Ewing's Sarcoma

Original Editors - from Bellarmine University's Pathophysiology of Complex Patient Problems project.

Top Contributors - Joseph Dorrell, Lisa Miville, Elaine Lonnemann, Nikhil Benhur Abburi, Lucinda hampton, Jack Tencza, Tessa Larimer, Admin, Vidya Acharya, Khloud Shreif, Kim Jackson, WikiSysop, Claire Knott, 127.0.0.1 and Wendy Walker

Introduction[edit | edit source]

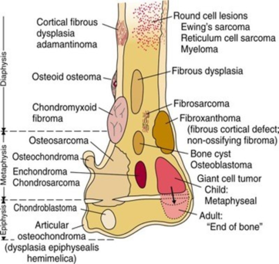

Ewing’s Sarcoma (ES) is the second most high grade malignant primary tumour of childhood and adolescence between 10-20 years of age that can arise in soft tissue or bone. [1] ESs typically arise from the bones medullary cavity, appearing as moth-eaten, destructive lesions in the shaft of long bones, and onion skin periostitis.[2] The most common sites are the pelvis, axial skeleton, and femur, but they may occur in almost any bone or soft tissue. Patients with ES within distal extremities have a better prognosis than patients having a lesion in proximal extremities.[3]

Locations:

- Lower limbs: 45%(femur most common)

- Pelvis: 20%

- Upper limbs: 13%

- Spine and ribs: 13%(sacrococcygeal)

- Skull/face: 2%[4].

Epidemiolgy[edit | edit source]

Ewing sarcoma is the second most common primary bone malignancy in adolescents and young adults, accounting for less than 5% of all soft tissue sarcomas.[3] ES usually appears in children and adolescents between 10-20 years of age, with 95% being between 4-25 years of age) and males being more affected than females (M:F 1.5:1).[2] The ES family of tumours primarily occurs in White patients. In the United States, the incidence in the Asian/Pacific Islander population is about one-half that in the White population, while the incidence in the Black population is one-ninth that in White population. [5] The incidence of Ewing’s Sarcoma has relatively been unchanged for the past 30 years and occurs 2.93 children per 1 million in the United States. [6].

Prognosis[edit | edit source]

ES prognosis is greatly affected by the presence of distant metastases at diagnosis, far more common for the pelvis (25-30%) compared to extremities (<10%). Metastases frequently going to lungs and bones. The spine is the most common site of bone metastases. Overall the 5-year survival rate is roughly 50-75% for patients with local disease only at the time of presentation.[2]

Etiology[edit | edit source]

The cell of origin of Ewing sarcoma has yet to be fully explained[3]. It has been found that 95% of Ewing's tumours are derived from a specific reciprocal translocation between chromosomes 11 and 22. The molecular oncogenesis remains unknown[7][1].

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Local pain at the affected site is usually the initial symptom[1]. The pain may be worse during exercise or at night and can be accompanied by swelling or a lump, redness, and warmth (see in this picture swelling of the left side)[8]. The pain is typically intermittent and ma progress to be more consistent.[9] Tumours that are deep inside the body such as the pelvis can be hidden from observation and inspection.

It is common to see fatigue, weight loss, decreased appetite, weakness and numbness, and/or paralysis or Urinary Incontinence (if the tumour is of spinal origin)[10]. Fever, anaemia, and leukocytosis may occur with this tumour and a palpable mass may present. The tumour may be present for months before there are any signs or symptoms. Symptoms can vary from patient to patient in terms of severity and can disappear from weeks to months at a time[4]. An injury is often what brings attention to the tumour, this is due to progressive structural bone-weakening by the disease, which can result in a fracture with minimal force. Children and adolescents with EFT can go undiagnosed until an injury from a sport or rough play requires diagnostic imaging[7]. Systemic symptoms include ESR elevation

As a physical therapist, one should be cautious when the symptoms of "growing pains" or a proposed sports injury are out of proportion or abnormal.

Radiographic features

Poorly marginated large tumours extending into adjacent soft tissues, appearance on plain radiographs is very variable, but have clearly aggressive appearance. they are permeative, have an onionskin appearance. so tissue calcification is uncommon, seen in less than 10% of cases. Occasionally they appear as Codmann triangles, thick periosteal reaction and bony expansion

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

- Osteomyelitis

- Osteosarcoma

- Metastatic disease

- Haematological malignancy

- Eosinophilic granuloma

- Neuroblastoma[2]

Systemic Involvement[edit | edit source]

Ewing's Family of Tumors are highly malignant. It most commonly spreads to the lungs, but it can also metastasize to the kidney, bone marrow, heart, adrenal gland, and other soft tissues[10]. Chemotherapy and radiation, which are most commonly used to treat EFT, have many systemic side effects including hair loss, nausea, vomiting, ulcers, and low blood cell count.[10]

Diagnostic Tests/Lab Tests/Lab Values[edit | edit source]

The diagnosing Ewing’s Sarcoma depends on full patient history, symptoms, clinical presentation and diagnostic methods as following, the first test most commonly used is X-Ray over the painful area if there is a palpable mass. An onionskin appearance is seen on X-ray.

Other tests that may be performed to rule in Ewing’s Sarcoma and determine staging are bone scans, CT scans, MRI, blood tests (elevated lactate dehydrogenase and red blood cell sedimentation rate) and biopsy for bone marrow, for example, to know whether it spreads to bone marrow or not. These tests in combination are important to find the location of the tumour and to determine if the tumour is localized or has diffused to other areas of the body to help guide treatment. Biopsy is considered the gold standard test for diagnosis of Ewing’s Sarcoma.[1][9][10]

Medical Management (current best evidence)[edit | edit source]

Depending upon the location of the tumour and metastases, doctors in many specialities help treat EFT. Medical management is considered a multidisciplinary effort which includes orthopaedic surgical oncologists, pediatric or adult medical oncologists, radiation oncologists, pathologists, and radiologists. Most patients are treated at major hospital institutions or cancer centres.[12][10][1][7]

The first line of recommended treatment is chemotherapy, also referred to as cytostatic drug therapy, which is given through an indwelling intravenous catheter. Chemotherapy medications most commonly used are vincristine (Oncovin), dactinomycin (Actinomycin D), cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan), ifosfamide (Ifex), etoposide (VePeside, VP-16), and doxorubicin (Adriamycin)[1][13][7]Chemotherapy treatment is typically performed in cycles to let the blood cell count recover. The second line of treatment, which can be done before or during chemotherapy, is a local treatment. Local treatment includes radiation and/or surgery. Surgery is used to treat localized tumour when the tumour is easily assessable. When the localized tumour is not assessable as in the pelvis or spine, surgery is not an option and radiation is used to treat the localized tumour. A detrimental side effect that can result from radiation is structural deformities in children. Surgery can also be performed to rebuild a body part or limb. As the child grows, reconstruction therapy will be necessary to lengthen the bone.[10][1][7]

Follow up intervals of 2-4 months for the first 3 years after completion of therapy is recommended for high-grade tumours such as EFT. Follow up every 6 months for year 4 and 5 and annually after that[10]. Due to the recent availability of multi-agent cytostatic approaches and local therapy, the 5-year survival rate has increased from 10% to 70%[1][14].

Immunological approaches, such as the use of cytokines (interleukins, and interferon), are still being researched.[5][15]

Physical Therapy Management (current best evidence)[edit | edit source]

Physical therapy (PT) can be beneficial for those diagnosed with EFT for many reasons and at different stages during the management process. The most common limitations for patients undergoing chemotherapy include fatigue, paralysis, or weakness, cognition, and weight loss/ gain [9]

Pre-operative PT is beneficial when feasible. Plan of care should include strengthening of the affected limb and aerobic conditioning (precaution: avoid weight bearing on an extremity or placing weight distal to the extremity in which tumour is located).[4]

Post-operative PT is essential but caution must be taken because of the impaired healing process due to chemotherapy. Precautions include: stretching the skin in the area of the incision, weight-bearing status and lab values (especially platelet count). Some general guidelines include aerobic conditioning, strengthening, continuous passive range of motion, and aquatic therapy[4]. Research suggests that knowledge on the changes occurring in muscle architecture and its impact on long-term impairments in bone sarcoma survivors after limb salvage surgery can impact rehabilitation treatment outcomes[16].

If amputation is done, it may take the child several months to learn to use a prosthetic leg or arm. A physical therapist will be able to assist in fitting and donning the prosthesis, teaching the child how to use it, and how to use necessary assistive devices. Children may also have a tissue graft, which the child needs to start moving almost immediately. Physical therapy and rehabilitation is typically recommended for six to twelve weeks post operation[7].

Ewing’s Sarcoma Case Study[edit | edit source]

Keywords

Fatigue, treatment, fever, bone pain, cancer, therapy, symptoms

Authors

Jack Tencza and Joseph Dorrell

Abstract

Ewing’s Sarcoma is the 2nd most commonly diagnosed form of primary bone cancer in children and young adults. In this example, a case study of an 18 year old Caucasian female gymnast is examined to help health care professionals identify a possible clinical case of Ewing’s Sarcoma.

Introduction

Ewing’s Sarcoma family of tumours are a group of small round cell tumours that include Ewing’s Sarcoma, Extraosseous Ewing Sarcoma, Askin Tumor, and Primitive Neuroectodermal Tumor. This cancer primarily affects children and adolescents, and most often affects soft tissue and bone. The most common sites for Ewing’s Sarcoma is the pelvis, hip, femur, tibia and fibula.

Case Presentation[edit | edit source]

Subjective :

Patient History: Pt. is an 18-year old Caucasian female who reports with a recent history of right hip pain of 5/10 during the day and 7/10 at night. She reports limping from a cartwheel at gymnastics 2 months ago. She reports that she has had night sweats with intermittent fever and general fatigue during the day. Pt. reports that she has had a recent physical examination 5 months ago with her GP who found that she was underweight. GP states this could be possibly due to female athlete triad. She notes that she has been more attentive with her diet and exercise since then. Pt. states her goal is to return to gymnastics pain-free and as soon as possible.

Medical History: Unremarkable

Objective-: Physical Examination Tests and Measures

Observation/ Palpation: Pt. has to pinpoint tenderness around R ASIS, and notes pain with R weight shifting

Lumbar ROM

Lumbar Flexion 65

Lumbar Extension 35

Lumbar Side bend 20

Lumbar Rotation 30

Hip ROM Right Left

Hip Flexion 85 130

Hip Extension 15 30

Hip IR 20 40

Hip ER 25 40

Hip ABD 25 45

MMT

L Hip 5/5 in all planes

R Hip 4/5 in all planes (pain)

UE ROM: WNL

UE MMT: WNL

Neurovascular: decreased sensation along R lateral thigh

Special Tests:

FABER - Negative

Scour Test - Positive

Anterior Labral Tear - Negative

Impingement Test - Positive

Clinical Impression

Examination findings show decreased ROM and weakness of the R hip with palpable pinpoint pain, tenderness, and warmth. No other musculoskeletal abnormalities found to be present. Working diagnosis of female athlete triad and hip impingement. Targeted interventions include strengthening the R hip musculature, improving R hip ROM in all planes, manual therapy to decrease pain and improve function, and modalities for pain relief.

Intervention

Hip AROM/ PROM exercises

Standing hip flexion, extension, abduction, IR and ER resistance exercises

Wall slides & standing squats

Hip long axis traction

Outcomes

Over a period of 5 visits, pt’s s/s did not improve. the Pain intensified to a 7/10 during the day and an 8/10 at night. PT then determined that pt needed to be referred out for imaging of the hip. Pt went to MD and received X-Ray which indicated a possible tumour of the pelvis. Blood tests indicated elevated lactate dehydrogenase and red blood cell sedimentation rate. MD referred to Oncologist for a biopsy which confirmed an Ewing’s Sarcoma of the pelvis. Pt received chemotherapy and radiation.

Discussion

Ewing’s Sarcoma is a malignant bone tumour which in this case affects a female, which is not as common as a male. In this case, the pt. demonstrated constitutional signs and symptoms including night sweats, weakness, fatigue, intermittent fever and increased pain at night which could indicate a systemic problem. Physical therapists should be aware that Ewing’s Sarcoma can mimic musculoskeletal signs and symptoms which can make it difficult to diagnosis. It is imperative to monitor the patient and refer out to patient’s MD when appropriate to prevent further metastasis of the tumour. The pelvic and hip region is the most common area affected by Ewing’s Sarcoma and can be difficult to observe and palpate due to its location. In this case the pt did not improve upon multiple visits which would indicate it is not a musculoskeletal pathology and the pt. was referred to her primary care provider for further testing.

Related Pages[edit | edit source]

A case report, Ewing's sarcoma of the ilium mimicking inflammatory arthritis of the hip.

National Organization for Rare Disorders.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 Paulussen, Michael. Frohlich, Brigit, Jurgens, Herbert. Ewing Tumour: Incidence, Prognosis, and Treatment Options. Pediatric Drugs 2001; 3(12); 899-913.(accessed 28 Feb 2011).

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Radiopedia Ewing sarcoma Available:https://radiopaedia.org/articles/ewing-sarcoma?lang=gb (accessed 27.12.2023)

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Durer S, Shaikh H. Ewing sarcoma.Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559183/(accessed 267.1.2023)

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Ewing sarcoma. Bone Cancer Research Trust. Accessed April 5, 2017.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Burningham Z, Hashibe M, Spector L, Schiffman JD. The epidemiology of sarcoma. Clinical sarcoma research. 2012 Dec 1;2(1):14.

- ↑ Ewing’s SarcomaTreatment. National Cancer Institute. https://www.cancer.gov/types/bone/hp/ewing-treatment-pdq#link/_153_toc.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 Goodman, Boissonnault, Fuller. Pathology: Implications for the Physical Therapist. Pennsylvania: Saunders, 2003.

- ↑ Medline Plus. Ewing’s Sarcoma. http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/001302.htm (accessed Feb 2011).

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Elaine Lonnemann’s Powerpoint, Oncology. Pathophysiology of Complex Patient Problems. Bellarmine University 2011.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 10.6 Gerrand C, Athanasou N, Brennan B, Grimer R, Judson I, Morland B, Peake D, Seddon B, Whelan J. UK guidelines for the management of bone sarcomas. Clinical Sarcoma Research. 2016 Dec 1;6(1):7.

- ↑ nabil ebraheimEwing's Sarcoma, Briefly - Everything You Need To Know - Dr. Nabil EbraheimAvailablehttps://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jb25_TFxAmIAccessed on 27/7/2020

- ↑ Bouaoud J, Temam S, Cozic N, Galmiche‐Rolland L, Belhous K, Kolb F, Bidault F, Bolle S, Dumont S, Laurence V, Plantaz D. Ewing’s Sarcoma of the Head and Neck: Margins are not just for surgeons. Cancer medicine. 2018 Dec;7(12):5879-88.

- ↑ Karosas AO. Ewing’s sarcoma. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy. 2010 Oct 1;67(19):1599-605.

- ↑ Goodman C, Snyder T. Differential Diagnosis for Physical Therapists: Screening for Referral. St. Louis, MO: Saunders Elsevier: 2007

- ↑ Yu H, Ge Y, Guo L, Huang L. Potential approaches to the treatment of Ewing's sarcoma. Oncotarget. 2017 Jan 17;8(3):5523.

- ↑ Nelson CM, Marchese V, Rock K, Henshaw RM, Addison O. Alterations in muscle architecture: A review of the relevance to individuals after limb salvage surgery for bone sarcoma. Frontiers in Pediatrics. 2020;8.

- ↑ Joseph Dorrell. Physiopedia Ewing's Sarcoma PT Management. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FRcrAieE_TA[last accessed 25/7/2020]