Physical Activity in Individuals with Disabilities

Original Editor- Clara Hildt

Top Contributors - Ewa Jaraczewska, Tarina van der Stockt, Kim Jackson, Rachael Lowe, Lucinda hampton, Jess Bell, Mariam Hashem, Simisola Ajeyalemi, 127.0.0.1, Admin, Giulia Neculaes, Evan Thomas, George Prudden, Michelle Lee, WikiSysop, Rucha Gadgil, Aminat Abolade and Merinda Rodseth

Introduction[edit | edit source]

There are 1.2 billion persons with disabilities in the world. They represent 15% of the global population. In the United States, 20% of the population have a disability, which is 56 million US adults. [1] In Australia 1 in 6 people has a disability and profound or severe disability affects 1 in 3 people. [2]The World Bank estimates that one-fifth of the world population experience significant disability.[3]

There are many types of disabilities affecting a person’s movement, vision, hearing, thinking, remembering, learning, communication, mental health, and social relationship.[4]

Disability and Health[edit | edit source]

Sedentary behaviour that is often associated with disability, leads to deconditioning and health risk. The problem is so specific that is described as Disability-Associated Low Energy Expenditure Deconditioning Syndrome.[5]

Individuals with disabilities are 57% more likely to be obese than adults without disabilities. [6]Obesity is an important risk factor for adults with disability with a 33% higher chance of having a chronic condition eg.heart disease, diabetes, stroke or cancer. [7]

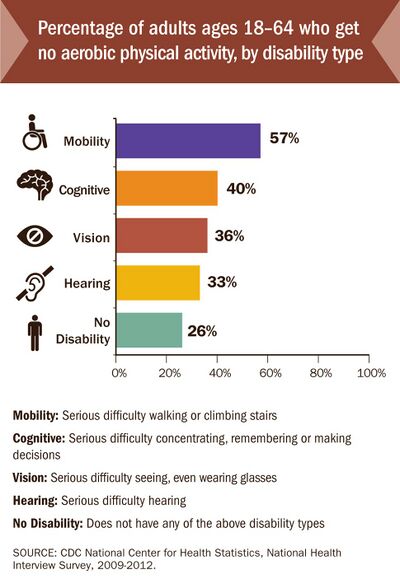

The impact of these chronic diseases can be reduced by aerobic physical activity but adults with disabilities only do physical activity on a regular basis about half as often as adults without disabilities (12% compared to 22%). [6][8]

Physical Activity[edit | edit source]

Definition[edit | edit source]

Physical Activity (PA) is defined as any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles that require energy expenditure.[9] Activities undertaken while working, playing, travelling, carrying out housework and engaging in recreational pursuits are included thereby. The WHO recommends for adults to do at least 150–300 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic physical activity throughout the week or at least 75–150 minutes of vigorous-intensity aerobic physical activity, or an equivalent combination of moderate- and vigorous-intensity activity throughout the week [10]. However, about 25% of the world's population remain insufficiently active, and this number is twice as high in high-income countries. [10]Compared to those who meet activity criteria, people who are insufficiently physically active have a 20% to 30% increased risk of all-cause mortality. [11]

Methods of measuring PA[edit | edit source]

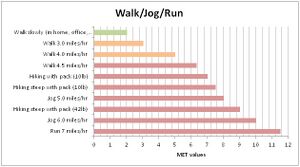

The level of physical activity can be measured in Metabolic Equivalent of Task (MET) defined as multiple of the resting metabolic rate. When considering individual characteristics, the threshold for the activity is based on relative intensities. Without taking a person's abilities into consideration, the absolute intensities become the reference threshold.[13]MET score of 1 defines the level of energy used by the person when resting. When physical activity guidelines use absolute intensities as a reference point, light activity is considered when METs is less than 3, while METs from 3.0 to 5.9 defines moderate activity. When METs is over 6, the activity is considered vigorous.

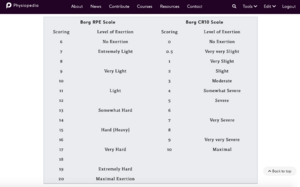

Another tool for measuring the level of physical activity is the Borg Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE). It is based on subjective, 6 to 20 scale and offers good estimate of the heart rate during performed activity.

Additional methods of measuring physical activities are:[14]

- self-report questionnaires

- self-report activities logs

- direct observation

- devices: accelerometers, pedometers, heart rate monitors, arm-band technology

Individuals with Disability[edit | edit source]

Disability does not define the person so when speaking about or working with individuals with a disability it is essential to put the person first. Positive language empowers and therefore inclusive language should always be used. [15][16]

"A disability is any condition of the body or mind (impairment) that makes it more difficult for the person with the condition to do certain activities (activity limitation) and interact with the world around them (participation restrictions)."[17]

In the medical model of disability the condition is viewed as a medical and biological difficulty. Correcting ill-being is highlighted instead of preventing ill-being and promoting well-being. On the contrary, in the social model disability is viewed as a difference and not judged. This model would emphasise barriers such as structural factors or discriminatory behaviours that prevent PA. Both the medical and social model are criticised for highlighting extreme point of views [18]. Out of it the social relational model was developed which suggests that both impairments as well as social and environmental barriers can all operate simultaneously [19]

Benefits of Physical Activity for Individuals with Disability[edit | edit source]

Physical activity is essential for quality of life reasons and as a public health promoter. [18]

In people with disabilities PA has an amplified importance based on higher rates of chronic diseases that PA can influence. Above those metabolic advantages individuals with disability can further profit from PA:

- Health benefit:

- PA has amplified importance for cognitive, emotional and social difficulties.

- Psychological benefits such as enhanced self-perception through successful PA experiences.

- PA can reduce stress, pain, and depression. Activities of Daily Living (ADLs) are perceived to be easier.

- Social contact:

- PA can reduce the stigmatisation process and negative stereotypes.

- PA can contribute to improve social status: non-disabled people see physically active individuals with disabilities more favourably than non-active people.

- Social benefits as the nature of many sport activities leads to increased social integration, bonding and friendship.

- Fun:

- PA leads to mood benefits.

- Enjoyment through social interaction of both fitness staff and other participants.

Barriers to Physical Activity[edit | edit source]

Despite the facilitators health benefits, social context and fun, there are depending on age and type of disability barriers on the individual, social and environmental level[21]:

Individual: lack of knowledge about where to exercise; lack of accessible knowledge/information about physical activity: what benefits there are to being active[22], how much activity should one do, and how safe is physical activity; fear of falling; the nature of the impairment producing pain during activity; lack of energy, lack of motivation, shame from being disabled;[8]personal concerns about safety; apprehension of attracting unwanted attention.

Social: children with disabilities dependancy on parents; ‘over-protective’ others (caregivers, spouses, family); Physical Education teachers lack professional preparation or equipment to work with students with disabilities; doctors providing medical excuses for students with disabilities to avoid Physical Education; no friends to play with for children with disabilities; inappropriate sports offer without suitable guidance; cost; limited social support; negative societal attitudes about disability from others (e.g. customers and staff of leisure centres).

Environmental: accessibility (too narrow gym doorways for wheelchair access, and inaccessible bathrooms or changing rooms); barriers in outdoor areas (e.g. poorly lit or wooded walking paths, traffic lights lack audible signals); [18] inadequate transportation; unsuitable equipment (e.g. no pool chair or arm cycles);[23]bad weather.

Health Care Provider[edit | edit source]

Guideline[edit | edit source]

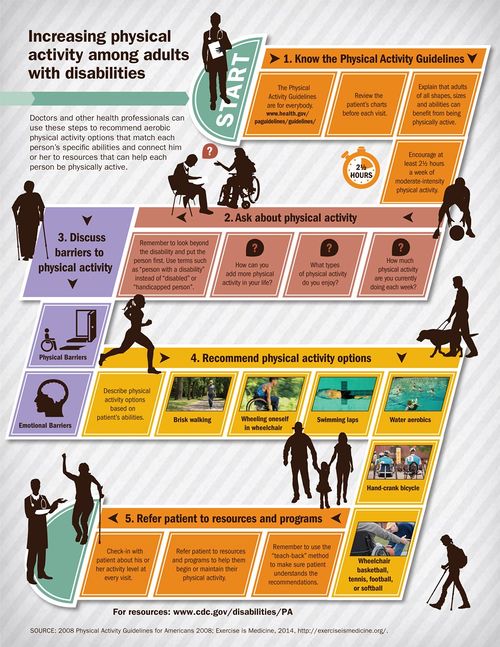

It is essential for physiotherapists and other health professionals to know the general Physical Activity Guidelines, as they are also applied for Individuals with disabilities. Adults with disabilities are more likely to be physically active if it is recommended by doctors. Thus if they got a PA recommendation they were 82% more likely to be physically active than those who did not get one. (CDC, 2014) [24] Physiotherapists and other health professionals can use these 5 steps as illustrated in the graphic below to increase physical activity among individuals with disabilities:

Interaction[edit | edit source]

General points you can consider when interacting with individuals with disabilities:

- If you are unsure about what to do when interacting with your patient, ask

- Speak directly to your patient instead of addressing a companion or interpreter when present

- Respect your patients’ assistive devices such as crutches or wheelchairs as their personal property that normally should not be moved unless having permission

- Consider extra time it may take your patient to transfer or prepare

- Never assume your patient needs your help. Offer your assistance and wait for reply and specific directions

- Avoid making general assumptions but instead try to get to know your patient’s individual needs, preferences and abilities.[16]

Find more specific advice here.

Promoting Physical Activity[edit | edit source]

Exercises[edit | edit source]

Find here factsheets describing various disabilities and health conditions, as well as physical activity, exercise, and overall health considerations and recommendations associated with each

Find here 5 easy general exercises for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities

Find [http://www.nchpad.org/1263/5964/Inclusive~Yoga NCHPAD Online program – “14 Weeks to a healthier You”: http://www.nchpad.org/14weeks/ here] different yoga poses

Inclusive Fitness Trainer[edit | edit source]

In the United States, an Inclusive Fitness Trainer (certified by the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) and the National Center on Health, Physical Activity and Disability (NCHPAD)), is a fitness professional who is uniquely qualified to work with people who have health risks and/or physical limitations. They have an understanding of the current Anti-Discrimination Act Policy and create adapted exercise programming that promotes safe and effective training. The aim is to empower individuals with disabilities to achieve their fitness goals.[25]

Campaign: How I Walk[edit | edit source]

“How I Walk is a movement to rebrand the word walking by challenging individual and societal perspectives.”[1] It is a call to action to promote walking and walkable communities. [1]

Special Olympics[edit | edit source]

Special Olympics is the world largest sports organisation for people with intellectual disabilities. There are programs in 169 countries with more than 4.7 million athletes and over a million volunteers. Through the joy of sport it aims to transform lives and to create a new world of inclusion. [26]

Visit this link for sports guides, rules and information

Sport Organisations[edit | edit source]

- International Wheelchair & Amputee Sports Federation

- International Paralympic Committee

- International Federation for Intellectual Disability Sport

- National Disability Sport Organisations in the UK.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 NCHPAD. How I Walk. About How I Walk. 2015 [cited 21/02/2017]. Available from: http://www.nchpad.org/howiwalk/

- ↑ Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. People with disabilities in Australia. Available at: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/disability/people-with-disability-in-australia/contents/people-with-disability/prevalence-of-disability. Accessed 14.11.2021

- ↑ The World Bank. Disability Inclusion. Available at: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/disability. Accessed 14.11.2021

- ↑ CDC Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Disability Overview. 2015 [cited 22/02/2017]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/disabilityandhealth/disability.html

- ↑ Rimmer JH, Schiller W, Chen MD. Effects of disability-associated low energy expenditure deconditioning syndrome. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2012 Jan;40(1):22-9.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 US Department of Health and Human Services. I can do it you can do it. 2017 [cited 22/02/2017]. Available from: https://www.fitness.gov/participate-in-programs/i-can-do-it-you-can-do-it/

- ↑ CDC Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Increasing Physical Activity among Adults with Disabilities. 2016 [cited 22/02/2017]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/disabilityandhealth/pa.html

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 de Hollander EL, Proper KI.Physical activity levels of adults with various physical disabilities.Preventive Medicine Reports 2018; 10:370-376

- ↑ Caspersen CJ, Powell KE, Christenson GM. Physical activity, exercise, and physical fitness: definitions and distinctions for health-related research. Public Health Rep. 1985 Mar-Apr;100(2):126-31.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 WHO. Physical Activity Fact sheet [Internet]. 2021. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs385/en/. Accessed 14.11.2021

- ↑ WHOa. Prevalence of insufficient physical activity [Internet]. 2017 [cited 23/02/2017]. Available from: http://www.who.int/gho/ncd/risk_factors/physical_activity_text/en/

- ↑ JPhysical Activity in Disabled Person. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kkPCPA5oUSg [last accessed 14/11/2021]

- ↑ Mendes MdA, da Silva I, Ramires V, Reichert F, Martins R, Ferreira R, et al. Metabolic equivalent of task (METs) thresholds as an indicator of physical activity intensity. 2018,PLoS ONE 13(7): e0200701.

- ↑ Sylvia LG, Bernstein EE, Hubbard JL, Keating L, Anderson EJ. Practical guide to measuring physical activity. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2014 Feb;114(2):199-208.

- ↑ Gov.uk. Inclusive language: words to use and avoid when writing about disability. 2014 [cited 23/02/2017]. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/inclusive-communication/inclusive-language-words-to-use-and-avoid-when-writing-about-disability

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 NCHPAD. fckLRfckLRDisability Awareness: Interaction Tips for the Fitness Professional. General Rules. 2017 [cited 21/02/2017]. Available from: http://www.nchpad.org/615/2567/Disability~Awareness~~Interaction~Tips~for~the~Fitness~Professional

- ↑ CDC Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Disability Overview. 2015 [cited 22/02/2017]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/disabilityandhealth/disability.html

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Martin JJ. Benefits and barriers to physical activity for individuals with disabilities: a social-relational model of disability perspective. Disability and Rehabilitation 2013; Researchgate

- ↑ Thomas C. How is disability understood? An examination of sociological approaches. Disabil Soc 2004;19:569–83.

- ↑ WeThe15. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gHCDvdCaJhI [last accessed 14/11/2021]

- ↑ Jaarsma EA, Dijkstra PU, Geertzen JHB, Dekker R. Barriers to and facilitators of sports participation for people with physical disabilities: A systematic review. 2014. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 24 (6), 871-881

- ↑ Wadey R, Melissa Day M. A longitudinal examination of leisure time physical activity following amputation in England.Psychology of Sport and Exercise 2018; 37: 251-261

- ↑ Smith B, Sparkes AC. Disability, sport, and physical activity. Routledge Handbook of Disability Studies (2nd edition) 2019. Routledge, London: 391-403.

- ↑ CDC Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Adults with Disabilities - Physical activity is for everybody. 2014 [cited 21/02/2017]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/disabilities/

- ↑ ACSM. ACSM/NCHPAD Certified Inclusive Fitness Trainer. 2015 [cited 21/02/2017]. Available from: http://certification.acsm.org/acsm-inclusive-fitness-trainer

- ↑ Special Olympics. What We Do. 2017 [cited 22/02/2017]. Available from: http://www.specialolympics.org/Sections/What_We_Do/What_We_Do.aspx