Calcaneal Fractures: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 34: | Line 34: | ||

For more detailed anatomy see [[Ankle and Foot]] | For more detailed anatomy see [[Ankle and Foot]] | ||

== Epidemiology/ | == Epidemiology/Etiology == | ||

Calcaneal fractures correspond to approximately 1% to 2% of all the fractures of the human body and constitute nearly 60% of tarsal bones fractures. They generally follow high-energy axial traumas, such as fall from height or motor accidents. | Calcaneal fractures correspond to approximately 1% to 2% of all the fractures of the human body and constitute nearly 60% of tarsal bones fractures. They generally follow high-energy axial traumas, such as fall from height or motor accidents. | ||

Revision as of 07:08, 17 June 2020

Original Editor -

Top Contributors - Hajar Abdelhadji, Roxann Musimu , Dylan Van Calck

Definition / Description[edit | edit source]

A calcaneus fracture is a heel bone fracture. The calcaneus, the largest tarsal bone, is specifically designed to support the body and endure a great degree of force. It is situated at the lower and back part of the foot, forming the heel.[1]

Together with the talus, the calcaneus forms the subtalar joint. This joint allows inversion and eversion of the foot. The midtarsal joint is comprised of two joints: The talocalcaneonavicular and the calcaneocuboid joint. [2]

The calcaneus has four important functions:

- Acts as a foundation and support for the body’s weight

- Supports the lateral column of the foot and acts as the main articulation for inversion/eversion

- Acts as a lever arm for the gastrocnemius muscle complex

- Makes normal walking possible

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

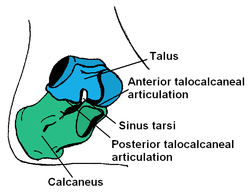

A sound understanding of the anatomy of the calcaneus is essential in determining the patterns of injury and treatment goals and options. The bony architecture of the calcaneus is that of an irregularly shaped rectangle with four facets, one of which articulates anteriorly with the cuboid bone and three of which (the anterior, middle, and posterior facets) articulate superiorly with the talus.[3]

The superior surfaces articulate with the talus

- Posterior facet - Separated from the middle and anterior facets by a groove that runs posteromedially, know as the calcaneal sulcus. The canal formed between the calcaneal sulcus and talus is called the sinus tarsi.

- Middle calcaneal facet - Supported by the sustenaculum tali and articulates with the middle facet of the talus.

- Anterior calcaneal facet -articulates with the anterior talar facet and is supported by the calcaneal beak.

The triangular anterior surface of the calcaneus articulates with the cuboid

The lateral surfaces

- The lateral surface is flat and subcutaneous, with a central peroneal tubercle for the attachment of the calcaneofibular ligament centrally. The lateral talocalcaneal ligament attaches anterosuperior to the peroneal tubercle.

These anatomic landmarks are important because fractures associated with these areas may cause tendon injury[1]

For more detailed anatomy see Ankle and Foot

Epidemiology/Etiology[edit | edit source]

Calcaneal fractures correspond to approximately 1% to 2% of all the fractures of the human body and constitute nearly 60% of tarsal bones fractures. They generally follow high-energy axial traumas, such as fall from height or motor accidents.

According to the current literature, 60% to 75% of these fractures are considered to be displaced and intra-articular, which evidences the difficulty of the treatment. They can cause great disability due to pain and chronic stiffness, in addition to hindfoot deformities. These fractures are characterized clinically by poor functional results due to their complexity.

Approximately 80% to 90% of the calcaneal fractures happen in males between 21 and 40 years, mostly in industrial workers. Several authors have reported that the rehabilitation of these fractures can take from nine months to several years, which implicates a great economic burden on society.

Since the early 1980s, the treatment of choice for displaced and intra-articular calcaneal fractures was an open reduction with internal fixation; however, soft tissue complications, such as surgical dehiscence and infection, can occur in up to 30% of the patients.

In an attempt to reduce complication rates, new surgical techniques emerged, such as minimally invasive incision and percutaneous fixation, which cause less injury to the tissues and reduce the incidence of soft tissue complications.

Despite the modern surgical techniques and the considerable number of studies in the literature, calcaneal fractures and their best treatment method remain an enigma for orthopaedic surgeons. [4][5]

Mechanism of Injury / Pathological Process[edit | edit source]

Calcaneal fractures occur rarely. They only consist of 1,2% of all relatively rare injuries. The calcaneus is the most frequently fractured tarsal bone. Calcaneal fractures are mostly the result of a traumatic incident and high impact situation. The greater part of fractures (71,5%)[6] are sustained in falls from a height from usually 6 feet or more, a motor vehicle accident. The small amount of 18.8% of fractures occurred in the workplace. Calcaneal fractures can also occur with less severe accidents like an ankle sprain or a stress fracture.

Mostly, injuries occur in isolation. Most seen concomitant injuries were lower limb (13.2%) or spinal injuries (6.3%).

Calcaneal fractures can be extra-articular or intra-articular. The extra-articular fractures represent 60% of the calcaneal fractures in children and their incidence has been reported to be 25-40% of adult calcaneal fractures. They don’t involve the joint. according to the mechanism of injury, they can be classified as compression or avulsion fractures. They can also be categorized according to their location in the calcaneus. [7]

Intra-articular fractures do include the joint and have a lower prognosis and are more difficult to recover from. This type of fractures can be categorized into four different types according to Sanders[7]. With type II being non-displaced intra-articular fractures. Type II being two-part fractures which can be divided in Type IIa, IIb and IIc. Type III fractures which can also be divided into IIIa, IIIb and IIIc and usually have a depressed articular segment. Type IIII represents a four-part or very comminuted fracture.[7]

Characteristics / Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

- There are certain characteristics of a calcaneal fracture:

- Sudden pain in the heel, most importantly pressure pain.

- Swelling in the heel area

- Bruising of the heel and ankle

- Generalized pain in the heel area that usually develops slowly (over several days to weeks): typically for stress fractures

- Oedema

- A hematoma or pattern of ecchymosis extending distally to the sole of the foot.

- Deformity of the heel or plantar arch: Secondary to the displacement of the lateral calcaneal border outward, there is a possible widening or broadening of the heel.

- Inability or difficulty to bear weight on the affected side

- Limited or absent inversion / eversion of the foot

- Decreased Böhler or “tuber-joint” angle

- CT scan: Diverse views, both axial and coronal views can classify the degree of injury to the posterior facet and lateral calcaneal wall.

- X-rays or Radiographs:

- Axial x-ray: Determines primary fracture line and displays the body, tuberosity, middle and posterior facets

- Lateral x-ray: Determines Böhler angle

- Oblique / Broden’s view: Determines the degree of displacement of the primary fracture line

- Heel tenderness

- Difficulty walking:

- Inability to walk

- Inability to move the foot

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

- Heel pain

- Baxter's nerve entrapment: An entrapment of the recurrent branch of the posterior tibial nerve

- Calcaneal spurs

- Plantar fasciitis: Plantar fascial pain is specific to the bottom of the heel. An MRI can be used to differentiate a calcaneal fracture from plantar fascitis.

- Retrocalcaneal bursitis: This is the formation and inflammation of a bursa at the back of the heel between the heel bone and Achilles Tendon. Also called Albert's Disease.

- Rheumatoid Arthritis

- Septic Arthritis

- Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome: The pain of this syndrome doesn’t decrease with rest. Other symptoms are numbness or tingling of the toes.

- Ankle instability[8]

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

- Pain - Most importantly pressure pain, or pain elicited when providing pressure to the calcaneus by holding the heel of the patient’s foot and gently squeezing [9]

- Oedema

- Ecchymosis - A hematoma or pattern of ecchymosis extending distally to the sole of the foot is specific for calcaneal fractures and is known as the Mondor sign

- Deformity of the heel or plantar arch - Widening or broadening of the heel is seen secondary to the displacement of the lateral calcaneal border outward and accompanying oedema

- Inability to or difficulty weight-bearing on the affected side[7]

- Limited or absent inversion/eversion of the foot [4]

- Decreased Bohler or “tuber-joint” angle - In normal anatomical alignment an angle of 25-40 degrees exists between the upper border of the calcaneal tuberosity and a line connecting the anterior and posterior articulating surfaces. With calcaneal fractures, this angle becomes smaller, straighter, and can even reverse.

- CT scan (both axial and coronal views) to classify the degree of injury to the posterior facet and lateral calcaneal wall[5]

- X-rays or Radiographs:

- Axial - Determines primary fracture line and displays the body, tuberosity, middle and posterior facets

- Lateral - Determines Bohler angle

- Oblique/Broden’s view - Displays the degree of displacement of the primary fracture line.

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

Lower Extremity Functional Scale (LEFS) - this measures "patients' initial function, ongoing progress, and outcome" for a wide range of lower-extremity conditions.

Foot and Ankle Ability Measure (FAAM) - this a self-report outcome instrument developed to assess physical function for individuals with foot and ankle related impairments. This self-report outcome instrument is available in English, German, French and Persian. The Foot and Ankle Ability Measure is a 29-item questionnaire divided into two subscales: the Foot and Ankle Ability Measure, 21-item Activities of Daily Living Subscale and the Foot and Ankle Ability Measure, 8-item Sports Subscale. The Sports subscale assesses more difficult tasks that are essential to sport, it is a population-specific subscale designed for athletes.

Examination[edit | edit source]

To diagnose and evaluate a calcaneal fracture, the foot and ankle surgeon will ask questions about how the injury occurred, examine the affected foot and ankle and order x-rays. In addition, advanced imaging tests such as CT-scans are commonly required after a fracture. These provide more detailed, cross-sectional images of your foot.[10]

During the examination, a lot of different symptoms can be seen. The most obvious ones are pain, bruising, swelling, heel deformity and an inability of the patient to put weight on the heel or walk. Still, medical imaging should be the main way to diagnose a calcaneal fracture.[7]

The physiotherapist will examine the ankle to see if the skin was damaged or punctured from the injury. He will check for a pulse to see if there is a sufficient blood supply at the injured area. Also, he should check if the patient can move his toes and feel at the bottom of his foot to determine if there are any other injuries that occurred with the calcaneal fracture. Other techniques like squeezing the heel causes pain over the calcaneal protuberances. A thorough neurovascular examination is also essential.[11]

Questionnaires [edit | edit source]

One of the most used outcome measures for patients is the VAS-scale. This can be used to determine how the patient lives with his injury. We can measure the pain level before and after treatment. This can be useful to determine the efficacy of treatment.[12]

Medical Management / Interventions[edit | edit source]

Treatment of calcaneal fractures depends on the type of fracture and the extent of the injury. There is no universal treatment or surgical approach to all displaced intra-articular calcaneal fractures. The choice of treatment must be based on the characteristics of the patient and on the type of fracture.

Operative Care[edit | edit source]

For the majority of patients, surgery is the correct form of treatment[5]. The goal of surgery is to restore the correct size and structure of the heel. Intra-articular fractures are often treated operatively. This is possible by performing an open reduction and internal fixation of the fracture. These procedures are performed through an incision on the outside of the heel. The calcaneus is put together and held in place with a metal plate and multiple screws. This procedure decreases the possibility of developing arthritis and maximizes the potential for inversion and eversion of the foot. Extra-articular fractures are generally treated conservatively.

Non-Operative Care[edit | edit source]

Nonoperative management is preferable when there is no impingement of the peroneal tendons and the fracture segments are not displaced (or are displaced less than 2 mm). Nonoperative care is also recommended when, despite the presence of a fracture, proper weight-bearing alignment has been adequately maintained and articulating surfaces are not disturbed. Extra-articular fractures are generally treated conservatively. Patients who are over the age of 50 years old or who have pre-existing health conditions, such as diabetes or peripheral vascular disease, are also commonly treated using nonoperative techniques. Patients receiving nonoperative management. [13][14]

R.I.C.E[edit | edit source]

- Rest: The affected foot must rest and the patient is not allowed to use the foot. This is to allow the fracture to heal.

- Ice: Several times a day the patient has an ice treatment to reduce inflammation, swelling and pain.

- Compression: Bandage / Compression stocking

- Elevation: The initial management is to reduce the swelling with rest in bed with the foot slightly above heart level.

Immobilisation[edit | edit source]

Partial or complete immobilisation is used if the fracture has not displaced the bone. Usually a cast is used to keep the fractured bone from moving. In the cast, the ankle is in neutral position and sometimes in slight eversion. To avoid weight bearing, crutches may be needed.

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

After the surgery, active range of motion exercises may be practiced with small amounts of movement for all joints of the foot and ankle. These exercises are used to maintain and regain the ankle joint movement. When needed for the involved lower extremity, the patient may continue with elevation, icing and compression. During the therapy, the patient will progress to gradual weight bearing. Patients may find this very difficult and painful. The physiotherapist conducts joint mobilisation to all hypomobile joints.

During the treatment, progressive resisted strengthening of the gastrocnemius muscles is done by weighted exercises, toe-walking, ascending and descending stairs and plyometric exercises. When the fracture is healed, the physiotherapist will progress the weight bearing in more stressful situations. This therapy consists of gait instruction and balance practice on different surfaces.

Acute Stage[edit | edit source]

Immobilization. A cast, splint, or brace will hold the bones in your foot in proper position while they heal. You may have to wear a cast for 6 to 8 weeks — or possibly longer. During this time, you will not be able to put any weight on your foot until the bone is completely healed.[10]

Pre-Surgery[edit | edit source]

Initial stability is essential for open reduction internal fixation of intraarticular calcaneal fractures.

Preoperative revalidation consist on:

• Immediate elevation of the affected foot to reduce swelling

• Compression such as foot pump, intermittent compression devices or compression wraps.

• ICE

• Instructions for using wheelchair, bed transfers, or crutches.[14][15]

Post-Surgery[edit | edit source]

Both the progression of nonoperative and postoperative management of calcaneal fractures include traditional immobilization and early motion rehabilitation protocols. In fact, the traditional immobilization protocols of nonoperative and postoperative management are similar, and are thereby combined in the progression below. [16] Phases II and III of traditional and early motion rehabilitation protocols after nonoperative or postoperative care are comparable as well and are described together below. [7][17]

Phase I for Traditional Immobilization and Rehabilitation following Nonoperative and Postoperative Management: Weeks 1-4[edit | edit source]

Goals:

- Control oedema and pain

- Prevent extension of fracture or loss of surgical stabilization

- Minimize loss of function and cardiovascular endurance

Intervention:

- Cast with the ankle in neutral and sometimes slight eversion,

- Elevation

- Ice

- After 2-4 days, instruct in non-weight bearing ambulation utilizing crutches or walker

- Instruct in wheelchair use with an appropriate sitting schedule to limit time involved extremity spends in dependent-gravity position

- Instruct in comprehensive exercise and cardiovascular program utilizing upper extremities and uninvolved lower extremity

Phase II for Traditional Immobilization/Early Mobilization and Rehabilitation following Nonoperative and Postoperative Management: Weeks 5-8[edit | edit source]

Goals:

- Control remaining or residual oedema and pain

- Prevent re-injury or complication of fracture by progressing weight-bearing safely

- Prevent contracture and regain motion at ankle/foot joints

- Minimize loss of function and cardiovascular endurance

Intervention:

- Continued elevation, icing, and compression as needed for involved lower extremity

- After 6-8 weeks, instruct in partial-weight bearing ambulation utilizing crutches or walker

- Initiate vigorous exercise and range of motion to regain and maintain motion at all joints: tibiotalar, subtalar, midtarsal, and toe joints, including active range of motion in large amounts of movement and progressive isometric or resisted exercises

- Progress and monitor comprehensive upper extremity and cardiovascular program

Phase III for Traditional Immobilization/Early Mobilization and Rehabilitation following Nonoperative and Postoperative Management: Weeks 9-12[edit | edit source]

Goals:

- Progress weight-bearing status

- Normal gait on all surfaces

- Restore full range of motion

- Restore full strength

- Allow return to previous work status

Intervention:

- After 9-12 weeks, instruct in normal full-weight bearing ambulation with the appropriate assistive device as needed

- Progress and monitor the subtalar joint’s ability to adapt for ambulation on all surfaces, including graded and uneven surfaces

- Joint mobilization to all hypomobile joints including: tibiotalar, subtalar, midtarsal, and to toe joints

- Soft tissue mobilization to hypomobile tissues of the gastrocnemius complex, plantar fascia, or other appropriate tissues

- Progressive resisted strengthening of gastrocnemius complex through the use of pulleys, weighted exercise, toe-walking ambulation, ascending/descending stairs, skipping or other plyometric exercise, pool exercises, and other climbing activities

- Work hardening program or activities to allow return to work between 13- 52 weeks

Resources[edit | edit source]

http://ezinearticles.com/?Rehabilitation-After-Calcaneal-Fractures&id=4082480

http://orthopedics.about.com/od/footanklefractures/a/calcaneus.htm

http://xnet.kp.org/socal_rehabspecialists/ptr_library/09FootRegion/31Foot-CalcanealFracture.pdf

http://www.healthstatus.com/articles/Calcaneal_Fractures.html

Clinical Bottom Line[edit | edit source]

Calcaneal fractures can be divided into two groups: intra-articular en extra-articular calcaneal fractures. Intra-articular fractures have a lower prognosis. To determine the kind of fracture and if there is a fracture, medical imagery is needed. The rehabilitation programme consists of 3 stages postoperatively and are very important to enhance recovery.

Presentations[edit | edit source]

| fckLRImage:calcaneal_fracture_presentation.png|200px|border|left|fckLRrect 0 0 830 452 <a href="http://prezi.com/htzzh_lneqpu/calcaneal-fractures/">[n]</a>fckLRdesc nonefckLR | <a href="http://prezi.com/htzzh_lneqpu/calcaneal-fractures/">Calcaneal Fractures</a>

This presentation, created by Alice Thompson, provides an interactive insight into presentation, causes and types of calcaneal fractures as well as the evidence base for treatment options. <a href="http://prezi.com/htzzh_lneqpu/calcaneal-fractures/">Calcaneal Fractures/ View the presentation</a> |

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Daftary A, Haims AH, Baumgaertner MR. Fractures of the calcaneus: a review with emphasis on CT. Radiographics. 2005 Sep;25(5):1215-26.

- ↑ Badillo K, Pacheco JA, Padua SO, Gomez AA, Colon E, Vidal JA. Multidetector CT evaluation of calcaneal fractures. Radiographics. 2011 Jan 19;31(1):81-92.

- ↑ Maskill JD, Bohay DR, Anderson JG. Calcaneus fractures: a review article. Foot and ankle clinics. 2005 Sep 1;10(3):463-89.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Koutserimpas C, Magarakis G, Kastanis G, Kontakis G, Alpantaki K. Complications of intra-articular calcaneal fractures in adults: key points for diagnosis, prevention, and treatment. Foot & ankle specialist. 2016 Dec;9(6):534-42.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Takasaka M, Bittar CK, Mennucci FS, de Mattos CA, Zabeu JL. Comparative study on three surgical techniques for intra-articular calcaneal fractures: open reduction with internal fixation using a plate, external fixation and minimally invasive surgery. Revista Brasileira de Ortopedia (English Edition). 2016 May 1;51(3):254-60.

- ↑ Mitchell MJ, McKinley JC, Robinson CM. The epidemiology of calcaneal fractures. The Foot. 2009 Dec 1;19(4):197-200.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 Dhillon MS. Fractures of the calcaneus. JP Medical Ltd; 2013 Apr 30.

- ↑ http://www.eorif.com/AnkleFoot/CalcaneousFx.html#Anchor-Associated-44867

- ↑ Böhler L. Diagnosis, pathology, and treatment of fractures of the os calcis. JBJS. 1931 Jan 1;13(1):75-89.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Fischer, J.S.,MD; A. J. . Lowe, MD. (2016) Calcaneus (heel bone) fractures. Geraadpleegd op 5 december 2016.

- ↑ Green, D. P. (2010). Rockwood and Green's fractures in adults (Vol. 1). C. A. Rockwood, R. W. Bucholz, J. D. Heckman, & P. Tornetta (Eds.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- ↑ Huskisson EC. Measurement of pain. The lancet. 1974 Nov 9;304(7889):1127-31.

- ↑ Buckly R. Operative compared with nonoperative treatment of displaced intra-articular calcaneal fractures. J. Bone Joint Surg., A. 2002;84:1733-44.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Griffin D, Parsons N, Shaw E, Kulikov Y, Hutchinson C, Thorogood M, Lamb SE. Operative versus non-operative treatment for closed, displaced, intra-articular fractures of the calcaneus: randomised controlled trial. Bmj. 2014 Jul 24;349:g4483.

- ↑ Lance EM, CAREY EJ, WADE PA. 9 Fractures of the Os Calcis: Treatment by Early Mobilization. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research (1976-2007). 1963 Jan 1;30:76-90.

- ↑ Joe Hodges PT, Robert Klingman,"Calcaneal Fracture and Rehabilitation".

- ↑ Hu QD, Jiao PY, Shao CS, Zhang WG, Zhang K, Li Q. Manipulative reduction and external fixation with cardboard for the treatment of distal radial fracture. Zhongguo gu shang= China journal of orthopaedics and traumatology. 2011 Nov;24(11):907-9.