieve something previously feared, which can then be recognised as an achievement.

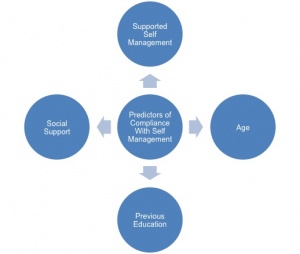

Predictors of Self Management Compliance[edit | edit source]

Concerns have been raised over the effectiveness of self-management and its ability to reduce pain and disability, or increase inactivity.

Crowe (2010)[28] echoes the point that, despite the current emphasis on self-management, there is minimal evidence to suggest which strategies are actually affective. It has been argued that long-term behavioural change is difficult to sustain without the input of a health care professional [29]. Oliveira discovered that many studies did not conform to a self-management definition, and there are varying approaches being used to promote self-management by health care professionals. The Chartered Society of Physiotherapy recently estimated that 50% of patients suffering a chronic condition ignore professional healthcare advice (2014); therefore, it is important to consider the patient’s expectations of self-management and the support they receive from their health care professional (HCP) [30]. Undoubtedly, self-management will be more effective with some patients than others. It is important to recognise that further research is required to determine which aspects of self-management are beneficial or non-beneficial, as well as how HCPs should encourage and promote its use to best effect.

A recent study (Kawi, 2014)[31] concluded that self-management may be effective for certain patient groups only, suggesting that indicators for compliance need to be established to recognise potential responders. The main predictors of compliance with self-management were:

- Age (generally, the younger the patient the higher the participation in self-management)

- Supported self-management (SSM) (the greater the amount of SSM available the higher the level of continued SM)*Previous education

- Better overall health

- Support received from family and friends increases compliance and motivation.

A key component for the success of self-management appears to be the level of support a patient receives from an appropriate HCP, such as a physiotherapist. The Cooper et al (2009)[32] paper identified that patients want direct access to their physiotherapist for follow-up advice and reassurance. This could take the form of a review visit, telephone call, or even an email. SSM is a vital component that cannot be ignored in the quest for cost reduction. Further research is required to better understand this relatively new approach to patient management. The core components of SSM need to be established, and support into the mental well-being of a patient is essential when delivering a biopsychosocial approach to SSM.

The Internet is increasingly being used to provide interventions, information, and guidance on health-related behaviour change. A recent survey reported that of the 74% of American adults who use the Internet, 80% have used it to find health information. Social networks in health and other types of social media provide people with new opportunities to share health information easily. With the prediction that 3 out of 4 mobile phone users in the UK will own a smartphone by 2016, it is important to recognise that the use of smartphone apps in conjunction with physiotherapy support may be used as a self-management tool to promote and enhance behaviour change.

What is Behaviour?[edit | edit source]

It is the response of the system or organism to various stimuli or inputs, whether..

Why is the General Population so Inactive?[edit | edit source]

Social

Cultural

Physiological

Learning Behaviours[edit | edit source]

Learning is the act of acquiring new, or modifying and reinforcing, existing knowledge, behaviours, skills, values, or preferences and may involve synthesizing different types of information.

- Non-associative learning refers to a relatively permanent change in the strength of response to a single stimulus due to repeated exposure to that stimulus.

- Habituation is a form of learning in which an organism decreases or ceases to respond to a stimulus after repeated presentations. E.g. feeling nervous/excited when you begin exercising but after a while you are unfazed by going.

- Sensitisation is an example of non-associative learning in which the progressive amplification of a response follows repeated administrations of a stimulus. E.g. increased sensitivity due to a history of chronic pain when attempting to exercise.

- Associative learning is the process by which an association between two stimuli or a behaviour and a stimulus is learned.

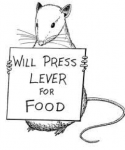

- Operant conditioning

- Classical conditioning

Habits[edit | edit source]

A habit is a routine of behaviour that is repeated regularly and tends to occur unconsciously.

The process by which new behaviours become automatic is habit formation. Old habits are hard to break and new habits are hard to form because the behavioural patterns we repeat are imprinted in our neural pathways, but it is possible to form new habits through repetition.

Health Behaviour Change[edit | edit source]

Actions to bring about behaviour change may be delivered at individual, household, community or population levels using a variety of means or techniques.

Significant events or transition points in people's lives present an important opportunity for intervening at some or all of the levels, because it is then that people often review their own behaviour and contact services.

The health promoting health service approach has developed the concept that ‘Every healthcare contact is a health improvement opportunity’. This is reinforced in the National Delivery Plan for the Allied Health Professions [AHPs] in Scotland, 2012-2015. However it could strongly be argued that Physiotherapists don’t have the adequate resources or training to tackle health behaviour change effectively [40].

Theories and Models[edit | edit source]

Behavioural change theories are attempts to explain why behaviours change. These theories cite environmental, personal, and behavioural characteristics as the major factors in behavioural determination.

Each behavioural change theory or model focuses on different factors in attempting to explain behavioural change.

- Theory of reasoned action

- Social cognition theory

- Theory of planned behaviour

[43].

[43].

- Transtheoretical model

- Health action process approach

- B=MAT Model

Self-Efficacy[edit | edit source]

Self-efficacy is an important factor in all the theories outlined above and is defined by Bandura as the extent or strength of one's belief in one's own ability to complete tasks and reach goals i.e. the more that we believe that we can achieve a goal the more likely we will be to do so

Self-efficacy affects every area of human endeavour. By determining the beliefs a person holds regarding his or her power to affect situations, it strongly influences both the power a person actually has to face challenges competently and the choices a person is most likely to make. These effects are particularly apparent, and compelling, with regard to behaviours affecting health [48].

Quantified Self[edit | edit source]

|

‘What gets measure gets managed’ – Peter Drucker – Management Consultant and Presidential Medal of Freedom, 2002. [49] |

In the past industries harped on understanding consumers and measuring their behaviour — today, consumers themselves are tracking and generating enormous amounts of data.

===QS - empowering the patient/individual quantified-self - healthcare revolution?===

“The quantified-self movement exposes the motivational effect on health behavioural change of quantitative measurement and analysis of personal health parameters. “ (Appelboom et al. 2014a). Technologies have become increasingly popular within the general population as self-tracking strategies, while health care professionals are eager to embrace the opportunities they perceive through using what has been dubbed ‘mhealth’ to promote the public’s health (Lupton 2013a). This electronic monitoring of human health behaviour is fast becoming an area of increasing research with a focus on ‘sensor fusion’ using single systems or devices (Lowe and OLaighin 2014).

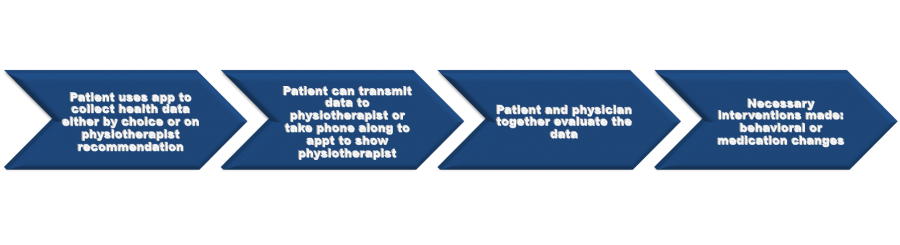

Utilising wearable systems for continuous monitoring is the key stone of the Quantified Self movement which aims to give a more accurate measure of human motion during day-to-day life [50]. These innovations are emerging for managing healthcare to revolutionize involvement of the healthcare professional and could increase the autonomy and patient involvement in terms of their health (Appelboom et al. 2014b) and hold potential to significantly benefit society [51]. A recent article in the Telegraph by the Health Minister Dr. Dan Poulter discusses how technology is driving improvement in personalised healthcare. A recent study by Vuori and colleagues (2013) remarked that the attitudes of physiotherapists for advising physical activity were amongst the most positive, and we have a key role to play in aiding behavior change to promote healthier lifestyles. As well as facilitating physiotherapists to take on the role as a lifestyle coach, these technologies can aid with monitoring chronically ill patients to reduce re-hospitalisation (Dobkin and Dorsch 2011). Appelboom and colleagues (2014c) refers to it as ‘Quantifying self hybrid models’ which essentially combine patient reported outcomes and tele-monitoring, i.e. integration of passive data collection and patients actively reporting, to reduce the subjective unreliance. Lupton (2013b) refers to it as ‘digitized health promotion’ and that these digital health technologies are advocated for drawing a renewed focus on personal responsibility for health.

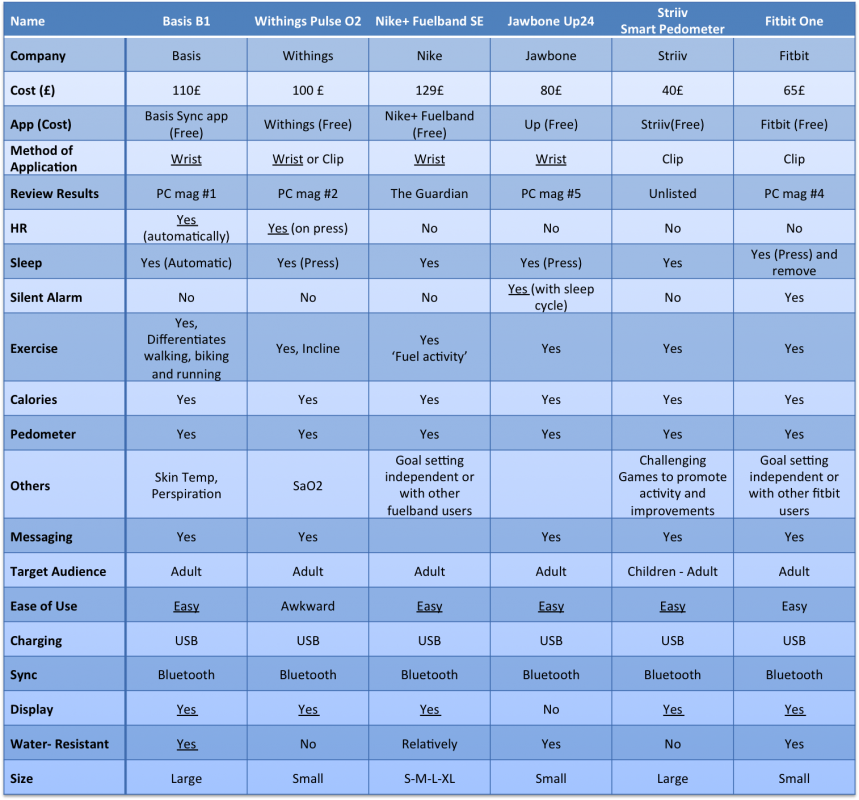

In line with the behaviour change models, once the patient adopts the appropriate technologies to engage in self-monitoring and self-care health can become more self-manageable (Lupton 2013b). However, survey research has reported that many health professionals are not themselves using mhealth in their professional practice to any great extent as yet, due to lack of knowledge about how best to do so or concern about having to learn about using new technologies (Hanson et al. 2011). This may be because little or no information is available to substantiate the validity of these consumer based activity monitors. Thus it is important to evaluate these devices so individuals and us as physiotherapists can make informed decisions (Lee et al. 2014).

An emerging trend- mhealth[edit | edit source]

Although currently dominating the market for self-tracking devices are the fitness-minded and tech-savvy individuals, it is apparent that there is increasing interest in expanding the use of outpatient monitoring as a strategy to improve healthcare delivery (Appelboom et al. 2014c). The drive towards this emerging technology trend for health promotion highlights the need for health professionals to embrace their use for helping patients to implement health behaviour change. They can provide a platform for the delivery of self management interventions that are highly customisable, low-cost and easily accessible (Estrin 2010). With reports on mhealth technologies being frequent within both the media and medical health literature due to the popularity of devices and related apps within the public (Lupton 2013). For example, the Apple App Store alone offers over 13,000 health-related apps (Strickland 2012), with estimations in 2012, of 44 million downloads worldwide for these apps (Raskin 2012). It is projected that by 2018, 485 million wearable devices will be sold annually (Drucker 2007). Furthermore a 2012 survey (Link to the survey findings) in the US of 3,000 adults, indicated that 85% owned a mobile phone, 53% were smartphones, 19% of people surveyed downloaded an app for health management. This emphasizes the emerging growth of mobile technologies as well as the use of smartphones for health and wellness (Ho 2013).

A major advantage with mhealth allows the health professional to monitor the patient during ADL’s and in a home environment. Frequently, problems faced by physiotherapists for patients with chronic diseases is measuring gains and losses in daily functioning over time, with the use of these sensor technologies for activity monitoring, it becomes possible to assess the effects of timing and dose of medication on physical functioning, addressing the level of activity gained throughout the day and maintenance of ADL’s, assess compliance with goals and instructions for exercise and skills practice and update instructions more frequently than an office visit (Dobkin and Dorsch 2011). The growth in uptake of these wearable fitness technologies provide an aid for health professionals to empower the patient in taking an active role in their health (Clarke and Steele 2012).

What devices does quantified self consist of?

What type of data can we collect?

However…

There are numerous examples in the literature illustrating the success of wearable technologies and online tools in increasing physical activity levels. However simply tracking an activity is not enough. Neither knowledge nor tracking alone immunizes you from an unhealthy lifestyle. The value of these devices crucially depend on the sophistication of the system it integrates with, which is highly dependent on the health knowledge of the system designer and the ability of that knowledge to translate through the system [52].

QS has enormous potential to help us be healthy and we’re just at the beginning stages of its ability to create meaningful change for individuals and populations.

Big Data (future benefits to the NHS) vs personal data[edit | edit source]

Overall we can break this down into two categories:

Big data = aggregate information on many people to yield population insights.

For example if the NHS were to coagulate data from a variety of people attempting to change their physical activity levels, this may help practitioners to facilitate other people’s behaviour change efforts more efficiently.

For example if the NHS were to coagulate data from a variety of people attempting to change their physical activity levels, this may help practitioners to facilitate other people’s behaviour change efforts more efficiently.

Personal data = best use is for implementing valid behaviour change modalities i.e. self-experimentation. The implementation of a smart health paradigm and then an awareness as to whether you are doing it and whether you are achieving your goals.

What does this all Mean?[edit | edit source]

As we now know self-efficacy is a key underlying factor and this requires two parts:

- Effective health paradigm e.g. ancestral health

- Effective behaviour modification techniques e.g. quantified self movement

Pursuing a healthy lifestyle has and always will require personal effort. However unlike the past being healthy requires a deliberate effort, which means intelligent choices, must be made on a day to day basis. However we can’t simply hand patients a device and expect that to do the trick. Therefore in order to succeed sustainable long lasting change there must be some personal intention and value empowered by the individual into the device and tools which they use to achieve their goal.

Being in a position of authority, Physiotherapists are empowered to assist patients to attribute value and in turn empower the devices and tools recommended to the patients and thus significantly affect behaviour change [53].

What about when the patient is on their own?[edit | edit source]

When patients are on their own it is important that they are provided by the Physiotherapist with the tools necessary to not only track their efforts but also to interpret this data in a meaningful way. Therefore the tool in question must be designed specifically to include a depth of theory which may facilitate behaviour change.

Online tools and devices have been found to be an effective means of increasing physical activity levels, however there is a need for more intensive theory-based interventions that incorporate multiple behaviour change techniques and modes of delivery. Without such interventions certain products have been found to be significantly less effective after 6 months [54]. The value of these devices crucially depend on the sophistication of the system it integrates with, which is highly dependent on the health knowledge of the system designer and the ability of that knowledge to translate through the system.

Human OS is an online tool which aims to support the daily health practice of its users. Multiple behavioral influences - like persuasion, social dynamics, feedback loops, triggers - are utilized in a system aimed to simplify a person's daily health practice. For example, having a daily workout sent to a patient lowers the burden on an individual to have to come up with a workout idea on their own, it primes the activity, and when entered in the tracker system, gives that patient and the Physiotherapist feedback as to how their current physical activity level compares to their exercise recommendations.

Current tools Available[edit | edit source]

Current Apps[edit | edit source]

Benefits of self tracking devices for patients

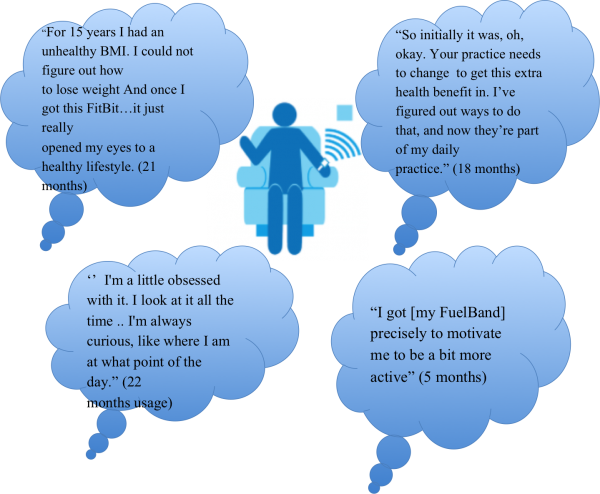

Fritz and colleagues (2014)[60] believes this technology has the ability to persuade and motivate people and undertook a study to determine user’s attitudes towards long term use of activity sensing devices for fitness. Fritz et al. (2014)[61] was aware that not all people who purchase devices such as, Nike fuelband and fitbit etc use them long term, however the aim of the study was to interact with people who have incorporated these devices into their daily routine with the view to understanding long term effects these devices may have [62]. According to Schull et al (2014) this long term monitoring is at the heart of the quantified-self movement as it can give an accurate understanding of human motion realities, which cannot be achieved during laboratory testing [63].

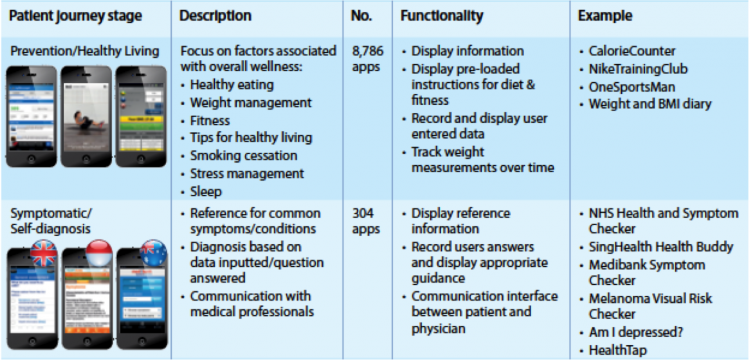

The IMS Institute for healthcare informatics (2013) through their publication, Patient apps for improved healthcare (Hyperlink) have outlined a detailed breakdown of current health apps available from Itunes library. There are apps available that cover the full patient journey, with healthy living apps accounting for the majority of apps consumed at the moment. Although some apps are either therapy area specific or demographic specific there are still areas in the app market that needs to be filled.

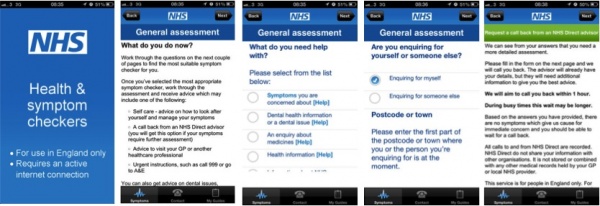

Currently, the NHS has started using smartphones and apps to help engage the public. Such as with the NHS Health and Symptom Checker, which allows users to to check their symptoms, get an assessment and information on their condition, and be given advice how to get better.

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-30027504

Future Practice[edit | edit source]

At the recent CSP Physiotherapy Conference 2014 delegates were asked: "Are physiotherapists the exercise specialists of choice for people with long-term conditions?", With the response being a resounding yes. Physiotherapist were described as being ideal in solving the dilemma of lack of adherence to exercise programmes.[66]

http://www.physio-pedia.com/Self_tracking

http://www.physio-pedia.com/Mobile_Apps

Conclusion[edit | edit source]

Modern humans have inherited a genome programmed for movement from a time when physical activity was obligatory for survival. Inactivity sets off a chain of molecular mechanisms that affect the way our cells communicate, which leads to disease including NMSK disorders. [67]

With the quantified self/wearable technology market growing momentum, the extremely low levels of physical activity and with the lack of resources available to Physiotherapists to assist with real tangible behaviour change; this is a hugely relevant area of potential research.

Recently there has been a growing focus on preventative approaches towards increasing levels of chronic disease. Physiotherapists are considered to be in an ideal position to help with this mission during their consultations, however little training and/or resources are provided to enable them to do this in an effective way [68].

Current literature states that there is a need for more intensive theory-based interventions that incorporate multiple behaviour change techniques. To our knowledge, Human OS is the only online tool currently available which incorporates multiple behaviour change techniques capable of supporting the daily health practice of its users in the long term. In an age where NMSK conditions linked to physical inactivity are significantly increasing, Physiotherapists will be increasingly expected to assume the role of a health coach. This page was designed to illustrate the problem at hand but more importantly the way forward [69].

Recent Related Research (from Pubmed)[edit | edit source]

Extension:RSS -- Error: Not a valid URL: Feed goes here!!|charset=UTF-8|short|max=10

References[edit | edit source]

References will automatically be added here, see adding references tutorial.

- ↑ WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION., 2014. Health Topics Physical Activity. [online]. [viewed 29 October 2014]. Available from: http://www.who.int/topics/physical_activity/en/

- ↑ NHS HEALTH SCOTLAND. 2012. Costing the Burden of Ill Health Related to Physical Inactivity for Scotland. [online]. [viewed: 06 November 2014]. Available from: http://www.healthscotland.com/uploads/documents/20437-D1physicalinactivityscotland12final.pdf.

- ↑ JANSSEN, I., 2012. Health Care Cost of Physical Inactivity in Canadian Adults. Applied Physiology, Nutrition and Metabolism. [online]. Vol. 37. 803-806. [viewed: 06 November 2014]. Available From: http://www.nrcresearchpress.com/doi/pdf/10.1139/h2012-061

- ↑ JINGUAN, L., 2013. Improving Chronic Disease Self-Management through Social Networks. Population Health Management. 16 (5), pp. 285-287.

- ↑ Dr Mike Evans. 23 and 1/2 hours: What is the single best thing we can do for our health?. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aUaInS6HIGo [last accessed 30/10/14]

- ↑ WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION., 2014. Health Topics Physical Activity. [online]. [viewed 29 October 2014]. Available from: http://www.who.int/topics/physical_activity/en/

- ↑ WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION., 2014. Health Topics Physical Activity. [online]. [viewed 29 October 2014]. Available from: http://www.who.int/topics/physical_activity/en/

- ↑ WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION., 2014. Health Topics Physical Activity. [online]. [viewed 29 October 2014]. Available from: http://www.who.int/topics/physical_activity/en/

- ↑ WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION., 2014. Health Topics Physical Activity. [online]. [viewed 29 October 2014]. Available from: http://www.who.int/topics/physical_activity/en/

- ↑ WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION., 2014. Health Topics Physical Activity. [online]. [viewed 29 October 2014]. Available from: http://www.who.int/topics/physical_activity/en/

- ↑ WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION., 2014. Health Topics Physical Activity. [online]. [viewed 29 October 2014]. Available from: http://www.who.int/topics/physical_activity/en/

- ↑ Hugh Saunders. National Physical Activity Guidelines. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=srpxGX0M5bE [last accessed 30/10/14]

- ↑ CSEP THE GOLD STANDARD IN EXERCISE SCIENCE AND PERSONAL TRAINING. 2014. Canadian Physical Activity Guidelines and Canadian Sedentary Behaviour Guidelines. [online]. [viewed 06 November 2014]. Available from: http://www.csep.ca/english/view.asp?x=804

- ↑ GOV.UK.2014. Guidance UK Physical Activity Guidelines. [online]. [viewed 06 November 2014]. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/uk-physical-activity-guidelines

- ↑ Health.2014. The United States of America Physical Activity Guidelines. [online]. [viewed 06 November 2014]. Available from:http://www.health.gov/paguidelines/guidelines/

- ↑ BROWNELL, KD., 2010. The humbling experience of treating obesity: Should we persist or desist? Behaviour Research Therapy 48(8), pp. 717–719.

- ↑ DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH. 2012. Long Term Compendium of Information Third Edition. [online]. [viewed 03 November 2014]. Available from: http:// tinyurl.com/m9zyqe8

- ↑ OLIVEIRA, V.C., FERREIRA, P.H., MAHER, C.G., PINTO, R.Z., REFSHAUGE, K.M. and FERREIRA, M.L., 2012. Effectiveness of self‐management of low back pain: Systematic review with meta‐analysis. Arthritis Care &amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp; Research. 64(11), pp. 1739-1748

- ↑ HARDING, V. and WATSON, P.J., 2000. Increasing activity and improving function in chronic pain management. Physiotherapy. 86(12), pp. 619-630.

- ↑ SWAN, M. 2012. Sensor mania! The internet of things, wearable computing, objective metrics and the quantified self. Journal of Sensor and Actuator Networks 1 (3),pp. 217-253.

- ↑ LORIG, KR. and HOLMAN, H. 2003. Self-management education: history, definition, outcomes, and mechanisms. Annals of Behavioural Medicine. 26 (1), pp. 1–7.

- ↑ PHILLIPS, J. 2012. The need for an integrated approach to supporting patients who should self-manage. Self-Care 3(2), pp. 33–41

- ↑ HEALTH FOUNDATION., 2011. The Health Foundation Evidence: Helping People Help Themselves [online]. . [Viewed 06 Nov 2014] Available from: http://renaltsar.blogspot.co.uk/2011/12/what-is-selfmanagement-support.html

- ↑ BOS, C., VAN DER LANS, IA., RIJNSOEVER, FJ., VAN TRIJP, HC., 2013. Understanding consumer acceptance of intervention strategies for healthy food choices: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health 13: 1073.

- ↑ PENG, K., BOURRET, D., KHAN, U., TRUONG, H., NIXON, S., SHAW, J. and MCKAY, S., 2014. Self-Management Goal Setting: Identifying the Practice Patterns of Community-Based Physical Therapists. Physiotherapy Canada. 66(2), pp. 160–168

- ↑ HARDING, V. and WATSON, P.J., 2000. Increasing activity and improving function in chronic pain management. Physiotherapy. 86(12), pp. 619-630

- ↑ Decisions Skills. Smart Goals - Overview. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1-SvuFIQjK8 [Last Accessed:7/11/14]

- ↑ CROWE, M., WHITEHEAD, L., JO GAGAN, M., BAXTER, D. and PANCKHURST, A., 2010. Self‐management and chronic low back pain: a qualitative study. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 66(7), pp. 1478-1486.

- ↑ PROCHASKA, JO., DICLEMENTE, CC., NORCROSS, JC., 1992. In search of how people change: Applications to addictive behaviours. American Psychologist 47(9), pp. 1002–1114

- ↑ THE CHARTERED SOCIETY OF PHYSIOTHERAPY. 2014. Neuroscience: Why do ignore what I some of my patients say? Understanding Pain and Behaviour [online] London: [viewed on 6th Nov 2014]. Available from: http://www.csp.org.uk/events/neuroscience-why-do-some-my-patients-ignore-what-i-say-7-may-2014-london

- ↑ KAWI, J., 2014. Predictors of self-management for chronic low back pain. Applied Nursing Research. [online]. [viewed 06 April 2014]. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.apnr.2014.02.003

- ↑ COOPER, K., SMITH, B.H. and HANCOCK, E., 2009. Patients’ perceptions of self-management of chronic low back pain: evidence for enhancing patient education and support. Physiotherapy. 95(1), pp. 43-50.

- ↑ http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ph6/chapter/2-considerations#definitions

- ↑ Cooper, S., and Ratele, K. 2014. Psychology serving humanity: Proceedings of the 30th International Congress of Psychology, Volume 2: Western psychology.

- ↑ Cooper, S., and Ratele, K. 2014. Psychology serving humanity: Proceedings of the 30th International Congress of Psychology, Volume 2: Western psychology.

- ↑ Cooper, S., and Ratele, K. 2014. Psychology serving humanity: Proceedings of the 30th International Congress of Psychology, Volume 2: Western psychology.

- ↑ Cooper, S., and Ratele, K. 2014. Psychology serving humanity: Proceedings of the 30th International Congress of Psychology, Volume 2: Western psychology.

- ↑ Skinner, B, F., and Holland, J, G. 1961. The analysis of behavior: A program for self-instruction. New York, US, McGraw-Hill.

- ↑ Skinner, B, F., and Holland, J, G. 1961. The analysis of behavior: A program for self-instruction. New York, US, McGraw-Hill.

- ↑ Fjeldsoe, B., et al. 2011. Systematic review of maintenance of behavior change following physical activity and dietary interventions. Health Psychology, 30(1), pp.99-109.

- ↑ http://www.fw.msu.edu/outreachextension/thetheoryofreasonedaction.htm

- ↑ http://www.uky.edu/~eushe2/Bandura/Bandura1998PH.pdf

- ↑ http://www.utwente.nl/cw/theorieenoverzicht/theory%20clusters/health%20communication/theory_planned_behavior/

- ↑ Prochaska, J. O., Velicer, W. F., Rossi, J. S., Goldstein, M. G., Marcus, B. H., Rakowski, W., Fiore, C., Harlow, L. L., Redding, C. A., Rosenbloom, D., &amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp; Rossi, S. R. (1994). Stages of change and decisional balance for twelve problem behaviors. Health Psychology, 13, 39-46.

- ↑ http://userpage.fu-berlin.de/health/hapa.htm

- ↑ http://www.behaviormodel.org/

- ↑ UTAH County Well 4 Life.2014. Positive Attidue Development Workshop. [Online] Available at: http://utahcountywell4life.blogspot.co.uk/2014/02/positive-attitude-development-workshop.html Last Accessed 5/11/14

- ↑ Bandura, A. (1977). Self-Efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavior change. Psychological Review, 84, 191-215

- ↑ Peter Drucker. Management Consultant and Presidential Medal of Freedom. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V08dWCtDyd8 [last accessed 4/11/14]

- ↑ SHULL, P.B., JIRATTIGALACHOTE, W., HUNT, M.A., CUTKOSKY, M.R., and DELP, S.L. 2014. Quantified self and human movement: A review on the clinical impact of wearable sensing and feedback for gait analysis and intervention, Gait and Posture, vol. 40, pp. 11-19.

- ↑ SHULL, P.B., JIRATTIGALACHOTE, W., HUNT, M.A., CUTKOSKY, M.R., and DELP, S.L. 2014. Quantified self and human movement: A review on the clinical impact of wearable sensing and feedback for gait analysis and intervention, Gait and Posture, vol. 40, pp. 11-19.

- ↑ Legris, P., et al. 2003. Why do people use information technology? A critical review of the technology acceptance model. Information and Management, 40(3), pp.191-204.

- ↑ Moffet et al.1997.The influence of the physiotherapist-patient relationship on pain and disability

- ↑ Fjeldsoe, B., et al. 2011. Systematic review of maintenance of behavior change following physical activity and dietary interventions. Health Psychology, 30(1), pp.99-109.

- ↑ https://www.fitbit.com/uk

- ↑ http://www.nike.com/gb/en_gb/c/nikeplus-fuelband

- ↑ http://jawbone.com/up

- ↑ http://www.mybasis.com

- ↑ Duffy, J. 2014. The Best Activity Trackers for Fitness. PC Mag. [Online} Available at http://www.pcmag.com/wearables?__rmid=the-5-best-smartwatches-515863437.html Last accessed: 5/10/14

- ↑ FRITZ, T., HUANG, E,M., MURPHY, G, C, and ZIMMERMANN, T. 2014. Persuasive Technology in the Real World: A Study of Long-Term Use of Activity Sensing Devices for Fitness, CHI, pp. 1-10.

- ↑ FRITZ, T., HUANG, E,M., MURPHY, G, C, and ZIMMERMANN, T. 2014. Persuasive Technology in the Real World: A Study of Long-Term Use of Activity Sensing Devices for Fitness, CHI, pp. 1-10.

- ↑ FRITZ, T., HUANG, E,M., MURPHY, G, C, and ZIMMERMANN, T. 2014. Persuasive Technology in the Real World: A Study of Long-Term Use of Activity Sensing Devices for Fitness, CHI, pp. 1-10.

- ↑ SHULL, P.B., JIRATTIGALACHOTE, W., HUNT, M.A., CUTKOSKY, M.R., and DELP, S.L. 2014. Quantified self and human movement: A review on the clinical impact of wearable sensing and feedback for gait analysis and intervention, Gait and Posture, vol. 40, pp. 11-19.

- ↑ https://developer.imshealth.com/Content/pdf/IIHI_Patient_Apps_Report.pdf

- ↑ https://developer.imshealth.com/Content/pdf/IIHI_Patient_Apps_Report.pdf fckLR

- ↑ CSP. Physio 14: Physio's are the exercise specialists of choice, delegates say. Available from:http://www.csp.org.uk/news/2014/10/11/physio-14-physios-are-exercise-specialists-choice-delegates-say [last accessed 30/10/14]

- ↑ Booth, F.W., Chakravarthy, M.V. and Spangenburg, E.E. 2002. Exercise and gene expression: physiological regulation of the human genome through physical activity. The Journal of physiology, 543 (Pt 2) Sep 1, pp.399-411.

- ↑ Harding, V., and Williams, A, C. 1995. Applying Psychology to Enhance Physiotherapy Outcome. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice, 11(3), pp. 129-132.

- ↑ Bort-Roig, J., Gilson, N.D., Puig-Ribera, A., Contreras, R.S. and Trost, S.G. 2014. Measuring and Influencing Physical Activity with Smartphone Technology: A Systematic Review. Sports Medicine, 44 (5) pp.671-686