Cauda Equina Syndrome: Difference between revisions

Scott Buxton (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

(I added the heading (Risk factors)) |

||

| (145 intermediate revisions by 21 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

<div class="editorbox"> | <div class="editorbox"> | ||

'''Special Contribution''' - [https://www.linkedin.com/in/laura-finucane-76394b90/?ppe=1 Laura Finucane], [https://www.linkedin.com/in/sue-greenhalgh-18407751/?ppe=1 Sue Greenhalgh], [https://www.linkedin.com/in/chris-mercer-4628b58b/?ppe=1 Chris Mercer], | |||

'''Original Editor '''- [[User:Laurie Fiegle|Laurie Fiegle]] and [[User:Tabitha Korona|Tabitha Korona]] | '''Original Editor '''- [[User:Laurie Fiegle|Laurie Fiegle]] and [[User:Tabitha Korona|Tabitha Korona]] | ||

'''Top Contributors''' - {{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}} | |||

</div> | |||

== | == Definition == | ||

[[Image:Cauda Equina.gif|right|200px|Cauda Equina]][[Cauda Equina|Cauda equina]] syndrome (CES) is a rare but serious neurological condition affecting the bundle of nerve roots at the lower end of the spinal cord. The CE provides innervation to the lower limbs, and sphincter,controls the function of the bladder and distal bowel and sensation to the skin around the bottom and back passage<ref name=":0">Fraser s, Roberts L, Murphy E. Cauda Equina Syndrome: A Literature Review of Its Definition and Clinical Presentation. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 2009 90(11), pp.1964–1968. | |||

</ref>. | |||

< | CES occurs when the nerves below the spinal cord are compressed causing compromise to the bladder and bowel. The most common cause of CES is a prolapse of a lumbar disc but other conditions such as metastatic spinal cord compression can also cause CES<ref name=":0" />. | ||

There is no agreed definition of CES but the British Association of Spinal Surgeons (BASS) present a definition that is useful in clinical practice; | |||

'A patient presenting with acute back pain and/or leg pain...... with a suggestion of a disturbance of their bladder or bowel function and/or saddle sensory disturbance should be suspected of having a CES. Most of these patients will not have critical compression of the cauda equina. However, in the absence of reliably predictive symptoms and signs, there should be a low threshold for investigation with an emergency scan'<ref name=":4">Germon T, Ahuja,S, Casey A, Rai A. British Association of Spine Surgeons standards of care for cauda equina syndrome. The Spine Journal 2015 15 (3), pS2-S4. | |||

</ref>. | |||

==Classification== | |||

= | '''4 groups of patients have been classified according to their presentation :'''<ref name=":1">Todd, N V; Dickson, R A . Standards of care in cauda equina syndrome. British Journal of Neurosurgery. 2016, 30 (5), p518-522. | ||

</ref> | |||

'''CESS- Suspected''' | |||

Patients who do not have CES symptoms but who may go on to develop CES. It is important that patients understand the gravity of the condition and the importance of the time frame to seeking urgent medical attention. The use of a *credit card style patient information or a leaflet explaining what to look for and what to do should they develop symptoms is recommended. | |||

'''CESI- Incomplete''' | |||

Patients who present with urinary difficulties with a neurogenic origin, including loss of desire to void, poor stream, needing to strain to empty their bladder, and loss of urinary sensation. These patients could develop CESR and are a medical emergency and should have a surgical opinion urgently. | |||

'''CESR -Retention''' | |||

Patients who present with painless urinary retention and overflow incontinence; the bladder is no longer under executive control. An urgent surgical opinion is necessary | |||

'''CESC-Complete''' | |||

Patients who have objective loss of the cauda equina function, absent perineal sensation, a loose anus and paralysed bladder and bowel. {{#ev:youtube|MLnY_esmmhE|300}}<ref>CES UK. Presentation - A Neurological Perspective of Cauda Equina Syndrome . Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MLnY_esmmhE [last accessed 20/04/14]</ref> | |||

== Clinically Relevant Anatomy == | |||

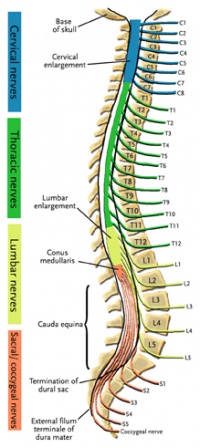

[[Image:Colored Spine.jpg|right|200px|Colored Spine]] | |||

The spinal cord ends around L1, consequently, the caudal nerve roots below the first lumbar root, form the cauda equina. The roots descend at an almost vertical angle to reach their corresponding foramina, gathered around the filum terminale within the spinal theca<ref name=":2">Standring, S (ED IN CHIEF) Grays Anatomy, the anatomical basis of clinical practice 40<sup>th</sup> edition Churchill Livingstone Elsevier, 2008. | |||

</ref>. The proximal portion of the cauda equina is said to be hypovascular hence more vulnerable if compressed <ref>Parke WW, Gammell K, Rothman RH. Arterial vascularization of the cauda equina. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1981; 63: 53–62. | |||

</ref>. The cauda equina roots have both a dorsal and ventral root. The ventral root provides motor fibres for the efferent pathway along with sympathetic fibres. The dorsal root is composed of afferent fibres for the transmission of sensation. The functions of those nerves are: | |||

* Sensory and motor fibres to the lower limbs. | |||

* Sensory innervation to the saddle area. | |||

* Voluntary control of the external anal and urinary sphincters. | |||

Aspects of anatomical features relating to saddle sensation, bladder, bowel and sexual function are discussed below; | |||

< | The first three sacral nerves, S1,2 and 3 supply multifidus and lateral cutaneous branches to the skin and fascia over the sacrum and part of the gluteal region. The 4th and 5th sacral nerves, S4 and 5, along with posterior primary ramus of the coccygeal nerve supply the skin and fascia around the coccyx. The pelvic splenic nerves to the pelvic viscera composed of parasympathetic fibres, travel in the ventral rami of S2,3 and 4. They then leave these nerves as they exit the anterior sacral foramina and pass to the pre-sacral tissue. Some pass to the pelvic viscera alongside the pelvic sympathetic supply and supply the urogenital organs and distal aspect of the large intestine. Others pass immediately into retroperitoneal tissue and into the mesentry of the sigmoid and descending colon <ref name=":2" />. The pudendal nerve supplies the perineum and arises from S2,3 and 4 with its terminal branches including the dorsal nerve of the penis or clitoris<ref>Brash J Jamieson E,(ed) Cunninghams Text book of Anatomy 7<sup>th</sup> edition. Oxford Medical Publications. 1937. | ||

</ref>. | |||

== Epidemiology == | |||

Cauda equina syndrome results from compression of the spinal cord and nerves/nerve roots arising from L1-L5 levels. | |||

* The most common cause of compression in 45% of CES is a herniated lumbar intervertebral disc. | |||

* Other causes include epidural abscess, spinal epidural hematoma, diskitis, tumor (either metastatic or a primary CNS cancer), trauma (particularly when there is retropulsion of bone fracture fragments), spinal stenosis and aortic obstruction. | |||

* Rare reported cases exist in which CES was associated with chiropractic manipulation, placement of interspinous devices, and thrombosis of the inferior vena cava.<ref>Rider IS, Marra EM. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537200/ Cauda Equina And Conus Medullaris Syndromes]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537200/ (last accessed 26.1.2020)</ref> | |||

== Clinical Presentation == | == Clinical Presentation == | ||

{{#ev:youtube|zJp3Q3jdd8I}}<ref>Physiotutors. Cauda Equina Syndrome | Signs & Symptoms. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zJp3Q3jdd8I</ref> | |||

* '''5 characteristic features of CES''' are consistently described in the literature and should form the basis of questions related to diagnosis<ref name=":1" />; | |||

#'''Bilateral neurogenic sciatica -''' Pain associated with the back and/ or unilateral/bilateral leg symptoms maybe present. | |||

#'''Reduced perineal sensation -''' Sensation loss in the perineum and saddle region is the most commonly reported symptom. | |||

#'''Altered bladder function leading to painless retention -''' Bladder dysfunction is the most commonly reported symptom and can range from increased frequency , difficulty in micturition, change in stream, incontinence and retention. | |||

#'''Loss of anal tone -''' loss or reduced anal tone may be evident if a patient reports bowel dysfunction. Bowel dysfunction may include incontinence, inability to control motions, inability to feel when the bowel is full and consequently overflow. | |||

#'''Loss of sexual function -''' Sexual dysfunction is not widely mentioned in the literature but is an important aspect that should be discussed with patients. | |||

== Risk Factors == | |||

== | * Disc herniations at L4-L5 or L5-S1.<ref name=":5">Finucane L, Downie A, Mercer CF, Greenhalgh S, Boissonnault WG, Pool-Goudzwaard A, et al. [https://www.jospt.org/doi/10.2519/jospt.2020.9971 International Framework for Red flags for Potential Serious Spinal Pathologies]. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy [Internet]. 2020 Jul 1;50(7):350–72.</ref> | ||

* Under 50 years old.<ref name=":5" /> | |||

* Obesity.<ref name=":5" /> | |||

* Recent lumbar spine surgical interventions.<ref name=":5" /> | |||

== Examination == | |||

==== Subjective examination ==== | |||

The difficulty with diagnosing serious spinal conditions early and the catastrophic outcomes of delayed diagnosis are widely documented <ref>Levack P, Graham J, Collie, D, et al. 2002. Don’t wait for a sensory level-listen to the symptoms: a prospective audit of the delays in diagnosis of malignant cord compression. Clin. Oncol. 2002;14: 472–480. | |||

</ref><ref>Markham D E.2004. Cauda equina syndrome: diagnosis, delay and litigation risk. Journal of Orthopaedic Medicine. 2004; 26: 102–105 | |||

</ref>. | |||

The subjective history is the most important aspect of the examination early in the disease process as the subtle and vague symptoms related to early Cauda Equina Syndrome need to be identified using clear methods of communication. | |||

* | Good communication skills allow us to gain an understanding of the patient’s world by achieving an understanding of what patients perceive is happening to them<ref name=":3">Swain J. Interpersonal communication. In: French, Sally, Sim, Julius (Eds.), Physiotherapy a Psychosocial Approach, 3rd ed. Edinburgh, pp. 205–219. 2004. | ||

</ref> . The important items to screen within the subjective history are [[Red Flags in Spinal Conditions|Red Flags]]. It is well recognized that the presence of Red and Yellow Flags are not mutually exclusive <ref>Gifford L. editor. Topical Issues in Pain 2. Biopsychosocial assessment. Relationships and pain. Falmouth, CNS Press.2000.</ref>. The clinical reasoning process essentially combines a [[Biopsychosocial Model|biopsychosocial assessment]] alongside this Red Flag screening to get a full true picture of the patient’s story and current clinical presentation. Establishing the history of the present condition in detail is key as timing is of paramount importance in this condition. | |||

* When the back and or leg pain started is significant but precisely when symptoms relating to parasympathetic supply began is vital; one hour, one day, one week, 15 years? There is no way of predicting who will progress from CESS to CESR and how quickly this may happen and so precise recording of the timing of chronology cannot be underestimated. | |||

* Establish if things are changing, better, episodic, worse or the same. Improving pain does not necessarily mean the condition is improving. Checking Red Flags and neurological status is important before this improved status can be assumed. Constant pain and night pain must be viewed along with all Red Flags with caution. | |||

* Establish the pattern of pain through 24 hours. Reference of pain and precise area of pins and needles and numbness must be identified and clearly documented. Aggravating and easing factors should be explored. Establish if these symptoms have been experienced before or are they different? | |||

* Has an MRI been performed with these current symptoms? This seems so obvious but can help with the clinical reasoning process. | |||

* What treatments have been tried including medication is helpful on a variety of levels. Many medications cause symptoms that masquerade as CES<ref>Woods E, Greenhalgh S, Selfe J (2015) Cauda Equina Syndrome and the challenge of diagnosis for physiotherapists: a review Physiotherapy Practice and Research. 2015;36:81-86 | |||

</ref>. This does not mean that symptoms can be ignored and attributed to drugs, however, medication could be contributing to the bladder, bowel and sexual dysfunction. Similarly, pain can cause retention. | |||

* Explore the patient’s medication regime and escalation up the analgesic ladder? Is medication being used appropriately and titrated correctly? This can give an indication of the severity of pain and its control. Establish the quality and intensity of pain e.g VAS. | |||

* What is the past medical history status; previous diagnosis of disc pathology or spinal stenosis for instance may be significant. Previous history of serious conditions such as cancer must be noted and may be important. Similarly many co-morbidities could masquerade as CES e.g. Diabetes, Multiple Sclerosis, Benign prostatic hyperplasia, pregnancy. | |||

* Has there been any recent or past spinal surgery and any history of osteoporosis; a retropulsed vertebral insufficiency fracture could cause CES. | |||

If CES/CES risk is suspected the subjective history must explore symptoms in even more detail. Tools and questions to use are covered in the next Research section. It is important that these questions are framed to highlight their gravity. The patient needs to recognise that the next questions are vital and accurate response of the utmost importance. | |||

'''Communication''' | |||

A Qualitative research study has identified that clear communication plays a pivotal role in identifying Cauda Equina Syndrome patient’s early to facilitate bringing these patients to the surgical team in a timely manner <ref>Greenhalgh S, Truman C, Webster V , Selfe J. 2016 Development of a toolkit for early identificationof cauda equina syndrome. Primary Health Care Research & Development. 2016;17:559-567. | |||

</ref>. Through this study it emerged that in order to identify CES patients early in the disease process to facilitate a timely surgical opinion one of the key problems was the use of language that reflected the patient’s own voice. The patient participants emphasised the need for clinicians to use language that they could understand during a clinical consultation, especially in the context of severe pain. A CES cue card for clinicians to use in the clinical consultation to enable the patient to focus on important questions was developed. It enables clinicians to frame the questions as important. The clinical cue card maps against a patient credit card using the same questions. This highlights symptoms to look out for and crucially timely action to take should symptoms develop. *The credit card could be used by the patient particularly in an emergency setting to help express the change in embarrassing and sensitive symptoms. | |||

* | <nowiki>*</nowiki>[https://macpweb.org/home/index.php?p=396 Download the patient credit card] <br> | ||

==== Physical examination ==== | |||

The physical examination should include: | |||

* | * a full neurological assessment to determine dermatomal sensory loss, myotomal weakness and reflex change. | ||

* Where a patient reports bilateral leg pain, signs of upper motor neuron involvement should be examined (babinski and clonus). For a comprehensive overview of neurological integrity testing the reader is referred to the following book 'Neuromusculoskeletal examination and assessment' <ref>Petty N, editor. Neuromusculoskeletal examination and assessment a handbook for therapists. Fourth edition. Churchill Livingstone. 2011.</ref>. | |||

* | * Where a patient reports sensory changes in the perineal area this should be tested to evaluate any sensory loss. | ||

* A digital rectal examination should be performed to assess any loss of anal sphincter tone. This should only be performed by an appropriately trained clinician. Reduced sensation of the perineum and/or anal tone is objective evidence of CESI and CESR but are likely to be normal in CESS<ref name=":1" />. | |||

* | |||

< | |||

== Diagnostic Procedures == | == Diagnostic Procedures == | ||

The diagnosis of cauda equina syndrome is based on the patients reported subjective history. Physical examination findings may help to confirm the diagnosis but should not be solely relied on. If CES is suspected the patient must undergo an MRI urgently to confirm the diagnosis. It is important to understand your locally agreed pathway to make sure there is no delay to diagnosis and where CES is confirmed, there is no delay to surgical intervention. | |||

<br>While MRI, coupled with patient history and examination, remains the diagnostic gold standard, it comes at a high cost with many patients demonstrating no concordant pathology.<ref name="Fairbank">Fairbank J. Et al. Does patient history and physical examination predict MRI proven cauda equina syndrome? Evidence based spine care journal 2011; 2(4): 27-33. [Level Of Evidence: 1]</ref>{{#ev:youtube|8rRq5QqoK3o|300}} | |||

== Key Evidence == | |||

Cauda equina syndrome is a grey area and there is no consensus on which signs and symptoms should be acted on. However it can have life changing consequences and it is important to act quickly if it is suspected. | |||

== | |||

< | == Litigation == | ||

The scale and impact of claims for negligence against clinicians treating people with CES is significant, and rising. Whilst it is difficult to accurately collate international statistics, there are robust data for the UK, which are presented below. These are taken from national agencies dealing with litigation against medical professionals (Medical Defence Union- MDU, and the National Health Service Litigation Authority-NHSLA) <ref>http://www.nhsla.com/Pages/Home.aspx</ref>. | |||

The | Taylor <ref>https://mdujournal.themdu.com/issue.../analysis-of-cauda-equina-syndrome-claims</ref> analysed claims made to the MDU between 2005 and 2016 related to CES. In that period there were 150 claims made-92% against GPs. The majority of these were successfully defended (70%) though the MDU paid out 350 000 pounds ($456,340) in legal costs. Over the same time period, £8 million ($10.4m) was paid out on settled claims, most of which were under £100 000 ($130 000). 4.5m of this was in solicitors’ fees. Around 12% of claims were for more than 500 000 pounds ($650 000). | ||

The NHSLA (2016) examined claims for CES from 2010-2015. Of the 293 cases identified, 232 were still under investigation and unsettled; 20 had settled with agreed damages; 41 had concluded with no damages awarded. Overall £25 million had been paid out. The survey identified that 70% of patients involved in claims were aged between 31-50. | |||

Other data suggests that average payouts for CES claims in the UK are around £336 000 ($436 800), with around £133 000 of that going to the patient and the remainder on legal costs. US data suggests average payouts are $549 427 (£422 636) | |||

Although not specifically focused on CES, a study by Taylor in 2014 of litigation cases in the USA against neurosurgeons, found that they were more likely to be sued following spinal surgery than cranial surgery, with the average claim being around $278 362. A similar study, relating to neurosurgical litigation in the UK <ref>Hamdan A, Strachan R D, Nath F, Coulter IC. Counting the cost of negligence in neurosurgery:Lessons to be learned from 10 years of Claims in the NHS. British Journal of Neurosurgery. 2015; 29:2:169-177.</ref>, found that the highest number of claims related to spinal surgery (44%) and that 87.5% of claims relating to CES were successful. | |||

It is clear that litigation for CES is only likely to increase, and equally clear that as treating healthcare professionals, we need to ensure that we examine patients fully and appropriately, that we warn, or “safety net” them where we have concerns, and that we have robust pathways in place to ensure rapid access to MRI scanning and spinal surgical specialists. | |||

== Clinical Bottom Line == | |||

Cauda equina syndrome is rare but can have life changing consequences if not acted upon in a timely manner. If surgical intervention is delayed irreversible damage can occur to the bladder, bowel and sexual function. | |||

'''Relevant symptoms include unilateral or bilateral radicular pain and/or dermatomal reduced sensation and/or myotomal weakness with any suggestion of change in bladder or bowel function however minor should be investigated<ref name=":1" />'''. | |||

Nothing is to be gained by delaying surgery and should be carried out as soon as is practically possible<ref name=":4" /><ref name=":1" />. | |||

'''Safety netting''' | |||

Not all patients with back pain will develop CES and it is not necessary to warn all patients. Those patients whom you suspect may go onto develop CES should be given the appropriate information and know what to do should they go on to develop symptoms. | |||

'''Communication''' | |||

Patients need to understand the relevance of the questions you ask as they may not fully appreciate the importance and subsequent consequences if not explained properly. | |||

'''Documentation''' | |||

It is important that a patients signs and symptoms are fully documented in accordance to your governing bodies standards of practice so there is a clear record of the patients journey. | |||

== | == Podcast == | ||

[https://anchor.fm/tpmpodcast/episodes/Session-65---Cauda-Equina-Syndrome-with-Chris-Mercer-e3u9kq?utm_source=listennotes.com&utm_campaign=Listen+Notes&utm_medium=website Cauda Equina Syndrome with Chris Mercer] | |||

& | |||

== References == | == References == | ||

<references /> | |||

[[Category: | [[Category:Primary Contact]] | ||

[[Category:Syndromes]] | |||

[[Category:Acute Care]] | |||

[[Category:Neurology]] | |||

Latest revision as of 11:26, 29 February 2024

Special Contribution - Laura Finucane, Sue Greenhalgh, Chris Mercer,

Original Editor - Laurie Fiegle and Tabitha Korona

Top Contributors - Laura Finucane, Tabitha Korona, Scott Buxton, Admin, Laura Ritchie, Thibaut Seys, Laurie Fiegle, Jolien Wauters, Evan Thomas, Kim Jackson, Margo De Mesmaeker, Rachael Lowe, Claire Knott, Lucinda hampton, Naomi O'Reilly, WikiSysop, Simisola Ajeyalemi, Shaimaa Eldib, Jess Bell, Olajumoke Ogunleye, Saud Alghamdi, Garima Gedamkar, Kai A. Sigel, 127.0.0.1, Karen Wilson, Tony Lowe and Candace Goh

Definition[edit | edit source]

Cauda equina syndrome (CES) is a rare but serious neurological condition affecting the bundle of nerve roots at the lower end of the spinal cord. The CE provides innervation to the lower limbs, and sphincter,controls the function of the bladder and distal bowel and sensation to the skin around the bottom and back passage[1].

CES occurs when the nerves below the spinal cord are compressed causing compromise to the bladder and bowel. The most common cause of CES is a prolapse of a lumbar disc but other conditions such as metastatic spinal cord compression can also cause CES[1].

There is no agreed definition of CES but the British Association of Spinal Surgeons (BASS) present a definition that is useful in clinical practice;

'A patient presenting with acute back pain and/or leg pain...... with a suggestion of a disturbance of their bladder or bowel function and/or saddle sensory disturbance should be suspected of having a CES. Most of these patients will not have critical compression of the cauda equina. However, in the absence of reliably predictive symptoms and signs, there should be a low threshold for investigation with an emergency scan'[2].

Classification[edit | edit source]

4 groups of patients have been classified according to their presentation :[3]

CESS- Suspected

Patients who do not have CES symptoms but who may go on to develop CES. It is important that patients understand the gravity of the condition and the importance of the time frame to seeking urgent medical attention. The use of a *credit card style patient information or a leaflet explaining what to look for and what to do should they develop symptoms is recommended.

CESI- Incomplete

Patients who present with urinary difficulties with a neurogenic origin, including loss of desire to void, poor stream, needing to strain to empty their bladder, and loss of urinary sensation. These patients could develop CESR and are a medical emergency and should have a surgical opinion urgently.

CESR -Retention

Patients who present with painless urinary retention and overflow incontinence; the bladder is no longer under executive control. An urgent surgical opinion is necessary

CESC-Complete

Patients who have objective loss of the cauda equina function, absent perineal sensation, a loose anus and paralysed bladder and bowel.

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

The spinal cord ends around L1, consequently, the caudal nerve roots below the first lumbar root, form the cauda equina. The roots descend at an almost vertical angle to reach their corresponding foramina, gathered around the filum terminale within the spinal theca[5]. The proximal portion of the cauda equina is said to be hypovascular hence more vulnerable if compressed [6]. The cauda equina roots have both a dorsal and ventral root. The ventral root provides motor fibres for the efferent pathway along with sympathetic fibres. The dorsal root is composed of afferent fibres for the transmission of sensation. The functions of those nerves are:

- Sensory and motor fibres to the lower limbs.

- Sensory innervation to the saddle area.

- Voluntary control of the external anal and urinary sphincters.

Aspects of anatomical features relating to saddle sensation, bladder, bowel and sexual function are discussed below;

The first three sacral nerves, S1,2 and 3 supply multifidus and lateral cutaneous branches to the skin and fascia over the sacrum and part of the gluteal region. The 4th and 5th sacral nerves, S4 and 5, along with posterior primary ramus of the coccygeal nerve supply the skin and fascia around the coccyx. The pelvic splenic nerves to the pelvic viscera composed of parasympathetic fibres, travel in the ventral rami of S2,3 and 4. They then leave these nerves as they exit the anterior sacral foramina and pass to the pre-sacral tissue. Some pass to the pelvic viscera alongside the pelvic sympathetic supply and supply the urogenital organs and distal aspect of the large intestine. Others pass immediately into retroperitoneal tissue and into the mesentry of the sigmoid and descending colon [5]. The pudendal nerve supplies the perineum and arises from S2,3 and 4 with its terminal branches including the dorsal nerve of the penis or clitoris[7].

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

Cauda equina syndrome results from compression of the spinal cord and nerves/nerve roots arising from L1-L5 levels.

- The most common cause of compression in 45% of CES is a herniated lumbar intervertebral disc.

- Other causes include epidural abscess, spinal epidural hematoma, diskitis, tumor (either metastatic or a primary CNS cancer), trauma (particularly when there is retropulsion of bone fracture fragments), spinal stenosis and aortic obstruction.

- Rare reported cases exist in which CES was associated with chiropractic manipulation, placement of interspinous devices, and thrombosis of the inferior vena cava.[8]

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

- 5 characteristic features of CES are consistently described in the literature and should form the basis of questions related to diagnosis[3];

- Bilateral neurogenic sciatica - Pain associated with the back and/ or unilateral/bilateral leg symptoms maybe present.

- Reduced perineal sensation - Sensation loss in the perineum and saddle region is the most commonly reported symptom.

- Altered bladder function leading to painless retention - Bladder dysfunction is the most commonly reported symptom and can range from increased frequency , difficulty in micturition, change in stream, incontinence and retention.

- Loss of anal tone - loss or reduced anal tone may be evident if a patient reports bowel dysfunction. Bowel dysfunction may include incontinence, inability to control motions, inability to feel when the bowel is full and consequently overflow.

- Loss of sexual function - Sexual dysfunction is not widely mentioned in the literature but is an important aspect that should be discussed with patients.

Risk Factors[edit | edit source]

- Disc herniations at L4-L5 or L5-S1.[10]

- Under 50 years old.[10]

- Obesity.[10]

- Recent lumbar spine surgical interventions.[10]

Examination[edit | edit source]

Subjective examination[edit | edit source]

The difficulty with diagnosing serious spinal conditions early and the catastrophic outcomes of delayed diagnosis are widely documented [11][12].

The subjective history is the most important aspect of the examination early in the disease process as the subtle and vague symptoms related to early Cauda Equina Syndrome need to be identified using clear methods of communication.

Good communication skills allow us to gain an understanding of the patient’s world by achieving an understanding of what patients perceive is happening to them[13] . The important items to screen within the subjective history are Red Flags. It is well recognized that the presence of Red and Yellow Flags are not mutually exclusive [14]. The clinical reasoning process essentially combines a biopsychosocial assessment alongside this Red Flag screening to get a full true picture of the patient’s story and current clinical presentation. Establishing the history of the present condition in detail is key as timing is of paramount importance in this condition.

- When the back and or leg pain started is significant but precisely when symptoms relating to parasympathetic supply began is vital; one hour, one day, one week, 15 years? There is no way of predicting who will progress from CESS to CESR and how quickly this may happen and so precise recording of the timing of chronology cannot be underestimated.

- Establish if things are changing, better, episodic, worse or the same. Improving pain does not necessarily mean the condition is improving. Checking Red Flags and neurological status is important before this improved status can be assumed. Constant pain and night pain must be viewed along with all Red Flags with caution.

- Establish the pattern of pain through 24 hours. Reference of pain and precise area of pins and needles and numbness must be identified and clearly documented. Aggravating and easing factors should be explored. Establish if these symptoms have been experienced before or are they different?

- Has an MRI been performed with these current symptoms? This seems so obvious but can help with the clinical reasoning process.

- What treatments have been tried including medication is helpful on a variety of levels. Many medications cause symptoms that masquerade as CES[15]. This does not mean that symptoms can be ignored and attributed to drugs, however, medication could be contributing to the bladder, bowel and sexual dysfunction. Similarly, pain can cause retention.

- Explore the patient’s medication regime and escalation up the analgesic ladder? Is medication being used appropriately and titrated correctly? This can give an indication of the severity of pain and its control. Establish the quality and intensity of pain e.g VAS.

- What is the past medical history status; previous diagnosis of disc pathology or spinal stenosis for instance may be significant. Previous history of serious conditions such as cancer must be noted and may be important. Similarly many co-morbidities could masquerade as CES e.g. Diabetes, Multiple Sclerosis, Benign prostatic hyperplasia, pregnancy.

- Has there been any recent or past spinal surgery and any history of osteoporosis; a retropulsed vertebral insufficiency fracture could cause CES.

If CES/CES risk is suspected the subjective history must explore symptoms in even more detail. Tools and questions to use are covered in the next Research section. It is important that these questions are framed to highlight their gravity. The patient needs to recognise that the next questions are vital and accurate response of the utmost importance.

Communication

A Qualitative research study has identified that clear communication plays a pivotal role in identifying Cauda Equina Syndrome patient’s early to facilitate bringing these patients to the surgical team in a timely manner [16]. Through this study it emerged that in order to identify CES patients early in the disease process to facilitate a timely surgical opinion one of the key problems was the use of language that reflected the patient’s own voice. The patient participants emphasised the need for clinicians to use language that they could understand during a clinical consultation, especially in the context of severe pain. A CES cue card for clinicians to use in the clinical consultation to enable the patient to focus on important questions was developed. It enables clinicians to frame the questions as important. The clinical cue card maps against a patient credit card using the same questions. This highlights symptoms to look out for and crucially timely action to take should symptoms develop. *The credit card could be used by the patient particularly in an emergency setting to help express the change in embarrassing and sensitive symptoms.

*Download the patient credit card

Physical examination[edit | edit source]

The physical examination should include:

- a full neurological assessment to determine dermatomal sensory loss, myotomal weakness and reflex change.

- Where a patient reports bilateral leg pain, signs of upper motor neuron involvement should be examined (babinski and clonus). For a comprehensive overview of neurological integrity testing the reader is referred to the following book 'Neuromusculoskeletal examination and assessment' [17].

- Where a patient reports sensory changes in the perineal area this should be tested to evaluate any sensory loss.

- A digital rectal examination should be performed to assess any loss of anal sphincter tone. This should only be performed by an appropriately trained clinician. Reduced sensation of the perineum and/or anal tone is objective evidence of CESI and CESR but are likely to be normal in CESS[3].

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

The diagnosis of cauda equina syndrome is based on the patients reported subjective history. Physical examination findings may help to confirm the diagnosis but should not be solely relied on. If CES is suspected the patient must undergo an MRI urgently to confirm the diagnosis. It is important to understand your locally agreed pathway to make sure there is no delay to diagnosis and where CES is confirmed, there is no delay to surgical intervention.

While MRI, coupled with patient history and examination, remains the diagnostic gold standard, it comes at a high cost with many patients demonstrating no concordant pathology.[18]

Key Evidence[edit | edit source]

Cauda equina syndrome is a grey area and there is no consensus on which signs and symptoms should be acted on. However it can have life changing consequences and it is important to act quickly if it is suspected.

Litigation[edit | edit source]

The scale and impact of claims for negligence against clinicians treating people with CES is significant, and rising. Whilst it is difficult to accurately collate international statistics, there are robust data for the UK, which are presented below. These are taken from national agencies dealing with litigation against medical professionals (Medical Defence Union- MDU, and the National Health Service Litigation Authority-NHSLA) [19].

Taylor [20] analysed claims made to the MDU between 2005 and 2016 related to CES. In that period there were 150 claims made-92% against GPs. The majority of these were successfully defended (70%) though the MDU paid out 350 000 pounds ($456,340) in legal costs. Over the same time period, £8 million ($10.4m) was paid out on settled claims, most of which were under £100 000 ($130 000). 4.5m of this was in solicitors’ fees. Around 12% of claims were for more than 500 000 pounds ($650 000).

The NHSLA (2016) examined claims for CES from 2010-2015. Of the 293 cases identified, 232 were still under investigation and unsettled; 20 had settled with agreed damages; 41 had concluded with no damages awarded. Overall £25 million had been paid out. The survey identified that 70% of patients involved in claims were aged between 31-50.

Other data suggests that average payouts for CES claims in the UK are around £336 000 ($436 800), with around £133 000 of that going to the patient and the remainder on legal costs. US data suggests average payouts are $549 427 (£422 636)

Although not specifically focused on CES, a study by Taylor in 2014 of litigation cases in the USA against neurosurgeons, found that they were more likely to be sued following spinal surgery than cranial surgery, with the average claim being around $278 362. A similar study, relating to neurosurgical litigation in the UK [21], found that the highest number of claims related to spinal surgery (44%) and that 87.5% of claims relating to CES were successful.

It is clear that litigation for CES is only likely to increase, and equally clear that as treating healthcare professionals, we need to ensure that we examine patients fully and appropriately, that we warn, or “safety net” them where we have concerns, and that we have robust pathways in place to ensure rapid access to MRI scanning and spinal surgical specialists.

Clinical Bottom Line[edit | edit source]

Cauda equina syndrome is rare but can have life changing consequences if not acted upon in a timely manner. If surgical intervention is delayed irreversible damage can occur to the bladder, bowel and sexual function.

Relevant symptoms include unilateral or bilateral radicular pain and/or dermatomal reduced sensation and/or myotomal weakness with any suggestion of change in bladder or bowel function however minor should be investigated[3].

Nothing is to be gained by delaying surgery and should be carried out as soon as is practically possible[2][3].

Safety netting

Not all patients with back pain will develop CES and it is not necessary to warn all patients. Those patients whom you suspect may go onto develop CES should be given the appropriate information and know what to do should they go on to develop symptoms.

Communication

Patients need to understand the relevance of the questions you ask as they may not fully appreciate the importance and subsequent consequences if not explained properly.

Documentation

It is important that a patients signs and symptoms are fully documented in accordance to your governing bodies standards of practice so there is a clear record of the patients journey.

Podcast[edit | edit source]

Cauda Equina Syndrome with Chris Mercer

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Fraser s, Roberts L, Murphy E. Cauda Equina Syndrome: A Literature Review of Its Definition and Clinical Presentation. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 2009 90(11), pp.1964–1968.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Germon T, Ahuja,S, Casey A, Rai A. British Association of Spine Surgeons standards of care for cauda equina syndrome. The Spine Journal 2015 15 (3), pS2-S4.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Todd, N V; Dickson, R A . Standards of care in cauda equina syndrome. British Journal of Neurosurgery. 2016, 30 (5), p518-522.

- ↑ CES UK. Presentation - A Neurological Perspective of Cauda Equina Syndrome . Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MLnY_esmmhE [last accessed 20/04/14]

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Standring, S (ED IN CHIEF) Grays Anatomy, the anatomical basis of clinical practice 40th edition Churchill Livingstone Elsevier, 2008.

- ↑ Parke WW, Gammell K, Rothman RH. Arterial vascularization of the cauda equina. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1981; 63: 53–62.

- ↑ Brash J Jamieson E,(ed) Cunninghams Text book of Anatomy 7th edition. Oxford Medical Publications. 1937.

- ↑ Rider IS, Marra EM. Cauda Equina And Conus Medullaris Syndromes. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537200/ (last accessed 26.1.2020)

- ↑ Physiotutors. Cauda Equina Syndrome | Signs & Symptoms. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zJp3Q3jdd8I

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Finucane L, Downie A, Mercer CF, Greenhalgh S, Boissonnault WG, Pool-Goudzwaard A, et al. International Framework for Red flags for Potential Serious Spinal Pathologies. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy [Internet]. 2020 Jul 1;50(7):350–72.

- ↑ Levack P, Graham J, Collie, D, et al. 2002. Don’t wait for a sensory level-listen to the symptoms: a prospective audit of the delays in diagnosis of malignant cord compression. Clin. Oncol. 2002;14: 472–480.

- ↑ Markham D E.2004. Cauda equina syndrome: diagnosis, delay and litigation risk. Journal of Orthopaedic Medicine. 2004; 26: 102–105

- ↑ Swain J. Interpersonal communication. In: French, Sally, Sim, Julius (Eds.), Physiotherapy a Psychosocial Approach, 3rd ed. Edinburgh, pp. 205–219. 2004.

- ↑ Gifford L. editor. Topical Issues in Pain 2. Biopsychosocial assessment. Relationships and pain. Falmouth, CNS Press.2000.

- ↑ Woods E, Greenhalgh S, Selfe J (2015) Cauda Equina Syndrome and the challenge of diagnosis for physiotherapists: a review Physiotherapy Practice and Research. 2015;36:81-86

- ↑ Greenhalgh S, Truman C, Webster V , Selfe J. 2016 Development of a toolkit for early identificationof cauda equina syndrome. Primary Health Care Research & Development. 2016;17:559-567.

- ↑ Petty N, editor. Neuromusculoskeletal examination and assessment a handbook for therapists. Fourth edition. Churchill Livingstone. 2011.

- ↑ Fairbank J. Et al. Does patient history and physical examination predict MRI proven cauda equina syndrome? Evidence based spine care journal 2011; 2(4): 27-33. [Level Of Evidence: 1]

- ↑ http://www.nhsla.com/Pages/Home.aspx

- ↑ https://mdujournal.themdu.com/issue.../analysis-of-cauda-equina-syndrome-claims

- ↑ Hamdan A, Strachan R D, Nath F, Coulter IC. Counting the cost of negligence in neurosurgery:Lessons to be learned from 10 years of Claims in the NHS. British Journal of Neurosurgery. 2015; 29:2:169-177.