Psychological Basis of Pain: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 15: | Line 15: | ||

== Introduction == | == Introduction == | ||

The IASP definition of pain highlights the multidimensional complexity of the painful experience. The unpleasant feelings of pain and the negative emotions it evoke are part of the painful sensation <ref name="Price">Price D. Central neural mechanisms that interrelated sensory and affective dimensions of pain. Molecular Interventions 2002; 2: 392-402</ref>. The painful experience is interpreted by the individual based on its meaning and the threat it poses<ref name="Moseley">Moseley GL. A pain neuromatrix approach to patients with chronic pain. Manual Therapy 2003 doi:10.1016/S1356-689X(03)00051-1</ref><ref name="Turk and Okifuji">Turk D, Okifuji A. Psychological Factors in chronic pain: evolution and revolution. J of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 2002; 70: 678-690</ref> . Each individual’s belief system and knowledge about the pain (i.e. pain signals damage and activity causes more harm) and emotions (anxiety, depression, catastrophizing) may influence its interpretation and affect subsequent behaviour (i.e. avoidance)<ref name=" | The IASP definition of pain highlights the multidimensional complexity of the painful experience. The unpleasant feelings of pain and the negative emotions it evoke are part of the painful sensation <ref name="Price">Price D. Central neural mechanisms that interrelated sensory and affective dimensions of pain. Molecular Interventions 2002; 2: 392-402</ref>. The painful experience is interpreted by the individual based on its meaning and the threat it poses<ref name="Moseley">Moseley GL. A pain neuromatrix approach to patients with chronic pain. Manual Therapy 2003 doi:10.1016/S1356-689X(03)00051-1</ref><ref name="Turk and Okifuji">Turk D, Okifuji A. Psychological Factors in chronic pain: evolution and revolution. J of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 2002; 70: 678-690</ref> . Each individual’s belief system and knowledge about the pain (i.e. pain signals damage and activity causes more harm) and emotions (anxiety, depression, catastrophizing) may influence its interpretation and affect subsequent behaviour (i.e. avoidance)<ref name="Vlaeyen and Linton">Vlaeyen JWS and Linton SJ. Fear –avoidance and its consequences in chronic musculoskeletal pain: a state of the art. Pain 2000; 85: 317-332</ref>. To be able to understand and treat pain, one therefore must be able to understand how and why psychological factors impact on the experience of pain. Fear avoidance, catastrophizing, pain-related anxiety, stress and learned helplessness are some of the psychological factors implicated in the perception of pain. | ||

<span style="font-size: 20px; line-height: 30px;">Fear avoidance</span> | <span style="font-size: 20px; line-height: 30px;">Fear avoidance</span> | ||

Fear-avoidance refers to the” avoidance of movements or activities based on pain-related fear”<ref name="Vlaeyen and Linton" | Fear-avoidance refers to the” avoidance of movements or activities based on pain-related fear”<ref name="Vlaeyen and Linton" />. Fear is the emotional response to experiences that are threatening, like a dangerous injury or painful experience <ref name="Rainville et al">Rainville J, Smeets RJEM, Bendix T, Tveito TH, Poiraudeau S, Indahl AJ. Fear-avoidance beliefs and pain avoidance in low back pain- translating research into clinical practice. The Spine Journal 2011; 11: 895-903</ref><ref name="Leeuw et al">Leeuw M, Goossens ME, Linton SJ, Crombez G, Boersma K, Vlaeyen JWS. The Fear-Avoidance Model of Musculoskeletal Pain: Current State of Scientific Evidence. Journal of Behavioural Medicine 2007; 30: 77-94</ref>. Avoidance is the behavioural response of patients with pain to fears of pain, work-related activities, movement, and re-injury <ref name="Leeuw et al" />. Fear avoidance has been theorised as a factor that can maintain the painful experience despite the absence of physiological damage <ref name="Lethem et al">Lethem J, Slade PD, Troup JD, Bentley G. Outline of a fear-avoidance model of exaggerated pain perception. Behav Res Ther 1983; 21: 401-408</ref>.<br> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

Revision as of 16:28, 24 November 2014

- Please do not edit unless you are involved in this project, but please come back in the near future to check out new information!!

- If you would like to get involved in this project and earn accreditation for your contributions, please get in touch!

Tips for writing this page:

- Describe and explain current theories of the psychological basis of pain for example: fear avoidance, pain-related anxiety, pain catastrophising, stress and learned helplessness

- How might these impact upon a pain experince?

- If you feel some of these points shoudl be an article of thier own, which you woudl like to write, please get in touch!

Original Editor - Add a link to your Physiopedia profile here.

Top Contributors - Sharine Balicanta, Richard Benes, Kim Jackson, Jo Etherton, Tarina van der Stockt, Shaimaa Eldib, Simisola Ajeyalemi, Lauren Lopez, Admin, George Prudden, Kai A. Sigel, Luciana Segantin Lopes, Jess Bell, 127.0.0.1, Rachael Lowe and Evan Thomas

Introduction[edit | edit source]

The IASP definition of pain highlights the multidimensional complexity of the painful experience. The unpleasant feelings of pain and the negative emotions it evoke are part of the painful sensation [1]. The painful experience is interpreted by the individual based on its meaning and the threat it poses[2][3] . Each individual’s belief system and knowledge about the pain (i.e. pain signals damage and activity causes more harm) and emotions (anxiety, depression, catastrophizing) may influence its interpretation and affect subsequent behaviour (i.e. avoidance)[4]. To be able to understand and treat pain, one therefore must be able to understand how and why psychological factors impact on the experience of pain. Fear avoidance, catastrophizing, pain-related anxiety, stress and learned helplessness are some of the psychological factors implicated in the perception of pain.

Fear avoidance

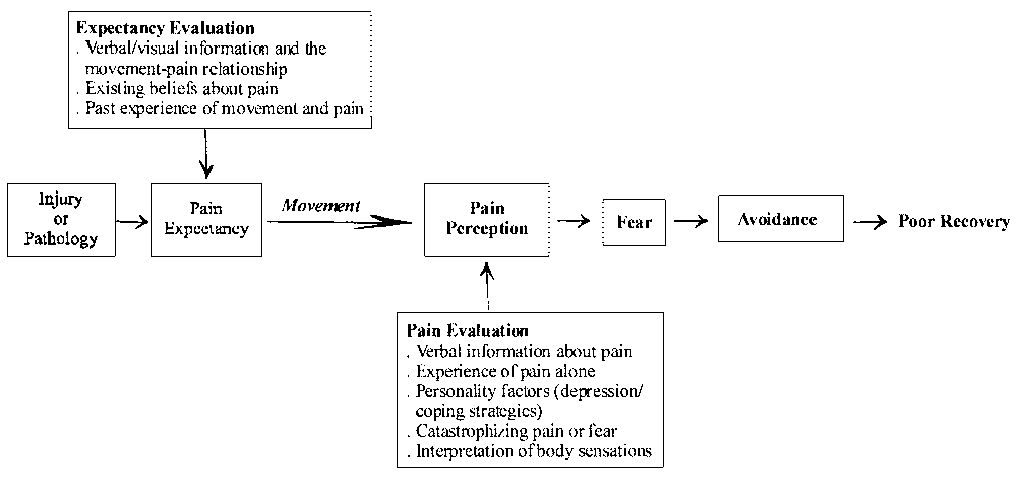

Fear-avoidance refers to the” avoidance of movements or activities based on pain-related fear”[4]. Fear is the emotional response to experiences that are threatening, like a dangerous injury or painful experience [5][6]. Avoidance is the behavioural response of patients with pain to fears of pain, work-related activities, movement, and re-injury [6]. Fear avoidance has been theorised as a factor that can maintain the painful experience despite the absence of physiological damage [7].

Fear avoidance in an acute injury, a normal response?

In acute injury or acute painful experience, intrinsic levels of fear may elevate as fear is a natural consequence of pain [8]. The individual may rest and protect the painful area as an adaptive behaviour which may be helpful during this acute stage when healing of injured tissues needs to happen [8] As the acute level of pain reduces, it has been suggested that individuals who confront their fears are able to resume normal activities and extinguish their fears [5]. For those whose fear avoidance response persists, it has been proposed that a cycle of continued avoidance of activities, aggravation of fear avoidance behaviors and disability ensues[4].

How does fear avoidance persist?

The following models proposed to explain how fear avoidance persists for some people, and how it impacts on pain, behaviour and disability. .

FEAR AVOIDANCE MODEL

In the fear-avoidance model of pain [4], the individuals who catastrophically interpret the painful experience will be:

• more fearful of pain

• more attentive to possible signals of threat (hypervigilance)

• likely to misinterpret normal somatic sensations as pathological (somatisation).

• have associated negative affectivity (the general tendency to experience subjective distress and dissatisfaction)

In this model, catastrophizing is a prerequisite to the development of fear avoidance behaviour [9]. With negative appraisals of the pain, fear avoidance behaviors are elicited [10]. Due to hypervigilance, the avoidance behaviour begins to occur in anticipation rather than in response to pain [4][6] As there are fewer and fewer opportunities to correct the wrongful association of pain with the avoided activity, the behaviour perpetuates itself and fear avoidance persists [4].

Fear avoidance and disability

The pathway to disability can be through the following means:

• Increased anticipation of pain leads to poorer performance of activities, which can be the pathway to disuse (6) and disability.

• Increased attention to pain has been reported to cause difficulty to focus on ongoing, non-painful tasks (9)

If this model is to be followed, it would be helpful to screen for high levels of fear avoidance and catastrophizing in the early stages of pain to determine those at risk for the fear avoidance behaviour to persist.

Fear avoidance model and chronic pain

This model has also been proposed primarily as mechanism for how pain is maintained in chronic low back pain. Where fear avoidance may serve a protective function in the acute phase of injury, persistent reliance on fear avoidance to cope with persistent pain could be considered maladaptive, and a potential barrier to recovery [3] .

The following mechanisms have been cited [3][4][6][10] by which fear avoidance can maintain the pain experience in patients with chronic pain

• increased physiological arousal/heightened muscle reactivity

• associated anxiety and hypervigilance leads to increased attention to expected painful stimulus which in itself can intensify the pain

• Persistent avoidance becomes self-perpetuating due to lack of opportunities to correct the wrongful association of pain with movement; promoting disability and disuse;disuse can further worsen the pain problem

• Reduced participation in valued activities like work, leisure and social contacts can lead to mood changes like irritability, frustration and depression. These mood changes could further affect perception of pain

• Disuse or disability from persistent avoidance behavior can reduce threshold for experiencing future pain

Research has shown an association of fear avoidance and pain related fears [11][12][13][14][15][16] even when pain intensity and other variables were controlled in patients with chronic pain. There is ongoing research aiming to prove the application of fear avoidance model on the acute stage of low back pain. Some researches showed that high levels of fear avoidance in this stage can be a predictor for future episodes of pain [17][18][19][20][21]. There are researches that has contrary results which can suggest that fear avoidance in the early stages of injury may not be may a path for future disability and pain.

THE LEARNING PATHWAY MODEL

In the learning model, fear avoidance becomes a conditioned response through association of pain with movement [4][5][9]. The behaviour of avoiding expected pain-provoking movement or activities to prevent new episodes of pain is learned through experience [22]. The individual may anticipate similar experiences and associate non-painful or nonharmful experiences with pain [5] resulting in persistent fear avoidance behavior.

In this model, factors like existing beliefs about pain, prior learning experiences, observations of painful experiences, expectations and current emotional states (which include catastrophizing, anxiety, depression) can affect the strength of association of pain with movement and the conditioned fear avoidance response [9]. This model can support classification of fear-avoiders[5] to

• misinformed avoiders who have misinformed beliefs about movement and risk for damage or re-injury; may benefit from right information about pain and movement

• learned avoiders who learned the behaviour without being aware nor overly distressed about it; may benefit from gradual exposure to activity depending on pain tolerance

• affective avoiders who are distressed and have strong negative cognitions about the pain; may need more cognition-based management and challenge beliefs

Sub Heading 3

Add text here...

References[edit | edit source]

References will automatically be added here, see adding references tutorial.

- ↑ Price D. Central neural mechanisms that interrelated sensory and affective dimensions of pain. Molecular Interventions 2002; 2: 392-402

- ↑ Moseley GL. A pain neuromatrix approach to patients with chronic pain. Manual Therapy 2003 doi:10.1016/S1356-689X(03)00051-1

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Turk D, Okifuji A. Psychological Factors in chronic pain: evolution and revolution. J of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 2002; 70: 678-690

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 Vlaeyen JWS and Linton SJ. Fear –avoidance and its consequences in chronic musculoskeletal pain: a state of the art. Pain 2000; 85: 317-332

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Rainville J, Smeets RJEM, Bendix T, Tveito TH, Poiraudeau S, Indahl AJ. Fear-avoidance beliefs and pain avoidance in low back pain- translating research into clinical practice. The Spine Journal 2011; 11: 895-903

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Leeuw M, Goossens ME, Linton SJ, Crombez G, Boersma K, Vlaeyen JWS. The Fear-Avoidance Model of Musculoskeletal Pain: Current State of Scientific Evidence. Journal of Behavioural Medicine 2007; 30: 77-94

- ↑ Lethem J, Slade PD, Troup JD, Bentley G. Outline of a fear-avoidance model of exaggerated pain perception. Behav Res Ther 1983; 21: 401-408

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedTurk and Okifugi - ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Pincus T, Vogel S, Burton AK, Santos R, Field A. Fear avoidance and prognosis in back pain. A systematic review and synthesis of current evidence. Arthritis and Rheumatism 2006; 54: 3999-4010

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 9. International Association for the Study of Pain. Pain Clinical Updates August 2007; 15

- ↑ Linton SJ. A Review of Psychological Risk Factors in Back and Neck pain. Spine 2000; 25: 1148-1156

- ↑ Boersma K, Linton SJ. How does persistent pain develop? An analysis of the relationship between psychological variables, pain and function across stages of chronicity. Behav Res Ther 2005; 43: 1495-1507

- ↑ Boersma K, Linton SJ. Expectancy, fear and pain in the prediction of chronic pain and disability: A prospective analysis. Europ J of Pain 2006; 10: 551-557

- ↑ Grotle M, Vollestad NK, Veierod MB, Brox JI. Fear-avoidance beliefs and distress in relation to disability in acute and chronic back pain. Pain 2004; 112: 343-352.

- ↑ Picavet HS, Vlaeyen JWS, Schouten JS. Pain catastrophizing and kinesophobia: predictors of chronic back pain. Am J Epidemiol 2002; 156: 1028-1034

- ↑ Woby S, Watson P, Roach N, Urmston M. Are changes in fear-avoidance beliefs, catastrophizing and appraisals of control, predictive of changes in chronic low back pain and disability? European Journal of Pain 2004; 8: 201-210

- ↑ Linton SJ, Buer N, Vlaeyen JWS, Hellsing, AL. Are fear –avoidance beliefs related to the inception of an episode of back pain? A prospective study. Psychol Helath 1999; 14: 1051-1059

- ↑ Klenerman ChM, Slade PD, Stanley IM, Pennie B, Reilly JP, Atchinsn LE, Troup JDG, Rose MJ. The Prediction of chronicity in patients with an acute attack of low back pain in a general practice setting. Spine 20; 4: 478-484

- ↑ Fritz JM, George SZ, Delitto A. The role of fear-avoidance beliefs in acute low back pain: relationships with current and future disability work status. Pain 2001; 94: 7-15

- ↑ Swinkels-Meewise IE, Roelofs J, Verbeek AL, Oostendorp RA, Vlaeyen JWS. Fear of movement/(re)injury, disability and participation in acute low back pain. Pain 2003; 105: 371-379

- ↑ Swinkels-Meewise IE, Roelofs J, Oostendorp RA, Verbeek AL, Vlaeyen JWS. Acute low back pain: pain-related fear and catastrophizing influence physical performance and perceived disability. Pain 2006; 120: 36-43

- ↑ Fordyce WE, Shelton JL, Dundore DE. The modification of avoidance learning in pain behaviors. J Behav Med 1982; 5: 405-414