Pain Neuroscience Education (PNE): Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 29: | Line 29: | ||

# Increased pain response evoked by stimuli outside the area of injury, an expanded receptive field. | # Increased pain response evoked by stimuli outside the area of injury, an expanded receptive field. | ||

<br>Pre-existing factors (genetics) that may predispose an individual to have altered central nervous system functioning following injury<br>Factors (environmental) that may cause altered central nervous system functioning once injury has occurred. i.e. (anxiety, stress, depression, fear-avoidance and poor sleep)<br> | <br>Pre-existing factors (genetics) that may predispose an individual to have altered central nervous system functioning following injury<br>Factors (environmental) that may cause altered central nervous system functioning once injury has occurred. i.e. (anxiety, stress, depression, fear-avoidance and poor sleep)<br> | ||

Figure 5: Pain behaviours caused by central sensitisation | Figure 5: Pain behaviours caused by central sensitisation | ||

== | === Pain-Neuroscience Education Model === | ||

[[File:Upload_version_of_systemic_effects.jpg|alt=|thumb|500x500px|Pain behaviours caused by central sensitisation]] | |||

In the last century Descartes biomedical model has been replaced by the [http://www.physio-pedia.com/Biopsychosocial_Model biopsychosocial model] of [http://www.physio-pedia.com/Chronic_Pain chronic pain]<ref name=":12">Goldberg JS. Revisiting the Cartesian model of pain. Medical Hypotheses. 2008;70 (5):1029–1033.</ref>, in which pain is classified as being due to increased sensitivity of the nervous system rather than further injury.<ref name=":11">Linton SJ. Models of pain perception. Understanding Pain for Better Clinical Practice: A Psychological Perspective. Elsevier, 2005. p9-18.</ref> In layman’s terms, pain persists after tissue healing, due to the fact that the body’s alarm system remains activated, and are stimulated by a much lower intensity of stimulus<ref name=":5">Louw A. Therapeutic Neuroscience Education: Teaching People About Pain. 2014. Available from: http://www.instituteforchronicpain.org/treating-common-pain/what-is-pain-management/therapeutic-neuroscience-education. (accessed 6 Janurary 2016). </ref>; i.e. a much lower degree of movement provocation causes pain. | |||

People in pain are interested in pain and more specifically the mechanisms of pain.<ref>Louw A, Louw Q, Crous LC. Preoperative education for lumbar surgery for radiculopathy. South African Journal of Physiotherapy. 2009; 65(2):3-8.</ref> Current treatment for patients with chronic pain should have a greater focus on educating patients about the neuroscience of their pain, rather than classifying their pain as being due to faulty movement patterns or damaged tissues. | |||

==== Video of Alarm Systems ==== | ==== Video of Alarm Systems ==== | ||

| Line 86: | Line 64: | ||

== Indicators For the Use of PNE == | == Indicators For the Use of PNE == | ||

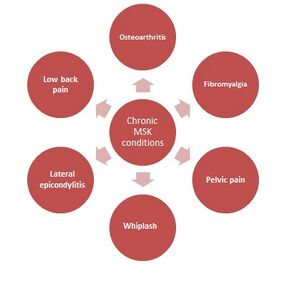

=== Chronic Musculoskeletal Conditions<ref name=":13" /> === | === Chronic Musculoskeletal Conditions<ref name=":13">Moseley GL, Butler DS. Fifteen years of explaining pain: the past, present, and future. The Journal of Pain. 2015;16(9):807-813.</ref> === | ||

[[Image:Chronic MSK conditions.jpg| | [[Image:Chronic MSK conditions.jpg|alt=|thumb|Chronic MSK conditions with positive PNE results ]]These conditions are often characterised by brain plasticity that leads to hyperexcitability of the central nervous system (central sensitisation). | ||

*PNE is recommended in<br>central sensitisation conditions like these,<br>as the patient may present with maladaptive<br>cognitions, behaviour, or coping<br>strategies in response to pain. | *PNE is recommended in<br>central sensitisation conditions like these,<br>as the patient may present with maladaptive<br>cognitions, behaviour, or coping<br>strategies in response to pain. | ||

| Line 94: | Line 72: | ||

*Evidence showing benefits for pre op MSK patients.<ref name=":6">Louw A, Diener I, Landers MR, Puentedura EJ. Preoperative pain neuroscience education for lumbar radiculopathy: a multicenter randomized controlled trial with 1-year follow-up. Spine. 2014; 39(18):1449-1457.</ref><ref name=":7">Zimney K, Louw A, Puentedura EJ. Use of Therapeutic Neuroscience Education to address psychosocial factors associated with acute low back pain: a case report. Physiotherapy theory and practice. 2014; 30(3):202-209.</ref> | *Evidence showing benefits for pre op MSK patients.<ref name=":6">Louw A, Diener I, Landers MR, Puentedura EJ. Preoperative pain neuroscience education for lumbar radiculopathy: a multicenter randomized controlled trial with 1-year follow-up. Spine. 2014; 39(18):1449-1457.</ref><ref name=":7">Zimney K, Louw A, Puentedura EJ. Use of Therapeutic Neuroscience Education to address psychosocial factors associated with acute low back pain: a case report. Physiotherapy theory and practice. 2014; 30(3):202-209.</ref> | ||

== References == | |||

== References | |||

<references /> | <references /> | ||

Revision as of 02:55, 19 April 2022

Original Editor - David Greaves, Lynette Fox, and Katie White as part of the Nottingham University Spinal Rehabilitation Project

Top Contributors - David Greaves, Lynette Fox, Becky Mead, Katie White, Kim Jackson, Maram Salem, Lucinda hampton, Uchechukwu Chukwuemeka, Vanessa Rhule, Rachael Lowe, Lauren Lopez, Rishika Babburu and Evan Thomas

Page Owner - Ina Diener as part of the One Page Project

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Pain neuroscience education (PNE) is a strategy that teaches patients to rethink the way they view pain. Pain neuroscience education utilises various stories and metaphors to help patients reconceptualise their pain experience.

Based on a large number of high-quality studies, it has been shown that teaching people with pain more about the neuroscience of their pain produces some impressive immediate and long-term changes. PNE has been shown to have positive effects in reducing pain, disability, and psychosocial problems, improving patient's knowledge of pain mechanisms, facilitating movement and decreasing healthcare consumption.[1]

Pain Neuroscience Education[edit | edit source]

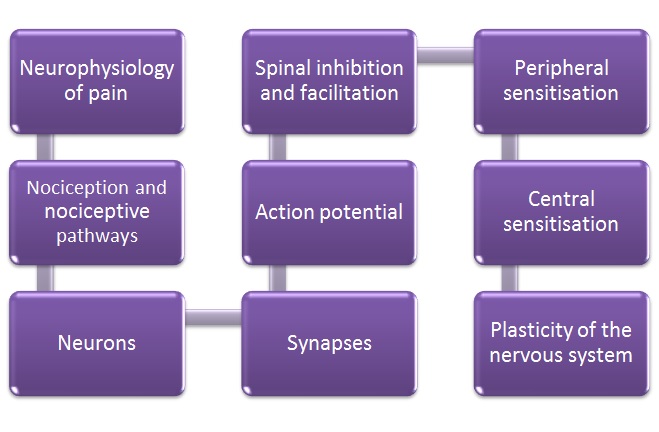

PNE consists of educational sessions for patients describing in detail the neurobiology and neurophysiology of pain and pain processing by the nervous system.[2]

This educational approach has been used by physiotherapists therapeutically since 2002 in various countries (eg UK, US, Australia) and differs considerably from traditional education strategies such as back school and biomechanical models.[3] Chronic pain in PNE is seen as not being caused not by unhealthy or dysfunctional tissues but brain plasticity leading to hyper-excitability of the central nervous system, known as central sensitisation.[4] Therefore, a deeper level reasoning and treatments beyond a medical model is required.

Initially, PNE changes a patient’s perception of pain.

- A patient may have believed that damaged tissues were the main cause for their pain, and by receiving education about pain neurophysiology the patient understands that pain may not correctly represent the health of the tissue, but may be due to extra-sensitive nerves. As a result, patients have been found to have a reduction in fear avoidance behaviours and are more able and willing to move.

PNE can be used with a combination of treatments, including exercise therapy that can be used to break down movement-related pain memories with graded exposure to exercise and decrease sensitivity of the nervous system.[4]

Central Sensitisation[edit | edit source]

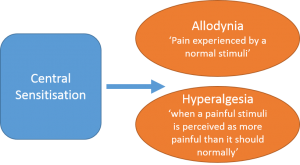

Central sensitisation is defined as an increased responsiveness of nociceptors in the central nervous system to either normal or sub-threshold afferent input resulting in:

- Hypersensitivity to stimuli.

- Responsiveness to non-noxious stimuli.

- Increased pain response evoked by stimuli outside the area of injury, an expanded receptive field.

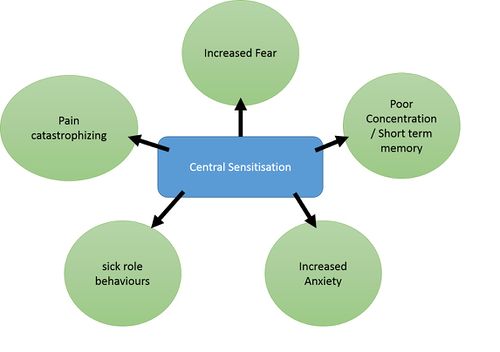

Pre-existing factors (genetics) that may predispose an individual to have altered central nervous system functioning following injury

Factors (environmental) that may cause altered central nervous system functioning once injury has occurred. i.e. (anxiety, stress, depression, fear-avoidance and poor sleep)

Figure 5: Pain behaviours caused by central sensitisation

Pain-Neuroscience Education Model[edit | edit source]

In the last century Descartes biomedical model has been replaced by the biopsychosocial model of chronic pain[5], in which pain is classified as being due to increased sensitivity of the nervous system rather than further injury.[6] In layman’s terms, pain persists after tissue healing, due to the fact that the body’s alarm system remains activated, and are stimulated by a much lower intensity of stimulus[7]; i.e. a much lower degree of movement provocation causes pain.

People in pain are interested in pain and more specifically the mechanisms of pain.[8] Current treatment for patients with chronic pain should have a greater focus on educating patients about the neuroscience of their pain, rather than classifying their pain as being due to faulty movement patterns or damaged tissues.

Video of Alarm Systems[edit | edit source]

What Does PNE Involve?[edit | edit source]

PNE first of all puts the complex process of describing the nerves and brain into a format that is easy to understand for everyone; no matter whether the target audience is of a particular age, educational level or ethnic group.[2]

This is made possible by using simplified scientific language used with additional methods of presenting information that may include the use of:

• Simple pictures

• Examples

• Booklets

• Metaphors

• Drawings

• Workbook with reading/question-answer assignments

• Neurophysiology Pain Questionnaires

Methods of PNE delivery vary but can typically involve around 4 hours of teaching that is provided to a group or individually, either in single or multiple sessions.[3]

Figure 6. showing the content of PNE education sessions with patients[2]

How is PNE Used in Clinical Practice?[edit | edit source]

A metaphor/story that can be found here: (http://www.instituteforchronicpain.org/treating-common-pain/what-is-pain-management/therapeutic-neuroscience-education) is used by Louw et al.[9] in clinical practice to teach patients about complex pain physiology including extra-sensitive nerves, inflammation, injury and how pain is created in the brain. It is such an example that helps patient to break away from a view of a particular tissue being the issue (e.g. generative disc) and helps the patient think towards the problem being related to pain and a sensitive nervous system.[9] Therefore, Instead of pain following spinal surgery being seen as the ‘problem has not resolved’ or ‘there is something still wrong with the disc’, PNE would explain pain is sensitive to act as a protector which is perfectly normal after surgery.

Video Interview of Low Back Pain From a Patient's Point of View[edit | edit source]

Indicators For the Use of PNE[edit | edit source]

Chronic Musculoskeletal Conditions[10][edit | edit source]

These conditions are often characterised by brain plasticity that leads to hyperexcitability of the central nervous system (central sensitisation).

- PNE is recommended in

central sensitisation conditions like these,

as the patient may present with maladaptive

cognitions, behaviour, or coping

strategies in response to pain. - Typically they acquire a protective (movement-related) pain memory, which causes a barrier to adhere to therapeutic treatment such as exercise, decreasing the likelihood of a good outcome.

- Therefore these maladaptive behaviours, central sensitisation and previous failed treatments are all indicators for PNE

- Evidence showing benefits for pre op MSK patients.[9][11]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Zimney KJ, Louw A, Cox T, Puentedura EJ, Diener I. Pain neuroscience education: Which pain neuroscience education metaphor worked best?. South African Journal of Physiotherapy. 2019 Jan 1;75(1):1-7. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6739553/(accessed 19.4.2022)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Louw A, Diener I, Butler DS, Puentedura EJ. The effect of neuroscience education on pain, disability, anxiety, and stress in chronic musculoskeletal pain. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 2011; 92(12):2041-2056.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Clarke CL, Ryan CG, Martin DJ. Pain neurophysiology education for the management of individuals with chronic low back pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Manual therapy. 2011; 16(6):544-549.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Nijs J, Girbés EL, Lundberg M, Malfliet A, Sterling M. Exercise therapy for chronic musculoskeletal pain: Innovation by altering pain memories. Manual therapy. 2015; 20 (1): 216-220.

- ↑ Goldberg JS. Revisiting the Cartesian model of pain. Medical Hypotheses. 2008;70 (5):1029–1033.

- ↑ Linton SJ. Models of pain perception. Understanding Pain for Better Clinical Practice: A Psychological Perspective. Elsevier, 2005. p9-18.

- ↑ Louw A. Therapeutic Neuroscience Education: Teaching People About Pain. 2014. Available from: http://www.instituteforchronicpain.org/treating-common-pain/what-is-pain-management/therapeutic-neuroscience-education. (accessed 6 Janurary 2016).

- ↑ Louw A, Louw Q, Crous LC. Preoperative education for lumbar surgery for radiculopathy. South African Journal of Physiotherapy. 2009; 65(2):3-8.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Louw A, Diener I, Landers MR, Puentedura EJ. Preoperative pain neuroscience education for lumbar radiculopathy: a multicenter randomized controlled trial with 1-year follow-up. Spine. 2014; 39(18):1449-1457.

- ↑ Moseley GL, Butler DS. Fifteen years of explaining pain: the past, present, and future. The Journal of Pain. 2015;16(9):807-813.

- ↑ Zimney K, Louw A, Puentedura EJ. Use of Therapeutic Neuroscience Education to address psychosocial factors associated with acute low back pain: a case report. Physiotherapy theory and practice. 2014; 30(3):202-209.

Keller T and Krames ES. (2009). “On the Shoulders of Giants”: A History of the Understandings of Pain, Leading to the Understandings of Neuromodulation. Neuromodulation. 12 (2), 77-84.