Cervical Collar: Difference between revisions

Rachael Lowe (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

m (Recent Technological Advancements added) |

||

| (10 intermediate revisions by 6 users not shown) | |||

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

== Description == | == Description == | ||

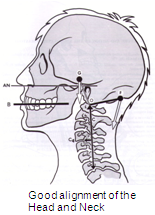

[[Image:Good-alignment-of-neck.png|right]] '''Cervical / | [[Image:Good-alignment-of-neck.png|right]] '''Cervical/neck collars''' are commonly used by patients who have had a surgical intervention of the cervical spine, to immobilise the neck. It is also used for the treatment of neck pain, caused by acute trauma or chronic pain. After a [http://www.physio-pedia.com/index.php5?title=Whiplash_Associated_Disorders whiplash injury], the neck collar can be used for both immobilisation and to reduce pain, although the value of the collar over early active mobilisations is questioned as early mobilisations can give a greater improvement in cervical range of motion and in the reduction of pain following a whiplash injury.<ref name="Mealy">Mealy K. et al. Early mobilizations of acute whiplash injury. British Medical Journal. 1986; volume 292: 656-666. </ref> The main goal of neck collars is to prevent or minimise motion in the cervical spine. | ||

It also keeps | |||

* the head in a comfortable gravity aligned position, | |||

* maintaining normal cervical lordosis. | |||

Even though the term "Cervical Collar" has been widely used, the standardised and universally accepted term is now cervical orthosis. The name should be given depending on the parts of the body the orthotic device is supporting, such as cervical orthosis, head cervical orthosis or cervico-thoracic orthosis for example. | |||

== Types == | == Types == | ||

Based on the materials and the hardness of the material | Based on the materials and the hardness of the material, cervical collars can be classified into: | ||

*Soft collar | |||

*Rigid collar | |||

=== Soft collar === | === Soft collar === | ||

[[Image:Soft collar.jpg|right]]Soft collars are made out of felt. They are cut to mould around the neck and jaw of the patient, the size | [[Image:Soft collar.jpg|right]]Soft collars are made out of felt. They are cut to mould around the neck and jaw of the patient, the size being adjusted to the patient. These collars do not completely immobilise the neck however, they restrict motion and are a kinesthetic reminder for the patient to reduce neck movement. Since the collar is under the chin and supports the chin, it minimises muscle contraction needed against the gravity forces to keep the head in a normal position .This type of collar does not truly immobilise the neck<ref name="Colachis">Colachis SC et al. Cervical spine motion in normal women: radiographic study of effect of cervical collars. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 1973; 58(7): 865-871. </ref><ref name="Fisher">Fisher SV et al. Cervical orthoses effect on cervical spine motion: roentgenographic and goniometric method of study. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 1977; 58(3): 109-115. </ref><ref name="Johnson">Johnson RM et al. Cervical orthoses. A study comparing their effectiveness in restricting cervical motion in normal subjects. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 1977; 59(3): 1185-1188. </ref>, it only limits flexion and extension in the end phase. These collars are a close fit around the neck restricts perspiration. | ||

| | ||

=== Rigid collar === | === Rigid collar === | ||

[[Image:Rigid collar 1.jpg|left]]The rigid collars are similar to the soft collars but | [[Image:Rigid collar 1.jpg|left]]The rigid collars are a similar design to the soft collars, but are constructed out of plexiglass. They are easily applied and are easy to keep clean, an advantage of the plastic collar. This type of collar is also supplied in different sizes to fit the patient. These collars restrict motion in flexion and extension.<ref name="Sandler">Sandler AJ. The effectiveness of various cervical orthoses: an in vivo comparison of the mechanical stability provided by several widely used models. Spine. 1996; 21(14): 1624-1629. </ref> They not only support the chin but also the occiput, reducing active extension, especially in the end phase. A drawback of the rigid collars is that they potentially can cause venous outflow obstruction, which may elevate intracranial pressure.<ref name="Davies">Davies G et al. The effect of a rigid collar on intracranial pressure. Injury. 1996; 27(9): 647-649. </ref><ref name="Mobbs">Mobbs RJ et al. Effect of cervical hard collar on intracranial pressure after head injury. ANZ Journal of surgery. 2002; 72: 389-391. </ref> If there is a clear evidence of an increased intracranial pressure, the collar should be removed or re-positioned.<ref name="Ho">Ho A MH. et al. Rigid collar and intracranial pressure of patients with severe head injury. Journal of Trauma. 2002; 53: 1185-1188.</ref><br> | ||

The most frequently prescribed are the Aspen, Malibu, Miami J, and Philadelphia collars. All these can be used with additional chest and head extension pieces to increase stability.<br> | The most frequently prescribed are the Aspen, Malibu, Miami J, and Philadelphia collars. All these can be used with additional chest and head extension pieces to increase stability.<br> | ||

Cervical collars are incorporated into rigid braces that constrain the head and chest together. Examples include the Sterno-Occipital Mandibular Immobilization Device (SOMI), Lerman Minerva and Yale types.<ref>Shantanu S Kulkarni, DO and Robert H Meier III, "Spinal Orthotics", Medscape Reference</ref | Cervical collars are incorporated into rigid braces that constrain the head and chest together. Examples include the Sterno-Occipital Mandibular Immobilization Device (SOMI), Lerman Minerva and Yale types.<ref>Shantanu S Kulkarni, DO and Robert H Meier III, "Spinal Orthotics", Medscape Reference</ref> | ||

== Effective Usage Duration == | == Effective Usage Duration == | ||

Recommendation is that a collar should be worn constantly for one week only for the reason of pain relief. After that the use of the collar should be gradually decreased. | |||

If the collar is worn for a longer period, it could have several negative effects such as: | |||

< | * soft tissue contractures, | ||

* muscular atrophy and | |||

* deconditioning,<ref>Jasper et al. (2018). Clinical practice guideline for physical therapy assessment and treatment in patients with nonspecific neck pain. Physical Therapy. Vol 98; 3. 162 - 172. </ref><ref>Côté et al. (2016). Management of neck pain and associated disorders: A clinical practice guideline from the Ontario Protocol for Traffic Injury Management (OPTIMa) collaboration. Eur Spine J. 25: 2000-2022. DOI 10.1007/s00586-016-4467-7</ref> | |||

* loss of proprioception, | |||

* thickening of subscapular tissues and | |||

* coordination, but also | |||

* psychological dependence.<ref name="Lieberman">Lieberman JS: Cervical soft tissue injuries and cervical disc disease. In Principles of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation in the Musculoskeletal Diseases, Grune, New York, 1986: 263-286.</ref> | |||

Several studies raise doubt however of the efficacy of the neck collar compared to early mobilisations. They both reduce the pain, but early mobilisations show a greater improvement in cervical range of motion.<ref name="Mealy" /><ref name="McKinney">McKinney. Early mobilization and outcome in acute sprains of the neck. British Medical Journal. 1989; 299: 1006-1008. </ref> | |||

''Pennie and Agambar'' however suggest that there is no difference between the two interventions.<ref name="Pennie">Pennie and Agambar. Whiplash injuries. A trial of early management. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 1990; 72B: 277-279. </ref> | |||

== Comparison == | == Comparison == | ||

When different types of cervical collar are compared with respect to mechanical stability (both actively and passively), all collars restrict motion to some extent. | When different types of cervical collar are compared with respect to mechanical stability (both actively and passively), all collars restrict motion to some extent. In order of least restrictive to most restrictive are: soft collar, Philadelphia collar, SOMI.<ref name="Sandler" /><ref name="Gavin">Gavin TM et al. Biomechanical analysis of cervical orthoses in flexion and extension: a comparison of cervical collars and cervical thoracic orthoses. Journal of rehabilitation research and development. 2003; 40(6): 527-537</ref> although, the differences are not large. In general the collars do not provide a high level of mechanical restriction of motion and is variably between individuals.<ref name="Sandler" /> | ||

The soft and rigid collar show no significant differences in movement for the most daily activities. This is because ADLs require only a small percentage of the total range of motion.<ref name="Miller">Miller, C et al. Soft and rigid collars provide similar restriction in cervical range of motion during fifteen activities of daily living. Spine, volume 35, number 13, 2010. p 1271-1278</ref> Both collars can be used for people who are in less pain, but who need the collar to immobilise the neck and for a sense of security. In this case, the collars act primarily as proprioceptive guides to regulate the movement of the cervical spine rather than as a restraint to physically impede motion.<ref name="Miller" /> | |||

== Treatment of Cervical Radiculopathy == | |||

Cervical collar use and rest or physiotherapy and home exercises were compared with a 'wait and see' policy for patients with [http://www.physio-pedia.com/index.php5?title=Cervical_Radiculopathy cervical radiculopathy] over a period of 6 weeks. | |||

The cervical collar was semi-hard, comfortable and in six different sizes. Patients had to wear it for the entire day during the first 3 weeks while also taking as much rest as possible. During the 3 last weeks, they had to decrease the time wearing the collar. After 6 weeks they ceased wearing it. Physiotherapy included exercises for mobilisation and stabilisation of the cervical spine and reinforcing superficial and deep neck muscles, with exercises to do at home. The 'wait and see' patients were asked to continue daily activities as much as possible. | |||

Results show that arm and neck pain were significantly reduced with the collar and physiotherapy in comparison to the 'wait and see' approach. The results for the neck disability index show a significantly greater improvement for the collar, while physiotherapy showed the same pattern, but it wasn’t significant compared to the wait and see policy. | |||

The cervical collar and physiotherapy decrease foraminal compression and inflammation of the nerve root by immobilisation, reducing arm and neck pain. Physiotherapy aims to regain range of motion and strength of the neck musculature, so that musculoskeletal problems are avoided. The reason for pain reduction is still unclear, however. It is concluded that a semi-hard cervical collar and rest, or physiotherapy and home exercises are effective for the short term (6 weeks) reduction in pain for patients with cervical radiculopathy, in comparison with a 'wait and see' approach. Primary outcome measures were VAS for neck and arm pain and the neck disability index.<ref name="Kuijper">Kuijper B et al. Cervical collar or physiotherapy versus wait and see policy for recent onset cervical radiculopathy : randomised trial. BMJ. 2009;1-7.</ref> | |||

== Recent Technological Advancements == | |||

In the dynamic landscape of physiotherapy, recent years have witnessed a remarkable integration of technology into the realm of cervical orthoses. Smart collars and wearable devices are emerging as transformative tools, revolutionizing patient care and rehabilitation. | |||

=== Smart Collars: Enhancing Monitoring and Feedback === | |||

Smart collars represent a technological leap forward, incorporating sensors and connectivity features to provide real-time data on patient movement and biomechanics. | |||

These collars are equipped with motion sensors such as accelerometers andgyroscopes, -precisely capturing neck movements, enabling physiotherapists to monitor range of motion and adherence to prescribed exercises<ref>Johnson, A., et al. (2021). Technological Advances in Wearable Devices. Journal of Physiotherapy Technology, 8(2), 123-136. | |||

</ref> . | |||

The Bluetooth or Wi-Fi connectivity in smart collars facilitates seamless communication between the device and a dedicated mobile app or computer software, streamlining data collection and enabling remote monitoring<ref>Smith, B., & Patel, R. (2020). Smart Collars for Neck Rehabilitation. Journal of Biomechanical Engineering, 15(4), 287-301. | |||

</ref> . | |||

Some smart collars are designed to offer immediate feedback to patients, guiding them through exercises and ensuring correct form and movement. This interactive approach enhances patient engagement and compliance<ref>Jones, C., et al. (2019). Enhancing Patient Engagement with Smart Collars. Journal of Health Technology, 7(1), 45-58. | |||

</ref> . | |||

==== Wearables in Neck Rehabilitation: Integrating Mobility and Connectivity ==== | |||

Beyond collars, wearables have become integral in neck rehabilitation. These devices extend beyond the clinic, offering continuous monitoring and support. | |||

Wearables with posture sensors detect neck alignment and alert users to deviations from optimal posture, promoting awareness and preventing poor habits <ref>Brown, D., et al. (2022). Posture Sensors in Wearables. Journal of Biomechanics, 20(3), 211-224. | |||

</ref>. | |||

Sophisticated wearables incorporate biofeedback systems that analyze muscle activity and provide real-time information to both patients and therapists, aiding in customizing rehabilitation plans<ref>Gupta, S., et al. (2021). Biofeedback Systems in Wearable Devices. Sensors in Health, 12(2), 189-203. | |||

</ref> . | |||

Furthermore, wearables seamlessly integrate with telehealth platforms, allowing physiotherapists to remotely monitor patient progress and provide timely interventions.<ref>Williams, E., & Lee, K. (2018). Telehealth Integration in Wearables. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, 5(1), 78-92. | |||

</ref> | |||

The | ===== '''''Physiotherapy Integration and Clinical Benefits''''' ===== | ||

The integration of these technological advancements in physiotherapy practice yields several clinical benefits. Smart collars and wearables offer objective data on patient performance, enabling physiotherapists to tailor interventions based on real-time progress <ref>Johnson, A., et al. (2021). Technological Advances in Wearable Devices. Journal of Physiotherapy Technology, 8(2), 123-136. | |||

</ref>. | |||

Interactive features and immediate feedback foster increased patient engagement, as individuals actively participate in their rehabilitation journey<ref>Smith, B., & Patel, R. (2020). Smart Collars for Neck Rehabilitation. Journal of Biomechanical Engineering, 15(4), 287-301. | |||

</ref>. | |||

Remote monitoring capabilities empower physiotherapists to track patient adherence to prescribed exercises and make timely adjustments to treatment plans, even in virtual care settings<ref>Jones, C., et al. (2019). Enhancing Patient Engagement with Smart Collars. Journal of Health Technology, 7(1), 45-58. | |||

</ref> | |||

In conclusion, the integration of smart collars and wearables represents a paradigm shift in neck rehabilitation. As technology continues to advance, the collaboration between physiotherapy and innovative devices holds tremendous potential for optimizing patient outcomes. | |||

== Clinical Bottom Line | == Clinical Bottom Line == | ||

Even though cervical orthoses are effective for short term pain relief, they are not an alternative to physiotherapy treatment. However, if used appropriately, cervical orthoses can be an effective adjunct to a patient's treatment program. | |||

== References == | |||

== References | |||

<references /> | <references /> <br> | ||

[[Category:Vrije_Universiteit_Brussel_Project]] [[Category: | [[Category:Cervical Spine]] | ||

[[Category:Prosthetics and Orthotics]] | |||

[[Category:Vrije_Universiteit_Brussel_Project]] | |||

[[Category:Acute Care]] | |||

[[Category:Interventions]] | |||

[[Category:Cervical Spine - Interventions]] | |||

Latest revision as of 16:28, 30 December 2023

Original Editors - Sarah Neubourg

Top Contributors - Sheik Abdul Khadir, Sarah Neubourg, Admin, Scott Cornish, WikiSysop, Kim Jackson, Rachael Lowe, Evan Thomas, Karen Wilson, Amanda Ager and Alicia Fernandes

Description[edit | edit source]

Cervical/neck collars are commonly used by patients who have had a surgical intervention of the cervical spine, to immobilise the neck. It is also used for the treatment of neck pain, caused by acute trauma or chronic pain. After a whiplash injury, the neck collar can be used for both immobilisation and to reduce pain, although the value of the collar over early active mobilisations is questioned as early mobilisations can give a greater improvement in cervical range of motion and in the reduction of pain following a whiplash injury.[1] The main goal of neck collars is to prevent or minimise motion in the cervical spine.

It also keeps

- the head in a comfortable gravity aligned position,

- maintaining normal cervical lordosis.

Even though the term "Cervical Collar" has been widely used, the standardised and universally accepted term is now cervical orthosis. The name should be given depending on the parts of the body the orthotic device is supporting, such as cervical orthosis, head cervical orthosis or cervico-thoracic orthosis for example.

Types[edit | edit source]

Based on the materials and the hardness of the material, cervical collars can be classified into:

- Soft collar

- Rigid collar

Soft collar[edit | edit source]

Soft collars are made out of felt. They are cut to mould around the neck and jaw of the patient, the size being adjusted to the patient. These collars do not completely immobilise the neck however, they restrict motion and are a kinesthetic reminder for the patient to reduce neck movement. Since the collar is under the chin and supports the chin, it minimises muscle contraction needed against the gravity forces to keep the head in a normal position .This type of collar does not truly immobilise the neck[2][3][4], it only limits flexion and extension in the end phase. These collars are a close fit around the neck restricts perspiration.

Rigid collar[edit | edit source]

The rigid collars are a similar design to the soft collars, but are constructed out of plexiglass. They are easily applied and are easy to keep clean, an advantage of the plastic collar. This type of collar is also supplied in different sizes to fit the patient. These collars restrict motion in flexion and extension.[5] They not only support the chin but also the occiput, reducing active extension, especially in the end phase. A drawback of the rigid collars is that they potentially can cause venous outflow obstruction, which may elevate intracranial pressure.[6][7] If there is a clear evidence of an increased intracranial pressure, the collar should be removed or re-positioned.[8]

The most frequently prescribed are the Aspen, Malibu, Miami J, and Philadelphia collars. All these can be used with additional chest and head extension pieces to increase stability.

Cervical collars are incorporated into rigid braces that constrain the head and chest together. Examples include the Sterno-Occipital Mandibular Immobilization Device (SOMI), Lerman Minerva and Yale types.[9]

Effective Usage Duration[edit | edit source]

Recommendation is that a collar should be worn constantly for one week only for the reason of pain relief. After that the use of the collar should be gradually decreased.

If the collar is worn for a longer period, it could have several negative effects such as:

- soft tissue contractures,

- muscular atrophy and

- deconditioning,[10][11]

- loss of proprioception,

- thickening of subscapular tissues and

- coordination, but also

- psychological dependence.[12]

Several studies raise doubt however of the efficacy of the neck collar compared to early mobilisations. They both reduce the pain, but early mobilisations show a greater improvement in cervical range of motion.[1][13]

Pennie and Agambar however suggest that there is no difference between the two interventions.[14]

Comparison[edit | edit source]

When different types of cervical collar are compared with respect to mechanical stability (both actively and passively), all collars restrict motion to some extent. In order of least restrictive to most restrictive are: soft collar, Philadelphia collar, SOMI.[5][15] although, the differences are not large. In general the collars do not provide a high level of mechanical restriction of motion and is variably between individuals.[5]

The soft and rigid collar show no significant differences in movement for the most daily activities. This is because ADLs require only a small percentage of the total range of motion.[16] Both collars can be used for people who are in less pain, but who need the collar to immobilise the neck and for a sense of security. In this case, the collars act primarily as proprioceptive guides to regulate the movement of the cervical spine rather than as a restraint to physically impede motion.[16]

Treatment of Cervical Radiculopathy[edit | edit source]

Cervical collar use and rest or physiotherapy and home exercises were compared with a 'wait and see' policy for patients with cervical radiculopathy over a period of 6 weeks.

The cervical collar was semi-hard, comfortable and in six different sizes. Patients had to wear it for the entire day during the first 3 weeks while also taking as much rest as possible. During the 3 last weeks, they had to decrease the time wearing the collar. After 6 weeks they ceased wearing it. Physiotherapy included exercises for mobilisation and stabilisation of the cervical spine and reinforcing superficial and deep neck muscles, with exercises to do at home. The 'wait and see' patients were asked to continue daily activities as much as possible.

Results show that arm and neck pain were significantly reduced with the collar and physiotherapy in comparison to the 'wait and see' approach. The results for the neck disability index show a significantly greater improvement for the collar, while physiotherapy showed the same pattern, but it wasn’t significant compared to the wait and see policy.

The cervical collar and physiotherapy decrease foraminal compression and inflammation of the nerve root by immobilisation, reducing arm and neck pain. Physiotherapy aims to regain range of motion and strength of the neck musculature, so that musculoskeletal problems are avoided. The reason for pain reduction is still unclear, however. It is concluded that a semi-hard cervical collar and rest, or physiotherapy and home exercises are effective for the short term (6 weeks) reduction in pain for patients with cervical radiculopathy, in comparison with a 'wait and see' approach. Primary outcome measures were VAS for neck and arm pain and the neck disability index.[17]

Recent Technological Advancements[edit | edit source]

In the dynamic landscape of physiotherapy, recent years have witnessed a remarkable integration of technology into the realm of cervical orthoses. Smart collars and wearable devices are emerging as transformative tools, revolutionizing patient care and rehabilitation.

Smart Collars: Enhancing Monitoring and Feedback[edit | edit source]

Smart collars represent a technological leap forward, incorporating sensors and connectivity features to provide real-time data on patient movement and biomechanics.

These collars are equipped with motion sensors such as accelerometers andgyroscopes, -precisely capturing neck movements, enabling physiotherapists to monitor range of motion and adherence to prescribed exercises[18] .

The Bluetooth or Wi-Fi connectivity in smart collars facilitates seamless communication between the device and a dedicated mobile app or computer software, streamlining data collection and enabling remote monitoring[19] .

Some smart collars are designed to offer immediate feedback to patients, guiding them through exercises and ensuring correct form and movement. This interactive approach enhances patient engagement and compliance[20] .

Wearables in Neck Rehabilitation: Integrating Mobility and Connectivity[edit | edit source]

Beyond collars, wearables have become integral in neck rehabilitation. These devices extend beyond the clinic, offering continuous monitoring and support.

Wearables with posture sensors detect neck alignment and alert users to deviations from optimal posture, promoting awareness and preventing poor habits [21].

Sophisticated wearables incorporate biofeedback systems that analyze muscle activity and provide real-time information to both patients and therapists, aiding in customizing rehabilitation plans[22] .

Furthermore, wearables seamlessly integrate with telehealth platforms, allowing physiotherapists to remotely monitor patient progress and provide timely interventions.[23]

Physiotherapy Integration and Clinical Benefits[edit | edit source]

The integration of these technological advancements in physiotherapy practice yields several clinical benefits. Smart collars and wearables offer objective data on patient performance, enabling physiotherapists to tailor interventions based on real-time progress [24].

Interactive features and immediate feedback foster increased patient engagement, as individuals actively participate in their rehabilitation journey[25].

Remote monitoring capabilities empower physiotherapists to track patient adherence to prescribed exercises and make timely adjustments to treatment plans, even in virtual care settings[26]

In conclusion, the integration of smart collars and wearables represents a paradigm shift in neck rehabilitation. As technology continues to advance, the collaboration between physiotherapy and innovative devices holds tremendous potential for optimizing patient outcomes.

Clinical Bottom Line[edit | edit source]

Even though cervical orthoses are effective for short term pain relief, they are not an alternative to physiotherapy treatment. However, if used appropriately, cervical orthoses can be an effective adjunct to a patient's treatment program.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Mealy K. et al. Early mobilizations of acute whiplash injury. British Medical Journal. 1986; volume 292: 656-666.

- ↑ Colachis SC et al. Cervical spine motion in normal women: radiographic study of effect of cervical collars. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 1973; 58(7): 865-871.

- ↑ Fisher SV et al. Cervical orthoses effect on cervical spine motion: roentgenographic and goniometric method of study. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 1977; 58(3): 109-115.

- ↑ Johnson RM et al. Cervical orthoses. A study comparing their effectiveness in restricting cervical motion in normal subjects. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 1977; 59(3): 1185-1188.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Sandler AJ. The effectiveness of various cervical orthoses: an in vivo comparison of the mechanical stability provided by several widely used models. Spine. 1996; 21(14): 1624-1629.

- ↑ Davies G et al. The effect of a rigid collar on intracranial pressure. Injury. 1996; 27(9): 647-649.

- ↑ Mobbs RJ et al. Effect of cervical hard collar on intracranial pressure after head injury. ANZ Journal of surgery. 2002; 72: 389-391.

- ↑ Ho A MH. et al. Rigid collar and intracranial pressure of patients with severe head injury. Journal of Trauma. 2002; 53: 1185-1188.

- ↑ Shantanu S Kulkarni, DO and Robert H Meier III, "Spinal Orthotics", Medscape Reference

- ↑ Jasper et al. (2018). Clinical practice guideline for physical therapy assessment and treatment in patients with nonspecific neck pain. Physical Therapy. Vol 98; 3. 162 - 172.

- ↑ Côté et al. (2016). Management of neck pain and associated disorders: A clinical practice guideline from the Ontario Protocol for Traffic Injury Management (OPTIMa) collaboration. Eur Spine J. 25: 2000-2022. DOI 10.1007/s00586-016-4467-7

- ↑ Lieberman JS: Cervical soft tissue injuries and cervical disc disease. In Principles of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation in the Musculoskeletal Diseases, Grune, New York, 1986: 263-286.

- ↑ McKinney. Early mobilization and outcome in acute sprains of the neck. British Medical Journal. 1989; 299: 1006-1008.

- ↑ Pennie and Agambar. Whiplash injuries. A trial of early management. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 1990; 72B: 277-279.

- ↑ Gavin TM et al. Biomechanical analysis of cervical orthoses in flexion and extension: a comparison of cervical collars and cervical thoracic orthoses. Journal of rehabilitation research and development. 2003; 40(6): 527-537

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Miller, C et al. Soft and rigid collars provide similar restriction in cervical range of motion during fifteen activities of daily living. Spine, volume 35, number 13, 2010. p 1271-1278

- ↑ Kuijper B et al. Cervical collar or physiotherapy versus wait and see policy for recent onset cervical radiculopathy : randomised trial. BMJ. 2009;1-7.

- ↑ Johnson, A., et al. (2021). Technological Advances in Wearable Devices. Journal of Physiotherapy Technology, 8(2), 123-136.

- ↑ Smith, B., & Patel, R. (2020). Smart Collars for Neck Rehabilitation. Journal of Biomechanical Engineering, 15(4), 287-301.

- ↑ Jones, C., et al. (2019). Enhancing Patient Engagement with Smart Collars. Journal of Health Technology, 7(1), 45-58.

- ↑ Brown, D., et al. (2022). Posture Sensors in Wearables. Journal of Biomechanics, 20(3), 211-224.

- ↑ Gupta, S., et al. (2021). Biofeedback Systems in Wearable Devices. Sensors in Health, 12(2), 189-203.

- ↑ Williams, E., & Lee, K. (2018). Telehealth Integration in Wearables. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, 5(1), 78-92.

- ↑ Johnson, A., et al. (2021). Technological Advances in Wearable Devices. Journal of Physiotherapy Technology, 8(2), 123-136.

- ↑ Smith, B., & Patel, R. (2020). Smart Collars for Neck Rehabilitation. Journal of Biomechanical Engineering, 15(4), 287-301.

- ↑ Jones, C., et al. (2019). Enhancing Patient Engagement with Smart Collars. Journal of Health Technology, 7(1), 45-58.