Patellar Tendinopathy

Original Editors - Dorien De Ganck

Top Contributors - George Prudden, Admin, Mathieu Henrotte, Dorien De Ganck, Kim Jackson, Derycker Andries, Chelsy De Bruyn, Vanessa Rhule, Rachael Lowe, Jess Bell, Yarne Leuckx, Wendy Walker, Evan Thomas, Tarina van der Stockt, WikiSysop, Simisola Ajeyalemi, Joris De Pot, Fee Waveryns, Alexandre Effinger, Wanda van Niekerk, Scott Buxton, Oyemi Sillo, Wendy Snyders, Naomi O'Reilly, Robin Tacchetti, Wajeeha Hassan, Mariam Hashem, 127.0.0.1 and Claire Knott

Topic Expert - Claire Robertson

Description[edit | edit source]

Patellar tendinopathy is a source of anterior knee pain, characterised by pain localised to the inferior pole of the patella. Pain is aggravated by loading and increased with the demand on the knee extensor musculature, notably in activities that store and release energy in the patellar tendon.

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

|

| Anatomy of the knee joint |

The quadriceps muscles are connected to the inferior pole of the patella by the common quadriceps tendon through the sesmoid bone, the patella. The patellar ligament then connects the bottom of the patella to the tibial tuberosity. The force generated from the quadriceps muscles acts through the patellar by acting as a pulley, causing the knee to extend[1]

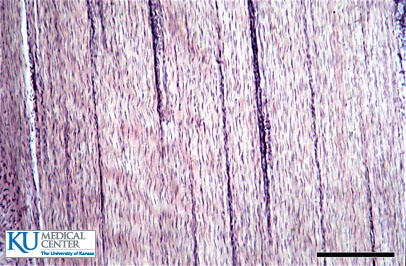

A healthy tendon is composed mostly of parallel collagen fibers closely packed together (86%)[2]. Collagen is predominantly type I. Other components of the tendon matrix are elastin (2%), proteoglycans (1–5%), and inorganic components (0.2%).

Pathological Process

[edit | edit source]

Causes [edit | edit source]

There is a higher prevalence noted in sports with high impact ballistic loading to the knee extensors. Microtrauma can occur when the patellar tendon is subjected to extreme forces such as rapid acceleration – decelaration, jumping, and landing. [3] Drastic changes in frequency and or intensity of training may also lead to overuse training errors. Intrinsic factors such as strength or flexibility may play a role. However the primary causes appear to relate to the extrinsic factors of overuse, improper training surfaces, insufficient foot-wear or inappropriate equipment. [4]

Physiological background[edit | edit source]

Patellar tendinopathy, also called Jumper’s knee, is a clinical condition of gradually progressive activity-related pain resulting from overuse of the knee.[5][6]It is a syndrome with micro tears and collagen degeneration in the patellar tendon also due to overuse but non- inflammatory .[7][8] The term tendinosis should be used as a histopathological and not a symptomatic description.[9][10] It affects both recreational and elite athletes who run and jump as p.e. in volleyball and basketball. Patellar tendinopathy occurs more frequently in those mature adolescents or adults, ranging from ages 16-40 years. [11][12]

Acute tendinitis involves an active inflammatory process, often occurring following an injury, which if treated, properly heals in 3-6 weeks.

Chronic patellar manifest itself after 6 weeks – 3months. These changes include absence of inflammatory cells in the tendon, a tendency toward poor healing, and decreased quality and disorganization of collagen fibers, both of which may lead to decreased tensile strength. Additonally, neovascularization, the growth of new vasculature in areas of poor blood supply, is common in chronic tendinopathy and may contribute to pain perception. The relationship between pain perception and neovasularization is not clearly understood, it is believed that increased levels of the neurotransmitter glutamate may play a role. [13] [14] [15]

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Pain is the first symptom of patellar tendinitis. The pain usually is located in the section of the patellar tendon . During physical activity, it may feel sharp especially when running or jumping. After the workout it will feel like a dull ache. There is swelling and tenderness in and around the patellar tendon. The knee will often feel ‘tight’ when moved towards flexion.[16][17][18]

The purpose of the evaluation is to differently diagnose between condition affecting the patella. We can use the Kennedy Scale to evaluate a chronic patellar tendinopathy [19] [20]:

- Phase 1: pain after activity

- Phase 2: pain at the beginning and after activity

- Phase 3: pain at the beginning, during and after activity, but the performance is not affected

- Phase 4: Pain at the beginning, during and after activity, and the performance is affected

Thickness of the tendon may be noted also in all stages. Pain in the patellar tendon may be reproduces with resisted knee extension.

The symptomatic evaluation should include history, age and any recent growth spurts, location of pain, and special tests.[21]

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

The signs and symptoms of patellar tendinitis are fairly easy to detect[22]. The athlete will complain of:

- pain in the area of the tendon,

- the knee will often feel "tight,"

- pain will be experienced early in the workout and after the workout is completed,

- there may be some subtle swelling of the tendon, and

- the athlete may feel that the tendon is "squeaking."

The key physical finding in patellar tendinopathy is tenderness at the inferior pole of the

patella or in the main body of the tendon when the knee is fully extended and the quadriceps relaxed. When the knee is flexed to 90 degrees, thus putting the tendon under tension, tenderness significantly decreases and often disappears altogether.

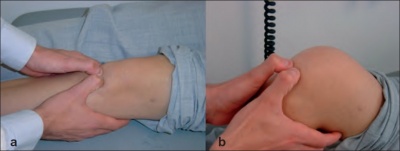

Two clinical signs can be performed to assess patellar tendinitis [23] .

In the “passive extension – flexion sign” the patient lies supine on the examination table. The anterior aspect of the extended knee is palpated to define the point of maximal tenderness.

In the case of patellar tendinitis, tenderness to palpation of the tendon is most often located at the origin of the tendon at the inferior pole of the patella. Once the point of maximal tenderness is identified, the knee is flexed to 90° and pressure is again applied to the tendon.

For the “standing active quadriceps sign”, the patellar tendon is palpated along its course while the patient stands. The point of maximal tenderness identified. The patient is then asked to stand only on the involved extremity with 30° of knee flexion and the tendon was re-palpated.

In both these tests, the patient should note a marked reduction of tenderness to palpation when the knee is flexed or the quadriceps contract, in order to confirm the diagnosis of patellar tendinitis.

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

- Pain provocation

- Tendon swelling

- Return to activity

Medical Management

[edit | edit source]

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

[edit | edit source]

The use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID’s) in the treatment of tendinopathy remains controversial both in the acute stage and in the chronic stage. NSAIDs have been reported to impede soft tissue healing. Although pain may be reduced, they have a negative effect on tendon repair[24]. In reactive tendinopathy, this may be a preferred effect, as this may inhibit proteins responsible for tendon swelling[25].

Corticosteroid injections

[edit | edit source]

Corticosteroid injections are a commonly administered treatment for tendon disorders. All the usual side-effects of corticosteroids are possible (such as skin atrophy, skin hypopigmentation, postinjection flare of symptoms, infection and possible effects from systemic absorption particularly after multiple injections). There is also the possible effect on the mechanical integrity of the

tendons themselves.

Surgical treatment

[edit | edit source]

Surgery for chronic painful tendons has produced varied outcomes, with 50–80% of athletes able to return to sport at their previous level[26]. Surgery in nonathletic people produced poorer results than in active people[27]. Surgery is considered a reasonable option in those who have failed all conservative interventions.

Physiotherapy Management

[edit | edit source]

Advice regarding selective rest should be provided to allow appropriate tendon healing following a period of acute overloading or unaccustomed exercise[28]. There should be a focus on an early return to activities.

Pain relief[edit | edit source]

Isometrics have been suggested as a possible analgesic exercise where isotonic exercises are not possible due to fatigue and high SIN. In a systematic review by Naugle et al.[29] isometric exercise has been found to be superior to aerobic and resistance exercises at reducing pain.

Rehabilitation[edit | edit source]

A variety of loading programs have been suggested for the treatment of patella tendinopathy with the main types being[30]:

- Eccentric loading

- Eccentric-concentric loading

| Program |

Exercise type |

Sets & reps |

Frequency |

Progression |

Pain |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alfredson |

Eccentric |

3x15 |

Twice daily |

Load |

Enough load to achieve up to moderate pain |

| Stanish and Curwin/Silbernagel |

Eccentric-concentric |

3x10-20 |

Daily |

Speed then load, type of exercise |

Enough load to be painful in third set |

| Heavy slow resistance training |

Eccentric-concentric |

4x6-15 |

3x/week |

6-15RM |

Acceptable if was not worse after |

Eccentric loading has been the most dominant approach for rehabilitation. Evidence suggests that loading is beneficial in reducing pain and returning function however eccentrics have lower patient subjective satisfaction. This is perhaps due to time commitment and pain required from eccentric programs. Gym machines such as leg press or knee extension provides control to the amount of loading.

Protocol[edit | edit source]

| Protocol as suggested by Malliaris et al. (2015)[31] | ||

| Stage |

Indication to initiate |

Dosage |

| 1. Isometric loading |

More than minimal pain during isometric exercise |

5 repetitions of 45 seconds, 2 to 3 times per day; progress to 70% maximal voluntary contraction as pain allows |

| 2. Isotonic loading |

Minimal pain during isotonic exercise |

3 to 4 sets at a load of 15RM, progressing to a load of 6RM, every second day; fatiguing load |

| 3. Energy-storing loading |

(A) Adequate strength and consistent with other side (B) Load tolerance with initial-level energy storage exercise (ie, minimal pain during exercise and pain on load tests returning to baseline within 24 h) |

Progressively develop volume and then intensity of relevant energy-storage exercise to replicate demands of sport |

| 4. Return to sport |

Load tolerance to energy-storage exercise progression that replicates demands of training |

Progressively add training drills, then competition, when tolerant to full training |

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

- Infrapatellar bursitis

- Fat pad impingement

- Patellofemoral pain

- Plica injuries

- Osgood-Schlatter syndrome

- Sinding-Larsen-Johansson syndrome

Key Evidence[edit | edit source]

- Isometric exercise induces analgesia and reduces inhibition in patellar tendinopathy. (Rio 2015)

- Patellar Tendinopathy: Clinical Diagnosis, Load Management, and Advice for Challenging Case Presentations. (Malliaris 2015)

- Physiotherapy management of patellar tendinopathy (jumper's knee). (Rudavsky 2014)

- Achilles and patellar tendinopathy loading programmes. (Malliaris 2013)

Resources[edit | edit source]

Case Studies[edit | edit source]

Recent Related Research (from Pubmed)[edit | edit source]

Failed to load RSS feed from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/erss.cgi?rss_guid=10AkQ1Iw49RKj2Dls_4vN-p0FB75-E6HcklAbWTJWvSBefDQfb|charset=UTF-8|short|max=10: Error parsing XML for RSS

References

[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Palastanga N, Field D, Soames R. Anatomy and human movement: structure and function. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2012.

- ↑ Lin TW, Cardenas L, Soslowsky LJ. Biomechanics of tendon injury and repair. Journal of biomechanics. 2004 Jun 30;37(6):865-77.

- ↑ Johannes Zwerver, Evert Verhagen, Fred Hartgens, Inge van den Akker-Scheek and Ron Diercks – The TOPGAME-study: effectiveness of extracorporeal shockwave therapy in jumping athlets with patellar tendionpaty: RCT (level of evidence: A1) – © Biomed Central 2010

- ↑ Witvrouw E, Bellemans J, Lysens, et al – Intrinsic risk factors for the development of patellar tendinits in an athletic population (LE: D)

- ↑ Torstensen, Eric T.; Bray, Robert C.; Wiley, J. Preston. Patellar Tendinitis: A Review of Current Concepts and Treatment. Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine. 1994 4(2):77-82, April.

- ↑ Johannes Zwerver, Evert Verhagen, Fred Hartgens, Inge van den Akker-Scheek and Ron Diercks – The TOPGAME-study: effectiveness of extracorporeal shockwave therapy in jumping athlets with patellar tendionpaty: RCT (level of evidence: A1) – © Biomed Central 2010

- ↑ Khan K, Cook J. The painful nonruptured tendon: clinical aspects. Clin Sports Med 2003;22:711-25.

- ↑ Almekinders LC, Temple JD. Etiology, diagnosis, and treatment of tendonitis: an analysis of the literature. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1998;30:1183-90.

- ↑ O'Connor FG, Howard TM, Fieseler CM, Nirschl RP. Managing overuse injuries: a systematic approach. Phys Sportsmed . 1997 May;25(5).

- ↑ Alfredson H., Pietila T., Johnston P., Lorentzon R. Heavy-load eccentric muscle training for the treatment of chronic Achilles tendinosis.Am J Sports Med 1998; 26 (3);360-366

- ↑ Ferretti A, Conteduca F, Camerucci E, Morelli F – A follow-up study of surgical treatment (LE: B)

- ↑ Khan Km, Maffulli N, Coleman BD, Cook JL, Taunton JE –Patellar tendinopathy: some aspects of basic science and clinical management (LE: D)

- ↑ Khan Km, Maffulli N, Coleman BD, Cook JL, Taunton JE –Patellar tendinopathy: some aspects of basic science and clinical management (LE: D)

- ↑ Maffulli N, Wong J, Almekinders LC – Types and epidemiology of tendionpathy (LE: D)

- ↑ Cook JL, Khan KM, Purdam CR – Conservative treatment of patellar tendiopathy (LE: C)

- ↑ Blazina ME, Kerlan RK, Jobe FW, Carter VS, Carlson GJ. Jumper’s knee. Orthop Clin North Am. 1973;4:665–78. [PubMed]

- ↑ Romeo AA, Larson RV. Arthroscopic treatment of infrapatellar tendonitis. Arthroscopy. 1999;15:341–5. [PubMed]

- ↑ Duri ZA, Aichroth PM, Wilkins R, Jones J. Patellar tendonitis and anterior knee pain. Am J Knee Surg. 1999 Spring;12(2):99-108.

- ↑ Johannes Zwerver, Evert Verhagen, Fred Hartgens, Inge van den Akker-Scheek and Ron Diercks – The TOPGAME-study: effectiveness of extracorporeal shockwave therapy in jumping athlets with patellar tendionpaty: RCT (level of evidence: A1) – © Biomed Central 2010

- ↑ Kennedy JC, Hawkins R, Krissoff WB – Orthopaedic manifestations of swimming (LE: D)

- ↑ Marsha Rutland, Dennis O’Connell, JM Brisméee, Gail Apte, Janelle O’Connell - Evidence-supported rehabilitation of patellar tendinopathy (LE: D)

- ↑ K M Khan, Patellar tendinopathy: some aspects of basic science and clinical management, fckLRBr J Sports Med, 1998 [A1]

- ↑ Ehud Rath et al., Clinical signs and anatomical correlation of patellar tendinitis, Indian Journal Orthopedy, 2010 [B]

- ↑ Ferry ST, Dahners LE, Afshari HM, Weinhold PS. The effects of common anti-inflammatory drugs on the healing rat patellar tendon. The American journal of sports medicine. 2007 Aug 1;35(8):1326-33.

- ↑ Riley GP, Cox M, Harrall RL, Clements S, Hazleman BL. Inhibition of tendon cell proliferation and matrix glycosaminoglycan synthesis by non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in vitro. Journal of Hand Surgery (British and European Volume). 2001 Jun 1;26(3):224-8.

- ↑ Tallon C, Coleman BD, Khan KM, Maffulli N. Outcome of surgery for chronic Achilles tendinopathy a critical review. The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 2001 May 1;29(3):315-20.

- ↑ Maffulli N, Testa V, Capasso G, Oliva F, Sullo A, Benazzo F, Regine R, King JB. Surgery for chronic Achilles tendinopathy yields worse results in nonathletic patients. Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine. 2006 Mar 1;16(2):123-8.

- ↑ Simpson M, Smith T. Quadriceps tendinopathy-a forgotten pathology for physiotherapists? A systematic review of the current evidence-base. Phys Ther Rev. 2011;16(6):455-61.

- ↑ Naugle KM, Fillingim RB, Riley JL. A meta-analytic review of the hypoalgesic effects of exercise. The Journal of pain. 2012;13(12):1139-50.

- ↑ Malliaras P, Barton CJ, Reeves ND, Langberg H. Achilles and patellar tendinopathy loading programmes. Sports Med. 2013;43(4):267-86.

- ↑ Malliaras P, Cook J, Purdam C, Rio E. Patellar Tendinopathy: Clinical Diagnosis, Load Management, and Advice for Challenging Case Presentations. The Journal of orthopaedic and sports physical therapy. 2015 Sep:1-33.