Internal Impingement of the Shoulder: Difference between revisions

(spelling errors, removed pub med feed) |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

'''Top Contributors''' - {{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}} | '''Top Contributors''' - {{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}} | ||

== Definition/Description | == Definition/Description == | ||

Internal impingement is commonly described as a condition characterized by excessive or repetitive contact between the posterior aspect of the greater tuberosity of the humeral head and the posterior-superior aspect of the glenoid border when the arm is placed in extreme ranges of abduction and external rotation.<ref name=":0">Heyworth B, Williams R. Internal Impingement of the Shoulder. The American Journal of Sports Medicine. (2009) 37:1024-1037</ref><ref name=":9">Behrens S, Compas J, Deren M, Drakos M. Internal Impingement: A Review on a Common Cause of Shoulder Pain in Throwers. The Physician and Sportsmedicine. (2010) 38:2</ref><ref name=":1">Drakos M, Rudzki J, Allen A, Potter H, Altchek D. Internal Impingement of the Shoulder in the Overhead Athlete. Journal of Bone; Joint Surgery. (2009) 91:2719-2718</ref><ref name=":10">Jobe C, Coen M, Screnar P. Evaluation of Impingement Syndromes in the Overhead-Throwing Athlete. Journal of Athletic Training. (2000) 35:293-299</ref>This ultimately leads to impingement of the rotator cuff tendons (supraspinatus/infraspinatus) and the glenoid labrum. There are two types of internal impingement: anterosuperior and posterosuperior. Anterosuperior impingement occurs only rarely.<ref name=":2">Cools, A.M., et al. Internal impingement in the tennis player: rehabilitation guidelines. British Journal of Sports Medicine, (2008) 42, 165-171</ref><br> | Internal impingement is commonly described as a condition characterized by excessive or repetitive contact between the posterior aspect of the greater tuberosity of the humeral head and the posterior-superior aspect of the glenoid border when the arm is placed in extreme ranges of abduction and external rotation.<ref name=":0">Heyworth B, Williams R. Internal Impingement of the Shoulder. The American Journal of Sports Medicine. (2009) 37:1024-1037</ref><ref name=":9">Behrens S, Compas J, Deren M, Drakos M. Internal Impingement: A Review on a Common Cause of Shoulder Pain in Throwers. The Physician and Sportsmedicine. (2010) 38:2</ref><ref name=":1">Drakos M, Rudzki J, Allen A, Potter H, Altchek D. Internal Impingement of the Shoulder in the Overhead Athlete. Journal of Bone; Joint Surgery. (2009) 91:2719-2718</ref><ref name=":10">Jobe C, Coen M, Screnar P. Evaluation of Impingement Syndromes in the Overhead-Throwing Athlete. Journal of Athletic Training. (2000) 35:293-299</ref>This ultimately leads to impingement of the rotator cuff tendons (supraspinatus/infraspinatus) and the glenoid labrum. There are two types of internal impingement: anterosuperior and posterosuperior. Anterosuperior impingement occurs only rarely.<ref name=":2">Cools, A.M., et al. Internal impingement in the tennis player: rehabilitation guidelines. British Journal of Sports Medicine, (2008) 42, 165-171</ref><br> | ||

{{#ev:youtube|UzeGuzJJGlo}} | {{#ev:youtube|UzeGuzJJGlo}} | ||

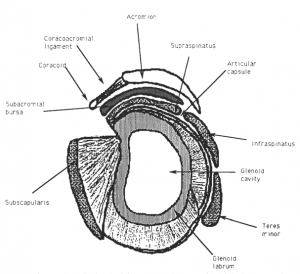

== Clinically Relevant Anatomy == | == Clinically Relevant Anatomy == | ||

The scapula is a flat blade lying along the thoracic wall. Because of the wide and thin configuration, it’s possible for the scapula to glide smoothly on the thoracic wall and provides a large surface area for muscle attachments, both distally and proximally.<ref name=":3">Kibler B. et al. The role of the scapula in athletic shoulder function. Am J Sports Med 1998;26:325–37</ref><br>The coracoacromial arch and the subacromial elements are important elements of anatomy related to internal impingement. As the name implies, the coracoacromial arch is formed by the coracoid and the acromion processes and the connecting coracoacromial ligaments. It protects the humeral head and subacromial structures from direct trauma and superior dislocation of the humeral head. Impingement may occur when the rotator cuff and other subacromial structures become encroached between the greater tuberosity and the coracoacromial arch. | The scapula is a flat blade lying along the thoracic wall. Because of the wide and thin configuration, it’s possible for the scapula to glide smoothly on the thoracic wall and provides a large surface area for muscle attachments, both distally and proximally.<ref name=":3">Kibler B. et al. The role of the scapula in athletic shoulder function. Am J Sports Med 1998;26:325–37</ref><br>The coracoacromial arch and the subacromial elements are important elements of anatomy related to internal impingement. As the name implies, the coracoacromial arch is formed by the coracoid and the acromion processes and the connecting coracoacromial ligaments. It protects the humeral head and subacromial structures from direct trauma and superior dislocation of the humeral head. Impingement may occur when the rotator cuff and other subacromial structures become encroached between the greater tuberosity and the coracoacromial arch. | ||

The tendons of the rotator cuff are: | |||

*Subscapularis tendon (anterior) | |||

*Supraspinatus tendon (superior) | |||

*Infraspinatus tendon (posterior) | |||

*Teres minor tendon (posterior) | |||

[[Image:Fysiopedia_1.png|300x300px]] | [[Image:Fysiopedia_1.png|300x300px]] | ||

| Line 26: | Line 27: | ||

The scapulothoracic articulation is a prime example of dynamic stability of the human body. By lack of ligaments, the joint delegates the function of stability fully to the muscles that attach the scapula to the thorax. So their proper function is essential to the normal biomechanics of the shoulder. | The scapulothoracic articulation is a prime example of dynamic stability of the human body. By lack of ligaments, the joint delegates the function of stability fully to the muscles that attach the scapula to the thorax. So their proper function is essential to the normal biomechanics of the shoulder. | ||

These muscles include: | These muscles include: | ||

*Serratus anterior | |||

*Trapezius | |||

*Levator scapulae | |||

*Rhomboid major | |||

*Rhomboid minor | |||

*Latisimus dorsi | |||

*Pectoralis major and minor | |||

*Supraspinatus and infraspinatus | |||

The serratus anterior and the trapezius has been suggested to be the most important muscles acting upon the scapulothoracic articulation.<ref name=":4" / | The serratus anterior and the trapezius has been suggested to be the most important muscles acting upon the scapulothoracic articulation.<ref name=":4" /> | ||

== Epidemiology /Etiology == | == Epidemiology /Etiology == | ||

=== Epidemiology === | |||

The incidence of internal impingement is unknown due to the variety of associated pathologic lesions and diagnostic difficulty.<ref name=":5">Ulrich J. Spiegl et al., Symptomatic Internal Impingement of the Shoulder in Overhead Athletes, Sports Med Arthrosc Rev Volume 22, Number 2, June 2014</ref>The majority of patients who have been identifies as having internal impingement are overhead athletes or throwing athletes (tennis, volleyball players and swimmers ).<ref name=":2" /> These patients participates in activities requiring repetitive external rotation and (hyper) abduction.<ref name=":5" />The majority of the research on internal impingement has been done on elite baseball players. However, non-elite athletes, as well as non-athletes may also be affected by internal impingement.<ref name=":0" /> With the non-elite athletic population, it is important to realize that older patients are more likely to have concurrent shoulder conditions.<ref name=":0" /> Since internal impingement is often involved with other pathology of the shoulder the incidence of it in isolation has not been established. | The incidence of internal impingement is unknown due to the variety of associated pathologic lesions and diagnostic difficulty.<ref name=":5">Ulrich J. Spiegl et al., Symptomatic Internal Impingement of the Shoulder in Overhead Athletes, Sports Med Arthrosc Rev Volume 22, Number 2, June 2014</ref>The majority of patients who have been identifies as having internal impingement are overhead athletes or throwing athletes (tennis, volleyball players and swimmers ).<ref name=":2" /> These patients participates in activities requiring repetitive external rotation and (hyper) abduction.<ref name=":5" />The majority of the research on internal impingement has been done on elite baseball players. However, non-elite athletes, as well as non-athletes may also be affected by internal impingement.<ref name=":0" /> With the non-elite athletic population, it is important to realize that older patients are more likely to have concurrent shoulder conditions.<ref name=":0" /> Since internal impingement is often involved with other pathology of the shoulder the incidence of it in isolation has not been established. | ||

=== Etiology === | |||

The understanding of the etiology behind internal impingement has gradually evolved but remains incomplete. The lack of a common biomechanical model is largely due to the limited patient population in which the syndrome is seen in as well as the thousands of associated pathologic findings that have been reported. Impingement has been described as a group of symptoms rather than a specific diagnosis.<ref name=":2" />In this current opinion, it is thought that numerous underlying pathologies may cause impingement symptoms. Glenohumeral instability<ref>Meister K. Injuries to the shoulder in the throwing athlete. Part one: biomechanics/pathophysiology/classification of injury. Am J Sports Med 2000;28:265–75</ref>, rotator cuff or biceps pathology<ref name=":0" />, scapular dyskinesis<ref name=":3" /><ref>Kamkar A et al. Non-operative management of secondary shoulder impingement syndrome. J Orthop Sports Phys Med 1993;17:212–24</ref> <ref name=":12">Burkhart S, et al.The disabled shoulder: spectrum of pathology partIII: the SICK scapula, scapular dyskinesis, the kinetic chain, and rehabilitation. Arthroscopy 2003;19:641–61</ref>, SLAP lesions and glenohumeral internal rotation deficit have been associated with impingement symptoms in clinical literature.<ref name=":6">Burkhart SS, et al. The disabled throwing shoulder: spectrum of pathology: Part I: pathoanatomy and biomechanics. Arthroscopy 2003;19:404–20</ref><br>In general, two pathological mechanisms in the possible aetiology of internal impingement have been described: | The understanding of the etiology behind internal impingement has gradually evolved but remains incomplete. The lack of a common biomechanical model is largely due to the limited patient population in which the syndrome is seen in as well as the thousands of associated pathologic findings that have been reported. Impingement has been described as a group of symptoms rather than a specific diagnosis.<ref name=":2" />In this current opinion, it is thought that numerous underlying pathologies may cause impingement symptoms. Glenohumeral instability<ref>Meister K. Injuries to the shoulder in the throwing athlete. Part one: biomechanics/pathophysiology/classification of injury. Am J Sports Med 2000;28:265–75</ref>, rotator cuff or biceps pathology<ref name=":0" />, scapular dyskinesis<ref name=":3" /><ref>Kamkar A et al. Non-operative management of secondary shoulder impingement syndrome. J Orthop Sports Phys Med 1993;17:212–24</ref> <ref name=":12">Burkhart S, et al.The disabled shoulder: spectrum of pathology partIII: the SICK scapula, scapular dyskinesis, the kinetic chain, and rehabilitation. Arthroscopy 2003;19:641–61</ref>, SLAP lesions and glenohumeral internal rotation deficit have been associated with impingement symptoms in clinical literature.<ref name=":6">Burkhart SS, et al. The disabled throwing shoulder: spectrum of pathology: Part I: pathoanatomy and biomechanics. Arthroscopy 2003;19:404–20</ref><br>In general, two pathological mechanisms in the possible aetiology of internal impingement have been described: | ||

| Line 51: | Line 60: | ||

The diagnosis of internal impingement based on history alone is extremely difficult, and symptoms tend to be variable and fairly nonspecific. <ref name=":0" /> A review of the literature does show several common symptoms that most internal impingement patients seem to share.<br>Internal Impingement patients present with: <br> | The diagnosis of internal impingement based on history alone is extremely difficult, and symptoms tend to be variable and fairly nonspecific. <ref name=":0" /> A review of the literature does show several common symptoms that most internal impingement patients seem to share.<br>Internal Impingement patients present with: <br> | ||

=== Posterior Shoulder Pain === | |||

*''Chronic''- diffuse posterior shoulder girdle pain is the chief complaint in the throwing athletes with internal impingement, but the pain may also be localized to the joint line.<ref name=":0" /> The patient may describe the onset of posterior shoulder pain, particularly during the late-cocking phase of throwing, when the arm is in 90° of abduction and full external rotation.<ref name=":9" /> | *''Chronic''- diffuse posterior shoulder girdle pain is the chief complaint in the throwing athletes with internal impingement, but the pain may also be localized to the joint line.<ref name=":0" /> The patient may describe the onset of posterior shoulder pain, particularly during the late-cocking phase of throwing, when the arm is in 90° of abduction and full external rotation.<ref name=":9" /> | ||

*''Acute'' – non-throwing athletes, who present with this syndrome, have a chief complaint of acute shoulder pain following injury | *''Acute'' – non-throwing athletes, who present with this syndrome, have a chief complaint of acute shoulder pain following injury | ||

*Decrease in throwing velocity''' - a progressive decrease in throwing velocity or loss of control and performance in the overhead athlete. | |||

*Dead arm - Some signs of the pathologic process include a so-called “dead arm,” the feeling of shoulder and arm weakness after throwing, and a subjective sense of slipping of the shoulder <ref name=":9" /> | |||

*Muscular Asymmetry''' - Overhead athletes and throwers in particular often have muscular asymmetry between the dominant and the nondominant shoulder. | |||

*Muscular/Neuromuscular Imbalance – A common finding is muscle imbalances in the shoulder complex as well as improper neuromuscular control of the scapula. <ref name=":11">Cools AM, Declercq G, Cagnie B, Cambier D, Witvrouw E. Internal Impingement in the Tennis Player: Rehabilitation Guidelines. British Journal of Sports Medicine. (2008) 42:164-171</ref> | |||

*Increased Laxity - A patient with isolated internal impingement may have an increase in global laxity or an increase in anterior laxity alone of the dominant shoulder. <ref name=":1" /> | |||

*Anterior Instability - Patients may have instability symptoms, such as apprehension or the sensation of subluxation with the arm in a position of abduction and external rotation.<ref name=":0" /> | |||

*Rotator Cuff Pathology - Patients may also present with symptoms similar to those associated with other rotator cuff pathologies (tears, other impingements). Younger patients with such symptoms, particularly throwing athletes, should raise the clinician’s index of suspicion for internal impingement. In fact, some authors have identified internal impingement as the leading cause of rotator cuff lesions in athletes. <ref name=":0" /> | |||

*A combination of internal derangement:''' popping, clicking, catching, sliding<ref name=":13">Kibler WB, Dome D. Internal impingement: concurrent superior labral androtator cuff injuries. Sports Med Arthrosc. 2012 Mar;20(1):30-3</ref> | |||

*Rotator cuff weakness <ref name=":13" /> Rotator cuff is a common name for the group of 4 distinct muscles (infraspinatus, supraspinatus, teres minor and subscapularis) and their tendons that provide strength and stability during motion of the shoulder. The four rotator cuff muscles may separately provide a disturbed muscle balance<ref>Phil Page et al., SHOULDER MUSCLE IMBALANCE AND SUBACROMIAL IMPINGEMENT SYNDROME IN OVERHEAD ATHLETES. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2011 Mar; 6(1): 51–58</ref>.<br><br>'''Jobe Clinical Classification of Internal Impingement'''

- Jobe developed a classification scheme to further distinguish between the varying severities of internal impingement.<ref name=":9" /> The Jobe classification system focuses on the primary patient population of overhead athletes.<ref name=":10" /> | |||

*Stage I: (Early)Shoulder stiffness and a prolonged warm-up period; discomfort in throwers occurs in the late-cocking and early acceleration phases of throwing; no pain is reported with activities of daily living. | |||

*Stage II: (Intermediate)Pain localized to the posterior shoulder in the late-cocking and early acceleration phases of throwing; pain with activities of daily living and instability are unusual. | |||

*Stage III: (advanced) Similar to those in stage II in patients who have not responded to nonoperative treatments.<br><br> | |||

== Differential Diagnosis == | == Differential Diagnosis == | ||

| Line 84: | Line 82: | ||

It is important to understand that the common findings for internal impingement have been found in asymptomatic shoulders so it is key to evaluate the patient's entire clinical scenario. The patient's age, profession, activity level, symptom severity, degreee of disability & the effects of this condition on their athletic performance need to be part of the clinicians decision making process. When exam findings are somewhat unremarkable, and when the patient presents with signs of numerous pathologies, yet do not seem to fit any one pathology exclusively, this should raise the clinicians suspicion for a case of internal impingement. During the diagnostic process it is helpful to understand that Internal impingement has a similar presentation to numerous pathologic shoulder conditions, including but not limited to:<ref name=":9" /><ref name=":1" /> | It is important to understand that the common findings for internal impingement have been found in asymptomatic shoulders so it is key to evaluate the patient's entire clinical scenario. The patient's age, profession, activity level, symptom severity, degreee of disability & the effects of this condition on their athletic performance need to be part of the clinicians decision making process. When exam findings are somewhat unremarkable, and when the patient presents with signs of numerous pathologies, yet do not seem to fit any one pathology exclusively, this should raise the clinicians suspicion for a case of internal impingement. During the diagnostic process it is helpful to understand that Internal impingement has a similar presentation to numerous pathologic shoulder conditions, including but not limited to:<ref name=":9" /><ref name=":1" /> | ||

*[https://www.physio-pedia.com/Rotator_Cuff_Tears Partial- or full-thickness rotator cuff tears] | |||

*Anterior or posterior capsular pathologies | |||

*[[SLAP Lesion|SLAP (Superior Labrum Anterior to Posterior) lesion]] | |||

*[[Subacromial Impingement|Subacromial Impingement]] | |||

*Glenoid chondral erosion | |||

*Chondromalacia of the posterosuperior humeral head | |||

*[https://www.physio-pedia.com/Anterior_Shoulder_Instability Anterior GH instability] | |||

*Biceps tendon lesion | |||

*Scapular Dysfunction | |||

Each of these disorders can exist alone or as concomitant pathological condition.<br><br> | |||

== Diagnostic Procedures == | == Diagnostic Procedures == | ||

| Line 106: | Line 112: | ||

When evaluating a patient with suspected internal impingement syndrome, it is very important to get a thorough history, as it is an important element of the clinical diagnosis.<ref name=":1" /> However, diagnosing internal impingement on the history alone is extremely difficult as symptoms tend to be variable and non-consistent.<ref name=":0" /> A thorough, complete examination of the shoulder complex must be done to rule in/out any concomitant shoulder pathologies. <br> | When evaluating a patient with suspected internal impingement syndrome, it is very important to get a thorough history, as it is an important element of the clinical diagnosis.<ref name=":1" /> However, diagnosing internal impingement on the history alone is extremely difficult as symptoms tend to be variable and non-consistent.<ref name=":0" /> A thorough, complete examination of the shoulder complex must be done to rule in/out any concomitant shoulder pathologies. <br> | ||

=== The basic exam === | |||

{| cellspacing="1" cellpadding="1" border="1" style="width: 696px; height: 401px;" | {| cellspacing="1" cellpadding="1" border="1" style="width: 696px; height: 401px;" | ||

| Line 168: | Line 174: | ||

<br>'''SICK Scapula''': Burkhart et al. have reported that scapular protraction is also a common finding in these patients.<ref name=":0" /> This is characterized by Scapular malposition, a prominent Inferior medial border, Coracoid pain, and scapular dysKinesia, all of which can be picked up in the basic examination during palpation and observation of the scapula. Tyler et al. reported that scapular retractor muscle fatigue led to an overall decrease in force production of the rotator cuff muscles as well as decreased strength of the scapular stabilizers.<ref name=":18">Tyler T, Nicholas S, Lee S, Mullaney M, McHugh M. Correction of Posterior Shoulder Tightness is Associated with Symptom Resolution in Patients with Internal Impingement. American Journal of Sports Medicine. (2010) 38:114-120</ref> | <br>'''SICK Scapula''': Burkhart et al. have reported that scapular protraction is also a common finding in these patients.<ref name=":0" /> This is characterized by Scapular malposition, a prominent Inferior medial border, Coracoid pain, and scapular dysKinesia, all of which can be picked up in the basic examination during palpation and observation of the scapula. Tyler et al. reported that scapular retractor muscle fatigue led to an overall decrease in force production of the rotator cuff muscles as well as decreased strength of the scapular stabilizers.<ref name=":18">Tyler T, Nicholas S, Lee S, Mullaney M, McHugh M. Correction of Posterior Shoulder Tightness is Associated with Symptom Resolution in Patients with Internal Impingement. American Journal of Sports Medicine. (2010) 38:114-120</ref> | ||

=== Tests for internal impingement === | |||

Recently, a small number of tests were created to help rule in/out the presence of internal impingement.<ref name=":0" /> | Recently, a small number of tests were created to help rule in/out the presence of internal impingement.<ref name=":0" /> | ||

* | *Posterior Impingement Sign: Meister et al. investigated the ability to detect articular sided rotator cuff tears and posterior labral lesions. They reported a sensitivity and specificity of 75.5% and 85% respectively, meaning a '''negative test is extremely accurate in ruling out posterior rotator cuff tears'''. A (+) test is indicated by the presence of deep posterior shoulder pain when the arm is brought nto a position of abduction to 90° to 110°, extension to 10° to 15°, and maximal external rotation.<ref name=":0" /> | ||

* | *[[Jobes Relocation Test|Relocation Test]]: Jobe and colleagues have reported this can be used to identify internal impingement. A positive test would be posterior shoulder pain that was relieved by a posterior directed force on the proximal humerus.<ref name=":0" /> | ||

But, there is insufficient evidence upon which to base selection of physical tests for shoulder impingements, and local lesions of bursa, tendon or labrum that may accompany impingement, in primary care. The large body of literature revealed extreme diversity in the performance and interpretation of tests, which hinders synthesis of the evidence and/or clinical applicability.<ref>Hanchard NC, Lenza M, Handoll HH, Takwoingi Y. Physical tests for shoulder impingements and local lesions of bursa, tendon or labrum that may accompany impingement. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 Apr 30;4:CD007427</ref><br> | But, there is insufficient evidence upon which to base selection of physical tests for shoulder impingements, and local lesions of bursa, tendon or labrum that may accompany impingement, in primary care. The large body of literature revealed extreme diversity in the performance and interpretation of tests, which hinders synthesis of the evidence and/or clinical applicability.<ref>Hanchard NC, Lenza M, Handoll HH, Takwoingi Y. Physical tests for shoulder impingements and local lesions of bursa, tendon or labrum that may accompany impingement. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 Apr 30;4:CD007427</ref><br> | ||

{{#ev:youtube|pahbl3RLPqA}} | {{#ev:youtube|pahbl3RLPqA}} | ||

=== Tests for associated conditions === | |||

'''Tests for other shoulder pathologies may be (+) or (-) '''due to the variable clinical presentation of internal impingement. Understand that there is no proven combination of test findings that identify internal impingement. | '''Tests for other shoulder pathologies may be (+) or (-) '''due to the variable clinical presentation of internal impingement. Understand that there is no proven combination of test findings that identify internal impingement. | ||

| Line 185: | Line 191: | ||

* [https://www.physio-pedia.com/Rotator_Cuff_Tears Full/partial thickness rotator cuff tears]: Test item clusters<br> | * [https://www.physio-pedia.com/Rotator_Cuff_Tears Full/partial thickness rotator cuff tears]: Test item clusters<br> | ||

'''SLAP Lesions:''' Although the validity of physical examination '''tests used to detect SLAP lesions''' is controversial, the fact that these lesions are a common finding with internal impingement warrants the need to perform at least some combination of the following tests: | '''SLAP Lesions:''' Although the validity of physical examination '''tests used to detect SLAP lesions''' is controversial, the fact that these lesions are a common finding with internal impingement warrants the need to perform at least some combination of the following tests: | ||

*[https://www.physio-pedia.com/O%27Briens_Test Active compression test] | *[https://www.physio-pedia.com/O%27Briens_Test Active compression test] | ||

| Line 204: | Line 210: | ||

Surgical treatment<ref>Alexander L. Lazarides et al., Rotator cuff tears in young patients: a differentdisease than rotator cuff tears in elderlypatients, journal of Shoulder and elbow surgery, 2015</ref><br>Surgical intervention will be indicated when it includes failure of conservative management to resolve signs and symptoms of internal impingement after 3 months<ref name=":19">R. Michael Greiwe and Christopher S. Ahmad, Management of the Throwing Shoulder: Cuff, Labrum and Internal Impingement, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery</ref>. Surgery for internal impingement may be indicated if improvements have not been seen with a prolonged rehab protocol specifically designed to correct any impairments, imbalances, deficiencies and/or pathologic findings. For the surgical treatment, we have different approaches: | Surgical treatment<ref>Alexander L. Lazarides et al., Rotator cuff tears in young patients: a differentdisease than rotator cuff tears in elderlypatients, journal of Shoulder and elbow surgery, 2015</ref><br>Surgical intervention will be indicated when it includes failure of conservative management to resolve signs and symptoms of internal impingement after 3 months<ref name=":19">R. Michael Greiwe and Christopher S. Ahmad, Management of the Throwing Shoulder: Cuff, Labrum and Internal Impingement, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery</ref>. Surgery for internal impingement may be indicated if improvements have not been seen with a prolonged rehab protocol specifically designed to correct any impairments, imbalances, deficiencies and/or pathologic findings. For the surgical treatment, we have different approaches: | ||

*Arthroscopic interventions<ref name=":0" /> it is the preferred type of surgery. Prior to any surgical procedure it is highly recommended that a thorough exam under anesthesia (EUA) is done, as well as a diagnostic arthroscopy. Due to the often-confusing physical findings that may be associated with internal impingement, the final therapeutic surgical plan should be aimed at specific pathologic lesions related to patient symptoms that have been identified from an EUA and diagnostic arthroscopy. It’s recommended that the EUA specifically assess for GH ROM, any kind of subluxation, as well as a meticulous analysis for the presence of any instability.<ref name=":0" /> | |||

*Subacromial decompression<ref name=":19" /> | |||

*Debridement of rotator cuff tear<ref name=":19" /> | |||

*Completion of rotator cuff tear by arthroscopic repair<ref name=":19" /> | |||

== Physical Therapy Management (current best evidence) == | == Physical Therapy Management (current best evidence) == | ||

=== Prevention/Early Management: === | |||

If an overhead athlete report feelings of thightness, stiffness, or not loosening up, the pitcher should be removed from participation and started in a rehab program.<ref name=":10" /> It is important, before treatment is undertaken, to rule out other anterior instability pathology, including SLAP lesions, labral tears, and partial rotator cuff tears.<ref name=":10" /><br> | If an overhead athlete report feelings of thightness, stiffness, or not loosening up, the pitcher should be removed from participation and started in a rehab program.<ref name=":10" /> It is important, before treatment is undertaken, to rule out other anterior instability pathology, including SLAP lesions, labral tears, and partial rotator cuff tears.<ref name=":10" /><br> | ||

| Line 218: | Line 225: | ||

*Strengthening the shoulder; | *Strengthening the shoulder; | ||

*Closed kinetic chain exercices for stabilizing the rotator cuff muscles. | *Closed kinetic chain exercices for stabilizing the rotator cuff muscles. | ||

*GIRD (Glenohumeral internal rotation deficit)<ref name=":18" /> | |||

*Strengthening program for posterior capsule | *Strengthening program for posterior capsule | ||

*Muscle imbalance and/or improper neuromuscular control of the shoulder complex | |||

*Strengthening periscapular musculature and the rotatorcuff muscles to prevent over-angulation in the late cocking phase of throwing<ref name=":10" /><ref name=":12" /><ref name=":20" />. | |||

=== Routine management === | |||

{| width="100%" cellspacing="1" cellpadding="1" | |||

|- | |||

| {{#ev:youtube|XF6JvfpxRSg|412}} | |||

| {{#ev:youtube|cg6iS7xe4rk|412}} | |||

|} | |||

With early internal impingement, the thrower (the incidence of glenoid impingement in throwers, especially pitchers, is high) or involved patient reports the shoulder is stiff and not loosening up as it normally would. Three stages of internal impingement have been described (Table ).<ref name=":1" /><br>An initial focus on correcting muscle imbalances, instabilities and ROM deficits before beginning more complex dynamic exercises.<ref name=":10" /><ref name=":2" /><ref name=":12" /> (see Table 1 for protocol)<br> | |||

In 2008, Cools, et al. published guidelines for rehabbing internal impingement in tennis players based on clinical literature and clinical experience. Parts of these guidelines are backed by evidence, but many of the treatments discussed have not been validated with medical research, so until that research is conducted these guidelines may provide a foundational starting point for clinicians treating internal impingement. Realize that this protocol is geared toward the athletic population. However, it can be applied to the non-athletic population as well by incorporating activity-specific functional activities instead of sport-specific. A non-athlete may also not need to progress all the way to phase 3, which will depend on the activity level they wish to return to. | In 2008, Cools, et al. published guidelines for rehabbing internal impingement in tennis players based on clinical literature and clinical experience. Parts of these guidelines are backed by evidence, but many of the treatments discussed have not been validated with medical research, so until that research is conducted these guidelines may provide a foundational starting point for clinicians treating internal impingement. Realize that this protocol is geared toward the athletic population. However, it can be applied to the non-athletic population as well by incorporating activity-specific functional activities instead of sport-specific. A non-athlete may also not need to progress all the way to phase 3, which will depend on the activity level they wish to return to. | ||

==== Phase one ==== | |||

• Soft tissue mobilization such as: massage, relaxation, contract-relax and low-energy, highrepetition kinetic taining<ref name=":10" /><br>• the scapula setting: retraction, elevation, depression<ref name=":10" /><ref>Muraki T, Aoki M, Izumi T, Fujii M, Hidaka E, Miyamoto S. Lengthening of the pectoralis minor muscle during passive shoulder motions and stretching techniques: a cadaveric biomechanical study. Phys Ther. 2009;89(4):333–341</ref><br>• Joint mobilization: oscillation, holdstretch, and scapular side-lying distraction tonic and phasic muscle coordination<ref name=":10" /><br>• Increase shoulder ROM<ref name=":10" /><br>• Decrease posterior capsule tightness<ref name=":10" /><br>• Strengthening to rebuild soft tissue support<ref name=":10" /><ref name=":5" /><ref name=":19" /><ref>Philip W McClure et al., Shoulder Function and 3-Dimensional Kinematics in People With Shoulder Impingement Syndrome Before and After a 6-Week Exercise Program, September 2004</ref><br>• Neuromuscular re-education to prevent recurrence<ref name=":10" /><ref name=":11" /><br>• Restore proper muscle balance and endurance<ref name=":11" /><br>• Proprioceptive training and dynamic stability exercises<ref name=":11" /><br>• Closed chain exercises: are suggested because axial compression exercises that put stress through the joint in a weight-bearing position result in joint approximation and improved co-contraction of the rotator cuff muscles.<ref name=":11" /> <br>• Ultrasound and electrostimulation: for reducing the pain and inflammation<ref name=":14" /><br> | • Soft tissue mobilization such as: massage, relaxation, contract-relax and low-energy, highrepetition kinetic taining<ref name=":10" /><br>• the scapula setting: retraction, elevation, depression<ref name=":10" /><ref>Muraki T, Aoki M, Izumi T, Fujii M, Hidaka E, Miyamoto S. Lengthening of the pectoralis minor muscle during passive shoulder motions and stretching techniques: a cadaveric biomechanical study. Phys Ther. 2009;89(4):333–341</ref><br>• Joint mobilization: oscillation, holdstretch, and scapular side-lying distraction tonic and phasic muscle coordination<ref name=":10" /><br>• Increase shoulder ROM<ref name=":10" /><br>• Decrease posterior capsule tightness<ref name=":10" /><br>• Strengthening to rebuild soft tissue support<ref name=":10" /><ref name=":5" /><ref name=":19" /><ref>Philip W McClure et al., Shoulder Function and 3-Dimensional Kinematics in People With Shoulder Impingement Syndrome Before and After a 6-Week Exercise Program, September 2004</ref><br>• Neuromuscular re-education to prevent recurrence<ref name=":10" /><ref name=":11" /><br>• Restore proper muscle balance and endurance<ref name=":11" /><br>• Proprioceptive training and dynamic stability exercises<ref name=":11" /><br>• Closed chain exercises: are suggested because axial compression exercises that put stress through the joint in a weight-bearing position result in joint approximation and improved co-contraction of the rotator cuff muscles.<ref name=":11" /> <br>• Ultrasound and electrostimulation: for reducing the pain and inflammation<ref name=":14" /><br> | ||

==== Phase two ==== | |||

*Improve dynamic stability-restoration mucle balance:<ref name=":14" />more complex and activity specific exercises. With muscle imbalances already addressed, the therapist can begin to add dynamic movements into rehab using “tactile cueing” to ensure patient is engaging the scapular musculature before beginning a movement. Progress to verbal cueing.<ref name=":11" /> | |||

*Strengthening exercises: Target all shoulder and scapular musculature. Start introducing eccentric and open kinetic chain exercises in order to begin preparing for specific athletic overhead movements.<ref name=":11" /><ref name=":5" /><ref name=":19" /> | |||

*Mobilisations<ref name=":11" /><ref>Vermeulen et al., Comparison of High-Grade and LowGrade Mobilization Techniques in the Management of Adhesive Capsulitis of the Shoulder: Randomized Controlled Trial, Physical Therapy ,March 2006</ref><ref>Robert C. Manske et al., A Randomized Controlled Single-Blinded Comparison of Stretching Versus Stretching and Joint Mobilization for Posterior Shoulder Tightness Measured by Internal Rotation Motion Loss, April 2010</ref> | |||

==== Phase three ==== | |||

*'''Functional rehabilitation plan:''' Designed to prepare the athlete to return to full athletic activity. Strengthening exercises are continued and plyometrics are initiated using both hands and limiting external rotation at first, progressing to one handed drills and gradually working into increasing velocity and resistance. | *'''Functional rehabilitation plan:''' Designed to prepare the athlete to return to full athletic activity. Strengthening exercises are continued and plyometrics are initiated using both hands and limiting external rotation at first, progressing to one handed drills and gradually working into increasing velocity and resistance. | ||

=== Additional Considerations === | |||

Rehabbing the GIRD component: started immediately upon 1st treatment and continue throughout. Numerous RCT’s have shown that this internal rotation deficit can be decreased by performing stretches aimed at the posterior capsule; namely the “sleeper stretch” and the “cross body adduction stretch.” '''The sleeper stretch''' is performed with the patient lying on their injured side with the shoulder in 90° forward flexion, the scapula manually fixed into retraction, while glenohumeral internal rotation is performed passively. The patient should feel a stretch in the posterior aspect of the shoulder and not in the anterior portion, if they do, then reducing intensity and rotating the trunk slightly backwards can reduce the intensity of the stretch. | |||

The cross-body stretch is another popular stretch for the posterior capsule and can be performed by moving the arm into horizontal adduction. This stretch has been shown to be superior for stretching the posterior capsule and for increasing internal ROM. <ref name="McClure 2007">McClure P, Balaicuis J, Heiland D, Broersma M, Thorndike C, Wood A. A Randomized Controlled Comparison of Stretching Procedures for Posterior Shoulder Tightness. Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy. (2007) 37:108-114</ref><br> | |||

Joint mobilizations (mobs): GH anterior-posterior joint mobs can be used to help stretch the posterior capsule and increase internal rotation, however, if instability is noted on the initial exam, joint mobs should be avoided. Grade IV, end range, dorsal-glide mobilizations are performed with the patient supine with shoulder placed into 90 abduction, and either in neutral or end range internal rotation of the humerus (refer to pictures).<ref name=":11" /> | |||

Thoracic and cervicothoracic manipulation: spinal manipulations can be used to improve mobility in these regions and have proven therapeutic short and long term effects. Several studies have shown a significant improvement in symptoms of shoulder impingement syndrome when a thoracic manipulation was combined with exercise. The benefits of a thoracic or cervicothoracic manipulation for internal impingement have yet to be studied, but based on the similar presentation of these two syndromes and the low-risk to benefit ratio of manipulation, these procedures may add a huge benefit to treatment. <ref name=":20">Bang M, Deyle G. Comparison of Supervised Exercise With and Without Manual Physical Therapy for Patients With Shoulder Impingement Syndrome. Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy. (2000) 30:126-137</ref><ref name="Boyles">Boyles R, Ritland B, Miracle B, Barclay D, Faul M, Moore J, Koppenhaver S, Wainner R. The Short-Term Effects of Thoracic Spine Thrust Manipulation On Patients With Shoulder Impingement Syndrome. Manual Therapy. (2009) 14:375-380</ref> | |||

Whole body kinetic chain exercises: Incorporating this early in rehab has been recommended in order to prepare the athletes whole body for return to activity. Core stability, leg balance, and diagonal movement patterns can be used to incorporate the entire kinetic chain while simultaneously involving the shoulder as well. One example of this is simply adding a degree of instability to an exercise; doing external rotation exercises while sitting on an exercise ball or while performing a single leg stance by standing on the opposite leg of the arm you are working.<ref name=":11" /> | |||

<u>'''Table 1: Cools et al. protocol'''<br></u> | <u>'''Table 1: Cools et al. protocol'''<br></u> | ||

== Key Research == | == Key Research == | ||

*Hanchard N, et al. The Cochrane Library. Discussed the modified relocation test from Hammer 2000 and the posterior impingement sign from Meister 2004. Explained the testing procedures. | |||

*McClure P, et al. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy. (2007) - Compared the effectiveness of the cross body stretch vs. sleeper stretch for posterior capsule tightness. The cross body stretch was greater than the sleeper stretch in improving internal rotation but the small sample size did not allow for statistical significance. | |||

== Resources <br> == | == Resources <br> == | ||

| Line 289: | Line 280: | ||

{{#ev:youtube|pBkQ91fX2Ok|300}} {{#ev:youtube|_ZzFSCU0Y1Q|300}} {{#ev:youtube|hduMDqOgMAs|300}}<br> | {{#ev:youtube|pBkQ91fX2Ok|300}} {{#ev:youtube|_ZzFSCU0Y1Q|300}} {{#ev:youtube|hduMDqOgMAs|300}}<br> | ||

== Clinical Bottom Line == | == Clinical Bottom Line == | ||

Revision as of 20:03, 10 January 2018

Original Editors - Joshua Caldwell, Phillip Williams, Gary Diekhoff, Bryan McAdams as part of the Texas State University Evidence-based Practice Project,Huart Deborah

Top Contributors - Joshua Caldwell, Phillip Williams, Gary Diekhoff, Bryan McAdams, Rachael Lowe, Kim Jackson, Admin, Evi Jacobs, Deborah Huart, Mandeepa Kumawat, Tarina van der Stockt, Fasuba Ayobami, Katherine Knight, Naomi O'Reilly, George Prudden, WikiSysop, Jess Bell, Jelle Habay, Simisola Ajeyalemi, Wanda van Niekerk, Robin Tacchetti and Jeremy Brady

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

Internal impingement is commonly described as a condition characterized by excessive or repetitive contact between the posterior aspect of the greater tuberosity of the humeral head and the posterior-superior aspect of the glenoid border when the arm is placed in extreme ranges of abduction and external rotation.[1][2][3][4]This ultimately leads to impingement of the rotator cuff tendons (supraspinatus/infraspinatus) and the glenoid labrum. There are two types of internal impingement: anterosuperior and posterosuperior. Anterosuperior impingement occurs only rarely.[5]

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

The scapula is a flat blade lying along the thoracic wall. Because of the wide and thin configuration, it’s possible for the scapula to glide smoothly on the thoracic wall and provides a large surface area for muscle attachments, both distally and proximally.[6]

The coracoacromial arch and the subacromial elements are important elements of anatomy related to internal impingement. As the name implies, the coracoacromial arch is formed by the coracoid and the acromion processes and the connecting coracoacromial ligaments. It protects the humeral head and subacromial structures from direct trauma and superior dislocation of the humeral head. Impingement may occur when the rotator cuff and other subacromial structures become encroached between the greater tuberosity and the coracoacromial arch.

The tendons of the rotator cuff are:

- Subscapularis tendon (anterior)

- Supraspinatus tendon (superior)

- Infraspinatus tendon (posterior)

- Teres minor tendon (posterior)

The rotatorcuff stabililizes the shoulder against the action of the prime movers to prevent excessive anterior, posterior, superior, or inferior humeral head translation.[7]

The rotatorcuff tear is located on the articular side of the rotator cuff, typically at the intersection of the infraspinatus and supraspinatus insertions onto the humeral head[3].

The scapulothoracic articulation is a prime example of dynamic stability of the human body. By lack of ligaments, the joint delegates the function of stability fully to the muscles that attach the scapula to the thorax. So their proper function is essential to the normal biomechanics of the shoulder.

These muscles include:

- Serratus anterior

- Trapezius

- Levator scapulae

- Rhomboid major

- Rhomboid minor

- Latisimus dorsi

- Pectoralis major and minor

- Supraspinatus and infraspinatus

The serratus anterior and the trapezius has been suggested to be the most important muscles acting upon the scapulothoracic articulation.[7]

Epidemiology /Etiology[edit | edit source]

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

The incidence of internal impingement is unknown due to the variety of associated pathologic lesions and diagnostic difficulty.[8]The majority of patients who have been identifies as having internal impingement are overhead athletes or throwing athletes (tennis, volleyball players and swimmers ).[5] These patients participates in activities requiring repetitive external rotation and (hyper) abduction.[8]The majority of the research on internal impingement has been done on elite baseball players. However, non-elite athletes, as well as non-athletes may also be affected by internal impingement.[1] With the non-elite athletic population, it is important to realize that older patients are more likely to have concurrent shoulder conditions.[1] Since internal impingement is often involved with other pathology of the shoulder the incidence of it in isolation has not been established.

Etiology[edit | edit source]

The understanding of the etiology behind internal impingement has gradually evolved but remains incomplete. The lack of a common biomechanical model is largely due to the limited patient population in which the syndrome is seen in as well as the thousands of associated pathologic findings that have been reported. Impingement has been described as a group of symptoms rather than a specific diagnosis.[5]In this current opinion, it is thought that numerous underlying pathologies may cause impingement symptoms. Glenohumeral instability[9], rotator cuff or biceps pathology[1], scapular dyskinesis[6][10] [11], SLAP lesions and glenohumeral internal rotation deficit have been associated with impingement symptoms in clinical literature.[12]

In general, two pathological mechanisms in the possible aetiology of internal impingement have been described:

- excessive humeral translations, compromising glenohumeral congruence,

- scapular dyskinesis, decreasing the quality of functional scapular stability.[1][13][14]

Anterior GH instability: Jobe et al. hypothesized that anterior instability/laxity of the shoulder complex caused by repetitive stretching of the anterior GH capsule led to this type of impingement in throwing athletes. This laxity allows for increased anterior humeral head translation.[1]This type of acquired instability is often referred to as acquired instability overuse syndrome (AIOS).[15]

Tight posterior GH capsule: The posterior-inferior GH joint capsule is hypothesized to become hypertrophied in the follow-through tensile motion of throwing.[16]The tightness of the posterior capsule and the muscle tendon unit of the posterior rotator cuff is believed to limit internal joint rotation.[12] Posterior capsule tightness leads to GIRD (glenohumeral internal rotation deficit).[13][14] Burkhart[12] et al. defined GIRD as a loss of internal rotation of >20° compared with the contralateral side. When the posterior structures of the glenohumeral joint are shortened, this may compromise the hammock function of the inferior glenohumeral ligament (IGHL), and increase the risk for impingement symptoms during throwing.

Muscle imbalance and/or improper neuromuscular control of the shoulder complex: Jobe et al. also reported that malpositioning of the arm relative to the glenoid bone during throwing motions can also lead to impingement of the rotator cuff tendons between the glenolabral complex and the humeral head.[1] Fatigue and/or weakness of the scapular retractors have been shown to cause a decreased force production in all four of the rotator cuff muscles, which would also lead to abnormal positioning of the GH joint.[17][18] At the base of this abnormal scapular positioning lies the lack of neuromuscular control of the periscapular musculature as well as muscle imbalances between the rotator cuff and upward rotators of the scapula (serratus anterior, upper trap, lower trap).

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

The diagnosis of internal impingement based on history alone is extremely difficult, and symptoms tend to be variable and fairly nonspecific. [1] A review of the literature does show several common symptoms that most internal impingement patients seem to share.

Internal Impingement patients present with:

Posterior Shoulder Pain[edit | edit source]

- Chronic- diffuse posterior shoulder girdle pain is the chief complaint in the throwing athletes with internal impingement, but the pain may also be localized to the joint line.[1] The patient may describe the onset of posterior shoulder pain, particularly during the late-cocking phase of throwing, when the arm is in 90° of abduction and full external rotation.[2]

- Acute – non-throwing athletes, who present with this syndrome, have a chief complaint of acute shoulder pain following injury

- Decrease in throwing velocity - a progressive decrease in throwing velocity or loss of control and performance in the overhead athlete.

- Dead arm - Some signs of the pathologic process include a so-called “dead arm,” the feeling of shoulder and arm weakness after throwing, and a subjective sense of slipping of the shoulder [2]

- Muscular Asymmetry - Overhead athletes and throwers in particular often have muscular asymmetry between the dominant and the nondominant shoulder.

- Muscular/Neuromuscular Imbalance – A common finding is muscle imbalances in the shoulder complex as well as improper neuromuscular control of the scapula. [19]

- Increased Laxity - A patient with isolated internal impingement may have an increase in global laxity or an increase in anterior laxity alone of the dominant shoulder. [3]

- Anterior Instability - Patients may have instability symptoms, such as apprehension or the sensation of subluxation with the arm in a position of abduction and external rotation.[1]

- Rotator Cuff Pathology - Patients may also present with symptoms similar to those associated with other rotator cuff pathologies (tears, other impingements). Younger patients with such symptoms, particularly throwing athletes, should raise the clinician’s index of suspicion for internal impingement. In fact, some authors have identified internal impingement as the leading cause of rotator cuff lesions in athletes. [1]

- A combination of internal derangement: popping, clicking, catching, sliding[20]

- Rotator cuff weakness [20] Rotator cuff is a common name for the group of 4 distinct muscles (infraspinatus, supraspinatus, teres minor and subscapularis) and their tendons that provide strength and stability during motion of the shoulder. The four rotator cuff muscles may separately provide a disturbed muscle balance[21].

Jobe Clinical Classification of Internal Impingement - Jobe developed a classification scheme to further distinguish between the varying severities of internal impingement.[2] The Jobe classification system focuses on the primary patient population of overhead athletes.[4]

- Stage I: (Early)Shoulder stiffness and a prolonged warm-up period; discomfort in throwers occurs in the late-cocking and early acceleration phases of throwing; no pain is reported with activities of daily living.

- Stage II: (Intermediate)Pain localized to the posterior shoulder in the late-cocking and early acceleration phases of throwing; pain with activities of daily living and instability are unusual.

- Stage III: (advanced) Similar to those in stage II in patients who have not responded to nonoperative treatments.

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

It is important to understand that the common findings for internal impingement have been found in asymptomatic shoulders so it is key to evaluate the patient's entire clinical scenario. The patient's age, profession, activity level, symptom severity, degreee of disability & the effects of this condition on their athletic performance need to be part of the clinicians decision making process. When exam findings are somewhat unremarkable, and when the patient presents with signs of numerous pathologies, yet do not seem to fit any one pathology exclusively, this should raise the clinicians suspicion for a case of internal impingement. During the diagnostic process it is helpful to understand that Internal impingement has a similar presentation to numerous pathologic shoulder conditions, including but not limited to:[2][3]

- Partial- or full-thickness rotator cuff tears

- Anterior or posterior capsular pathologies

- SLAP (Superior Labrum Anterior to Posterior) lesion

- Subacromial Impingement

- Glenoid chondral erosion

- Chondromalacia of the posterosuperior humeral head

- Anterior GH instability

- Biceps tendon lesion

- Scapular Dysfunction

Each of these disorders can exist alone or as concomitant pathological condition.

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

In many situations the diagnosis of internal impingement is made through the physical examination along with MRI[22] and radiographs. Magnetic resonance imaging has been used frequently to diagnose pathologic conditions of the shoulder. Its sensitivity and specificity for the detection of labral tears and rotator cuff disease are on the order of ‡95%. Magnetic resonance imaging has the advantage of being able to detect intrasubstance tears that may be difficult to visualize with arthroscopy. The findings of magnetic resonance imaging of patients with internal impingement are usually more subtle. Findings on magnetic resonance imaging of patients with internal impingement include mature periosteal bone formation at the scapular attachement of the posterior aspect of the capsule (The Bennet lesion) and moderate to severe posterior capsular contracture at the level of the posterior band of the inferior glenohumeral ligament.[3]

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

Shoulder Disability Questionnaire (SDQ)

The SDQ is a measure covering 16 items designed to evaluate functional status limitation in patients with shoulder disorders.[23] This questionnaire is a valid and reliable instrument.[23][24][25]

Shoulder Pain and Disability Index (SPADI)

The SPADI developed by Roach et al., consists of a separate 5-item pain scale and an 8-item disability scale, with the preceding week as the recall frame.[23]The questionnaire was found to have good internal consistency, test re-test reliability, and criteria and construct validity in a sample of 37 male outpatients with shoulder complaints.[26][24][25]

Shoulder Rating Questionnaire (SRQ)

Shoulder Rating Questionnaire by l'Insalata et al. consists of 19 items with a 5-point ordinal answer scale: 4 relate to pain, 6 to daily activities, 3 to recreational and athletic activities, 5 to work, and 1 to satisfaction. The Shoulder Rating Questionnaire also includes a visual analogue scale for global assessment, as well as an item to indicate the domain of most important improvement.[23][24]

Other frequently used questionnaires to determine the progression of symptoms such as pain, disability and other outcomes=

- Simple Shoulder Test (SST)

- Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand (DASH)

- Constant-Murley Scale (CMS)

- Oxford Shoulder Instability Score (OSIS)

Examination and Clinical Findings[edit | edit source]

When evaluating a patient with suspected internal impingement syndrome, it is very important to get a thorough history, as it is an important element of the clinical diagnosis.[3] However, diagnosing internal impingement on the history alone is extremely difficult as symptoms tend to be variable and non-consistent.[1] A thorough, complete examination of the shoulder complex must be done to rule in/out any concomitant shoulder pathologies.

The basic exam[edit | edit source]

| Clinical Technique |

Findings |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Variable: General Considerations

|

|

|

SICK Scapula: Burkhart et al. have reported that scapular protraction is also a common finding in these patients.[1] This is characterized by Scapular malposition, a prominent Inferior medial border, Coracoid pain, and scapular dysKinesia, all of which can be picked up in the basic examination during palpation and observation of the scapula. Tyler et al. reported that scapular retractor muscle fatigue led to an overall decrease in force production of the rotator cuff muscles as well as decreased strength of the scapular stabilizers.[27]

Tests for internal impingement[edit | edit source]

Recently, a small number of tests were created to help rule in/out the presence of internal impingement.[1]

- Posterior Impingement Sign: Meister et al. investigated the ability to detect articular sided rotator cuff tears and posterior labral lesions. They reported a sensitivity and specificity of 75.5% and 85% respectively, meaning a negative test is extremely accurate in ruling out posterior rotator cuff tears. A (+) test is indicated by the presence of deep posterior shoulder pain when the arm is brought nto a position of abduction to 90° to 110°, extension to 10° to 15°, and maximal external rotation.[1]

- Relocation Test: Jobe and colleagues have reported this can be used to identify internal impingement. A positive test would be posterior shoulder pain that was relieved by a posterior directed force on the proximal humerus.[1]

But, there is insufficient evidence upon which to base selection of physical tests for shoulder impingements, and local lesions of bursa, tendon or labrum that may accompany impingement, in primary care. The large body of literature revealed extreme diversity in the performance and interpretation of tests, which hinders synthesis of the evidence and/or clinical applicability.[28]

Tests for associated conditions[edit | edit source]

Tests for other shoulder pathologies may be (+) or (-) due to the variable clinical presentation of internal impingement. Understand that there is no proven combination of test findings that identify internal impingement.

- Subacromial Impingement: Test item cluster

- Full/partial thickness rotator cuff tears: Test item clusters

SLAP Lesions: Although the validity of physical examination tests used to detect SLAP lesions is controversial, the fact that these lesions are a common finding with internal impingement warrants the need to perform at least some combination of the following tests:

Laxity of the anterior GH joint capsule: The following have proven diagnostic accuracy: Generally (+) but may be (-)

- The apprehension test

- Jobe subluxation/relocation test

- Anterior release test

Medical Management (current best evidence)[edit | edit source]

Conservative management of internal impingement is an appropriate initial approach, particularly in patient who do not report an acute traumatic event.[2]We can divide the medical management in non-surgical treatment and surgical treatment.

Non-surgical treatment[2][3][8]

Interventions that are recommended in the literature in early disease when the shoulder is stiff and can be poorly localized are:

• Rest;

• Ice (cryotherapy);

• NSAID’s (or other oral-anti-inflammatory meds);

• corticosteroid injection[22]

→All this interventions will be used in addition to a structured, supervised physical therapy regimen.[8]

Surgical treatment[29]

Surgical intervention will be indicated when it includes failure of conservative management to resolve signs and symptoms of internal impingement after 3 months[30]. Surgery for internal impingement may be indicated if improvements have not been seen with a prolonged rehab protocol specifically designed to correct any impairments, imbalances, deficiencies and/or pathologic findings. For the surgical treatment, we have different approaches:

- Arthroscopic interventions[1] it is the preferred type of surgery. Prior to any surgical procedure it is highly recommended that a thorough exam under anesthesia (EUA) is done, as well as a diagnostic arthroscopy. Due to the often-confusing physical findings that may be associated with internal impingement, the final therapeutic surgical plan should be aimed at specific pathologic lesions related to patient symptoms that have been identified from an EUA and diagnostic arthroscopy. It’s recommended that the EUA specifically assess for GH ROM, any kind of subluxation, as well as a meticulous analysis for the presence of any instability.[1]

- Subacromial decompression[30]

- Debridement of rotator cuff tear[30]

- Completion of rotator cuff tear by arthroscopic repair[30]

Physical Therapy Management (current best evidence)[edit | edit source]

Prevention/Early Management:[edit | edit source]

If an overhead athlete report feelings of thightness, stiffness, or not loosening up, the pitcher should be removed from participation and started in a rehab program.[4] It is important, before treatment is undertaken, to rule out other anterior instability pathology, including SLAP lesions, labral tears, and partial rotator cuff tears.[4]

There are different injuries that are associated with internal impingement of the shoulder:

• Anterior GH instability[1]

- Strengthening the shoulder;

- Closed kinetic chain exercices for stabilizing the rotator cuff muscles.

- GIRD (Glenohumeral internal rotation deficit)[27]

- Strengthening program for posterior capsule

- Muscle imbalance and/or improper neuromuscular control of the shoulder complex

- Strengthening periscapular musculature and the rotatorcuff muscles to prevent over-angulation in the late cocking phase of throwing[4][11][31].

Routine management[edit | edit source]

With early internal impingement, the thrower (the incidence of glenoid impingement in throwers, especially pitchers, is high) or involved patient reports the shoulder is stiff and not loosening up as it normally would. Three stages of internal impingement have been described (Table ).[3]

An initial focus on correcting muscle imbalances, instabilities and ROM deficits before beginning more complex dynamic exercises.[4][5][11] (see Table 1 for protocol)

In 2008, Cools, et al. published guidelines for rehabbing internal impingement in tennis players based on clinical literature and clinical experience. Parts of these guidelines are backed by evidence, but many of the treatments discussed have not been validated with medical research, so until that research is conducted these guidelines may provide a foundational starting point for clinicians treating internal impingement. Realize that this protocol is geared toward the athletic population. However, it can be applied to the non-athletic population as well by incorporating activity-specific functional activities instead of sport-specific. A non-athlete may also not need to progress all the way to phase 3, which will depend on the activity level they wish to return to.

Phase one[edit | edit source]

• Soft tissue mobilization such as: massage, relaxation, contract-relax and low-energy, highrepetition kinetic taining[4]

• the scapula setting: retraction, elevation, depression[4][32]

• Joint mobilization: oscillation, holdstretch, and scapular side-lying distraction tonic and phasic muscle coordination[4]

• Increase shoulder ROM[4]

• Decrease posterior capsule tightness[4]

• Strengthening to rebuild soft tissue support[4][8][30][33]

• Neuromuscular re-education to prevent recurrence[4][19]

• Restore proper muscle balance and endurance[19]

• Proprioceptive training and dynamic stability exercises[19]

• Closed chain exercises: are suggested because axial compression exercises that put stress through the joint in a weight-bearing position result in joint approximation and improved co-contraction of the rotator cuff muscles.[19]

• Ultrasound and electrostimulation: for reducing the pain and inflammation[22]

Phase two[edit | edit source]

- Improve dynamic stability-restoration mucle balance:[22]more complex and activity specific exercises. With muscle imbalances already addressed, the therapist can begin to add dynamic movements into rehab using “tactile cueing” to ensure patient is engaging the scapular musculature before beginning a movement. Progress to verbal cueing.[19]

- Strengthening exercises: Target all shoulder and scapular musculature. Start introducing eccentric and open kinetic chain exercises in order to begin preparing for specific athletic overhead movements.[19][8][30]

- Mobilisations[19][34][35]

Phase three[edit | edit source]

- Functional rehabilitation plan: Designed to prepare the athlete to return to full athletic activity. Strengthening exercises are continued and plyometrics are initiated using both hands and limiting external rotation at first, progressing to one handed drills and gradually working into increasing velocity and resistance.

Additional Considerations[edit | edit source]

Rehabbing the GIRD component: started immediately upon 1st treatment and continue throughout. Numerous RCT’s have shown that this internal rotation deficit can be decreased by performing stretches aimed at the posterior capsule; namely the “sleeper stretch” and the “cross body adduction stretch.” The sleeper stretch is performed with the patient lying on their injured side with the shoulder in 90° forward flexion, the scapula manually fixed into retraction, while glenohumeral internal rotation is performed passively. The patient should feel a stretch in the posterior aspect of the shoulder and not in the anterior portion, if they do, then reducing intensity and rotating the trunk slightly backwards can reduce the intensity of the stretch.

The cross-body stretch is another popular stretch for the posterior capsule and can be performed by moving the arm into horizontal adduction. This stretch has been shown to be superior for stretching the posterior capsule and for increasing internal ROM. [36]

Joint mobilizations (mobs): GH anterior-posterior joint mobs can be used to help stretch the posterior capsule and increase internal rotation, however, if instability is noted on the initial exam, joint mobs should be avoided. Grade IV, end range, dorsal-glide mobilizations are performed with the patient supine with shoulder placed into 90 abduction, and either in neutral or end range internal rotation of the humerus (refer to pictures).[19]

Thoracic and cervicothoracic manipulation: spinal manipulations can be used to improve mobility in these regions and have proven therapeutic short and long term effects. Several studies have shown a significant improvement in symptoms of shoulder impingement syndrome when a thoracic manipulation was combined with exercise. The benefits of a thoracic or cervicothoracic manipulation for internal impingement have yet to be studied, but based on the similar presentation of these two syndromes and the low-risk to benefit ratio of manipulation, these procedures may add a huge benefit to treatment. [31][37]

Whole body kinetic chain exercises: Incorporating this early in rehab has been recommended in order to prepare the athletes whole body for return to activity. Core stability, leg balance, and diagonal movement patterns can be used to incorporate the entire kinetic chain while simultaneously involving the shoulder as well. One example of this is simply adding a degree of instability to an exercise; doing external rotation exercises while sitting on an exercise ball or while performing a single leg stance by standing on the opposite leg of the arm you are working.[19]

Table 1: Cools et al. protocol

Key Research[edit | edit source]

- Hanchard N, et al. The Cochrane Library. Discussed the modified relocation test from Hammer 2000 and the posterior impingement sign from Meister 2004. Explained the testing procedures.

- McClure P, et al. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy. (2007) - Compared the effectiveness of the cross body stretch vs. sleeper stretch for posterior capsule tightness. The cross body stretch was greater than the sleeper stretch in improving internal rotation but the small sample size did not allow for statistical significance.

Resources

[edit | edit source]

- http://www.eorif.com/Shoulderarm/Throwing%20Athlete.html

- http://eorif.com/Shoulderarm/internal%20impingment.html

- http://www.throwinginjuries.com/Rotator%20Cuff%20Tears.htm

- Overview of the shoulder complex: Key elements

Clinical Bottom Line[edit | edit source]

Internal impingement can come across as a very difficult diagnosis to evaluate and treat due the fact that the symptoms tend to be variable and fairly nonspecific. However, it is important to realize that this diagnosis, just like most shoulder conditions, is really impairment-based; it just happens to have a name attached to it. That said, an impairment-based treatment approach aimed at the individual clinical findings should be the treatment of choice. The three most common impairments that have been found to contribute to internal impingement, and that need to be addressed from day 1 include:

• Anterior GH instability

• Tight posterior GH capsule

• Muscle imbalance and/or improper neuromuscular control of the shoulder complex

Based on these findings the treatment of internal impingement needs to include joint mobilizations and stretching to stretch the capsule of the shoulder and the strained muscles. As well as muscle strengthening to avoid these muscle imbalances and the instability of the shoulder.

Surgical treatment is indicated if after 3 months of physical therapy no significant improvements in symptoms are seen.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 Heyworth B, Williams R. Internal Impingement of the Shoulder. The American Journal of Sports Medicine. (2009) 37:1024-1037

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 Behrens S, Compas J, Deren M, Drakos M. Internal Impingement: A Review on a Common Cause of Shoulder Pain in Throwers. The Physician and Sportsmedicine. (2010) 38:2

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 Drakos M, Rudzki J, Allen A, Potter H, Altchek D. Internal Impingement of the Shoulder in the Overhead Athlete. Journal of Bone; Joint Surgery. (2009) 91:2719-2718

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 Jobe C, Coen M, Screnar P. Evaluation of Impingement Syndromes in the Overhead-Throwing Athlete. Journal of Athletic Training. (2000) 35:293-299

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Cools, A.M., et al. Internal impingement in the tennis player: rehabilitation guidelines. British Journal of Sports Medicine, (2008) 42, 165-171

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Kibler B. et al. The role of the scapula in athletic shoulder function. Am J Sports Med 1998;26:325–37

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Abdulazeem K, et al.; Nonoperative Management of Secondary Shoulder Impingement Syndrome; Journal of Orthopaedic & Sport Physical Therapy; Volume 17-5;1993

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 Ulrich J. Spiegl et al., Symptomatic Internal Impingement of the Shoulder in Overhead Athletes, Sports Med Arthrosc Rev Volume 22, Number 2, June 2014

- ↑ Meister K. Injuries to the shoulder in the throwing athlete. Part one: biomechanics/pathophysiology/classification of injury. Am J Sports Med 2000;28:265–75

- ↑ Kamkar A et al. Non-operative management of secondary shoulder impingement syndrome. J Orthop Sports Phys Med 1993;17:212–24

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Burkhart S, et al.The disabled shoulder: spectrum of pathology partIII: the SICK scapula, scapular dyskinesis, the kinetic chain, and rehabilitation. Arthroscopy 2003;19:641–61

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Burkhart SS, et al. The disabled throwing shoulder: spectrum of pathology: Part I: pathoanatomy and biomechanics. Arthroscopy 2003;19:404–20

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Myers J, Oyama S, Wassinger C, Ricci R, Abt J, Conley K. Reliability, Precision, Accuracy, and Validity of Posterior Shoulder Tightness Assessment in Overhead Athletes. American Journal of Sports Medicine. (2007) 35:1922-1932

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Myers J, Laudner K, Pasquale M, Bradley J, Lephart S. Posterior Shoulder Tightness in Throwers with Pathologic Internal Impingement. The American Journal of Sports Medicine. (2006) 34:385-391

- ↑ Wilk KE, et al. Current concepts in the rehabilitation of the overhead throwing athlete. Am J Sports Med 2002;30:136–151

- ↑ Preston C, Maison C, House T. Risk Assessment and Prevention of Arm Injuries in Baseball Players. Journal of Musculoskeletal Medicine. (2009) 26:149-153

- ↑ Tyler T, Cuoco A, Schachter A, Thomas G, McHugh M. The Effect of Scapular-Retractor Fatigue on External and Internal Rotation in Patients with Internal Impingement. Journal of Sports Rehabilitation. (2009) 18:229-239

- ↑ Mihata T, Gates J, McGarry M, Lee J, Kinoshita M, Lee T. Effect of Rotator Cuff Muscle Imbalance on Forceful Internal Impingement and Peel-Back of the Superior Labrum: A Cadaveric Study. American Journal of Sports Medicine. (2009) 37:2222-2227,

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 19.4 19.5 19.6 19.7 19.8 19.9 Cools AM, Declercq G, Cagnie B, Cambier D, Witvrouw E. Internal Impingement in the Tennis Player: Rehabilitation Guidelines. British Journal of Sports Medicine. (2008) 42:164-171

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Kibler WB, Dome D. Internal impingement: concurrent superior labral androtator cuff injuries. Sports Med Arthrosc. 2012 Mar;20(1):30-3

- ↑ Phil Page et al., SHOULDER MUSCLE IMBALANCE AND SUBACROMIAL IMPINGEMENT SYNDROME IN OVERHEAD ATHLETES. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2011 Mar; 6(1): 51–58

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 Chlodwig Kirchhoff & Andreas B. Imhoff, Posterosuperior and anterosuperior impingement of the shoulder in overhead athletes—evolving concepts, : 20 March 2010

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 Heijden van der GJ, Leffers P, Bouter LM. Shoulder Disability Questionnaire design and responsiveness of a functional status measure. J Clin Epidemiol 2000: 53 (1): 29-38

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 Paul A, et al. A comparison of four shoulder-specific questionnaires in primary care. Ann Rheum Dis 2004;63:1293-1299.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Bot SDM, et al. Clinimetric evaluation of shoulder disability questionnaires: a systematic review of the literature. Ann Rheum Dis 2004; 63: 335-341

- ↑ Croft P, et al. Measurement of shoulder related disability: results of a validation study. Ann Rheum Dis 1994;53:525–8

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Tyler T, Nicholas S, Lee S, Mullaney M, McHugh M. Correction of Posterior Shoulder Tightness is Associated with Symptom Resolution in Patients with Internal Impingement. American Journal of Sports Medicine. (2010) 38:114-120

- ↑ Hanchard NC, Lenza M, Handoll HH, Takwoingi Y. Physical tests for shoulder impingements and local lesions of bursa, tendon or labrum that may accompany impingement. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 Apr 30;4:CD007427

- ↑ Alexander L. Lazarides et al., Rotator cuff tears in young patients: a differentdisease than rotator cuff tears in elderlypatients, journal of Shoulder and elbow surgery, 2015

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 30.3 30.4 30.5 R. Michael Greiwe and Christopher S. Ahmad, Management of the Throwing Shoulder: Cuff, Labrum and Internal Impingement, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Bang M, Deyle G. Comparison of Supervised Exercise With and Without Manual Physical Therapy for Patients With Shoulder Impingement Syndrome. Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy. (2000) 30:126-137

- ↑ Muraki T, Aoki M, Izumi T, Fujii M, Hidaka E, Miyamoto S. Lengthening of the pectoralis minor muscle during passive shoulder motions and stretching techniques: a cadaveric biomechanical study. Phys Ther. 2009;89(4):333–341

- ↑ Philip W McClure et al., Shoulder Function and 3-Dimensional Kinematics in People With Shoulder Impingement Syndrome Before and After a 6-Week Exercise Program, September 2004

- ↑ Vermeulen et al., Comparison of High-Grade and LowGrade Mobilization Techniques in the Management of Adhesive Capsulitis of the Shoulder: Randomized Controlled Trial, Physical Therapy ,March 2006

- ↑ Robert C. Manske et al., A Randomized Controlled Single-Blinded Comparison of Stretching Versus Stretching and Joint Mobilization for Posterior Shoulder Tightness Measured by Internal Rotation Motion Loss, April 2010

- ↑ McClure P, Balaicuis J, Heiland D, Broersma M, Thorndike C, Wood A. A Randomized Controlled Comparison of Stretching Procedures for Posterior Shoulder Tightness. Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy. (2007) 37:108-114

- ↑ Boyles R, Ritland B, Miracle B, Barclay D, Faul M, Moore J, Koppenhaver S, Wainner R. The Short-Term Effects of Thoracic Spine Thrust Manipulation On Patients With Shoulder Impingement Syndrome. Manual Therapy. (2009) 14:375-380