Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS): Difference between revisions

Kim Jackson (talk | contribs) (Updated CRPS guidelines (2nd edition)) |

No edit summary |

||

| (36 intermediate revisions by 4 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

<div class="editorbox"> | <div class="editorbox"> | ||

'''Original Editors ''' - [[User:Katelyn Koeninger|Katelyn Koeninger]] and [[User:Kristen Storrie|Kristen Storrie]] [[Pathophysiology of Complex Patient Problems|from Bellarmine University's | '''Original Editors ''' - [[User:Katelyn Koeninger|Katelyn Koeninger]] and [[User:Kristen Storrie|Kristen Storrie]] [[Pathophysiology of Complex Patient Problems|from Bellarmine University's Pathophysiology of Complex Patient Problems project]] and [[User:Yves Hubar|Yves Hubar]] | ||

'''Top Contributors''' {{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}} | |||

</div> | |||

== Introduction == | == Introduction == | ||

<u>C</u>omplex <u>R</u>egional <u>P</u>ain <u>S</u>yndrome (CRPS) is a term for a complex pain disorder characterised by continuing (spontaneous and/or evoked) regional pain that is seemingly disproportionate in time or degree to the usual course of any known trauma or lesion. <ref name=":33" /> Specific clinical features include [[allodynia]], hyperalgesia, sudomotor and vasomotor abnormalities, and trophic changes. | |||

CRPS has a multifactorial pathophysiology involving pain dysregulation in the [[Sympathetic Nervous System|sympathetic]] and [[Central Nervous System Pathways|central nervous systems]], and possible genetic, inflammatory, and psychological factors. | |||

= | Many names have been used to describe this syndrome such as; Reflex Sympathetic Dystrophy, causalgia, algodystrophy, Sudeck’s atrophy, neurodystrophy and post-traumatic dystrophy. To standardise the nomenclature, the name complex regional pain syndrome was adopted in 1995 by the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP).<ref name=":2">Tran Q. [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20054678/ Treatment of complex regional pain syndrome: a review of the evidence.] Can J Anesth. 2010 Feb;57(2):149-66.</ref> | ||

CRPS | == Classification and Phenotypes == | ||

CRPS is commonly subdivided into '''Type I''' and '''Type II''' CRPS. Type I occurs in the absence of major nerve damage (minor nerve damage may be present), while Type II occurs following major nerve damage.<ref name=":0">Dey DD, Schwartzman RJ. [https://www.statpearls.com/articlelibrary/viewarticle/19793/ Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (Reflex Sympathetic Dystrophy).] StatPearls;2012:07-6. </ref> Despite this distinction, there is a large overlap in clinical features and the primary diagnostic criteria are identical, and the classification therefore may have little clinical importance.<ref name=":33" /> <ref name=":3">Baron R, Wasner G. [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11252145/ Complex regional pain syndromes.] Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2001 Apr;5(2):114-23. </ref><ref name=":26">O'Connell NE, Wand BM, McAuley J, Marston L, Moseley GL. [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23633371/ Interventions for treating pain and disability in adults with complex regional pain syndrome.] Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 Apr 30;2013(4):CD009416. </ref><ref name=":8">Wasner G, Schattschneider J, Heckmann K, Maier C, Baron R. [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11222458/ Vascular abnormalities in reflex sympathetic dystrophy (CRPS I): mechanisms and diagnostic value.] Brain. 2001 Mar;124(Pt 3):587-99. </ref><ref name=":9">Jänig W, Baron R. [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12269546/ Complex regional pain syndrome is a disease of the central nervous system.] Clin Auton Res. 2002 Jun;12(3):150-64. </ref> | |||

Three stages (stage I - acute up to 3 months, stage II - dystrophic 3-6- months after onset, stage III - atrophic > 6 months) of CRPS progression have been proposed by Bonica in the past, but the existence of these stages has been suggested as unsubstantiated. <ref>[https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11790474/ Bruehl S, Harden RN, Galer BS, Saltz S, Backonja M, Stanton-Hicks M. Complex regional pain syndrome: are there distinct subtypes and sequential stages of the syndrome?] Pain. 2002 Jan;95(1-2):119-24. </ref><ref>Bruehl S, Harden RN, Galer BS, Saltz S, Backonja M, Stanton-Hicks M. [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11790474/ Complex regional pain syndrome: are there distinct subtypes and sequential stages of the syndrome?] Pain. 2002 Jan;95(1-2):119-24.</ref> It is however possible for CRPS subtypes to evolve over time, currently referred to as "'''warm CRPS"''' (warm, red, dry and oedematous extremity, inflammatory phenotype) and "'''cold CRPS"''' (cold, blue or pale, sweaty and less oedematous, central phenotype). <ref>Bruehl S, Maihöfner C, Stanton-Hicks M, Perez RS, Vatine JJ, Brunner F, Birklein F, Schlereth T, Mackey S, Mailis-Gagnon A, Livshitz A, Harden RN. [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27023422/ Complex regional pain syndrome: evidence for warm and cold subtypes in a large prospective clinical sample.] Pain. 2016 Aug;157(8):1674-81.</ref> Both of these subtypes present with comparable pain intensity. Warm CRPS is by far the most common in early CRPS, and cold CRPS tends to have a worse prognosis and more persistent symptomatology.<ref name=":33" /> | |||

[ | Dimova and associates <ref>Dimova V, Herrnberger MS, Escolano-Lozano F, Rittner HL, Vlckova E, Sommer C, Maihöfner C, Birklein F. Clin[https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31874923/ ical phenotypes and classification algorithm for complex regional pain syndrome.] Neurology. 2020 Jan 28;94(4):e357-e367. </ref>recentrly proposed another classification based on the findings of the neurological examination. The first group of patients presents with a central phenotype, with motor signs, allodynia, and glove/stocking-like sensory deficits. The second cluster represents a pheripheral inflammation phenotype, involving edema, skin color changes, skin temperature changes, sweating, and trophic changes. The third group has a mixed presentation. | ||

CRPS | As noted from above, although classification for CRPS shows some variability, there is agreement on mechanisms of central and inflammatory origin. Further research is needed to reach clusters that lead to valid and effective treatment decisions. | ||

== Epidemiology == | |||

< | === '''Incidence and Prevalence''' === | ||

CRPS incidence appears to vary according to global location. For example, studies show that Minnesota has an incidence of 5.46 per 100,000 person-years for CRPS type I and 0.82 per 100,000 person-years for CRPS type II, whilst the Netherlands in 2006 had 26.2 cases per 100,000 person-years. Research shows that CRPS is more common in females than males, with a ratio of 3.5:1.<ref name="goebel">Goebel A. [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21712368/ Complex regional pain syndrome in adults.] Rheumatology (Oxford) 2011 Oct;50(10):1739-50.</ref> CRPS can affect people of all ages, including children as young as three years old and adults as old as 75 years, but typically is most prevalent in the mid-thirties. CRPS Type I occurs in 5% of all traumatic injuries, with 91% of all CRPS cases occurring after surgery.<ref name="turner">Turner-Stokes L, Goebel A. [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22268318/ Complex regional pain syndrome in adults: concise guidance.] Clin Med (Lond) 2011 Dec;11(6):596-600.</ref> | |||

''' | === '''Location''' === | ||

The location of CRPS varies from person to person, mostly affecting the extremities, occurring slightly more in the lower extremities (+/- 60%) than in the upper extremities (+/- 40%). It can also appear unilaterally or bilaterally.<ref name=":6">Sumitani M, Yasunaga H, Uchida K, Horiguchi H, Nakamura M, Ohe K, Fushimi K, Matsuda S, Yamada Y. [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24369418/ Perioperative factors affecting the occurrence of acute complex regional pain syndrome following limb bone fracture surgery: data from the Japanese Diagnosis Procedure Combination database.] Rheumatology (Oxford). 2014 Jul;53(7):1186-93. </ref> | |||

== | === '''Prognosis''' === | ||

Approximately 15% of early CRPS (up to 6-18 months duration) fail to recover and early onset of cold CRPS predicts poor recovery.<ref name=":33" /> | |||

== Aetiology == | |||

Complex regional pain syndrome can develop after different types of injuries, such as | Complex regional pain syndrome can develop after the occurrence of different types of injuries, such as: | ||

* | *Minor soft tissue trauma (sprains) | ||

*Surgeries | *Surgeries | ||

*Fractures | *[[Fracture|Fractures]], especially following immobilisation | ||

*Contusions | *Contusions | ||

*Crush injuries | *Crush injuries | ||

| Line 39: | Line 43: | ||

*[[Stroke]] | *[[Stroke]] | ||

The onset is mostly associated with a trauma, immobilisation, injections, or surgery, but there is no relation between the grade of severity of the initial injury and the following syndrome. In 7% of cases there is no injury or surgery preceding the onset of CRPS. | |||

A study found that excessive baseline pain (>5/10) in the week following wrist fracture surgery increases the risk of developing CRPS. <ref>Moseley GL, Herbert RD, Parsons T, Lucas S, Van Hilten JJ, Marinus J. Intense pain soon after wrist fracture strongly predicts who will develop complex regional pain syndrome: prospective cohort study. The Journal of Pain. 2014 Jan 1;15(1):16-23.</ref> A stressful life and other psychological factors may be potential risk factors that impact the severity of symptoms in CRPS. <ref name=":7">Raja SN, Grabow TS. [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11981168/ Complex regional pain syndrome I (reflex sympathetic dystrophy).] Anesthesiology. 2002 May;96(5):1254-60. </ref>There is however no compelling evidence that psychiatric disorders contribute to the development of CRPS. <ref name=":33" /> | |||

== Pathophysiology == | |||

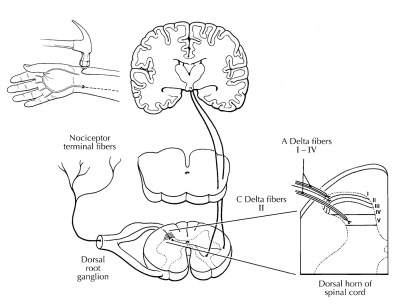

[[Image:Teasdall et al-2.jpg|right|400px]] | |||

Various mechanisms are at play in the development and maintenance of CRPS, including nerve injury, central and peripheral sensitisation, altered sympathetic function, inflammatory and immune factors, brain changes, genetic factors and psychological factors.<ref>Bruehl S. [https://rsds.insctest1.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/CRPS-Dr.-Stephen-Bruehl.pdf Complex regional pain syndrome.] Bmj. 2015 Jul 29;351.</ref> Little is however known about how these mechanisms interact and it is likely that the relative contribution of each mechanism varies between patients. <ref name=":5">Wen B, Pan Y, Cheng J, Xu L, Xu J. [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37701560/ The Role of Neuroinflammation in Complex Regional Pain Syndrome: A Comprehensive Review.] J Pain Res. 2023 Sep 6;16:3061-3073.</ref> | |||

CRPS | CRPS usually follows trauma/surgery, and likely starts with normal peripheral nociceptive stimulation. Enhanced, altered and ongoing nociception can then lead to [[Peripheral Sensitisation|peripheral]] and [http://www.physio-pedia.com/Central_sensitisation central sensitisation] (CS), with the latter regarded as a prominent mechanism underlying CRPS.<ref name=":3" /><ref>Shipton E. [https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Complex-regional-pain-syndrome-%E2%80%93-Mechanisms%2C-and-Shipton/608d7751cf116f8167f905f451e020b8c14900a6 Complex regional pain syndrome – Mechanisms, diagnosis, and management.] Curr Anaesth Crit Care. 2009; 20:209-14. </ref> | ||

Sustained neuroinflammation has lately received attention as a key factor in the initiation and perpetuation of CRPS. <ref name=":5" /> Neuropeptides mediate the enhanced neurogenic inflammation and pain; they may activate microglia and astrocytes, resulting in a cascade of events that sensitise neurons and impact synaptic plasticity. <ref name=":5" /> Upregulated cytokines, secreted by keratinocytes, exacerbate this phenomenon. <ref name=":5" /> Immune cells may also modulate neuronal activity by releasing immunomodulatory factors. <ref name=":5" /> | |||

Psychological factors could maintain CRPS by their impact on catecholamine release and kinesiophobia. The central and peripheral nervous systems are connected through neural and chemical pathways, and can have direct control over the autonomic nervous system. It is for this reason that there can be changes in vasomotor and sudomotor responses without any impairment in the peripheral nervous system. For a more detailed review of the underlying mechanisms at play, see this [https://rsds.insctest1.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/CRPS-Dr.-Stephen-Bruehl.pdf article] by Bruehl (2015). | |||

Treatment approaches are aimed at normalising afferent inputs and reversing secondary changes associated with immobilisation. | |||

< | '''Figure 1.''' ''Nociceptive (painful) information is relayed through the dorsal horn of the spinal cord for processing and modulation before cortical evaluation.'' <ref>Teasdall R, Smith BP, Koman LA. [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15062588/ Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (reflex sympathetic dystrophy).] Clin Sports Med. 2004 Jan;23(1):145-55. </ref> | ||

'''Video below:''' more on the pathophysiology underlying CRPS.<br> | |||

| | {{#ev:youtube|v=l_yWmYcNFas|250}} | ||

| | |||

== Clinical Presentation == | |||

CRPS is clinically characterised by sensory, autonomic, and motor disturbances. The table below shows an overview of these characteristics. <ref name=":2" /> <ref name=":3" /> <ref name=":10">Juottonen K, Gockel M, Silén T, Hurri H, Hari R, Forss N. [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12127033/ Altered central sensorimotor processing in patients with complex regional pain syndrome.] Pain. 2002 Aug;98(3):315-323. </ref> <ref name=":8" /> <ref name=":9" /> <ref>Galer BS, Henderson J, Perander J, Jensen MP. [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11027911/ Course of symptoms and quality of life measurement in Complex Regional Pain Syndrome: a pilot survey.] J Pain Symptom Manage. 2000 Oct;20(4):286-92. </ref> | |||

{| class="wikitable" | |||

|+Features of CRPS | |||

!'''Sensory disturbances''' | |||

![[Allodynia]] and hyperalgesia | |||

Hypoesthesia; Strange, disfigured or dislocated feeling in the limb<ref name="goebel" /> | |||

|- | |- | ||

|'''Autonomic and inflammatory components''' | |||

|Swelling and oedema<ref name="goebel" /> | |||

Hyperhidrosis; changes in sweating | |||

Abnormal skin blood flow | |||

Temperature changes<ref name="goebel" /> | |||

Colour changes (redness or pale) | |||

|- | |- | ||

| ''' | |'''Trophic changes''' | ||

| | |Thick, brittle, or rigid nails | ||

Increased/decreased hair growth | |||

Thin, glossy, clammy skin<ref name="goebel" /> | |||

Osteopenia (chronic stage) | |||

|- | |- | ||

| ''' | |'''Motor dysfunction''' | ||

| | |Weakness of multiple muscles and atrophy <ref name="goebel" /> | ||

Inability to initiate movement of the extremity | |||

Stiffness and reduced ROM | |||

Tremor or dystonia | |||

|- | |- | ||

| ''' | |'''Pain''' | ||

| | |Burning, deep, dull | ||

Disproportionate | |||

Spontaneous and/or triggered by movement, noise, pressure on joint | |||

Pain may not be present in 7% of CRPS patients<ref name="goebel" /> | |||

|} | |} | ||

<br>Symptoms can spread beyond the area of the lesioned nerve in Type II. Ongoing neurogenic inflammation, vasomotor dysfunction, central sensitisation and maladaptive neuroplasticity contribute to the clinical phenotype of CRPS. <ref name=":8" /> <ref name=":6" /> | |||

== Associated Co-morbidities == | == Associated Co-morbidities == | ||

CRPS may also be associated with: | CRPS may also be associated with: | ||

* | *Impaired microcirculation <ref name=":11">Groeneweg G, Huygen F, Coderre T, Zijlstra F. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2758836/ Regulation of peripheral blood flow in Complex Regional Pain Syndrome: clinical implication for symptomatic relief and pain management.] BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2009;10:116.</ref> | ||

*[[Asthma]]<ref name="goebel" /> | *[[Asthma]] <ref name="goebel" /> | ||

* | *[[Fracture|Fractures]] <ref name="Hooshmand">Hooshmand H, Phillips E. [https://www.rsdrx.com/Spread_of_CRPS.pdf Spread of complex regional pain syndrome.] Available from: https://www.rsdrx.com/Spread_of_CRPS.pdf [accessed 5/7/2023]</ref> | ||

*[[Cellulitis]]<ref | *[[Cellulitis]] <ref>Goebel A. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4590068/ Current Concepts in Adult CRPS. Rev Pain.] 2011 Jun; 5(2): 3–11.</ref> | ||

*Conversion Disorder <ref>Popkirov S, Hoeritzauer I, Colvin L, Carson AJ, Stone J. [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30355604/ Complex regional pain syndrome and functional neurological disorders - time for reconciliation.] J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2019 May;90(5):608-14. </ref> | |||

*Conversion Disorder<ref | |||

*[[Depression]]/Anxiety | *[[Depression]]/Anxiety | ||

* | *Lymphedema <ref name=":11" /> | ||

* | *Malignancy <ref>Mekhail N, Kapural L. [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10998738/ Complex regional pain syndrome type I in cancer patients.] Curr Rev Pain. 2000;4(3):227-33. </ref> | ||

*[[Migraine Headache|Migraines]] <ref name="goebel" /> | |||

*[[Migraine Headache|Migraines]]<ref name="goebel | *[[Osteoporosis]] <ref name="goebel" /><ref name="Hooshmand" /> | ||

*Autoimmune dysfunction <ref>Dirckx M, Schreurs M, de Mos M, Stronks D, Huygen F. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4337272/ The Prevalence of Autoantibodies in Complex Regional Pain Syndrome Type I.] Mediators Inflamm. 2015; 2015: 718201.</ref> | |||

*[[Osteoporosis]]<ref name="goebel" /><ref name="Hooshmand" /> | |||

* | |||

== Differential Diagnosis == | == Differential Diagnosis == | ||

Differential diagnosis includes the direct effects of the following conditions<ref> | Differential diagnosis includes the direct effects of the following conditions: <ref name="turner" /><ref>Thomson McBride AR, Barnett AJ, Livingstone JA, Atkins RM. [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18716503/ Complex regional pain syndrome (type 1): a comparison of 2 diagnostic criteria methods.] Clin J Pain. 2008 Sep;24(7):637-40. </ref> | ||

*Bony or soft tissue injury | *Bony or soft tissue injury | ||

*Peripheral [https://physio-pedia.com/Neuropathies# neuropathy], nerve lesions | *Peripheral [https://physio-pedia.com/Neuropathies# neuropathy], nerve lesions | ||

*Arthritis | *[[Arthritis]] | ||

*Infection | *Infection | ||

*[http://www.physio-pedia.com/Compartment_Syndrome Compartment syndrome] | *[http://www.physio-pedia.com/Compartment_Syndrome Compartment syndrome] | ||

*Arterial insufficiency | *Arterial insufficiency | ||

*Raynaud’s Disease | *[[Raynaud's Phenomenon|Raynaud’s Disease]] | ||

*Lymphatic or venous obstruction | *Lymphatic or venous obstruction (eg. DVT) | ||

*[http://www.physio-pedia.com/Thoracic_Outlet_Syndrome Thoracic Outlet Syndrome (TOS)] | *[http://www.physio-pedia.com/Thoracic_Outlet_Syndrome Thoracic Outlet Syndrome (TOS)] | ||

*Gardner-Diamond Syndrome | *Gardner-Diamond Syndrome | ||

| Line 241: | Line 135: | ||

*Self-harm or malingering | *Self-harm or malingering | ||

*[[Cellulitis]] | *[[Cellulitis]] | ||

* | *Undiagnosed fracture | ||

== Diagnostic Procedures == | == Diagnostic Procedures == | ||

There are 4 diagnostic tools for CRPS in adult populations. These include the Veldman criteria, IASP criteria, Budapest Criteria, and Budapest Research Criteria.<ref name=":1" /> | CRPS diagnosis is mainly based on patient history, clinical examination, and supportive investigations. | ||

There are 4 diagnostic tools for CRPS in adult populations. These include the Veldman criteria, IASP criteria, Budapest Criteria, and Budapest Research Criteria.<ref name=":1" /> | |||

=== The Budapest Criteria === | === The Budapest Criteria === | ||

The Budapest criteria (also known as the IASP and explicitly endorsed by the IASP) has been developed for the diagnosis of CRPS, but improvements still need to be made.<ref> | The Budapest criteria (also known as the IASP criteria and explicitly endorsed by the IASP) has been developed for the diagnosis of CRPS, but improvements still need to be made. <ref name=":12">Harden NR, Bruehl S, Perez RSGM, Birklein F, Marinus J, Maihofner C, Lubenow T, Buvanendran A, Mackey S, Graciosa J, Mogilevski M, Ramsden C, Chont M, Vatine JJ. [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20493633/ Validation of proposed diagnostic criteria (the "Budapest Criteria") for Complex Regional Pain Syndrome.] Pain. 2010 Aug;150(2):268-74. </ref><ref name=":15">Choi E, Lee PB, Nahm FS. [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23331254/ Interexaminer reliability of infrared thermography for the diagnosis of complex regional pain syndrome.] Skin Res Technol. 2013 May;19(2):189-93. </ref><ref name=":13">Harden NR. [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22424876/ The diagnosis of CRPS: are we there yet?] Pain. 2012 Jun;153(6):1142-1143. </ref> Clinical diagnostic criteria for CRPS are: <ref name=":33" /> | ||

# Continuing pain, which is disproportionate to any inciting event | |||

# Must '''report''' at least one '''symptom''' in three of the four following categories: | |||

#* ''Sensory:'' hyperalgesia and/or allodynia | |||

#* ''Vasomotor''''':''' temperature asymmetry and/or skin colour changes and/or skin colour asymmetry | |||

#* ''Sudomotor/oedema:'' oedema and /or sweating changes and/or sweating asymmetry | |||

#* ''Motor/trophic''''':''' decreased range of motion and/or motor dysfunction (weakness, tremor, dystonia) and/or trophic changes (hair, nail, skin) | |||

# Must display at least one '''sign''' at the time of '''evaluation i'''n two or more of the following categories | |||

#* ''Sensory:'' hyperalgesia (to pinprick) and/or allodynia (to light touch/pressure/joint movement) | |||

#* ''Vasomotor''''':''' evidence of temperature asymmetry and/or skin colour changes and/or skin colour asymmetry | |||

#* ''Sudomotor/oedema:'' evidence of oedema and /or sweating changes and/or sweating asymmetry | |||

#* ''Motor/trophic''''':''' evidence of decreased range of motion and/or motor dysfunction (weakness, tremor, dystonia) and/or trophic changes (hair, nail, skin) | |||

# There is no other diagnosis that better explains the signs and symptoms | |||

The Budapest Criteria have excellent diagnostic sensitivity of 99% and a moderate specificity of 68%. <ref name=":1">Mesaroli G, Hundert A, Birnie KA, Campbell F, Stinson J. [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33230004/ Screening and diagnostic tools for complex regional pain syndrome: a systematic review.] Pain. 2021 May;162(5):1295-1304.</ref> See the video below for more detail on the Budapest Criteria. | |||

{{#ev:youtube|FjZH7Fl1wLs}} | |||

<ref>Bia Education. Diagnostic criteria for CRPS. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FjZH7Fl1wLs [accessed 6/7/2023]</ref> | |||

=== Other Tests === | |||

* | * '''Infrared Thermography:''' Infrared thermography (IRT) is an effective mechanism to find significant asymmetry in temperature between both limbs by determining if the affected side of the body shows vasomotor differences in comparison to the other side. It is reported having a sensitivity of 93% and a specificity of 89%. <ref name=":16">Albazaz R, Wong YT, Homer-Vanniasinkam S. [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18346583/ Complex regional pain syndrome: a review.] Ann Vasc Surg. 2008 Mar;22(2):297-306. </ref> This test is hard to obtain so it is not often used for diagnosing of CRPS. <ref name=":15" /> <ref name=":14">Perez RS, Collins S, Marinus J, Zuurmond WW, de Lange JJ. [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17400490/ Diagnostic criteria for CRPS I: differences between patient profiles using three different diagnostic sets.] Eur J Pain. 2007 Nov;11(8):895-902. </ref><ref name=":16" /> | ||

* '''Sweat Testing:''' Determining if the patient sweats abnormally. Q-sweat is an adequate instrument to measure sweat production. The sweat samples should be taken from both sides of the body at the same time. <ref name=":3" /><ref name=":16" /> | |||

* | * '''Radiographic testing:''' Irregularities in the bone structure and osteopenia of the affected side of the body can become visible with the use of [http://www.physio-pedia.com/X-Rays X-rays]. <ref name=":3" /> <ref name=":16" /> | ||

* | * '''Three phase bone scan:''' A triple phase bone scan is the best method to rule out Type I CPRS. <ref>Cappello ZJ, Kasdan ML, Louis DS. [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22177715/ Meta-analysis of imaging techniques for the diagnosis of complex regional pain syndrome type I.] J Hand Surg Am. 2012 Feb;37(2):288-96.</ref> With the use of technetium Tc 99m-labeled bisophosphonates, an increase in bone metabolism can be shown. Higher uptake of the substance means increased bone metabolism and the body part could be affected. <ref name=":16" /> The triple-phase bone scan has the best sensitivity, NPV, and PPV compared to MRI and plain film radiographs. | ||

* '''Bone densitometry:''' An affected limb often shows less bone mineral density and a change in the content of the bone mineral. During treatment of the CPRS the state of the bone mineral will improve. So this test can also be used to determine if the patient’s treatment is effective. <ref name=":16" /> | |||

* | * '''Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI):''' [https://www.physio-pedia.com/MRI_Scans MRI scans] are useful to detect periarticular marrow oedema, soft tissue swelling and joint effusions. And in a later stage, atrophy and fibrosis of periarticular structures can be detected. But these symptoms are not exclusively signs of CRPS. <ref name=":3" /><ref name=":16" /> | ||

* | |||

== Outcome Measures == | |||

The CRPS consortium has established a list of core outcome measures to be used for patients with CRPS (referred to as COMPACT).<ref>Grieve S, Perez RS, Birklein F, Brunner F, Bruehl S, Harden N, Packham T, Gobeil F, Haigh R, Holly J, Terkelsen A. Recommendations for a first Core Outcome Measurement set for complex regional PAin syndrome Clinical sTudies (COMPACT). Pain. 2017 Jun;158(6):1083.</ref> | |||

'''Patient reported Outcome Measures:''' | |||

* [https://www.unmc.edu/centric/_documents/PROMIS-29.pdf PROMIS-29:] Assesses 7 domains (physical function, pain interference, fatigue, depression, anxiety, sleep, social participation) | |||

* [[Numeric Pain Rating Scale|NPRS]]: Numeric pain rating scale | |||

* [[Short-form McGill Pain Questionnaire]] (SF-MPQ-2): Six neuropathic items capture pain quality | |||

* [[Pain Catastrophizing Scale|Pain Catastrophising Scale]] | |||

* [[EQ-5D|EQ-5D-5L:]] Measurement of health state | |||

* [[Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire (PSEQ)|Pain Self-efficacy Questionnaire]] | |||

* CRPS symptom questions: Derived from the Budapest Criteria | |||

'''Clinical reported Outcome Measures:''' | |||

* ''CRPS Severity Score (CSS):'' Includes 8 signs and 8 symptoms that reflect the sensory, vasomotor, sudomotor/edema and motor/trophic disorders of CPRS, coded based on the history and physical examination. Extent of changes in CSS scores over time are significantly associated with changes in pain intensity, fatigue, and functional impairments. Thus, the CSS appears to be valid and sensitive to change. A change of 5 or more CSS scale points reflects a clinically-significant change. <ref name=":33" /> | |||

'''Other Outcome Measures''' (not part of COMPACT)''':''' | |||

* Various region specific functional measures can be used for either upper limb or lower limb CRPS, eg. [[Grip Strength|Grip strength]] <ref>Hotta J, Harno H, Nummenmaa L, Kalso E, Hari R, Forss N. [https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/ejp.669 Patients with complex regional pain syndrome overestimate applied force in observed hand actions.] Eur J Pain. 2015;19(9):1372-81. </ref> | |||

==== | == Examination == | ||

The diagnosis is based on the clinical presentation described above. Procedures start with taking a detailed medical history, taking into account any initiating trauma and any history of sensory, autonomic, and motor disturbances, as well as how the symptoms developed, the time frame, distribution and characteristics of pain. Assessment for any swelling, sweating, trophic and/or temperature increases, and motor abnormality in the disturbed area is important. Skin temperature differences may be helpful for diagnosis of CRPS. The original IASP criteria required only a history and subjective symptoms for a diagnosis of CRPS, but recent consensus guidelines have argued for the inclusion of objective findings. <ref name=":23">PENTLAND, B. [https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9780203989326-54/parkinsonism-dystonia-pentland Parkinsonism and dystonia.] By: Greenwood R, McMillan T, Barnes M, Ward C. (eds) Handbook of Neurological Rehabilitation. 1st ed. London: Psychology Press, 2002. </ref> | |||

= | The clinical presentation of CRPS, and the underlying mechanisms, can differ between patients and even within a patient over time - it is therefore important assess underlying pain mechanisms in order to design targeted treatment for each individual.<ref name=":33">Harden RN, McCabe CS, Goebel A, Massey M, Suvar T, Grieve S, Bruehl S. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9186375/ Complex regional pain syndrome: practical diagnostic and treatment guidelines.] Pain Medicine. 2022 May 1;23(Supplement_1):S1-53.</ref> | ||

# '''Autonomic Dysfunction:''' The majority of patients with CRPS have bilateral differences in limb temperature and the skin temperature depends of the chronicity of the disease. In the acute stages, temperature increases are often concomitant with a white or reddish colouration of the skin and swelling. where the syndrome is chronic, the temperature will decrease and is associated with a bluish tint to the skin and atrophy. <ref name=":25">Frontera W, Silver J. [https://shop.elsevier.com/books/essentials-of-physical-medicine-and-rehabilitation/frontera/978-0-323-54947-9 Essentials of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation - Musculoskeletal disorders, Pain and Rehabilitation.] Saunders Elsevier, 2002.</ref> | |||

# '''Motor Dysfunction:''' Studies have shown that approximately 70% of the patients with CRPS show muscle weakness in the affected limb, exaggerated tendon reflexes or tremor, irregular myoclonic jerks, and dystonic muscle contractions. Muscle dysfunction often coincides with a loss of range of motion in the distal joints. <ref name=":24">Sebastin SJ. [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22022040/ Complex regional pain syndrome.] Indian J Plast Surg. 2011 May;44(2):298-307. </ref> | |||

# '''Sensory Dysfunction:''' The distal ends of the extremities require attention when examining a patient with CRPS. However, common findings of regional neuropathic and motor dysfunction have shown us that it is important to broaden the examination both proximally and contralaterally. <ref name=":25" />Light touch, pinprick, temperature and vibration sensation should be assessed for a complete picture of the CRPS. <ref name=":25" /> Most assessments are interlinked, for example, when vibration sensation is highly positive, light touch should also be positive. <ref name=":25" />To help distinguish the findings of a sensory dysfunction, bilateral comparisons are made. <ref name=":24" /><ref name=":25" />Also see [[Quantitative Sensory Testing (QST)|Quantitative Sensory Testing.]] | |||

==== | == Multidisciplinary Management == | ||

= | CRPS can be very difficult to treat successfully, as it involves both central and peripheral pathophysiology, as well as frequent psychosocial components.<ref name=":33" /> This complexity of CRPS calls for an interdisciplinary approach, where the entire management team collaborates and focuses on all the relevant biopsychosocial elements. In many settings this is not feasible - in such cases a multidisciplinary approach is still very important to address the multifactorial nature of CRPS.<ref name=":33" /> Treatment of complex regional pain syndrome should be immediate, and most importantly directed toward functional restoration. Functional restoration emphasises physical activity, desensitisation and normalisation of sympathetic tone, and involves steady progression. <ref name=":33" /> | ||

< | === Treatment Overview === | ||

Despite multiple interventions being described and commonly used, the optimal management of CRPS is still under debate. The latest published evidence from Cochrane and non‐Cochrane systematic reviews of the efficacy, effectiveness, and safety interventions did not identify high‐certainty evidence for the effectiveness of any therapy for CRPS. <ref name=":18">Ferraro MC, Cashin AG, Wand BM, Smart KM, Berryman C, Marston L, Moseley GL, McAuley JH, O'Connell NE. [https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD009416.pub3/full Interventions for treating pain and disability in adults with complex regional pain syndrome‐ an overview of systematic reviews.] Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2023; 6: CD009416. </ref> This paper was the first update of the original Cochrane review in 2013. <ref name=":18" /> | |||

Nevertheless, the following table summarises treatment recommendations for CRPS. These strategies are based on the Malibu CRPS algorithm and most recent treatment guidelines.<ref name=":33" /> | |||

{| class="wikitable" | |||

|+'''CRPS treatment overview''' | |||

! | |||

!'''Description & Modalities''' | |||

!'''Team members''' | |||

|- | |||

!'''''Functional Restoration''''' | |||

! | |||

! | |||

|- | |||

|'''Phase 1:''' Activation of pre-sensorimotor cortices | |||

|[[Graded Motor Imagery|Graded motor imagery]] | |||

Visual tactile discrimination | |||

|PT/OT | |||

|- | |- | ||

| | |'''Phase 2:''' Gentle active ROM | ||

| | |Progressive AROM | ||

| | Isometric strengthening | ||

|PT | |||

|- | |- | ||

| | |'''Phase 3:''' Weight bearing | ||

| | |UL: carrying items | ||

LL: partial weight bearing | |||

|PT/OT | |||

|- | |||

|'''''Desensitisation''''' | |||

|Progressive stimulation with textures (soft to more rough) | |||

Contrast baths with progressive broadening of the temp difference | |||

|OT/PT | |||

|- | |||

|'''''Pain Management''''' | |||

|Sympathetic blocks and/or medication to allow engagement with functional restoration | |||

Functional restoration addresses pain by normalising afferent inputs and central processing | |||

|MD | |||

PT | |||

|- | |||

|'''''Edema Management''''' | |||

|Pressure garments | |||

Aquatic therapy | |||

General aerobic activity | |||

|PT/OT | |||

|- | |||

|'''''Psychological approaches''''' | |||

|CBT and exposure-based therapy if patient presents with kinesiophobia | |||

Psychotherapy if depression/anxiety is present | |||

|Psych/PT | |||

|- | |||

|'''''Secondary impairments''''' | |||

|Local muscle spasm, reactive bracing and disuse atrophy secondary to pain needs to be addressed | |||

|PT | |||

|} | |||

==== Medical Management ==== | |||

Medical management is aimed at achieving sufficient pain relief, in order to allow for rehabilitation interventions to commence and progress. Most medications used for CRPS lack high quality evidence, and most treatment regimes are extrapolated from evidence for related [[Neuropathic Pain|neuropathic]] conditions. CRPS does however differ from other neuropathic conditions in that additional circulatory, bone and inflammatory pathways are present<ref name=":33" />. Patients also present with a varying dominant mechanisms (including central sensitisation, motor abnormalities and sympathetic abnormalities), and it is therefore important to base medication prescription on reasoning regarding evident underlying mechanisms. Below is a summary of the possible medical interventions for patients with CRPS: | |||

{| class="wikitable" | |||

|+Medical interventions for CRPS<ref name=":33" /> | |||

! | |||

!'''Description''' | |||

!'''Evidence/ considerations''' | |||

|- | |||

!'''Pharmacotherapy''' | |||

! | |||

! | |||

|- | |||

|''Anti-inflammatory drugs'' | |||

|[[NSAIDs]] (esp Ketoprofen), COX-2 inhibitors, corticosteroids | |||

|Useful to address the inflammatory component of CRPS, but often not effective as [[Neurogenic Inflammation|neurogenic inflammation]] mostly dominant. Risks regarding long-term use needs to be considered | |||

|- | |||

|''Biphosponates'' | |||

|Have immune-modulatory properties and modulate bone metabolism | |||

|May help in acute stages or in selected subtypes of CRPS (where osteopenia is evident), but the evidence is lacking | |||

|- | |||

|''Cation-Channel blockers'' | |||

|Anticonvulsants (gabapentin/pregabalin) | |||

|Proven efficacy for other neuropathic pain conditions; evidence for CRPS is lacking | |||

|- | |||

|''Tricyclic drugs'' | |||

|Anti-depressants that augment descending inhibition | |||

|Effective for other neuropathic conditions; worth considering in patients with associated insomnia, depression and/or anxiety | |||

|- | |||

|''Opioids'' | |||

|Tramadol | |||

Methadone | |||

|Tolerance and long-term toxicity are important concerns, and can worsen allodynia and hyperalgesia; daily use is not recommended in CRPS - only for excruciating pain | |||

|- | |||

|''NMDA Antagonists'' | |||

|Ketamine | |||

|High risk of toxicity; IV ketamine may have positive effects on central sensitisation | |||

|- | |||

|''Alpha2-adrenergic Agonists/ Ca-channel blockers'' | |||

|Clonidine | |||

Nifedipine | |||

|Evidence is contradictory. Adverse effects can occur | |||

|- | |||

|''Calcitonin'' | |||

|Hormone produced by the thyroid | |||

|A meta-analysis demonstrated benefits of intranasal administration, but subsequent studies had conflicting results | |||

|- | |- | ||

| | |''Immune modulators'' | ||

| | |Steroids | ||

| | Immunoglobulins (IVIG) | ||

|Evidence suggests that early initiation (after trauma), followed by tapering, may be effective | |||

Steroid injections are ineffective | |||

IVIG has limited evidence | |||

|- | |- | ||

| | |'''Other''' | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | |''Topical treatment'' | ||

| | |Lidocaine | ||

| | Capsaicin | ||

|Capsaicin can be intolerably painful in the presence of hyperalgesia | |||

|- | |- | ||

| | |''Supplements'' | ||

| | |Vitamin C | ||

| | |Daily Vit C following limb fracture or surgery may prevent CRPS | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | |''Sympathetic blocks'' | ||

| | |Local anaesthetic block applied at the transverse process of C6 or L2/3 | ||

| | |High quality evidence is lacking, but may be useful for a subset of patients with prominent vasomotor dysfunction, to provide pain relief and a window of opportunity for rehabilitation techniques<ref name=":33" /><ref name=":16" /> | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | |''Spinal cord stimulations'' | ||

| | |Aims to inhibit the nociceptive pathways at the level of the dorsal column | ||

| | |Reserved for use when patients are not responding to other interventions. Safe and proven long-term effective for chronic CRPS<ref name=":33" /> | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | |''Dorsal root ganglion stimulation''<ref name=":0" /> | ||

| | |Aims to modulate nociceptive pathways at the dorsal root | ||

| | |Evidence shows reduced pain, improved quality of life and function if conservative therapy has failed<ref name=":33" /> | ||

|} | |} | ||

It is likely that medication prescription will need to be adapted over time as CRPS progresses or patients develop tolerance. The following table presents a consensus-based pharmacotherapy guide based on clinical findings in CRPS: <ref name=":33" /> | |||

{| class="wikitable" | |||

!'''Reason for inability to start/progress with rehab''' | |||

!'''Pharmacotherapy reccommendations''' | |||

|- | |||

|''Mild to moderate pain'' | |||

|Simple analgesics and/or blocks | |||

|- | |||

|''Excruciating pain'' | |||

|Opioids and/or blocks | |||

|- | |||

|''Inflammation and oedema'' | |||

|Steroids, NSAIDs, immune modulators | |||

|- | |||

|''Depression, insomnia'' | |||

|Anti-depressants | |||

|- | |||

|''Severe allodynia/hyperalgesia'' | |||

|Anticonvulsants and/or NMDA antagonists | |||

|- | |||

|''Osteopenia and trophic changes'' | |||

|Calcitonin or biphosphonates | |||

|- | |- | ||

| | |''Profound vasomotor disturbance'' | ||

|Calcium channel blockers and/or blocks | |||

|} | |} | ||

=== Physiotherapy Management === | |||

Various consensus groups have emphasised that physiotherapy is of utmost importance in restoring function in patients with CRPS.<ref name=":3" /><ref name=":33" /> Studies have shown that exercise-based physiotherapy is effective in managing pain and reducing impairment. <ref name=":33" /><ref name=":4">Lee BH, Scharff L, Sethna NF, McCarthy CF, Scott-Sutherland J, Shea AM, Sullivan P, Meier P, Zurakowski D, Masek BJ, Berde CB. [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12091866/ Physical therapy and cognitive-behavioral treatment for complex regional pain syndromes.] J Pediatr. 2002 Jul;141(1):135-40. </ref> | |||

* | Physiotherapy aims to restore function, using the following intervention strategies: | ||

*[[Graded Motor Imagery|'''Graded Motor Imagery''']] (GMI): Aims to address altered central processing by restoring the mismatch between afferent input and central representation. A meta-analysis demonstrated very good evidence for the efficacy of GMI in combination with medical management in patients with CRPS-1, with many studies indicating improvements in pain and function.<ref name=":2" /><ref name=":26" /><ref>Daly AE, Bialocerkowski AE. Does evidence support physiotherapy management of adult Complex Regional Pain Syndrome Type One? A systematic review. European Journal of Pain. 2009 Apr 1;13(4):339-53.</ref><ref name=":31">Moseley GL. [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15109523/ Graded motor imagery is effective for long-standing complex regional pain syndrome: a randomised controlled trial.] Pain. 2004 Mar;108(1-2):192-8. </ref>[[File:Mirror therapy.jpg|thumb]] | |||

*'''[[Mirror Therapy|Mirror visual feedback (MVF)]]:''' Proven to be effective in patients with CRPS-1 and for stroke patients with CRPS.<ref name=":33" /> <ref name=":17">McCabe CS, Haigh RC, Blake DR. [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18474189/ Mirror visual feedback for the treatment of complex regional pain syndrome (type 1).] Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2008 Apr;12(2):103-7.</ref><ref name=":26" />It is critical that the patient 'believes' the illusion. | |||

*'''Tactile sensory discrimination training''' <ref name=":26" /><ref name=":32">Bowering KJ, O'Connell NE, Tabor A, Catley MJ, Leake HB, Moseley GL, Stanton TR. [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23158879/ The effects of graded motor imagery and its components on chronic pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis.] J Pain. 2013 Jan;14(1):3-13. </ref> | |||

*'''Progressive strengthening:''' Starting with isometrics, and then gently progressing isotonic and resisted movements.<ref name=":26" /> | |||

*'''Education and pacing:''' Patients need to be told that both too much and too little movement can increase pain, and physiotherapists need to help patients to find a "happy medium", while guiding them towards more function.<ref name=":33" />Incorporating [[Pain Neuroscience Education (PNE)|pain neuroscience education (PNE)]] elements can help reduce kinesiophobia by explaining that pain does not signal tissue damage.<ref name=":33" /> | |||

*'''[[Flexibility]]/ROM exercises:''' Active ROM and functional movements, while maintaining good movement patterns. Bilateral movements and conscious attention to the limb should be encouraged. <ref name="goebel" />Graded exposure can help to reduce kinesiophobia. | |||

*[[Aquatherapy|'''Aquatic therapy''']]: Allows activities to be performed with decreased weight bearing on the lower extremities, which can be a tolerable way of introducing weight bearing/resistance exercises. Hydrostatic pressure also provides gentle compression around the joints which can reduce oedema.<ref name=":33" /> | |||

[[File:Mirror therapy.jpg|thumb]] | *[[Desensitization|'''Desensitisation:''']] Consist of giving stimuli of different fabrics, different pressures (light or deep), vibration, tapping, heat or cold. See OT section <ref name="goebel" /><ref name=":33" /> | ||

*[[ | *'''Gradual weight bearing:''' Exposure the affected extremity to gradually increasing weight bearing activities. Gait training should be included for lower limb CRPS. <ref name="goebel" /><ref name=":33" /><ref name=":2" /><ref name=":30">Smith TO. [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17042007/ How effective is physiotherapy in the treatment of complex regional pain syndrome type I? A review of the literature.] Musculoskeletal Care. 2005;3(4):181-200. </ref> | ||

*[[Aquatherapy|Aquatic | *[[Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (TENS)|'''TENS''']]: Evidence is lacking, but may have some benefit<ref name=":33" /> | ||

*[[ | |||

*Gradual weight bearing <ref name="goebel" /> | |||

= | |||

* '''[[Relaxation Techniques|Relaxation]] exercises:''' The efficacy of relaxation-focused interventions (such as [[Diaphragmatic Breathing Exercises|diaphragmatic breathing]]) may be impaired due to the physiological alterations associated with CRPS. <ref name=":30" /><ref name=":33" /> | |||

Physiotherapists should '''avoid''' aggressive exercises, prolonged application of ice and prolonged rest/inactivity - these can exacerbate symptoms.<ref name=":33" /> '''Massage''' lacks evidence, but may be useful in oedema management if applied carefully.<ref name=":33" /><ref name=":2" /><ref name=":26" /> | |||

Since the mechanisms underlying CRPS are often widespread, it may be beneficial to involve unaffected extremities during exercises, especially when moving the affected extremity is too painful.<ref name="Hooshmand" /> | |||

=== Occupational Therapy Management === | |||

Occupational therapists (OTs) are pivotal in the functional restoration process as experts in biopsychosocial principles and functional assessment. The role of the OT involves initial functional evaluation (including ROM, coordination, dexterity, pain, sensation and use of the extremity during ADLs), followed by various intervention strategies, including: | |||

* '''[[Graded Motor Imagery|GMI]] and [[Mirror Therapy|Mirror visual feedback]]''' | |||

* | * '''[[Desensitization|Desensitisation:]]''' Involves graded exposure to textures (from soft to more textured). Aids in normalisation of cortical organisation in CRPS patients by restoring the sensory cortex<ref name=":33" /><ref name=":29">Stanton-Hicks M, Baron R, Boas R, Gordh T, Harden N, Hendler N, Koltzenburg M, Raj P, Wilder R. [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9647459/ Complex Regional Pain Syndromes: guidelines for therapy.] Clin J Pain. 1998 Jun;14(2):155-66. </ref> | ||

* '''Oedema Management''': Using specialised garments and manual oedema mobilisation. <ref name=":33" /> | |||

* '''[[Splinting]]:''' May be indicated in severe cases to promote improved circulation to the area and to facilitate more normal positioning. Symptoms can be exacerbated by splinting and should therefore be closely monitored.<ref name=":33" /> | |||

* '''Stress loading:''' This involves active movement and compression of the affected joints, and although it may at first increase symptoms, this is usually followed by reduced pain and swelling. It consists of: <ref name=":33" /> | |||

** ''Scrubbing -'' moving the affected extremity back/forth while weight bearing through the extremity, using a scrub brush in the quadruped position/sitting | |||

** ''Carrying -'' small objects carried in the hand throughout the day, progressing to heavier items (UL); weight shifting, walking, standing with one foot on step, ball tossing towards the affected limb (LL) | |||

* '''Functional retraining''': Graded increase in functional use of the extremity as pain allows to increase independence in ADLs. Can be facilitated with [[Neurology Treatment Techniques|PNF]] pattern strengthening | |||

* '''Vocational rehabilitation and reintegration:''' Job site analysis, job specific conditioning/ work hardening, work capacity evaluation and transferable skills analysis.<ref name=":33" /><ref name=":26" /> | |||

* '''Contrast baths:''' Mild contrast baths may be useful in the early stages of CRPS to improve circulation. In more advanced CRPS, vasomotor changes interfere with these effects and cold water emersion can exacerbate symptoms. It is therefore usually not recommended in patients with CRPS.<ref name=":33" /> | |||

=== | === Psychotherapy === | ||

In CRPS, psychological factors are important to target to ensure optimal outcomes. Solely treating psychological aspects is however not sufficient, as clear biological elements exist in CRPS - evidence suggests that psychological interventions are most effective when combined with physiotherapy.<ref name=":33" /> | |||

There is currently no compelling evidence that psychiatric disorders contribute to the development of CRPS, but as a chronic pain condition, depression and distress can be common in these patients. <ref name=":33" />The aim of psychological interventions should be to address any factors that interfere with functional progression and to assist the psychological impact of a continued, severe pain experience<ref name=":33" />. | |||

[ | * '''Cognitive behavioural therapy [[Cognitive Behavioural Therapy|(CBT)]] and graded exposure:''' Particularly valuable, in combination with physiotherapy, to address [[kinesiophobia]]; bearing in mind that a certain level of activity avoidance is not unreasonable.<ref name=":33" /><ref name=":26" /><ref name=":4" />Catastrophic thinking has also been associated with increased pro-inflammatory cytokines which can exacerbate CRPS, and therefore needs to be addressed - education and correction of misconceptions relating to CRPS can be very valuable.<ref name=":33" /> | ||

* '''Stress management and [[Mindfulness Techniques For Pain Management|Mindfulness]]:''' Stress can be associated with increased catecholamine release which contributes to central sensitisation<ref name=":33" /> | |||

* '''ACT''' (Acceptance and commitment therapy)''':''' Can lead to improved functioning and quality of life, as well as self-efficacy.<ref name=":33" /> | |||

=== CRPS Management in Children === | |||

In a study of 28 children meeting the IASP criteria for CRPS, 92% reduced or eliminated their pain after receiving exercise therapy. <ref name=":4" />Physiotherapy (hydrotherapy, desensitisation and exercise) combined with CBT/counselling has proven efficacy in treating children with CRPS.<ref name=":4" /> | |||

== Case Reports == | == Case Reports == | ||

[https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21737520/ More Than Meets the Eye: Clinical Reflection and Evidence-Based Practice in an Unusual Case of Adolescent Chronic Ankle Sprain] | |||

[https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10907896/ Thoracic Spine Dysfunction in Upper Extremity Complex Regional Pain Syndrome Type I] | |||

== Resources == | == Resources == | ||

*[http://www.rsds.org Reflex Sympathetic Dystrophy Syndrome Association] | *[https://crps.europeanpainfederation.eu/#/ Eu Pain Federation -] free tool to guide PTs and OTs with designing treatment plans for CRPS | ||

*[https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9186375/ CRPS Diagnostic and Treatment Guidelines, 5th Edition] | |||

*[https://www.crpsconsortium.org/ International Research Consortium for CRPS (IRC)] | |||

*[https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/guidelines-policy/complex-regional-pain-syndrome-adults Complex regional pain syndrome in adults (2nd edition) UK guidelines for diagnosis, referral and management in primary and secondary care.] Royal College of Physicians, July 2018. | |||

*[http://www.rsds.org Reflex Sympathetic Dystrophy Syndrome Association] | |||

*[http://www.theacpa.org American Chronic Pain Association] | *[http://www.theacpa.org American Chronic Pain Association] | ||

*[http://www.mayoclinic.com Mayo Clinic] | *[http://www.mayoclinic.com Mayo Clinic] | ||

| Line 429: | Line 429: | ||

== Clinical Bottom Line == | == Clinical Bottom Line == | ||

CRPS is | CRPS is characterised by debilitating, persistent pain that is disproportionate in magnitude or duration to the typical course of pain after similar injury. It is a difficult condition to treat as the pathophysiology is often complex and diverse and is still not fully understood. High quality, robust evidence regarding effective treatment is still lacking, leading to no consensus regarding the optimal management of CRPS. | ||

== References == | == References == | ||

Latest revision as of 12:05, 25 September 2023

Original Editors - Katelyn Koeninger and Kristen Storrie from Bellarmine University's Pathophysiology of Complex Patient Problems project and Yves Hubar

Top Contributors Katelyn Koeninger, Kristen Storrie, Laura Ritchie, Laure-Anne Callewaert, Yves Hubar, Angeliki Chorti, Admin, Melissa Coetsee, Evan Thomas, Scott Cornish, Elaine Lonnemann, Kim Jackson, Rachael Lowe, Gayatri Jadav Upadhyay, Gwen Wyns, Matthias Steenwerckx, Vidya Acharya, Lucinda hampton, Habibu Salisu Badamasi, Jo Etherton, Claire Knott, Lauren Lopez, Maria Galve Villa, Michelle Lee, Richmond Stace, WikiSysop, Wendy Walker and Naomi O'Reilly

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS) is a term for a complex pain disorder characterised by continuing (spontaneous and/or evoked) regional pain that is seemingly disproportionate in time or degree to the usual course of any known trauma or lesion. [1] Specific clinical features include allodynia, hyperalgesia, sudomotor and vasomotor abnormalities, and trophic changes.

CRPS has a multifactorial pathophysiology involving pain dysregulation in the sympathetic and central nervous systems, and possible genetic, inflammatory, and psychological factors.

Many names have been used to describe this syndrome such as; Reflex Sympathetic Dystrophy, causalgia, algodystrophy, Sudeck’s atrophy, neurodystrophy and post-traumatic dystrophy. To standardise the nomenclature, the name complex regional pain syndrome was adopted in 1995 by the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP).[2]

Classification and Phenotypes[edit | edit source]

CRPS is commonly subdivided into Type I and Type II CRPS. Type I occurs in the absence of major nerve damage (minor nerve damage may be present), while Type II occurs following major nerve damage.[3] Despite this distinction, there is a large overlap in clinical features and the primary diagnostic criteria are identical, and the classification therefore may have little clinical importance.[1] [4][5][6][7]

Three stages (stage I - acute up to 3 months, stage II - dystrophic 3-6- months after onset, stage III - atrophic > 6 months) of CRPS progression have been proposed by Bonica in the past, but the existence of these stages has been suggested as unsubstantiated. [8][9] It is however possible for CRPS subtypes to evolve over time, currently referred to as "warm CRPS" (warm, red, dry and oedematous extremity, inflammatory phenotype) and "cold CRPS" (cold, blue or pale, sweaty and less oedematous, central phenotype). [10] Both of these subtypes present with comparable pain intensity. Warm CRPS is by far the most common in early CRPS, and cold CRPS tends to have a worse prognosis and more persistent symptomatology.[1]

Dimova and associates [11]recentrly proposed another classification based on the findings of the neurological examination. The first group of patients presents with a central phenotype, with motor signs, allodynia, and glove/stocking-like sensory deficits. The second cluster represents a pheripheral inflammation phenotype, involving edema, skin color changes, skin temperature changes, sweating, and trophic changes. The third group has a mixed presentation.

As noted from above, although classification for CRPS shows some variability, there is agreement on mechanisms of central and inflammatory origin. Further research is needed to reach clusters that lead to valid and effective treatment decisions.

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

Incidence and Prevalence[edit | edit source]

CRPS incidence appears to vary according to global location. For example, studies show that Minnesota has an incidence of 5.46 per 100,000 person-years for CRPS type I and 0.82 per 100,000 person-years for CRPS type II, whilst the Netherlands in 2006 had 26.2 cases per 100,000 person-years. Research shows that CRPS is more common in females than males, with a ratio of 3.5:1.[12] CRPS can affect people of all ages, including children as young as three years old and adults as old as 75 years, but typically is most prevalent in the mid-thirties. CRPS Type I occurs in 5% of all traumatic injuries, with 91% of all CRPS cases occurring after surgery.[13]

Location[edit | edit source]

The location of CRPS varies from person to person, mostly affecting the extremities, occurring slightly more in the lower extremities (+/- 60%) than in the upper extremities (+/- 40%). It can also appear unilaterally or bilaterally.[14]

Prognosis[edit | edit source]

Approximately 15% of early CRPS (up to 6-18 months duration) fail to recover and early onset of cold CRPS predicts poor recovery.[1]

Aetiology[edit | edit source]

Complex regional pain syndrome can develop after the occurrence of different types of injuries, such as:

- Minor soft tissue trauma (sprains)

- Surgeries

- Fractures, especially following immobilisation

- Contusions

- Crush injuries

- Nerve lesions

- Stroke

The onset is mostly associated with a trauma, immobilisation, injections, or surgery, but there is no relation between the grade of severity of the initial injury and the following syndrome. In 7% of cases there is no injury or surgery preceding the onset of CRPS.

A study found that excessive baseline pain (>5/10) in the week following wrist fracture surgery increases the risk of developing CRPS. [15] A stressful life and other psychological factors may be potential risk factors that impact the severity of symptoms in CRPS. [16]There is however no compelling evidence that psychiatric disorders contribute to the development of CRPS. [1]

Pathophysiology[edit | edit source]

Various mechanisms are at play in the development and maintenance of CRPS, including nerve injury, central and peripheral sensitisation, altered sympathetic function, inflammatory and immune factors, brain changes, genetic factors and psychological factors.[17] Little is however known about how these mechanisms interact and it is likely that the relative contribution of each mechanism varies between patients. [18]

CRPS usually follows trauma/surgery, and likely starts with normal peripheral nociceptive stimulation. Enhanced, altered and ongoing nociception can then lead to peripheral and central sensitisation (CS), with the latter regarded as a prominent mechanism underlying CRPS.[4][19]

Sustained neuroinflammation has lately received attention as a key factor in the initiation and perpetuation of CRPS. [18] Neuropeptides mediate the enhanced neurogenic inflammation and pain; they may activate microglia and astrocytes, resulting in a cascade of events that sensitise neurons and impact synaptic plasticity. [18] Upregulated cytokines, secreted by keratinocytes, exacerbate this phenomenon. [18] Immune cells may also modulate neuronal activity by releasing immunomodulatory factors. [18]

Psychological factors could maintain CRPS by their impact on catecholamine release and kinesiophobia. The central and peripheral nervous systems are connected through neural and chemical pathways, and can have direct control over the autonomic nervous system. It is for this reason that there can be changes in vasomotor and sudomotor responses without any impairment in the peripheral nervous system. For a more detailed review of the underlying mechanisms at play, see this article by Bruehl (2015).

Treatment approaches are aimed at normalising afferent inputs and reversing secondary changes associated with immobilisation.

Figure 1. Nociceptive (painful) information is relayed through the dorsal horn of the spinal cord for processing and modulation before cortical evaluation. [20]

Video below: more on the pathophysiology underlying CRPS.

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

CRPS is clinically characterised by sensory, autonomic, and motor disturbances. The table below shows an overview of these characteristics. [2] [4] [21] [6] [7] [22]

| Sensory disturbances | Allodynia and hyperalgesia

Hypoesthesia; Strange, disfigured or dislocated feeling in the limb[12] |

|---|---|

| Autonomic and inflammatory components | Swelling and oedema[12]

Hyperhidrosis; changes in sweating Abnormal skin blood flow Temperature changes[12] Colour changes (redness or pale) |

| Trophic changes | Thick, brittle, or rigid nails

Increased/decreased hair growth Thin, glossy, clammy skin[12] Osteopenia (chronic stage) |

| Motor dysfunction | Weakness of multiple muscles and atrophy [12]

Inability to initiate movement of the extremity Stiffness and reduced ROM Tremor or dystonia |

| Pain | Burning, deep, dull

Disproportionate Spontaneous and/or triggered by movement, noise, pressure on joint Pain may not be present in 7% of CRPS patients[12] |

Symptoms can spread beyond the area of the lesioned nerve in Type II. Ongoing neurogenic inflammation, vasomotor dysfunction, central sensitisation and maladaptive neuroplasticity contribute to the clinical phenotype of CRPS. [6] [14]

Associated Co-morbidities[edit | edit source]

CRPS may also be associated with:

- Impaired microcirculation [23]

- Asthma [12]

- Fractures [24]

- Cellulitis [25]

- Conversion Disorder [26]

- Depression/Anxiety

- Lymphedema [23]

- Malignancy [27]

- Migraines [12]

- Osteoporosis [12][24]

- Autoimmune dysfunction [28]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Differential diagnosis includes the direct effects of the following conditions: [13][29]

- Bony or soft tissue injury

- Peripheral neuropathy, nerve lesions

- Arthritis

- Infection

- Compartment syndrome

- Arterial insufficiency

- Raynaud’s Disease

- Lymphatic or venous obstruction (eg. DVT)

- Thoracic Outlet Syndrome (TOS)

- Gardner-Diamond Syndrome

- Erythromelalgia

- Self-harm or malingering

- Cellulitis

- Undiagnosed fracture

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

CRPS diagnosis is mainly based on patient history, clinical examination, and supportive investigations.

There are 4 diagnostic tools for CRPS in adult populations. These include the Veldman criteria, IASP criteria, Budapest Criteria, and Budapest Research Criteria.[30]

The Budapest Criteria[edit | edit source]

The Budapest criteria (also known as the IASP criteria and explicitly endorsed by the IASP) has been developed for the diagnosis of CRPS, but improvements still need to be made. [31][32][33] Clinical diagnostic criteria for CRPS are: [1]

- Continuing pain, which is disproportionate to any inciting event

- Must report at least one symptom in three of the four following categories:

- Sensory: hyperalgesia and/or allodynia

- Vasomotor: temperature asymmetry and/or skin colour changes and/or skin colour asymmetry

- Sudomotor/oedema: oedema and /or sweating changes and/or sweating asymmetry

- Motor/trophic: decreased range of motion and/or motor dysfunction (weakness, tremor, dystonia) and/or trophic changes (hair, nail, skin)

- Must display at least one sign at the time of evaluation in two or more of the following categories

- Sensory: hyperalgesia (to pinprick) and/or allodynia (to light touch/pressure/joint movement)

- Vasomotor: evidence of temperature asymmetry and/or skin colour changes and/or skin colour asymmetry

- Sudomotor/oedema: evidence of oedema and /or sweating changes and/or sweating asymmetry

- Motor/trophic: evidence of decreased range of motion and/or motor dysfunction (weakness, tremor, dystonia) and/or trophic changes (hair, nail, skin)

- There is no other diagnosis that better explains the signs and symptoms

The Budapest Criteria have excellent diagnostic sensitivity of 99% and a moderate specificity of 68%. [30] See the video below for more detail on the Budapest Criteria.

Other Tests[edit | edit source]

- Infrared Thermography: Infrared thermography (IRT) is an effective mechanism to find significant asymmetry in temperature between both limbs by determining if the affected side of the body shows vasomotor differences in comparison to the other side. It is reported having a sensitivity of 93% and a specificity of 89%. [35] This test is hard to obtain so it is not often used for diagnosing of CRPS. [32] [36][35]

- Sweat Testing: Determining if the patient sweats abnormally. Q-sweat is an adequate instrument to measure sweat production. The sweat samples should be taken from both sides of the body at the same time. [4][35]

- Radiographic testing: Irregularities in the bone structure and osteopenia of the affected side of the body can become visible with the use of X-rays. [4] [35]

- Three phase bone scan: A triple phase bone scan is the best method to rule out Type I CPRS. [37] With the use of technetium Tc 99m-labeled bisophosphonates, an increase in bone metabolism can be shown. Higher uptake of the substance means increased bone metabolism and the body part could be affected. [35] The triple-phase bone scan has the best sensitivity, NPV, and PPV compared to MRI and plain film radiographs.

- Bone densitometry: An affected limb often shows less bone mineral density and a change in the content of the bone mineral. During treatment of the CPRS the state of the bone mineral will improve. So this test can also be used to determine if the patient’s treatment is effective. [35]

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): MRI scans are useful to detect periarticular marrow oedema, soft tissue swelling and joint effusions. And in a later stage, atrophy and fibrosis of periarticular structures can be detected. But these symptoms are not exclusively signs of CRPS. [4][35]

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

The CRPS consortium has established a list of core outcome measures to be used for patients with CRPS (referred to as COMPACT).[38]

Patient reported Outcome Measures:

- PROMIS-29: Assesses 7 domains (physical function, pain interference, fatigue, depression, anxiety, sleep, social participation)

- NPRS: Numeric pain rating scale

- Short-form McGill Pain Questionnaire (SF-MPQ-2): Six neuropathic items capture pain quality

- Pain Catastrophising Scale

- EQ-5D-5L: Measurement of health state

- Pain Self-efficacy Questionnaire

- CRPS symptom questions: Derived from the Budapest Criteria

Clinical reported Outcome Measures:

- CRPS Severity Score (CSS): Includes 8 signs and 8 symptoms that reflect the sensory, vasomotor, sudomotor/edema and motor/trophic disorders of CPRS, coded based on the history and physical examination. Extent of changes in CSS scores over time are significantly associated with changes in pain intensity, fatigue, and functional impairments. Thus, the CSS appears to be valid and sensitive to change. A change of 5 or more CSS scale points reflects a clinically-significant change. [1]

Other Outcome Measures (not part of COMPACT):

- Various region specific functional measures can be used for either upper limb or lower limb CRPS, eg. Grip strength [39]

Examination[edit | edit source]

The diagnosis is based on the clinical presentation described above. Procedures start with taking a detailed medical history, taking into account any initiating trauma and any history of sensory, autonomic, and motor disturbances, as well as how the symptoms developed, the time frame, distribution and characteristics of pain. Assessment for any swelling, sweating, trophic and/or temperature increases, and motor abnormality in the disturbed area is important. Skin temperature differences may be helpful for diagnosis of CRPS. The original IASP criteria required only a history and subjective symptoms for a diagnosis of CRPS, but recent consensus guidelines have argued for the inclusion of objective findings. [40]

The clinical presentation of CRPS, and the underlying mechanisms, can differ between patients and even within a patient over time - it is therefore important assess underlying pain mechanisms in order to design targeted treatment for each individual.[1]

- Autonomic Dysfunction: The majority of patients with CRPS have bilateral differences in limb temperature and the skin temperature depends of the chronicity of the disease. In the acute stages, temperature increases are often concomitant with a white or reddish colouration of the skin and swelling. where the syndrome is chronic, the temperature will decrease and is associated with a bluish tint to the skin and atrophy. [41]

- Motor Dysfunction: Studies have shown that approximately 70% of the patients with CRPS show muscle weakness in the affected limb, exaggerated tendon reflexes or tremor, irregular myoclonic jerks, and dystonic muscle contractions. Muscle dysfunction often coincides with a loss of range of motion in the distal joints. [42]

- Sensory Dysfunction: The distal ends of the extremities require attention when examining a patient with CRPS. However, common findings of regional neuropathic and motor dysfunction have shown us that it is important to broaden the examination both proximally and contralaterally. [41]Light touch, pinprick, temperature and vibration sensation should be assessed for a complete picture of the CRPS. [41] Most assessments are interlinked, for example, when vibration sensation is highly positive, light touch should also be positive. [41]To help distinguish the findings of a sensory dysfunction, bilateral comparisons are made. [42][41]Also see Quantitative Sensory Testing.

Multidisciplinary Management[edit | edit source]

CRPS can be very difficult to treat successfully, as it involves both central and peripheral pathophysiology, as well as frequent psychosocial components.[1] This complexity of CRPS calls for an interdisciplinary approach, where the entire management team collaborates and focuses on all the relevant biopsychosocial elements. In many settings this is not feasible - in such cases a multidisciplinary approach is still very important to address the multifactorial nature of CRPS.[1] Treatment of complex regional pain syndrome should be immediate, and most importantly directed toward functional restoration. Functional restoration emphasises physical activity, desensitisation and normalisation of sympathetic tone, and involves steady progression. [1]

Treatment Overview[edit | edit source]

Despite multiple interventions being described and commonly used, the optimal management of CRPS is still under debate. The latest published evidence from Cochrane and non‐Cochrane systematic reviews of the efficacy, effectiveness, and safety interventions did not identify high‐certainty evidence for the effectiveness of any therapy for CRPS. [43] This paper was the first update of the original Cochrane review in 2013. [43]

Nevertheless, the following table summarises treatment recommendations for CRPS. These strategies are based on the Malibu CRPS algorithm and most recent treatment guidelines.[1]

| Description & Modalities | Team members | |

|---|---|---|

| Functional Restoration | ||

| Phase 1: Activation of pre-sensorimotor cortices | Graded motor imagery

Visual tactile discrimination |

PT/OT |

| Phase 2: Gentle active ROM | Progressive AROM

Isometric strengthening |

PT |

| Phase 3: Weight bearing | UL: carrying items

LL: partial weight bearing |

PT/OT |

| Desensitisation | Progressive stimulation with textures (soft to more rough)

Contrast baths with progressive broadening of the temp difference |

OT/PT |

| Pain Management | Sympathetic blocks and/or medication to allow engagement with functional restoration

Functional restoration addresses pain by normalising afferent inputs and central processing |

MD

PT |

| Edema Management | Pressure garments

Aquatic therapy General aerobic activity |

PT/OT |

| Psychological approaches | CBT and exposure-based therapy if patient presents with kinesiophobia

Psychotherapy if depression/anxiety is present |

Psych/PT |

| Secondary impairments | Local muscle spasm, reactive bracing and disuse atrophy secondary to pain needs to be addressed | PT |

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

Medical management is aimed at achieving sufficient pain relief, in order to allow for rehabilitation interventions to commence and progress. Most medications used for CRPS lack high quality evidence, and most treatment regimes are extrapolated from evidence for related neuropathic conditions. CRPS does however differ from other neuropathic conditions in that additional circulatory, bone and inflammatory pathways are present[1]. Patients also present with a varying dominant mechanisms (including central sensitisation, motor abnormalities and sympathetic abnormalities), and it is therefore important to base medication prescription on reasoning regarding evident underlying mechanisms. Below is a summary of the possible medical interventions for patients with CRPS:

| Description | Evidence/ considerations | |

|---|---|---|

| Pharmacotherapy | ||

| Anti-inflammatory drugs | NSAIDs (esp Ketoprofen), COX-2 inhibitors, corticosteroids | Useful to address the inflammatory component of CRPS, but often not effective as neurogenic inflammation mostly dominant. Risks regarding long-term use needs to be considered |

| Biphosponates | Have immune-modulatory properties and modulate bone metabolism | May help in acute stages or in selected subtypes of CRPS (where osteopenia is evident), but the evidence is lacking |

| Cation-Channel blockers | Anticonvulsants (gabapentin/pregabalin) | Proven efficacy for other neuropathic pain conditions; evidence for CRPS is lacking |

| Tricyclic drugs | Anti-depressants that augment descending inhibition | Effective for other neuropathic conditions; worth considering in patients with associated insomnia, depression and/or anxiety |

| Opioids | Tramadol

Methadone |

Tolerance and long-term toxicity are important concerns, and can worsen allodynia and hyperalgesia; daily use is not recommended in CRPS - only for excruciating pain |

| NMDA Antagonists | Ketamine | High risk of toxicity; IV ketamine may have positive effects on central sensitisation |

| Alpha2-adrenergic Agonists/ Ca-channel blockers | Clonidine

Nifedipine |

Evidence is contradictory. Adverse effects can occur |

| Calcitonin | Hormone produced by the thyroid | A meta-analysis demonstrated benefits of intranasal administration, but subsequent studies had conflicting results |

| Immune modulators | Steroids

Immunoglobulins (IVIG) |

Evidence suggests that early initiation (after trauma), followed by tapering, may be effective

Steroid injections are ineffective IVIG has limited evidence |

| Other | ||

| Topical treatment | Lidocaine

Capsaicin |

Capsaicin can be intolerably painful in the presence of hyperalgesia |

| Supplements | Vitamin C | Daily Vit C following limb fracture or surgery may prevent CRPS |

| Sympathetic blocks | Local anaesthetic block applied at the transverse process of C6 or L2/3 | High quality evidence is lacking, but may be useful for a subset of patients with prominent vasomotor dysfunction, to provide pain relief and a window of opportunity for rehabilitation techniques[1][35] |

| Spinal cord stimulations | Aims to inhibit the nociceptive pathways at the level of the dorsal column | Reserved for use when patients are not responding to other interventions. Safe and proven long-term effective for chronic CRPS[1] |

| Dorsal root ganglion stimulation[3] | Aims to modulate nociceptive pathways at the dorsal root | Evidence shows reduced pain, improved quality of life and function if conservative therapy has failed[1] |

It is likely that medication prescription will need to be adapted over time as CRPS progresses or patients develop tolerance. The following table presents a consensus-based pharmacotherapy guide based on clinical findings in CRPS: [1]

| Reason for inability to start/progress with rehab | Pharmacotherapy reccommendations |

|---|---|

| Mild to moderate pain | Simple analgesics and/or blocks |

| Excruciating pain | Opioids and/or blocks |

| Inflammation and oedema | Steroids, NSAIDs, immune modulators |

| Depression, insomnia | Anti-depressants |

| Severe allodynia/hyperalgesia | Anticonvulsants and/or NMDA antagonists |

| Osteopenia and trophic changes | Calcitonin or biphosphonates |

| Profound vasomotor disturbance | Calcium channel blockers and/or blocks |

Physiotherapy Management[edit | edit source]

Various consensus groups have emphasised that physiotherapy is of utmost importance in restoring function in patients with CRPS.[4][1] Studies have shown that exercise-based physiotherapy is effective in managing pain and reducing impairment. [1][44]

Physiotherapy aims to restore function, using the following intervention strategies: