Hallux Valgus

Original Editors - Bradley Svoboda

Top Contributors - Laura Ritchie, Van Horebeek Erika, Mariam Hashem, Ewa Jaraczewska, Lucinda hampton, Jolien Rottie, Rachael Lowe, Jess Bell, Bradley Svoboda, Andeela Hafeez, Kim Jackson, Admin, Morgane Michiels, 127.0.0.1, Kristin Zumo, Khloud Shreif, Tarina van der Stockt, WikiSysop, Tinne Tielemans, Wanda van Niekerk and Evan Thomas

Definition[edit | edit source]

Hallux valgus is the most common foot deformity[1].

- It is a progressive foot deformity in which the first metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint is affected and is often accompanied by significant functional disability and foot pain[2][3] and reduced quality of life[4][4]

- This joint is gradually subluxed (lateral deviation of the MTP joint) resulting in abduction of the first metatarsal while the phalanges adduct[2][5]

- This often leads to the development of soft tissue and bony prominence on the medial side of what is called a bunion [6] (exostosis on the dorsomedial aspect of the first metatarsal head)[7]

- At a late stage, these changes lead to pain and functional deficit: i.e. impaired gait (lateral and posterior weight shift, late heel rise, decreased single-limb balance, pronation deformity) [5]

- There is a high prevalence of hallux valgus in the overall population (23% of adults aged 18-65 years and 35.7% of adults over 65 years of age)

- There is a higher prevalence in women (females 30% - males 13%) and the elderly (35.7%)[8][3]

- It is more common in individuals with flat feet or hammer toes[4]

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

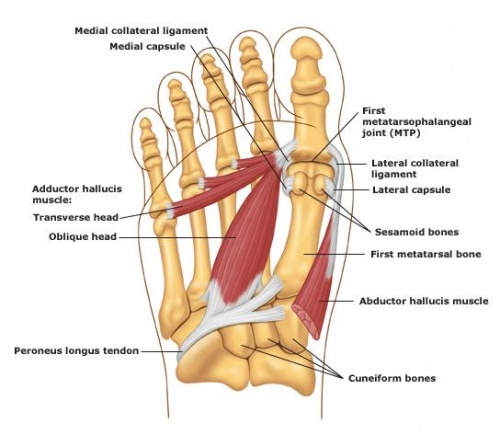

The Hallux or first toe is the medio-distal part of the foot.

- Formed by the first metatarsal (articulates with two sesamoid bones), the first proximal phalanx and the first distal phalanx.

- Formed by three bones instead of four, unlike the other toes who have an extra bone called the intermediate phalanx.

The Hallux (first toe) has three synovial joints.

- Tarsometatarsae joint - situated between the medial cuneïforme bone and the first metatarsal, it does not allow a lot of movement.

- Metatarsophalangeal joint - connects the first metatarsal and the first proximal phalanx. The joint allows flexion and extension of the first toe and a small ab- and adduction towards the centre of the second toe. It is also reinforced by ligaments (lig. metatarsophalangae collateralia and lig. Metatarsophalangae plantaria).

- Interphalangae joint - connection between the two phalanges of the first toe. This joint only allows flexion and extension and it is also reinforced by ligaments (lig. Interphalangae collateralia and lig. Interphalangae plantaris).

Two sesamoid bones articulate with the first metatarsal bone. These sesamoid bones:

- Protect the tendons of Flexor Hallucis Brevis FHB (embedded in the tendon of the FHB muscle)

- Main function helping FHB generate more force by extending its levers.

Muscles acting on joint:

M. tibialis anterior, M. extensor hallucis longus, M. peroneus longus, M. flexor hallucis longus, M.extensor Hallucis Brevis, M. abductor hallucis, M. flexor hallucis brevis, M. adductor hallucis, M. interossei dorsales I, aponeurosis plantaris. [10][11]

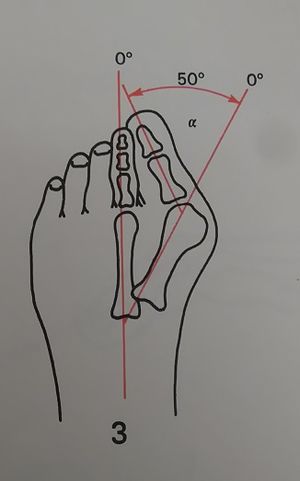

Hallux Valgus Angle

- The angle created between the lines that longitudinally bisect the proximal phalanx and the first metatarsal

- Less than 15° is considered normal. Angles of 20° and greater are considered abnormal. An angle of 45-50° is considered severe.

Epidemiology & Etiology[edit | edit source]

Etiology is not well established - certain factors have been considered to play a role in the development of hallux valgus;

- Gender (10x more frequent in women)

- Footwear (tight pointed shoes) Wearing tight shoes and/or heeled shoes between 20 and 39 years of age can be crucial in the development of hallux valgus in later years.

- Congenital deformity or predisposition

- Chronic achilles tightness

- Severe flatfoot

- Hypermobility of the first metatarsocunieform joint

- Systemic disease

- Possible that abnormal muscle insertions are partly responsible for hallux valgus

- Hallux valgus is also associated with hip and knee OA and is inversely associated with a higher BMI. [12][13][14][15][16]

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

In this foot deformity:

- Distal end of the first metatarsal drifts medially and the proximal phalanx deviates laterally.

- First MTP becomes subluxed, leading to a lateral deviation of the hallux and medial displacement of the distal end of the first metatarsal

- Bony enlargement of the first metatarsal head [2].

Mechanism behind this hallux valgus formation

- Starts with the stretching of the abductor hallucis muscle (for example as a result of wearing tight shoes).

- Base of the first proximal phalanx (PP) starts to lateralise and abducts.

- During gait, the forefoot is turned into pronation, which stretches the medial collateral ligament and the capsular structures of the first MTP joint.

- First MTP joint consists of multiple bones, ligaments, sesamoid bones and nearby muscles, all influencing other structures as they move or stretch.

- Once a threshold degree of valgus of the first PP is reached, the first metatarsal bone starts his way into a varus position.

- Hallux is pushed into a valgus position.

- Capsule gets weaker and the abductor hallucis tendon turns into a flexor of the hallux.

- As the condition progresses multiple muscles tend to worsen the situation as their axis of pull is lateralized.

As a bunion appears, friction is raised when shoes are worn.

- There may be irritation of the MCL ligament of the first MTP joint, which leads to inflammation and calcification of the joint.

- This worsens the pain and bunion size.

- In an early stage, this leads to tenderness of the bunion due to footwear.

- The skin over the bunion is hard, warm and red. Later on, the patient may have other complaints due to osteoarthritis.

- The bunion keeps moving medially and the pain gets worse. [6] [17]

A common problem in people with hallux valgus (pre-operative), is one or more disorders in their gait pattern due to the deformity of the first metatarsophalangeal joint.

Dysfunctions that may be present:

- Gait deviations in the midstance (middle stage) and the propulsion phase (late stance). As the bodyweight moves forward on a foot on the ground, the patient will tend to keep his weight on the lateral border of the foot. This leads to a lateral and posterior weight shift

- Patient has also a pronation deformity

- The patient is unable to supinate his / her foot and will tend to keep his body weight on the lateral border of the foot which results in a late heel rise

- The period of single-limb support will be diminished [17]

When a physical examination is executed, the following indications could be present:

- Lateral deviation of the MTP joint

- Swelling of first MTP joint

- Shortening of flexor hallucis brevis muscle

- Tenderness of hallux

- Weakness of hallux abductor muscles [17]

- Pain (primary symptom) [7]

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

Radiographs - used to determine the Hallux Valgus Angle (The angle created between the lines that longitudinally bisect the proximal phalanx and the first metatarsal)

- Angle is greater than 15°, hallux valgus is diagnosed[1].

- Angle of 45-50° is considered serious.

- The degree of displacement of the sesamoids and the level of osteoarthritic change within the first MTP joint should be considered as well.[2]

It is not always possible or necessary to take radiographs to determine the severity of hallux valgus. Therefore, the Manchester scale was developed [2].

- The Manchester scale consists of standardized photographs of four types of hallux valgus: none, mild, moderate and severe. Research has shown that this scale is reliable in terms of both re-test and inter-tester reliability (kappa values of 0.77 and 0.86).

- In the study by Roddy et al (2007) [18], the authors developed a tool that consists of five photographs instead of four. Each photograph had a hallux valgus angle increased with 15°. This tool had a good retest reliability (kappa = 0.82) and is also a good tool to use to determine hallux valgus severity [18]. Both scales (the four-level classification or dichotomised scale) can be used to determine the severity of hallux valgus[5].

Physical examination should be performed with the patient both seated and standing. Take note of:

- Deformity during weight bearing (generally accentuated).

- Presence of pes planus and/or contracture of the Achilles tendon

- Height of the longitudinal arch and hallux, with its relation to the lesser toes [7].

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Hallux valgus can be confused with other diseases or injuries during diagnosis. In the early stages, the redness and pain can be confused with an inflammation, infection or gout of the first MTP joint.

- Gout Pain suddenly appears while onset is gradual with hallux valgus. As well, semi uric acid level can be tested to differentiate between the two (since it is increased in patients with gout).

- Hallux Rigidus can be confused with hallux valgus

- Septic arthritis i(red and swollen).

- Turf toe can be confused with hallux valgus. [19][20][21][22][23]

- Arthropathy[24]Surgical or traumatic

Management / Interventions[edit | edit source]

Non-operative treatment[edit | edit source]

Prevention[edit | edit source]

A hereditary factor or predisposition (for example as a result of a generalized ligamentous laxity) is not preventable but other things are. For example, wearing shoes that fit properly (not too tight) and avoiding high heels can be important factors in preventing hallux valgus.[25]

Treatment[edit | edit source]

The first treatment option is non-operative care:

- Adjustment of footwear to help in eliminating friction at the level of the medial eminence (bunion) e.g., patients should be provided of a shoe with a wider and deeper toe box

- The condition of pes planus may be helped by an orthosis. Severe pes planus can lead to a recurrence of hallux valgus following surgery.

- Achilles tendon contracture may require stretching or even lengthening [7]

This type of treatment can be applied in the early stage when the secondary contractures of the soft tissues and the alterations of the articular surfaces have not become permanent [26].

Operative treatment[edit | edit source]

If non-operative treatment fails, surgery could be considered [7]. Before an operation is chosen, the severity of the hallux valgus has to be determined. In order to do that, a weight bearing plain film radiography is used.

There are about a hundred thirty one different surgical techniques. Many surgeons combine one or two techniques depending on the severity of the condition and the history of the patient. Below are a few examples of Hallux Valgus correction techniques:

- Austin/Chevron Procedure

This procedure is frequently used for mild deformities. The osteotomy is in a "V" shape, a sagittal saw is used in a medial to lateral direction inside the first metatarsal head. The loose fragment is then placed differently to correct the first metatarsal angle. The fragment is fixated with pins or screws. - Reverdin Procedure

A wedge is removed from the head of the first metatarsal head in order to get a better organisation of the articular cartilage. The wedge is situated on the dorsal side and medially based. In some cases, the surgeon decides that is necessary to rotate the articular cartilage. A screw or K-wire is used for fixation. - Scarf Procedure

When the deformity is moderate to severe, the scarf procedure is a frequently used option. The osteotomy is longitudinal, in a medial to lateral direction, inside the shaft. The capital piece is moved more to the lateral side and stabilized with two screws. - Closing Base Wedge Procedure

Base procedures are mostly used for severe deformities, so is this one. A wedge is made in the proximal metatarsal, on lateral side. When the wedge is removed, the distal part is translated to the lateral side causing the gap to close and the first metatarsal to align with the second. The minimum fixation is a bicortical screw. - Lapidus Arthrodesis

This is another option when a severe deformity is observed. By removing a piece of the articular cartilage of the medial cuneiform and the base of the first metatarsal, a fusion between the two is created. The fixation can be external, by the use of a plate or screws. - Akin Procedure

An extra correction can be constructed when a wedge is made on the medial side of the first proximal phalanx. The gap is closed by pushing the distal part to the medial side and fixating it. The similarities with the closing base wedge procedure stand out. - First Metatarsal Joint fusion in cases of midfoot instability[27]

- First Metatarsal-Phalangeal Joint Arthrodesis

The permanent elimination of motion is the reason that this procedure is one of the last options to treat a significant deformity. Most of the time, there is another component that motivates the choice of this joint destructive procedure: degenerative arthrose or an unstable joint. The proximal phalanx is correctly positioned towards the first metatarsal and is then fixated through the joint with screws, plates or crossing K-wires. [28] [29][30]

Post-operative Management[edit | edit source]

For all surgical procedures, the patient is allowed to ambulate in a post-operative shoe immediately after surgery. Patients need to wear a post-op shoe and compressive dressings from 6- 8 weeks. Long-term follow-up has shown equally positive outcomes after Chevron osteotomy for both patients both younger and older than 50 years of age.

Physiotherapy is beneficial after the corrective operation [31](research in this area needs to be developed, the availability of many surgical techniques makes it difficult to run proper clinical trials)[27].

Hallux valgus correction can be very complicated

- Especially if it was associated with instability which can be caused by bony or soft tissue abnormality.

- When combined with midfoot fusion (cases of 1st ray instability) the post-operative recovery might be challenging[27].

- Patient's beliefs should be addressed prior to the surgery because many patients get frustrated and disappointed when quick recovery is not met[27].

It is important to discuss the post-operative complications with the patient prior to the operation and explain to them that they will experience the following[27]:

- Six weeks of non-weightbearing

- Discomfort

- immobilization in a modified shoe

- Swelling might last up to six months

- You can provide the patient with reading resources to make sure they understand the surgery and its complications.

- The postoperative management shouldn't be exclusive on managing pain and restoring local mobility. It should have a wider view to assess and manage any other associated issues[27].

Key Rehabilitation Principals[27]:[edit | edit source]

Gait

Gait deficits can result from the immobilization in the modifiable shoe or plaster of Paris for at least six weeks.

- Restoring the gait, balance and the associated deficits is a key component to successful rehabilitation.

- One of the gait deficits that are often present following hallux valgus correction is when patients adopt a habit of walking on the side of their foot to avoid loading the recently operated big toe. This needs to be addressed to ensure good balance and stability and preventing other injuries in the long term[32].

To facilitate loading the first metatarsal you can use the following techniques:

- Ask your patient to walk with one foot directly in front of the other. This encourages using the tibial rotation to bring that first toe down to the floor otherwise, the patient might lose their balance and fall over.

- Manual techniques to restore soft tissue balance. Techniques such as midfoot and forefoot mobilizations, Plantar Fascia release and Achilles tendon lengthening can all be utilized.

- Foot orthoses can also be used to relieve weight-bearing stresses [17]

To address gait deficits:

- Look at gait

- Film it

- Address and correct gait

- Do it over and over and make sure your patient is confident

Strength Deficits

Weakness of the intrinsic foot muscles[33] occurs following a period of immobilization. Additionally, the patients might have had previous imbalance prior to the surgery so it's important to assess, retrain and re-educate the foot core.

The targeted muscles for strengthening are[33]:

- The intrinsics:abductor hallucis, adductor hallucis, and the flexor hallucis brevis.

- The extrinsics being the tibialis posterior and fibularis longus

Simply, ask the patient to create a dome by their foot from a seated position by pressing the toes down and shortening the foot with isometric holds. We can progress this exercise by

- Asking the patient to press the first toe down and lift the other four toes up then switch around, press the four toes down and lift the big toe up.

- Add some resistance using an exercise band (put the band underneath and press down on it while pulling the band up with both hands). This exercise is called 'foot core plus'.

- Ask the patient to do the same exercise while maintaining the dome of the foot. A further step would be to get the toes down, the first ray down, and then they can start lifting the heel, all the time, maintaining a good foot posture.

Once the patient manages to do it well in sitting, progress into these positions:

- Standing

- Standing on one foot

- Walking

- Step Up

- Step Down

A useful way to improve the control of the movement is to film the patient from behind and from the front so they can see and compare. Alternatively, they can do it in front of a mirror, have the patient walk up and down, to the mirror and back, so they can see what's happening and how are they doing it. And keep correcting them.

Improve Plantar flexion push-off

It's important to think of exercises that can improve the functional push-off rather than performing the foot exercises from sitting by progressing simple foot exercises from sitting to weight-bearing position.

Example of exercises and techniques:

- Standing over the edge of a box or a step with the exercise band and ask them to push through it.

- Walking with an exercise band underneath the toes and pulling it up. So the patient pushes their toes down into the band as they walk off, pressing down to push their foot off.

- Soft tissue work is important as well such as releasing the toe extensors as they get stiff and lose the ability to slide smoothly through the extensor retinaculum in line with the syndesmosis.

- Heel raises to strengthen the plantar flexors and if they are tight it's useful to lengthen, release and stretch them by asking the patient to stand over the edge and drop their heels down. You can put cotton wool between the toes to stretch them out.

Second toe mobility and flexibility

Assess the second toe, you want it to be sitting nicely next to the big toe. Stretching might be helpful if needed but avoid overstretching. In some cases, the toe alignment might be disturbed if the surgery wasn't successful.

This can be a challenge following the operation especially the pain that is due to scar healing (a strong bony pain would be concerning).

- Desensitising techniques to help manage pain

- TENS machine can also help with managing the pain.

- Discuss the medications with the surgeon and the patient about medication.

- Familiarize yourself with the surgical technique to avoid using a technique that could disturb the bone healing such as mobilizing a scarf osteotomy

- Sesamoid mobilization can be used - performs grade III joint mobilizations on the medial and lateral sesamoid of the affected first MPJ. One thumb is placed on the proximal aspect of the sesamoid and is used to apply a force from proximal to distal that causes the sesamoid to reach the end range of motion (distal glides). These are performed with large-amplitude rhythmic oscillations. No greater than 20° of movement of the MPJ should be allowed during the technique. [35]

The following is a suggested post-operative rehabilitation programme:

PHASE I - Pain Relief. Minimise Swelling & Injury Protection[36]

Pain is the main reason that patients seek treatment for a bunion. Inflammation is best eased using ice therapy, techniques (e.g. soft tissue massage, acupuncture, unloading taping techniques) or exercises that unload the inflamed structures. Anti-inflammatory medications may help. Orthotics can also be used to offload the bunion.

PHASE II - Restoring Normal ROM & Posture[36]

As pain and inflammation settle, the focus of treatment turns to restoring normal toe and foot joint range of motion and muscle length.

Treatment may include;

- joint mobilisation (abduction and flexion) and alignment techniques (between the first and the second metatarsal)

- massage

- muscle and joint stretches

- taping

- bunion splint or orthotic

- bunion stretch and soft tissue release. (see reference for video)[37]

PHASE III - Restore Normal Muscle Control & Strength[36]

A foot posture correction Program to assist you to regain your normal foot posture.

Dorsiflexion Strengthening with Elastic Resistance Band

The ankle dorsiflexion exercise strengthens the ankle and lower leg muscles. The patient is positioned in long-sitting. The centre of the resistance band is placed on the top of the forefoot with the toes slightly pointed. The ends of the band are either held by an assistant or secured against an immovable object (e.g. a table leg). The patient then dorsiflexes the ankle, pulling "towards their nose," working against the resistance of the band.

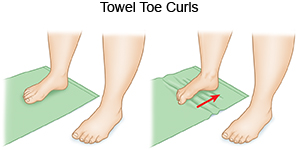

Towel curls The patient spreads out a small towel on the floor, curling his/her toes around it and pulling the towel towards them.

Toes spread out (TSO) A possible causative factor of the hallux valgus is the muscle imbalance between the abductor hallucis and the adductor hallucis. Strengthening the abductor muscle can prevent a hallux valgus and can be helpful to correct the deformity in an early stage. The toes-spread-out (TSO) exercise is an efficient way to train abductor hallucis. [38] (Level of evidence 1: 5) (Level of evidence 2: 5)

PHASE IV - Restoring Full Function

The goal of this stage of rehabilitation is to return the patient to his/her desired activities. Everyone has different demands for their feet that will determine what specific treatment goals need to be achieved.

PHASE V - Preventing a Recurrence

Bunions will deform further with no attention and bunion-associated pain has a tendency to return. The main reason is biomechanical.

In addition to muscle control, the physiotherapist should assess foot biomechanics and may recommend either a temporary off-the-shelf orthotic or refer for a custom-made orthotic. High heeled shoes and shoes with tight or angular toe boxes should be avoided.

| (Level of evidence 5)[39] | (Level of evidence 5)[40] |

Foot-wear following the operation[edit | edit source]

What should I wear after the operation? This is often an emotional topic for the patients and often, patients' and surgeons' expectations don't match at all.

- Surgeons would expect patients to wear a wide and very stable shoe.

- Important to discuss and inform the patient that their foot is going to be sensitive, swollen, and will need support for at least six months so it's important to find a suitable and nice-looking shoe that doesn't aggravate the pain.

- Ideally, find a shoe with a slightly wider toe box, a good solid heel structure that is not too high (doesn't have to be flat).

- Ask your patient: what shoes do you see yourself wearing? Or what would you like to wear? Ask the patient to bring in some of your shoes and discuss their foot position and possible effects of the shoes on their feet (Worn-out shoes may no longer be suitable because it has adapted to the shape and the weight of their previous foot posture).

- Investing in a good pair of shoes that will provide comfort and support is important (familiarize yourself with the available brands to help your patients select proper footwear).

- Friction from the scar might be an issue - advice the patient to wear Silk socks or silky stockings in the beginning and pick shoes that can give some stretch. The patient can rub the soft part of soap on their sock and shoe to improve lubrication[27].

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Mortka K, Lisiński P. Hallux valgus—a case for a physiotherapist or only for a surgeon? Literature review. Journal of physical therapy science. 2015;27(10):3303-7.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Radiographic validation of the Manchester scale for the classification of hallux valgus deformity, Menz HB et al, Rheumatology 2005;44:1061–1066(1B)

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Prevalence of hallux valgus in the general population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nix S., Smith M., Vicenzino B. Journal of Foot and Ankle Research 2010, 3:21 (1B)

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 González-Martín C, Alonso-Tajes F, Pérez-García S, Seoane-Pillado MT, Pértega-Díaz S, Couceiro-Sánchez E et al. Hallux valgus in a random population in Spain and its impact on quality of life and functionality. Rheumatol Int. 2017;37(11):1899-1907.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Validity of self-assessment of hallux valgus using the Manchester scale, Menz H et al, Musculoskeletal Disorders 2010, 11:215(1A)

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Hallux Valgus and the First Metatarsal Arch Segment: A Theoretical Biomechanical Perspective. Glasoe W et al, Phys Ther. 2010;90:110–120.(3A)

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 Decision Making in the Treatment of Hallux Valgus, Joseph T, Mroczek K. Bulletin of the NYU Hospital for Joint Diseases 2007;65(1):19-23 19 (4)

- ↑ Prevalence of hallux valgus in the general population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nix S., Smith M., Vicenzino B. Journal of Foot and Ankle Research 2010 (1a).

- ↑ Biomechanix Foot and Knee Clinic. Hallux Valgus. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L_orU3MgOVw [last accessed 08/01/17]

- ↑ SCHÜNKE et al, Prometheus lernatlas der anatomie - allgemeine anatomie und bewegungssystem (tweede druk), Georg Thieme Verlag, Stuttgart, 2005, 600p

- ↑ Internet, Bunion, (http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1235796-overview#a11), 2016-11-11.

- ↑ Hannan MT, Menz HB, Jordan JM, Cupples LA, Cheng C-H, Hsu Y-H. Hallux Valgus and Lesser Toe Deformities are Highly Heritable in Adult Men and Women: the Framingham Foot Study. Arthritis care & research. 2013;65(9):1515-1521. doi:10.1002/acr.22040. (Levels of evidence: 2B)

- ↑ Golightly YM, Hannan MT, Dufour AB, Renner JB, Jordan JM. Factors Associated with Hallux Valgus in a Community-Based Cross-Sectional Study of Adults with and without Osteoarthritis. Arthritis care & research. 2015;67(6):791-798. doi:10.1002/acr.22517. (Levels of evidence: 2A)

- ↑ Barnish MS, Barnish J. High-heeled shoes and musculoskeletal injuries: a narrative systematic review. BMJ Open. 2016;6(1):e010053. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010053.

- ↑ Menz HB, Roddy E, Marshall M, et al. Epidemiology of Shoe Wearing Patterns Over Time in Older Women: Associations With Foot Pain and Hallux Valgus. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2016;71(12):1682-1687. doi:10.1093/gerona/glw004.(Levels of evidence: 3)

- ↑ MOL, W. et STRIKWERDA, R., Compendium orthopedie, De tijdstroom, Lochum, 1977, 343p. (p.232-234).

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 Pathomechanics, Gait Deviations, and Treatment of the Rheumatoid Foot: a clinical report. Dimonte P et al. Physical therapy 1982: Vol 62(8): 1148 – 1156(5)

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Validation of a self-report instrument for assessment of hallux valgus. Roddy E et al. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2007, 15:1008-1012. (2B)

- ↑ SOBEL, E., Hallux valgus, assessment and conservative management and the role of faulty footwear, October 2001, (http://podiatrym.com/cme/oct01.pdf).

- ↑ Internet, Gout, 2016-12-08, (http://www.webmd.com/arthritis/tc/gout-topic-overview#1)

- ↑ Ashman CJ, Klecker RJ, Yu JS (2001) Forefoot pain involving the metatarsal region: differential diagnosis with MR imaging. Radiographies 21:1425–1440.

- ↑ Jeremy J., McCormick, MD, Robert B. Anderson, MD -Turf Toe: Anatomy, Diagnosis, and Treatment, Clin Sports Med. 2010 Apr;29(2):313-23 (Levels of evidence : A)

- ↑ MCRAE, R., Clinical Orthopaedic Examination, Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh, 2010, 323p (p.236-238).

- ↑ http://patient.info/doctor/hallux-rigidus

- ↑ Coşkun G, Talu B, Bek N, et al. Effects of hallux valgus deformity on rear foot position, pain, function, and quality of life of women. J Phys Ther Sci 2016; 28:781–787. (Levels of evidence: 2B)

- ↑ Hallux valgus. F. DAY, M.D., Canad. M. A. J. April 16, 1957, vol. 76 (5)

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 27.3 27.4 27.5 27.6 27.7 Simpson H. Hallux Valgus Surgery and Physiotherapy course. Physioplus 2020

- ↑ Meyr, A. et al. A pictorial review of reconstructive ankle and foot surgery: hallux abductovalgus. Journal of Radiology Case Reports. 2015; 9(6): 29-43. Geraadpleegd op 23 november 2016 via: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4638376/ fckLR(Levels of evidence: 2C)

- ↑ MOL, W. et STRIKWERDA, R., Compendium orthopedie, De tijdstroom, Lochum, 1977, 343p. (p.232-234).

- ↑ HAMBLEN, D.L. et SIMPSON, A.H.R.W., Adam’s outline of orthopaedics (14th edition), Churchill livingstone, Edinburgh, 2010, 485p. (p454-457)

- ↑ Hawson ST. Physical Therapy Post–Hallux Abducto Valgus Correction. Clinics in Podiatric Medicine and Surgery. 2014 Apr 1;31(2):309-22.

- ↑ Schuh R, Hofstaetter SG, Adams Jr SB, Pichler F, Kristen KH, Trnka HJ. Rehabilitation after hallux valgus surgery: importance of physical therapy to restore weight bearing of the first ray during the stance phase. Physical therapy. 2009 Sep 1;89(9):934-45.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Glasoe WM. Treatment of progressive first metatarsophalangeal hallux valgus deformity: a biomechanically based muscle-strengthening approach. journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy. 2016 Jul;46(7):596-605.

- ↑ Active Foot Arch Strengthening Therapeutic Exercise | Pro Physio . Available from:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G2OyCOS3c_I[last accessed 09/07/2020]

- ↑ The effects of sesamoid mobilization, flexor hallucis strengthening, and gait training on reducing pain and restoring function in individuals with hallux limitus: a clinical trial. Shamus J, Shamus E, Gugel RN, et al. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2004;80:769–780. 2B

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 http://physioworks.com.au/injuries-conditions-1/foot-bunion

- ↑ Internet, Youtube: Bunion stretch and soft tissue release; 2012-08-01, (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q5Ov6LMISvU)

- ↑ KIM, M; et al. Comparison of muscle activities of abductor hallucis and adductor hallucis between the short foot and toe-spread-out exercises in subjects with mild hallux valgus. Journal of Back and Musculoskeletal Rehabilitation. 26, 2, 163-168, Apr 2013. (levels of evidence: 5)

- ↑ Correct Toes. Bunion Stretch and Soft Tissue Release. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q5Ov6LMISvU [last accessed 08/01/17]

- ↑ Integrated Health. Hallux valgus. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zRIilSqwALU [last accessed 08/01/17]