Psychological Basis of Pain

- Please do not edit unless you are involved in this project, but please come back in the near future to check out new information!!

- If you would like to get involved in this project and earn accreditation for your contributions, please get in touch!

Tips for writing this page:

- Describe and explain current theories of the psychological basis of pain for example: fear avoidance, pain-related anxiety, pain catastrophising, stress and learned helplessness

- How might these impact upon a pain experince?

- If you feel some of these points shoudl be an article of thier own, which you woudl like to write, please get in touch!

Original Editor - Add a link to your Physiopedia profile here.

Top Contributors - Sharine Balicanta, Richard Benes, Kim Jackson, Jo Etherton, Tarina van der Stockt, Shaimaa Eldib, Admin, Simisola Ajeyalemi, Lauren Lopez, Jess Bell, 127.0.0.1, Rachael Lowe, Evan Thomas, George Prudden, Kai A. Sigel and Luciana Segantin Lopes

Introduction[edit | edit source]

The IASP definition of pain highlights the multidimensional complexity of the painful experience. An individual’s belief systems, pain understanding, thoughts & emotions (anxiety, depression, catastrophizing) influence how the brain interprets a noxious stimulus in realtion to the meaning and level of threat the stimlus poses to wellbeing, and thereby influences the resulting output from the brain..including resulting behaviour (i.e. avoidance)[1]. To understand and manage pain, a physiotherapist must understand how and why psychological factors such as fear avoidance, catastrophizing, pain-related anxiety, stress and learned helplessness can impact upon a pain experince and a pateints coping stratergies. While this is unlikely to be an exclusive list of influenctial psychosocial factors, these are well reserched and evidenced. This page will review each of them in turn.

Fear avoidance

DEFINITION

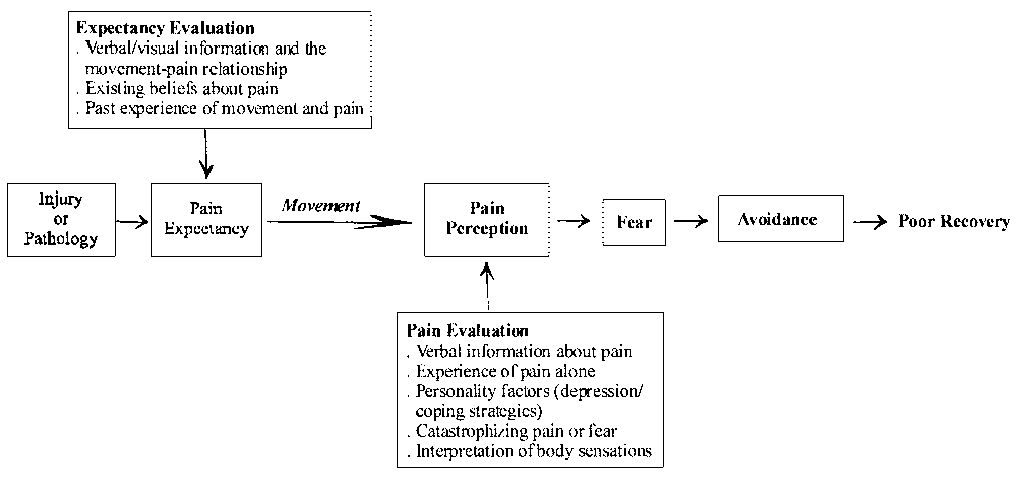

Pain and Fear Fear is a typical emotional response to an experience that is percieved to be threatening, such as one that leads to a pain sensation [2][3]. Future avoidance of the painful activity is often the resulting behviour adopted to protect oneself ftom a repeat of the fearful emotion and painful experince. This pattern can lead to fear and aviodance of work-related activities, movement, and re-injury [3]. 'Fear-avoidance' refers to the” avoidance of movements or activities based on pain-related fear”. Kinesophobia is another term used in literature to refer to this behavior This is defined as “an excessive, irrational, and debilitating fear of physical movement and activity resulting from a feeling of vulnerability to painful injury or reinjury.”[4]. Fear avoidance theorised as a factor that can maintain the painful experience despite the absence of physiological damage [5].

IMPACT OF FEAR AVOIDANCE ON PAIN RESPONSE

Fear avoidance in an acute injury, a normal response?

In acute injury or acute painful experience, intrinsic levels of fear may elevate as fear is a natural consequence of pain [6]. The individual may rest and protect the painful area as an adaptive behaviour which may be helpful during this acute stage when healing of injured tissues needs to happen [6] As the acute level of pain reduces, it has been suggested that individuals who confront their fears are able to resume normal activities and extinguish their fears [2]. For those whose fear avoidance response persists, it has been proposed that a cycle of continued avoidance of activities, aggravation of fear avoidance behaviors and disability ensues[1].

How does fear avoidance persist? '

The following models proposed to explain how fear avoidance persists for some people, and how it impacts on pain, behaviour and disability. .

In the fear-avoidance model of pain [1], the individuals who catastrophically interpret the painful experience will be:

• more fearful of pain

• more attentive to possible signals of threat (hypervigilance)

• likely to misinterpret normal somatic sensations as pathological (somatisation).

• have associated negative affectivity (the general tendency to experience subjective distress and dissatisfaction)

In this model, catastrophizing is a prerequisite to the development of fear avoidance behaviour [7]. With negative appraisals of the pain, fear avoidance behaviors are elicited [8]. Due to hypervigilance, the avoidance behaviour begins to occur in anticipation rather than in response to pain [1][3] As there are fewer and fewer opportunities to correct the wrongful association of pain with the avoided activity, the behaviour perpetuates itself and fear avoidance persists [1].

Fear avoidance and disability

The pathway to disability can be through the following means:

• Increased anticipation of pain leads to poorer performance of activities, which can be the pathway to disuse [3] and disability.

• Increased attention to pain has been reported to cause difficulty to focus on ongoing, non-painful tasks [8]

If this model is to be followed, it would be helpful to screen for high levels of fear avoidance and catastrophizing in the early stages of pain to determine those at risk for the fear avoidance behaviour to persist.

Fear avoidance model and chronic pain

This model has also been proposed primarily as mechanism for how pain is maintained in chronic low back pain. Where fear avoidance may serve a protective function in the acute phase of injury, persistent reliance on fear avoidance to cope with persistent pain could be considered maladaptive, and a potential barrier to recovery [6] .

The following mechanisms have been cited [6][1][3][8] by which fear avoidance can maintain the pain experience in patients with chronic pain

• increased physiological arousal/heightened muscle reactivity

• associated anxiety and hypervigilance leads to increased attention to expected painful stimulus which in itself can intensify the pain

• Persistent avoidance becomes self-perpetuating due to lack of opportunities to correct the wrongful association of pain with movement; promoting disability and disuse;disuse can further worsen the pain problem

• Reduced participation in valued activities like work, leisure and social contacts can lead to mood changes like irritability, frustration and depression. These mood changes could further affect perception of pain

• Disuse or disability from persistent avoidance behavior can reduce threshold for experiencing future pain

Research has shown an association of fear avoidance and pain related fears [9][10][11][12][13][14] even when pain intensity and other variables were controlled in patients with chronic pain. There is ongoing research aiming to prove the application of fear avoidance model on the acute stage of low back pain. Some researches showed that high levels of fear avoidance in this stage can be a predictor for future episodes of pain [15][16][17][18][19]. There are researches that has contrary results suggesting that fear avoidance in the early stages of injury may not be may a path for future disability and pain[7][20][10].

In the learning pathway model, fear avoidance becomes a conditioned response through association of pain with movement [1][2][7]. The behaviour of avoiding expected pain-provoking movement or activities to prevent new episodes of pain is learned through experience [21]. The individual may anticipate similar experiences and associate non-painful or nonharmful experiences with pain [2] resulting in persistent fear avoidance behavior.

The following factors can affect the strength of association of pain with movement and the conditioned fear avoidance response [6][1][7] )

• existing beliefs about pain and the meaning of the symptoms

• beliefs about their own ability to control pain (self-efficacy)

• prior learning experiences (either direct experience or observational learning)

• expectations of recovery

• current emotional states (which include catastrophizing, anxiety, depression)

This model can support classification of fear-avoiders[2] to

• misinformed avoiders who have misinformed beliefs about movement and risk for damage or re-injury; may benefit from right information about pain and movement

• learned avoiders who learned the behaviour without being aware nor overly distressed about it; may benefit from gradual exposure to activity depending on pain tolerance

• affective avoiders who are distressed and have strong negative cognitions about the pain; may need more cognition-based management and challenge beliefs

Anxiety and Depression

DEFINITION

Anxiety

- Anxiety is described as a general term for several disorders that include; uneasiness, apprehension, nervousness, fear and worrying.

- <span style="line-height: 1.5em;" />

- There is high prevalence of anxiety reported throughout the literature in patients with chronic pain syndromes of varying nature including; non-specified/widespread chronic pain [22][23][24][25][26][27], low back pain [23][28], traumatic musculoskeletal injury (TMsI)[29][30], rotator cuff tear [31] and also in non-musculoskeletal(MSK) conditions such as; phantom limb pain [32], prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome[33] and diabetic neuropathy[34].

- The prevalence of patients in each study purely with anxiety varied throughout, from 18%[25] to 72% [24] of those recruited. Unfortunately much of this literature does not solely focus on anxiety alone.

- The following have been commonly reported anxiety symptoms reported in patients with chronic pain[28]; “not being able to stop worrying”, “worrying about too many different things” and “feeling as though something awful might happen”.

A study[26] which aimed to evaluate the prediction of chronic pain looked at anxiety, depression and social stressors as risk factors and the severity of pain at 3, 6 and 12 months in 250 patients. They found a strong correlation between baseline anxiety which predicted pain severity at 12 months. Interestingly no correlation was found for social stressors or depression.

TMsI has been shown to correlate strongly with persistence of pain and incidence of psychiatric disorders. A systematic review of 12 studies[29] noted anxiety as one of several predictive factors of persistence of pain of up to 84 months post injury.

In another TMsI study[30] anxiety was found to predict pain intensity at different timeframes post injury whereas depression, social support, length of hospital stay and self-efficacy had no substantial effect. They summarised that pain predicted anxiety and depression in the first year, but anxiety only predicted pain intensity from 12-24 months. Anxiety symptoms were therefore hypothesised as the primary causative factor of persistent pain in this cohort study.

In the literature several materials have been used in screening for and assessing anxiety; Hospital Anxiety and Depression (HAD) scale, Beck Anxiety Inventory, Stait-trait Anxiety Inventory, Distress Risk Association Questionnaire, Brief Symptom Inventory and Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item Scale.

One study examined the validity of a single question to screen for depression and anxiety[35].

• Single question screening tools were compared with validated questionnaires such as mini-international neuropsychiatric interview, HAD scale and Hopkins symptom checklist.

• It was found that the single questions demonstrated fair ability to detecting anxiety with a sensitivity of 68% and a good ability to exclude anxiety with a specificity of 85%.

• Therefore single question screening tools are fairly effective in identifying anxiety and could be utilised into early assessments with chronic pain patients.

Depression

Depression is described as a general term for mental disorders which include; sadness, loss of interest or pleasure, feelings of low self-worth and low mood.

- The prevalence of depression is also significant in varying chronic pain syndromes.

- It is also suggested that gender role and sex differences may act as a mediator, with higher prevalence of female sufferers compared to males[22]. Furthermore women tend to report greater levels of catastrophising behaviour compared to men[22].

- Unfortunately, some of the literature fails to differentiate between anxiety, stress, depression and distress meaning much of the analysis is focused on assessing or treating these symptoms together.

- Some frequently reported depressive symptoms among chronic pain patients are; “thinking of suicide/self harm” and “feeling down, depressed or hopeless”[28].

- In the literature obtained for this review, depression alone is associated with; chronic MSK[36] and widespread pain [24][25], knee pain[37], low back pain [23][28] and chronic pelvic pain/prostatitis[33][38].

- In a study examining the impact of anxiety and depression in phantom limb pain (PLP) patients[32] mean depression scores were higher, although non-significant, in patients with non-PLP chronic pain syndromes.

In TMsI subjects[30] depression scores did not predict pain severity at any stage over 0-24 months post injury.

Contrastingly, in a systematic review of TMsI[28] depression was a predictive factor of persistent pain along with other cognitive and behavioural factors.

A study of low back pain[28] observed higher prevalence of depression symptoms (13.7%) compared to anxiety symptoms (9.5%).

Similarly, a cohort of 400 patients with chronic myofascial or neuropathic pain demonstrated higher prevalence of depression (93%) than anxiety (72%)[24], however this was contradicted by opposing findings in 400 chronic pain patients (pathology not given) with higher observed levels of anxiety (70%) compared to depression (60%)[25] although depression was reported at a ‘non-significant level’.

Pain, Anxiety and Depression

- Anxiety and depression appear to be overlapping conditions. Much of the literature has acknowledged their joint effect in chronic pain patients[25][27][31][33][39].

o A study which looked into risk factors for chronic widespread pain[39] reported higher levels (87%) of persistent pain in patients with both anxiety and depression compared to in isolation (35% & 66% respectively).

o Furthermore a study in Brazil[25] which included 400 chronic pain patients observed 54% with both of the psychiatric disorders compared to anxiety (18%) or depression (7%) alone.

- It presents an even more catastrophic problem when these two psychiatric disorders present together with pain as various studies have noted that function and quality of life is more severely impaired by pain than in the conditions in isolation.

o Castro et al,[25] observed a significant difference in QoL reflected in all aspects of the short-form 36 questionnaire; indicating more severe impairments in vitality, mental health & physical, emotional and social functioning when the two conditions presented together with pain.

o In patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain[27], those with both anxiety and depression experienced the greatest pain severity, a highly significant finding. Furthermore combined psychiatric co-morbidity was strongly associated with disability days with; 18.1 days in pain only patients, 32.2 in those with pain and anxiety, 38.0 days in those with pain and depression and 42.6 days in those with all three conditions. This study also found a significant correlation with reduced QoL when all three conditions presented together.

o In 85 patients with rotator cuff tears of the shoulder[31] distressed patients showed a significant association with higher Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) scores, lower simple shoulder test and shoulder and elbow scores indicating higher perceived pain and disability. Interestingly other variables such as tear size and classification, age, sex, BMI and smoking status were non-significant. Unfortunately the ‘Distress Risk Assessment Method Questionnaire’ used in this study did not distinguish between anxiety and depression symptoms as the questionnaire includes symptoms of both conditions together, making it difficult to identify the effect of either condition simultaneously.

- The findings of mixed psychiatric co-morbidity appear to extend to non-MSK pathologies such as chronic prostatitis/pelvic pain syndrome;

• In this study[33] significantly higher HAD scores were found in the 55 patient intervention group compared to the 58 patient control group.

• There was a significant relationship in the patient group between QoL, pain with the GARS (stress item) scale which assessed the work, personal, financial roles of the individuals as well a sickness perception.

Thus it comes into question as to why these psychiatric disorders;

a) present together,

b) develop with the onset of traumatic pain,

c) appear to cause acute pain to persist and

d) cause more severe functional deficit together than when presenting independently.

Many studies have looked into the pathophysiology of pain, anxiety and depression to find answers and to facilitate more successful treatment of these complex conditions.

IMPACT OF ANXIETY AND DEPRESSION ON THE PAIN EXPERIENCE

Anxiety

A physiological model of anxiety may explain its role in pain perception;

• It is known that a state of acute anxiety stimulates the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) causing increased muscle tension, increased nociceptive input and increased sensitivity to pain stimuli [22][26], thus explaining why anxiety may correspond to increased pain perception.

• Corticosteroid hormones, for example, released after stress may play a part in pain modulation[40] as cortisol (a steroid hormone known to stimulate the SNS) has been found in higher levels in those with chronic pain[41].

• Furthermore neurotransmitters, neuropeptides and pro-inflammatory cytokines have been found to either mediate or modulate pain[26]. Therefore these physiological processes overlap in both anxiety and pain.

• There is evidence accumulating to show atypical sensory processing in the brain and dysfunction of skeletal muscle nociception[40], however the latter may not explain pain persistence in non-MSK pathologies where chronic pain has clearly been observed.

• The “pain matrix”[14], responsible for modulation of pain signals in the central nervous system (CNS), shares elements with brain networks responsible for stress, identifying another connection to the SNS.

Pain contributes to feelings of anxiety due to fear of the cause and if this persists a state of hypervigilance and avoidance behaviours may develop as a “maladaptive” coping response[22].

• A more permanent state of anxiety results in chronic muscle tension and anticipatory anxiety which leads to even more disability.

• Decreases in activities, especially those which provide meaning and reinforcement, may result in greater social isolation, decreased self-efficacy, increased feelings of uselessness and subsequent increases in anxiety and depression symptoms[22].

• This theory is closely interlinked with the ‘fear-avoidance’ model, a cycle prospected to play a vital part in sustenance of pain behaviours and has been shown to be an independent predictor of pain severity and disability among those with MSK pain[26].

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies along with blood-oxygenated level dependent contrast (BOLD) techniques have been utilised in various studies to map common areas of brain activation by detecting changes in blood flow.

These studies have been able to map similar areas of brain activation for anxiety and pain[26]. It has been shown that there is exaggerated brain response in patients with social anxiety disorder[42][.

• In one study[42] these methods were used to identify highlighted areas in the brain when anxious patients reacted to negative self-beliefs.

• The areas identified were the midline cortical regions such as; the ventromedial pre-frontal cortex (PFC), dorsomedial PFC, posterior cingulate cortex (implicated in self-referential process), emotional centre (amygdala) and memory area (hippocampal gyrus)[42].

• This indicates that there are integrated neural pathways associated with anxiety, pain processing, memory and concept of the self – the latter potentially implicating personality traits into anxiety and pain.

Depression

There is less known evidence about the physiology of depression compared to anxiety however it has been postulated that people with depression or a depressive personality have a greater sensitivity to acute and chronic pain[22].

- Similarly to anxiety, excessive sympathetic activity and elevated pro-inflammatory cytokine production is also postulated in the aetiology of depression[34] thus providing a potential physiological link between all three conditions and a possible reason for the overlapping prevalence within patient presentations.

fMRI studies have been conducted in patients with depressive disorders and similar findings have been identified as in anxious patients;

• In diabetic patients with depression, similar brain activation was identified in both neuropathic and non-neuropathic pain patients[34]; these were PFC, thalamus, insula and anterior cingulate cortex.

• Despite these CNS observations It is known that in healthy, non-depressed human volunteers pain-intensity related haemodynamic changes have been observed in all of the above brain sites[43]

Further studies compared the response of brain areas with BOLD techniques;

• 13 patients suffering from an acute episode of major depressive disorder (MDD) were investigated during painful stimulus application and compared to 13 control subjects[44].

• The results demonstrated increased activation of the pain matrix and increased thermal pain thresholds compared to healthy subjects.

• They speculated that the brain area activation may be linked to an underlying prefrontal psychopathology in depression.

• In another BOLD study[45] patients with diagnosed MDD showed greater activation of pain-related brain sites (right insular, dorsal anterior cingulate, right amygdala) during anticipation of painful, heat stimuli compared with healthy subjects.

• Furthermore in MDD subjects, greater activation of the amygdala was associated with greater levels of perceived helplessness.

• This implies anticipation of pain may further pain experience and activation of the pain matrix potentially contributing to persistence of pain.

• In other studies the cingulate and PFC has also been implicated in pain modulation and may contribute to chronic pain associated with fibromyalgia syndrome[40].

The brain is perceived as a mediator for nociceptive pain, but also for pain behaviours which are known to influence pain itself, likely causing its persistence.

‘Central sensitisation syndrome’ (CSS) is a highly recognised symptom of chronic pain syndrome. Hyperaesthesia and allodynia (increased sensitivity to painful and non-painful stimuli) are features of CSS and have been suggested to be mediated by synaptic strengthening and neuroplastic change at multiple CNS levels[34] further strengthening the hypothesis of the brains role in nociceptive changes in the peripheries.

• The authors of this article[34] proposed that anxiety and depression may have similar physiological effects on programming in the brain providing more evidence for the relationship.

It is clear from research studies that physiology of depression, anxiety and pain is overlapping. However it is difficult to establish which the primary cause is and which is secondary.

Research, as discussed, demonstrates that psychiatric impairment can contribute to persistence of pain in a number of conditions, but also that in TMsI, for example, that incidence of psychiatric disorders is increased post injury[29][30].

Add text here...

Pain and catastrophizing.

- What is Catastrophizing?

Pain catastrophizing refers to a negative cognitive-affective response to anticipated or actual pain [46] . It was formally introduced by Albert Ellis and was used to describe a mal-adaptive cognitive style in those with anxiety and depressive disorders [47]. The research focussed on the fact that catastrophizing was an exaggerated and negative cognitive and emotional response during an actual or anticipated painful stimulation. Catastrophizing is often characterised by people magnifying their feelings about painful situations and ruminating about them which can combine with feelings of helplessness [48]. Catastrophizing plays an important role in models of pain chronicity, showing a high correlation with both pain intensity and disability [49]. However, it is also apparent that fear avoidance and depression are important predictors of pain intensity and disability [50]. High correlations between fear avoidance and pain catastrophizing have been found [51], however only pain catastrophizing predicted pain intensity [51]. Additionally, catastrophizing has also been linked to adverse pain outcomes [52] [53] [48]and it can therefore be surmised that a reduction in pain catastrophizing will lead to a reduction in pain and disability [54]. This highlights the importance of a multifactorial approach to pain management and the significance catastrophizing has in moulding the pain experience.

How can we assess the levels of catastrophizing?

Research has developed self-report instruments that can be used in various populations [51].Most commonly used is a 3 factor hierarchical structure for pain catastrophizing called The Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS) Figure 1. This incorporates magnification, rumination and helplessness. Highlighting the need for a multifactorial approach, participants are asked to rate the extent to which they experience each item by recalling previous experiences with pain [46]. The more negative experiences with pain can correlate with higher levels or pain intensity and disability [49].

Figure 1

- Why does this happen?

There are various theoretical mechanisms of action including the appraisal theory [55] where the levels of helplessness the person is feeling will affect their ability to cope. Attention bias/information processing [56] where the catastrophizing amplifies the experience of pain via amplified attention biases to sensory and affective pain information [56] and an inability to suppress pain related cognitions [46]. Evidence has also suggested that there is an increased nociceptive transmission via spinal gating mechanisms and a central sensitisation of pain. This may represent a central nervous mechanism which is contributing to the development, maintenance and aggravation of persistent pain [46] [57] [58].

It is therefore apparent that both psychological and physiological factors play a huge part in the perception, maintenance, experience and management of pain and both directly influence each other. It is important to recognise these factors in both the acute and chronic pain patient in order to understand what aspects of their pain are a barrier to their recovery.

References[edit | edit source]

References will automatically be added here, see adding references tutorial.

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 Vlaeyen JWS and Linton SJ. Fear –avoidance and its consequences in chronic musculoskeletal pain: a state of the art. Pain 2000; 85: 317-332

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Rainville J, Smeets RJEM, Bendix T, Tveito TH, Poiraudeau S, Indahl AJ. Fear-avoidance beliefs and pain avoidance in low back pain- translating research into clinical practice. The Spine Journal 2011; 11: 895-903

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Leeuw M, Goossens ME, Linton SJ, Crombez G, Boersma K, Vlaeyen JWS. The Fear-Avoidance Model of Musculoskeletal Pain: Current State of Scientific Evidence. Journal of Behavioural Medicine 2007; 30: 77-94

- ↑ Kori, S.H., Miller, R.P., &amp;amp;amp;amp;amp; Todd, D.D. Kinesophobia: A new view of chronic pain. Pain Management 1990; 3:35-43

- ↑ Lethem J, Slade PD, Troup JD, Bentley G. Outline of a fear-avoidance model of exaggerated pain perception. Behav Res Ther 1983; 21: 401-408

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedTurk and Okifuji - ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Pincus T, Vogel S, Burton AK, Santos R, Field A. Fear avoidance and prognosis in back pain. A systematic review and synthesis of current evidence. Arthritis and Rheumatism 2006; 54: 3999-4010

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 International Association for the Study of Pain. Pain Clinical Updates August 2007; 15

- ↑ Linton SJ. A Review of Psychological Risk Factors in Back and Neck pain. Spine 2000; 25: 1148-1156

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Boersma K, Linton SJ. How does persistent pain develop? An analysis of the relationship between psychological variables, pain and function across stages of chronicity. Behav Res Ther 2005; 43: 1495-1507

- ↑ Boersma K, Linton SJ. Expectancy, fear and pain in the prediction of chronic pain and disability: A prospective analysis. Europ J of Pain 2006; 10: 551-557

- ↑ Grotle M, Vollestad NK, Veierod MB, Brox JI. Fear-avoidance beliefs and distress in relation to disability in acute and chronic back pain. Pain 2004; 112: 343-352.

- ↑ Picavet HS, Vlaeyen JWS, Schouten JS. Pain catastrophizing and kinesophobia: predictors of chronic back pain. Am J Epidemiol 2002; 156: 1028-1034

- ↑ Woby S, Watson P, Roach N, Urmston M. Are changes in fear-avoidance beliefs, catastrophizing and appraisals of control, predictive of changes in chronic low back pain and disability? European Journal of Pain 2004; 8: 201-210

- ↑ Linton SJ, Buer N, Vlaeyen JWS, Hellsing, AL. Are fear –avoidance beliefs related to the inception of an episode of back pain? A prospective study. Psychol Helath 1999; 14: 1051-1059

- ↑ Klenerman ChM, Slade PD, Stanley IM, Pennie B, Reilly JP, Atchinsn LE, Troup JDG, Rose MJ. The Prediction of chronicity in patients with an acute attack of low back pain in a general practice setting. Spine 20; 4: 478-484

- ↑ Fritz JM, George SZ, Delitto A. The role of fear-avoidance beliefs in acute low back pain: relationships with current and future disability work status. Pain 2001; 94: 7-15

- ↑ Swinkels-Meewise IE, Roelofs J, Verbeek AL, Oostendorp RA, Vlaeyen JWS. Fear of movement/(re)injury, disability and participation in acute low back pain. Pain 2003; 105: 371-379

- ↑ Swinkels-Meewise IE, Roelofs J, Oostendorp RA, Verbeek AL, Vlaeyen JWS. Acute low back pain: pain-related fear and catastrophizing influence physical performance and perceived disability. Pain 2006; 120: 36-43

- ↑ Sieben JM, Portegijs PJM, Vlaeyen JWS, Knottnerus JA. Pain related fear at the start of a new low back pain episode. European J Pain 2005; 9: 635-641

- ↑ Fordyce WE, Shelton JL, Dundore DE. The modification of avoidance learning in pain behaviors. J Behav Med 1982; 5: 405-414

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 22.4 22.5 22.6 Valente MA, Ribeiro José, Jensen MP. Coping, Depression, Anxiety, Self-Efficacy and Social Support: Impact on Adjustment to Chronic Pain. Escritos de Psycologia; Vol 2 No.3 (2009): 8-17

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 Tekur P, Chatametcha S, Hankey A, Negandra HR and Nagaranthna R. A comprehensive yoga programs improves pain, anxiety and depression in chronic low back pain patients more than exercise: An RCT. Complementary Medicines Therapy; Vol 20 Issue 3 (2012): 107-118

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 Castro MMC and Daltro C. Sleep patterns and symptoms of anxiety and depression in patients with chronic pain. Arquivos de Neuropsiquiatria 67, 1 (2009): 25-28

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 25.3 25.4 25.5 25.6 Castro MMC, Quarantini LC, Daltro C, Pires-Caldas M, Koenan KC, Kraychete DC and de Oliveira I. Comorbid depression and anxiety symptoms in chronic pain patients and their impact on health-related quality of life. Revista de Psyquiatria Clinica; 38, 4 (2011): 126-129

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 26.3 26.4 26.5 Bair MJ, Poleshuck EL, Wu J, Krebs EK, Damush TM, Tu W and Kroenke K. Clinical Journal of Pain; 29, 2 (2013): 95-101

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 Bair MJ, Wu J, Damush TM, Sutherland JM and Kroenke K. Association of Depression and Anxiety Alone and in Combination with Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain in Primary Care Patients. Psychosomatic Medicine; 70, 8 (2008): 890-897

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 28.3 28.4 28.5 Bener A, Verjee M, Defeeah EE, Falah O, Al-Jushaishi T, Schlogl J, Sedeeq A and Khan S. Psychological factors: anxiety, depression, and somatization symptoms in low back pain patients. Journal of Pain Research; 6 (2013): 95-101

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 Rosenbloom BN, Khan S, McCartney C and Katz J. Systematic review of persistent pain and psychological outcomes following traumatic musculoskeletal injury. Journal of Pain Research; 6 (2013): 39-51

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 30.3 Castillo RC, Wegener ST, Heins SE, Haythornthwaite JA, MacKenzie EJ and Bosse MJ. Longitudinal relationships between anxiety, depression, and pain: Results from a two-year cohort study of lower extremity trauma patients. Pain; 154, 12 (2013): 2860-2866

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 Potter MQ, Wylie JD, Greis PE, Burks RT and Tashjian RZ. Psychological Distress Negatively Affects Self-assessment of Shoulder Function in Patients With Rotator Cuff Tears. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research; 472, 12 (2014): 3926-3932

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Kazemi H, Ghassemi S, Fereshtehnejad SM, Amini A, Kolivand PH and Doroudi T. Anxiety and Depression in Patients with Amputated Limbs Suffering from Phantom Pain: A Comparative Study with Non-Phantom Chronic Pain. International Journal of Preventative Medicine; 4, 2 (2013): 218-225

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 33.3 Ahn SG, Kim SH, Chung KI, Park KS, Cho SY and Kim HW. Depression, Anxiety, Stress Perception, and Coping Strategies in Korean Military Patients with Chronic Prostatitis/Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome. Korean Journal of Urology; 53, 9 (2012): 643-648

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 34.3 34.4 Jain R, Jain S, Raison CL and Maletic V, “Painful diabetic neuropathy is more than pain alone: examining the role of anxiety and depression as mediators and complicators”, Current Diabetes Reports; 11, 4 (2011): 275-284

- ↑ Reme SE, Lie SA and Eriksen HR. Are 2 Questions Enough to Screen for Depression and Anxiety in Patients With Chronic Low Back Pain? Spine journal 39; 7 (2014) 455-462, doi:10.1097/BRS.0000000000000214, Accessed 06/11/14.

- ↑ Akkaya N, Atalay NŞ, Konukcu S and Şahin F. Effect of Number of Physical Therapy Sessions on Level of Pain, Depression, Anxiety, and Quality of Life. Journal Physical Medicine &amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp; Rehabilitation; 16 (2013): 8-13

- ↑ Phyomaung PP, Dubowitz J, Cicuttini FM, Fernando S, Wluka AE, Raaijmaakers P, Wang Y and Urquhart D. Are depression, anxiety and poor mental health risk factors for knee pain? A systematic review. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders; 15, 10 (2014), doi:10.1186/1471-2474-15-10, Accessed 01/11/14.

- ↑ Tripp DA, Nickel JC and Katz L. A feasibility trial of a cognitive-behavioural symptom management program for chronic pelvic pain for men with refractory chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Canadian Urological Association Journal; 5, 5 (2011), doi:10.5489/cuaj.10201, Accessed 05/11/14

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 McBeth J, McFarlane GJ, Hunt IM and Silman AJ. Risk factors for persistent chronic widespread pain: a community‐based study. Rheumatology; 40 (2001), doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/40.1.95, Accessed 10/11/14. fckLR[20] Dunne FJ and Dunne CA. Fibromyalgia, psychiatric co-morbidity, and the somato-sensory cortex. British Journal of Medical Practitioners; 5, 2 (2012): 522-525fckLR[

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 40.2 Dunne FJ and Dunne CA. Fibromyalgia, psychiatric co-morbidity, and the somato-sensory cortex. British Journal of Medical Practitioners; 5, 2 (2012): 522-525

- ↑ Vachon-Presseau E, Roy M, Martel M, Caron E, Marin M, Chen J, Albouy G, Plante I, Sullivan MJ, Lupien SJ and Rainville P. The stress model of chronic pain: evidence from basal cortisol and hippocampal structure and function in humans. Brain Journal; 136 (2013), DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/brain/aws371. Accessed 10/11/14. fckLR[

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 42.2 Goldin PR and Gross JJ. Effects of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) on Emotion Regulation in Social Anxiety Disorder. Emotion; 10, 1 (2010): 83-91

- ↑ Porro CA. Functional imaging and pain: behavior, perception, and modulation. Neuroscientist; 9, 5 (2003): 354-369

- ↑ Bär K, Wagner G, Koschke M, Boettger S, Boettger MK, Schlösser R and Sauer H. Increased prefrontal activation during pain perception in major depression. Biological Psychiatry; 62, 11 (2007): 1281-1287

- ↑ Strigo IA, Simmons AN, Matthews SC, Craig AD and Paulus MP. Major depressive disorder is associated with altered functional brain response during anticipation and processing of heat pain. Archives of General Psychiatry; 65, 11 (2008): 1275-1284

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 46.2 46.3 Quartana PJ, Campbell CM, and Edwards RR. Pain Catastrophizing: a Critical Review. Expert Review of Neuropathics, May 2009; 9 (5): 745-758

- ↑ Ellis A. Reason and Emotion in Psychotherapy. Lyle Stewart; NY, USA: 1962

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 Sullivan MJ, Rodgers WM, Kirsh I. Catastrophizing, depression and expectancies for pain and emotional distress. Pain, 2001; 91: 147-154 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "Sullivan et al 2001" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ 49.0 49.1 Meyer K, Tschopp A, Sprott H, Mannion AF. Association between catastrophizing and self-rated pain and disability in patients with chronic low back pain. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine 2009; 41: 620-625

- ↑ Vlaeyen JW, Linton SJ. Fear avoidance and its consequences in chronic musculoskeletal pain: a state of the art. Pain 2000; 85: 317-332

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 51.2 George SZ, Dannecker EA, Robinson ME. Fear of pain, not pain catastrophizing, predicts acute pain intensity, but neither factor predicts tolerance or blood pressure reactivity: an experimental investigation in pain free individuals. European Journal of Pain 2006 July; 10 (5): 457-465

- ↑ Sullivan MJL, Bishop SR, Pivik J. The Pain Catastrophizing Scale: development and validation. Pshycol Assess 1995; 7 (4): 524-532

- ↑ Keefe FJ, Rumble ME, Scipio CD, Giordano LA, Perri LM. Measures of clinical pain severity, disability and depression. Journal of Pain 2004 May; 5 (4): 195-211

- ↑ Sullivan MJL, Lynch ME, Clark AJ. Dimensions of catastrophic thinking associated with pain experience and disability in patients with neuropathic pain conditions. Pain 2005; 113: 310-315

- ↑ Lazarus R, Folkman S. Stress, Apprisal and Coping. Springer; NY, USA: 1984

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 Eccleston C, Crombez G. Review: Pain demands attention. A Cognitive-affective model of the interruptive function of pain. Psychology Bulletin 1999 May; 125 (3): 356-366

- ↑ Weissman-Fogel I, Sprecher E, Pud D. Effects of catastrophizing on pain perception and pain modulation. Exp. Brain. Res. 2008 March; 186 (1): 79-85

- ↑ Sullivan MJL, Rodgers WM, Wilson PM, Bell GJ, Murray TC, Fraser SN. An experimental investigation of the relation between catastrophizing and activity intolerance. Pain 2002; 100: 47-53