Rotator Cuff

Original Editor - Florence Brachotte

Top Contributors - Els Van Haver, Amanda Ager, Admin, Kim Jackson, Naomi O'Reilly, Uchechukwu Chukwuemeka, George Prudden, Vidya Acharya, Joao Costa, Tony Lowe, Wendy Walker, Oyemi Sillo, WikiSysop, Fasuba Ayobami, Rachael Lowe and Florence Brachotte

Description[edit | edit source]

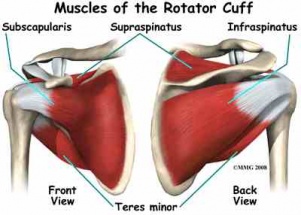

The Rotator Cuff (RC) is a common name for the group of 4 distinct muscles and their tendons, which provide strength and stability during motion to the shoulder complex. They are also referred to as the SITS muscle, with reference to the first letter of their names (Supraspinatus, Infraspinatus,Teres minor, and Subscapularis, respectfully). The muscles arise from the scapula and connect to the head of the humerus, forming a cuff around the glenohumeral (GH) joint.

Anatomy[edit | edit source]

The rotator cuff muscles include: [1]

| Origen on scapula | Insertion on humerus | Primary function | |

|---|---|---|---|

| M. supraspinatus | supraspinous fossa | superior facet of greater tuberosity | abduction |

| M. infraspinatus | infraspinous fossa | middle facet of greater tuberosity | exorotation

(lateral / external rotation) |

| M. teres minor | lateral border of scapula | inferior facet of greater tuberosity | exorotation

(lateral / external rotation) |

| M. subscapularis | subscapular fossa | lesser tuberosity or humeral neck | endorotation

(medial / internal rotation) |

Cranial to the rotator cuff, there is a bursa which covers and protects the muscle and tendons, as they are in close contact to the surrounding bones.

Function[edit | edit source]

The RC muscles are each used in a variety of upper extremity movements including flexion, abduction, internal rotation and external rotation. They are essential players in almost every type of shoulder movement. Balanced strength and flexibility in each of the four muscles are vital to maintain functioning of the entire shoulder girdle.

As a group, the rotator cuff muscles are responsible for stabilizing the shoulder joint, by providing the "fine tuning" movements of the head of the humerus within the glenoid fossa. They are deeper muscles and are very active in the neuromuscular control of the shoulder complex during upper extremity movements.

They keep the head of the humerus within the small glenoid fossa of the scapula in order to enlarge the range of motion in the GH joint and avoid mechanical obstruction (i.e. a possible biomechanical impingement during elevation).[1][2]

Common Injuries to the Rotator Cuff[edit | edit source]

RC injuries are common injuries that can occur at any age. In younger subjects, most injuries occur secondary to trauma or arise from overuse due to overhead activities (e.g. volleyball, tennis, pitching). Incidence of injuries increases with age, however some individuals with rotator cuff pathology may be asymptomatic.[2][3] The RC muscles can fall victim to muscle degeneration, impingement and tearing with advancements in age. Poor biomechanics, such as postural dysfunctions can prematurely affect the quality of the RC muscles and tendons due to repetitive strains and tissue encroachment.

Most common injuries to the Rotator Cuff are often referred to as:

Diagnosis of Rotator Cuff Pathologies[edit | edit source]

Key elements in diagnosing rotator cuff pathology are:[4]

- History

- Physical Examination

- X-rays

- MRI or

- US

It is important to differentiate shoulder pain coming from places other than the shoulder, such as the neck or elbow and also pains from other structures at the shoulder, through anamnesis and physical examination. Pain is mostly provoked by overhead maneuvers and weakness of the shoulder muscles may occur.

Rotator cuff muscles can not be seen on X-rays but calcifications, arthritis or bone deformations - that are common causes for rotator cuff pathologies - may be visible. The most common imaging method to evaluate rotator cuff pathologies is MRI. It can detect tears and inflammation and may help to determine size and character in order to establish a proper treatment protocol.

Although, MRI is the gold standard imaging method for rotator cuff pathologies, US can be used as it has a good diagnostic accuracy (Evidence level 2a)[5], more cost effective and readily available[6][7].

Resources[edit | edit source]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Gray,H. Anatomy of the Human Body. Philadelphia: Lea and Febiger, 1918; Bartleby.com, 2000

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Codman EA. The shoulder. Malibar, Florida: R.E. Kreiger; 1934

- ↑ Matsen FA 3rd. Clinical practice. Rotator-cuff failure. N Engl J Med. 2008;358: 2138-47. http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMcp0800814

- ↑ Jia X, Petersen SA, Khosravi AH, Almareddi V, Pannirselvam V, McFarland EG. Examination of the shoulder: the past, the present, and the future. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:10-8.

- ↑ Lenza, M, Buchbinder, R, Takwoingi, Y, Johnston, RV, Hanchard, NC, Faloppa, F. Magnetic resonance imaging, magnetic resonance arthrography and ultrasonography for assessing rotator cuff tears in people with shoulder pain for whom surgery is being considered. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013; DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD009020.pub2

- ↑ Day, M, Phil, M, McCormack, RA, Nayyar, S, Jazrawi, L. Physician Training Ultrasound and Accuracy of Diagnosis in Rotator Cuff Tears. Bulletin of the hospital for joint disease(2013). 2016; 74(3):207-11.

- ↑ Thakker, VD, Bhuyan, D, Arora, M, Bora, MI. Rotator Cuff Injuries: Is Ultrasound Enough? A Correlation with MRI. International Journal of Anatomy, Radiology and Surgery. 2017; Vol-6(3): RO01-RO07. DOI: 10.7860/IJARS/2017/28116:2279