Psychological Basis of Pain

- Please do not edit unless you are involved in this project, but please come back in the near future to check out new information!!

- If you would like to get involved in this project and earn accreditation for your contributions, please get in touch!

Tips for writing this page:

- Describe and explain current theories of the psychological basis of pain for example: fear avoidance, pain-related anxiety, pain catastrophising, stress and learned helplessness

- How might these impact upon a pain experince?

- If you feel some of these points shoudl be an article of thier own, which you woudl like to write, please get in touch!

Original Editor - Add a link to your Physiopedia profile here.

Top Contributors - Sharine Balicanta, Richard Benes, Kim Jackson, Jo Etherton, Shaimaa Eldib, Tarina van der Stockt, Simisola Ajeyalemi, Lauren Lopez, Admin, Luciana Segantin Lopes, Jess Bell, 127.0.0.1, Rachael Lowe, Evan Thomas, George Prudden and Kai A. Sigel

Introduction[edit | edit source]

The IASP definition of pain highlights the multidimensional complexity of the painful experience. The unpleasant feelings of pain and the negative emotions it evoke are part of the painful sensation [1]. Furthermore, the painful experience is interpreted by the individual based on its meaning and the threat it poses[2][3] . Each individual’s belief system and knowledge about the pain (i.e. pain signals damage and activity causes more harm) and emotions (anxiety, depression, catastrophizing) may influence its interpretation and affect subsequent behaviour (i.e. avoidance)[3]. To be able to understand and treat pain, one therefore must be able to understand how and why psychological factors impact on the experience of pain. Fear avoidance, catastrophizing, pain-related anxiety, stress and learned helplessness are some of the psychological factors implicated in the perception of pain.

Fear avoidance

Fear-avoidance refers to the” avoidance of movements or activities based on pain-related fear”[4]. Fear is the emotional response to experiences that are threatening, like a dangerous injury or painful experience [5][6]. Fear avoidance has been theorised as a factor that can maintain the painful experience despite the absence of physiological damage [7].

Fear avoidance in an acute injury, a normal response?

In acute injury or acute painful experience, intrinsic levels of fear may elevate as fear is a natural consequence of pain [3]. The individual may rest and protect the painful area as an adaptive behaviour which may be helpful during this acute stage when healing of injured tissues needs to happen [3] As the acute level of pain reduces, it has been suggested that individuals who confront their fears are able to resume normal activities and extinguish their fears [5]. For those whose fear avoidance response persists, it has been proposed that a cycle of continued avoidance of activities, aggravation of fear avoidance behaviors and disability ensues[4].

How does fear avoidance persist?

The following models proposed to explain how fear avoidance persists for some people.

In the fear-avoidance model of pain [4], the individuals who catastrophically interpret the painful experience will be:

• more fearful of pain

• more attentive to possible signals of threat (hypervigilance)

• likely to misinterpret normal somatic sensations as pathological (somatisation).

Due to hypervigilance, the avoidance behaviour begins to occur in anticipation rather than in response to pain [4][6] With fewer and fewer opportunities to correct the wrongful association of pain with the avoided activity, the behaviour perpetuates itself and fear avoidance persists [4]. In this model, catastrophizing is a prerequisite to the development of fear avoidance behaviour [8]. If this model is to be followed, it would be helpful to screen for high levels of fear avoidance and catastrophizing in the early stages of an acute injury to determine those at risk for the fear avoidance behaviour to persist.

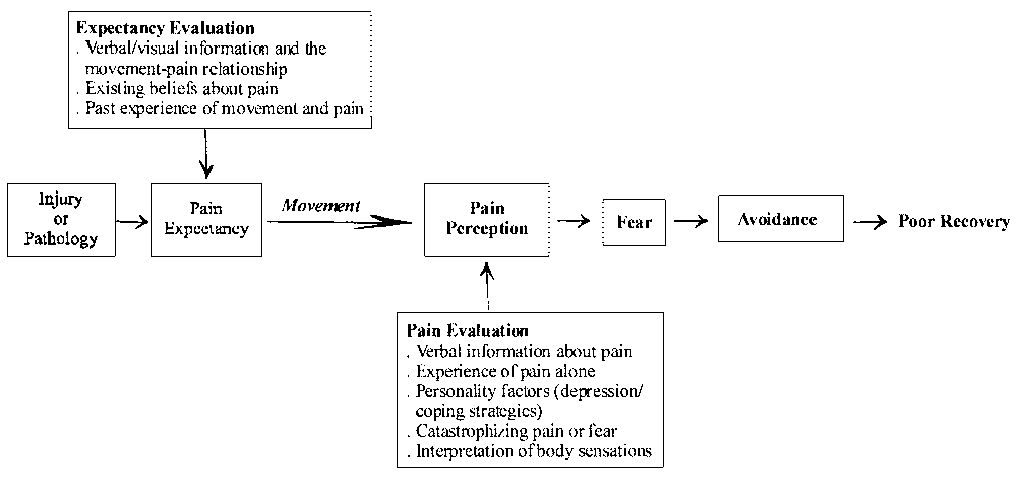

In the learning model, fear avoidance becomes a conditioned response through association of pain with movement [4][5][8]. The behaviour of avoiding expected pain-provoking movement or activities to prevent new episodes of pain is learned through experience [9]. The individual may anticipate similar experiences and associate non-painful or nonharmful experiences with pain [5] resulting in persistent fear avoidance behavior.

In this model, factors like existing beliefs about pain, prior learning experiences, observations of painful experiences, expectations and current emotional states (which include catastrophizing, anxiety, depression) can affect the strength of association of pain with movement and the conditioned fear avoidance response [8]. This model can support classification of fear-avoiders[5] to

• misinformed avoiders who have misinformed beliefs about movement and risk for damage or re-injury; may benefit from right information about pain and movement

• learned avoiders who learned the behaviour without being aware nor overly distressed about it; may benefit from gradual exposure to activity depending on pain tolerance

• affective avoiders who are distressed and have strong negative cognitions about the pain; may need more cognition-based management and challenge beliefs

How does fear avoidance maintain pain in chronic pain?

Where fear avoidance may serve a protective function in the acute phase of injury, persistent reliance on fear avoidance to cope with persistent pain could be considered maladaptive, and a potential barrier to recovery [3]. The following mechanisms have been cited [3][4][6][10] by which fear avoidance can maintain the pain experience in patients with chronic pain

• increased physiological arousal

• associated anxiety and hypervigilance leads to increased attention to expected painful stimulus which in itself can intensify the pain

• Persistent avoidance becomes self-perpetuating due to lack of opportunities to correct the wrongful association of pain with movement; promoting disability and disuse; disuse can further worsen the pain problem

Sub Heading 3

Add text here...

References[edit | edit source]

References will automatically be added here, see adding references tutorial.

- ↑ Price D. Central neural mechanisms that interrelated sensory and affective dimensions of pain. Molecular Interventions 2002; 2: 392-402

- ↑ Moseley GL. A pain neuromatrix approach to patients with chronic pain. Manual Therapy 2003 doi:10.1016/S1356-689X(03)00051-1

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 Turk D, Okifugi A. Psychological Factors in chronic pain: evolution and revolution. J of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 2002; 70: 678-690

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 Vlaeyen JWS and Linton SJ. Fear –avoidance and its consequences in chronic musculoskeletal pain: a state of the art. Pain 2000; 85: 317-332

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Rainville J, Smeets RJEM, Bendix T, Tveito TH, Poiraudeau S, Indahl AJ. Fear-avoidance beliefs and pain avoidance in low back pain- translating research into clinical practice. The Spine Journal 2011; 11: 895-903

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Leeuw M, Goossens ME, Linton SJ, Crombez G, Boersma K, Vlaeyen JWS. The Fear-Avoidance Model of Musculoskeletal Pain: Current State of Scientific Evidence. Journal of Behavioural Medicine 2007; 30: 77-94

- ↑ Lethem J, Slade PD, Troup JD, Bentley G. Outline of a fear-avoidance model of exaggerated pain perception. Behav Res Ther 1983; 21: 401-408

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Pincus T, Vogel S, Burton AK, Santos R, Field A. Fear avoidance and prognosis in back pain. A systematic review and synthesis of current evidence. Arthritis and Rheumatism 2006; 54: 3999-4010

- ↑ Fordyce WE, Shelton JL, Dundore DE. The modification of avoidance learning in pain behaviors. J Behav Med 1982; 5: 405-414

- ↑ Houben RMA, Leeuw M, Vlaeyen JWS, Goubert L, Picavet HSJ. Fear of movement/injury in the general population: Factor structure and psychometric properties of an adapted version of the Tampa Scale for Kinesophobia. J B Med 2005; 28: 415-424