Adolescent Back Pain: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

= Epidemiology = | = Epidemiology = | ||

<u></u> <span style="line-height: 1.5em;">There has been a high prevalence of low back pain (LBP) in adolescents demonstrated in a number of epidemiological studies </span><ref name="Pellise et al">Pellisé F, Balagué F, Rajmil L, Cedraschi C, Aguirre M, Fontecha C et al. Prevalence of Low Back Pain and Its Effect on Health-Related Quality of Life in Adolescents. Archives of Pediatrics &amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp; Adolescent Medicine. 2009;163(1):65.</ref><span style="line-height: 1.5em;">. Estimates of the prevalence of back pain in children adolescents vary greatly, ranging from 30%-70% </span><ref name="Balague et al">Balagué F, Troussier B, Salminen J. Non-specific low back pain in children and adolescents: risk factors. European Spine Journal. 1999;8(6):429-438.</ref><ref name="Wedderkopp et al">Wedderkopp N, Leboeuf-Yde C, Andersen L, Froberg K, Hansen H. Back Pain Reporting Pattern in a Danish Population-Based Sample of Children and Adolescents. Spine. 2001;26(17):1879-1883.</ref><span style="line-height: 1.5em;">. The study by Jeffries et al (2007) found a life time prevalence ranging from 4.7% to 74.4% for spinal or back pain and 7% to 72% for LBP</span><ref name="Jeffries et al" /><span style="line-height: 1.5em;">. These ranges depend on the age of the participants and the methodological differences, in particular the definition of back pain used</span><ref name="Jones and Macfarlane" /><span style="line-height: 1.5em;">.</span><br>This level of prevalence raises concerns due to the link between LBP in adolescents and chronic LBP in adulthood<ref name="Hestbaek et al">Hestbaek L, Leboeuf-Yde C, Kyvik K, Manniche C. The Course of Low Back Pain From Adolescence to Adulthood. Spine. 2006;31(4):468-472.</ref>. A history of symptoms has been found to be the strongest predictor of future LBP<ref name="Papageorgiou et al">Papageorgiou A, Croft P, Thomas E, Ferry S, Jayson M, Silman A. Influence of previous pain experience on the episode incidence of low back pain: results from the South Manchester Back Pain Study. Pain. 1996;66(2-3):181-185.</ref> and an early onset in life linked to chronicity<ref name="Brattberg">Brattberg G. The incidence of back pain and headache among Swedish school children. Qual Life Res. 1994;3(S1):S27-S31.</ref><ref name="Harreby et al" />. It has been found that the occurrence of back pain in adolescents increases with age, in particular in the years of early teens<ref name="Jeffries et al" />. <br>Growth and development of males and females is remarkably similar up to approximately the age of 10<ref name="Brundtland et al">Brundtland G, Liestol K, Walloe L. Height and weight of school children and adolescent girls and boys in Oslo 1970. Acta Paediatrica. 1975;64(4):565-573.</ref>. Above the age of 10, as a result of puberty, the growth patterns of males and females deviate considerably<ref name="Brundtland et al" />. By at least the age of 18 or 19 years, puberty is considered to have ceased<ref name="Jeffries et al" />. With the potential influence of puberty related growth on the incidence of adolescent back pain <ref name="Feldman">Feldman D. Risk Factors for the Development of Low Back Pain in Adolescence. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2001;154(1):30-36.</ref> it is imperative that the range of pubertal ages are taken into consideration in epidemiological studies<ref name="Jeffries et al" />. | <u></u> <span style="line-height: 1.5em;">There has been a high prevalence of low back pain (LBP) in adolescents demonstrated in a number of epidemiological studies </span><ref name="Pellise et al">Pellisé F, Balagué F, Rajmil L, Cedraschi C, Aguirre M, Fontecha C et al. Prevalence of Low Back Pain and Its Effect on Health-Related Quality of Life in Adolescents. Archives of Pediatrics &amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp; Adolescent Medicine. 2009;163(1):65.</ref><span style="line-height: 1.5em;">. Estimates of the prevalence of back pain in children adolescents vary greatly, ranging from 30%-70% </span><ref name="Balague et al">Balagué F, Troussier B, Salminen J. Non-specific low back pain in children and adolescents: risk factors. European Spine Journal. 1999;8(6):429-438.</ref><ref name="Wedderkopp et al">Wedderkopp N, Leboeuf-Yde C, Andersen L, Froberg K, Hansen H. Back Pain Reporting Pattern in a Danish Population-Based Sample of Children and Adolescents. Spine. 2001;26(17):1879-1883.</ref><span style="line-height: 1.5em;">. The study by Jeffries et al (2007) found a life time prevalence ranging from 4.7% to 74.4% for spinal or back pain and 7% to 72% for LBP</span><ref name="Jeffries et al" /><span style="line-height: 1.5em;">. These ranges depend on the age of the participants and the methodological differences, in particular the definition of back pain used</span><ref name="Jones and Macfarlane" /><span style="line-height: 1.5em;">.</span><br>This level of prevalence raises concerns due to the link between LBP in adolescents and chronic LBP in adulthood<ref name="Hestbaek et al">Hestbaek L, Leboeuf-Yde C, Kyvik K, Manniche C. The Course of Low Back Pain From Adolescence to Adulthood. Spine. 2006;31(4):468-472.</ref>. A history of symptoms has been found to be the strongest predictor of future LBP<ref name="Papageorgiou et al">Papageorgiou A, Croft P, Thomas E, Ferry S, Jayson M, Silman A. Influence of previous pain experience on the episode incidence of low back pain: results from the South Manchester Back Pain Study. Pain. 1996;66(2-3):181-185.</ref> and an early onset in life linked to chronicity<ref name="Brattberg">Brattberg G. The incidence of back pain and headache among Swedish school children. Qual Life Res. 1994;3(S1):S27-S31.</ref><ref name="Harreby et al" />. It has been found that the occurrence of back pain in adolescents increases with age, in particular in the years of early teens<ref name="Jeffries et al" />. <br>Growth and development of males and females is remarkably similar up to approximately the age of 10<ref name="Brundtland et al">Brundtland G, Liestol K, Walloe L. Height and weight of school children and adolescent girls and boys in Oslo 1970. Acta Paediatrica. 1975;64(4):565-573.</ref>. Above the age of 10, as a result of puberty, the growth patterns of males and females deviate considerably<ref name="Brundtland et al" />. By at least the age of 18 or 19 years, puberty is considered to have ceased<ref name="Jeffries et al" />. With the potential influence of puberty related growth on the incidence of adolescent back pain <ref name="Feldman">Feldman D. Risk Factors for the Development of Low Back Pain in Adolescence. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2001;154(1):30-36.</ref> it is imperative that the range of pubertal ages are taken into consideration in epidemiological studies<ref name="Jeffries et al" />. | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

| Line 90: | Line 90: | ||

== <br>Disc-related pain == | == <br>Disc-related pain == | ||

<br>Disc-related pain is generally exacerbated by flexion (forward bending) and may radiate <ref>Metzl J. Adolescent Health Update. Back pain in the adolescent. A user-friendly guide. 2nd ed. 2005.</ref>. Approximately 10% of persistent back pain in adolescents is disc related<ref>Micheli L. Back Pain in Young Athletes. Archives of Pediatrics &amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp; Adolescent Medicine. 1995;149(1):15.</ref>. | <br>Disc-related pain is generally exacerbated by flexion (forward bending) and may radiate <ref>Metzl J. Adolescent Health Update. Back pain in the adolescent. A user-friendly guide. 2nd ed. 2005.</ref>. Approximately 10% of persistent back pain in adolescents is disc related<ref>Micheli L. Back Pain in Young Athletes. Archives of Pediatrics &amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp; Adolescent Medicine. 1995;149(1):15.</ref>. | ||

[http://www.physio-pedia.com/Disc_Herniation '''Disc herniation'''] | [http://www.physio-pedia.com/Disc_Herniation '''Disc herniation'''] | ||

| Line 113: | Line 113: | ||

*Back pain caused by a spinal tumour is a rare occurrence<ref>Spine-health. Potential Causes of Back Pain in Children and Teens [Internet]. 2015 [cited 14 January 2015]. Available from: http://www.spine-health.com/conditions/lower-back-pain/potential-causes-back-pain-children-and-teens</ref> | *Back pain caused by a spinal tumour is a rare occurrence<ref>Spine-health. Potential Causes of Back Pain in Children and Teens [Internet]. 2015 [cited 14 January 2015]. Available from: http://www.spine-health.com/conditions/lower-back-pain/potential-causes-back-pain-children-and-teens</ref> | ||

*The most common tumour that presents with back pain in adolescents is [http://www.physio-pedia.com/Osteoid_Osteoma O<u>steoid Osteoma</u>]<ref>Greenspan A, Jundt G, Remagen W, Greenspan A. Differential diagnosis in orthopaedic oncology. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams &amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp; Wilkins; 2007.</ref>, a benign tumour characterized by nocturnal pain and prompt relief with NSAIDs, although these features are variable. | *The most common tumour that presents with back pain in adolescents is [http://www.physio-pedia.com/Osteoid_Osteoma O<u>steoid Osteoma</u>]<ref>Greenspan A, Jundt G, Remagen W, Greenspan A. Differential diagnosis in orthopaedic oncology. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams &amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp; Wilkins; 2007.</ref>, a benign tumour characterized by nocturnal pain and prompt relief with NSAIDs, although these features are variable. | ||

*Only 10 to 20% of osteoid osteomas are localised to the spine<ref>Cohen M, Harrington T, Ginsburg W. Osteoid osteoma: 95 cases and a review of the literature. Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism. 1983;12(3):265-281.</ref><br> | *Only 10 to 20% of osteoid osteomas are localised to the spine<ref>Cohen M, Harrington T, Ginsburg W. Osteoid osteoma: 95 cases and a review of the literature. Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism. 1983;12(3):265-281.</ref><br> | ||

| Line 127: | Line 127: | ||

*<u></u> Treatment of LBP in '''adults''' has been investigated extensively<ref name="Calvo-Munoz et al">Calvo-Muñoz I, Gómez-Conesa A, Sánchez-Meca J. Physical therapy treatments for low back pain in children and adolescents: a meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2013;14(1):55.</ref>. Evidence has shown that physiotherapy treatment with exercise, back school and manual therapy are effective in reducing pain and functional limitations in adults <ref name="Heymans et al">Heymans M, van Tulder M, Esmail R, Bombardier C, Koes B. Back Schools for Nonspecific Low Back Pain. Spine. 2005;30(19):2153-2163.</ref>(Heymans et al and Aure). | *<u></u> Treatment of LBP in '''adults''' has been investigated extensively<ref name="Calvo-Munoz et al">Calvo-Muñoz I, Gómez-Conesa A, Sánchez-Meca J. Physical therapy treatments for low back pain in children and adolescents: a meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2013;14(1):55.</ref>. Evidence has shown that physiotherapy treatment with exercise, back school and manual therapy are effective in reducing pain and functional limitations in adults <ref name="Heymans et al">Heymans M, van Tulder M, Esmail R, Bombardier C, Koes B. Back Schools for Nonspecific Low Back Pain. Spine. 2005;30(19):2153-2163.</ref>(Heymans et al and Aure). | ||

*A study looking at low back pain in adolescent athletes suggested that despite undergoing pubescent changes into adulthood, adolescents cannot be treated like young adults. Therefore, treatment of adolescents can be difficult and must be approached differently, with good understanding of spinal development <ref name="De Luigi">De Luigi A. Low Back Pain in the Adolescent Athlete. Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Clinics of North America. 2014;25(4):763-788.</ref> | *A study looking at low back pain in adolescent athletes suggested that despite undergoing pubescent changes into adulthood, adolescents cannot be treated like young adults. Therefore, treatment of adolescents can be difficult and must be approached differently, with good understanding of spinal development <ref name="De Luigi">De Luigi A. Low Back Pain in the Adolescent Athlete. Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Clinics of North America. 2014;25(4):763-788.</ref>.<br> | ||

*Investigation and practice of therapeutic treatments for children and adolescents with back pain is more recent than with adults <ref name="Calvo-Munoz et al" />. Treatments used include back education, exercise, manual therapy and therapeutic conditioning. These interventions are primarily aimed at decreasing the prevalence, and lessening the intensity of LBP and disability<ref name="Calvo-Munoz et al" /> . | *Investigation and practice of therapeutic treatments for children and adolescents with back pain is more recent than with adults <ref name="Calvo-Munoz et al" />. Treatments used include back education, exercise, manual therapy and therapeutic conditioning. These interventions are primarily aimed at decreasing the prevalence, and lessening the intensity of LBP and disability<ref name="Calvo-Munoz et al" />. | ||

== <br>Prevention of LBP == | == <br>Prevention of LBP == | ||

| Line 134: | Line 134: | ||

*Preventative treatments have been carried out over the last 3 decades, including physical therapy exercises, postural hygiene and the promotion of physical activity <ref name="Calvo-Munoz et al" />. | *Preventative treatments have been carried out over the last 3 decades, including physical therapy exercises, postural hygiene and the promotion of physical activity <ref name="Calvo-Munoz et al" />. | ||

*According to Curtis and d’Hemecourt (2007) the best prevention of back pain is '''early detection'''. | *According to Curtis and d’Hemecourt (2007) the best prevention of back pain is '''early detection'''. | ||

*Preventative measures can include ‘proper technique’ e.g. in lifting sports and limiting excessive lumbar lordosis, plus participating in core-strengthening exercises and stretches for tight hamstrings and hip flexors which also may help reduce the risk of low back pain<ref name="Purcell">Purcell L, Micheli L. Low Back Pain in Young Athletes. Sports Health: A Multidisciplinary Approach. 2009;1(3):212-222.</ref> | *Preventative measures can include ‘proper technique’ e.g. in lifting sports and limiting excessive lumbar lordosis, plus participating in core-strengthening exercises and stretches for tight hamstrings and hip flexors which also may help reduce the risk of low back pain<ref name="Purcell">Purcell L, Micheli L. Low Back Pain in Young Athletes. Sports Health: A Multidisciplinary Approach. 2009;1(3):212-222.</ref>. | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

| Line 147: | Line 147: | ||

*Carry a school backpack on two shoulders | *Carry a school backpack on two shoulders | ||

*Correct the belief that school backpack weight does not affect the back | *Correct the belief that school backpack weight does not affect the back | ||

*Using a locker at school<br> | *Using a locker at school<br><ref name="Vidal et al">Effects of a postural education program on school backpack habits related to low back pain in children. Vidal J, Borràs PA, Ponseti FJ, Cantallops J, Ortega FB, Palou P. Eur Spine J. 2013 Apr;22(4):782-7. doi: 10.1007/s00586-012-2558-7. Epub 2012 Nov 10. The Spine Journal. 2013;13(12):1964.</ref> | ||

<br>The study found that children were able to learn healthy backpack habits. However, this study was in primary school aged children rather than secondary, therefore results may not be generalisable for an adolescent population. <br> | <br>The study found that children were able to learn healthy backpack habits. However, this study was in primary school aged children rather than secondary, therefore results may not be generalisable for an adolescent population. <br> | ||

| Line 163: | Line 163: | ||

*'''Manual therapy'''- mobilisation, manipulation, massage | *'''Manual therapy'''- mobilisation, manipulation, massage | ||

*'''Therapeutic physical conditioning'''- walking, running, swimming, cycling. | *'''Therapeutic physical conditioning'''- walking, running, swimming, cycling.<br><ref name="Calvo-Munoz et al" /> | ||

<br> A meta analysis in 2013 examined the differential effectiveness of physiotherapy treatment for LBP in children and adolescents aiming to determine whether the treatments were beneficial for pain and disability among other outcome variables. Prior to this analysis, there was no solid evidence to suggest which treatment was most effective for adolescents with back pain. | |||

<br> A meta analysis<ref name="Calvo-Munoz et al" /> in 2013 examined the differential effectiveness of physiotherapy treatment for LBP in children and adolescents aiming to determine whether the treatments were beneficial for pain and disability among other outcome variables. Prior to this analysis, there was no solid evidence to suggest which treatment was most effective for adolescents with back pain. | |||

<br> All the treatment outcome measures reached a statistically significant effect magnitude and showed a clinically relevant improvement of symptoms. The most effective combination treatment was therapeutic physical conditioning (ie general fitness) and manual therapy. However, there was limited details of what the treatments actually involved. | <br> All the treatment outcome measures reached a statistically significant effect magnitude and showed a clinically relevant improvement of symptoms. The most effective combination treatment was therapeutic physical conditioning (ie general fitness) and manual therapy. However, there was limited details of what the treatments actually involved. | ||

| Line 184: | Line 186: | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

According to Jones et al, 2007 and Cardon et al 2007, there is a need to incorporate back care and exercise into physical education curricula in schools.<br> | According to Jones et al, 2007 and Cardon et al 2007, there is a need to incorporate back care and exercise into physical education curricula in schools<ref name="Jones et al">Jones M, Stratton G, Reilly T, Unnithan V. Recurrent non-specific low-back pain in adolescents: the role of exercise. Ergonomics. 2007;50(10):1680-1688.</ref><ref name="Cardon et al">Cardon G, de Clercq D, Geldhof E, Verstraete S, de Bourdeaudhuij I. Back education in elementary schoolchildren: the effects of adding a physical activity promotion program to a back care program. European Spine Journal. 2006;16(1):125-133.</ref>.<br> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

Interestingly, an RCT by Ahlqwist (2008) found that an active physiotherapy program improved adolescent experience of back pain regardless of whether the program consisted of supervised exercises by a physiotherapist.<br> <u></u> <u></u> | Interestingly, an RCT by Ahlqwist (2008) found that an active physiotherapy program improved adolescent experience of back pain regardless of whether the program consisted of supervised exercises by a physiotherapist<ref name="Ahlqwist et al">Ahlqwist A, Hagman M, Kjellby-Wendt G, Beckung E. Physical Therapy Treatment of Back Complaints on Children and Adolescents. Spine. 2008;33(20):E721-E727.</ref>.<br> <u></u> <u></u> | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

Revision as of 19:25, 14 January 2015

Introduction[edit | edit source]

The World Health Organization describes adolescence as “young people between the ages of 10 and 19 years”[1]. This definition is further divided into early adolescence (10-14 years old) to late adolescence (15-19 years old) by the United Nations Population Fund [2]. Adolescent back pain has been reported to be as common as that of adult populations [3][4][5] and has been attributed to a number of factors such as gender [6], age [7], sitting for long periods [8], working at computers [9], school seating [10] and psychological factors [11].

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

There has been a high prevalence of low back pain (LBP) in adolescents demonstrated in a number of epidemiological studies [12]. Estimates of the prevalence of back pain in children adolescents vary greatly, ranging from 30%-70% [13][14]. The study by Jeffries et al (2007) found a life time prevalence ranging from 4.7% to 74.4% for spinal or back pain and 7% to 72% for LBP[7]. These ranges depend on the age of the participants and the methodological differences, in particular the definition of back pain used[3].

This level of prevalence raises concerns due to the link between LBP in adolescents and chronic LBP in adulthood[15]. A history of symptoms has been found to be the strongest predictor of future LBP[16] and an early onset in life linked to chronicity[17][5]. It has been found that the occurrence of back pain in adolescents increases with age, in particular in the years of early teens[7].

Growth and development of males and females is remarkably similar up to approximately the age of 10[18]. Above the age of 10, as a result of puberty, the growth patterns of males and females deviate considerably[18]. By at least the age of 18 or 19 years, puberty is considered to have ceased[7]. With the potential influence of puberty related growth on the incidence of adolescent back pain [19] it is imperative that the range of pubertal ages are taken into consideration in epidemiological studies[7].

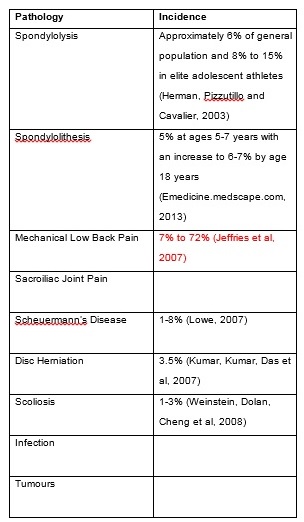

Aetiology[edit | edit source]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Adolescent back pain predominantly falls into 3 general categories: muscular, bone-related, and discogenic [20].

Each with characteristic features as displayed in this section:

[edit | edit source]

Most back pain in adolescents, as in adults, is thought to arise from within the muscles [21]. Muscle-related pain tends to be localised to paraspinal muscles of the thoracic or lumbar area rather than to the spine itself [22]

This pain is most commonly related to overuse, but there may be a history of acute injury.

The contributing factors may include:

- Carrying a heavy rucksack[23] [24]

- Incorrect sports equipment (e.g. improper bicycle seat positioning, lack of cushioned insoles for running) [25]

- Psychosocial distress, depression and anxiety[26][27]

[edit | edit source]

Bone-related pain tends to occur at the centre of the spine and usually exacerbated by extension (backward bending) [28], though this finding is not specific.

Common causes of bone related back pain amongst adolescents include:

- Spondylolysis is a unilateral/bilateral defect (separation) in the vertebral pars interarticularis (usually the lower lumbar vertebrae - particularly L5) (Morita et al., 1995).

- Spondylolysis usually presents in early adolescence. It may be asymptomatic initially, but typically manifests as aching low back pain exacerbated by hyperextension of the spine and relieved by rest[29].

- Spondylolysis is common in adolescent athletes with acute low back pain - accounting for 47% of cases in one orthopaedic series (Micheli and Wood, 1995). The risk of developing Spondylolysis tends to correlate in athletes whose sport requires repetitive flexion/extension or hyperextension (Baker and Patel, 2005)

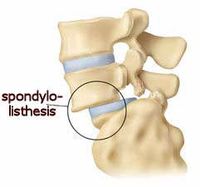

- Occurs when bilateral pars defects permit the vertebral body to slip anteriorly - the most common spondylolytic defects occur at the isthmus (Ginsburg and Bassett, 1997)

- Spondylolysis progresses to spondylolisthesis in approximately 15 % of cases.[30]Progression generally occurs during the teenage growth spurt, with minimal change after 16 years [31][32]. Morita et al (1995) suggests progression to spondylolisthesis is correlated with chronicity of pain.

VIDEO ANIMATION - Click here [X] (Select Spondylolithesis)

Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis

Scoliosis

- Scoliosis is an abnormal lateral curvature of the spine. It can be idiopathic or result from congenital spinal anomalies, muscular spasm or paralysis, infection, tumour, or other causes (REFERENCE)

Idiopathic scoliosis

- Scoliosis for which there is no definite aetiology.

Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS)

- AIS is the most common form of idiopathic scoliosis, accounting for 80 to 85% of cases[33]

- AIS is also noted as the most common spinal deformity seen by primary care physicians, paediatricians, and spinal surgeons[34].

- The prevalence of adolescents with a Cobb angle (curvature) ≥10º is approximately 3 %.

- Only 10% of individuals with AIS require treatment.

- Males : Females = 1:1. Though, the risk of curve progression and therefore the need for later treatment is 10 x higher in females [35].

Scheuermann’s Disease / Juvenile Kyphosis

- Sheuermann's Disease is the abnormal growth (osteochondrosis), typically of the thoracolumbar spine leading to increasing spinal curvature (Cassas and Cassettari-Wayhs, 2006)

- It may be associated with spondylosis[36]

- Scheuermann’s is the most common cause of structural kyphosis in adolescents[37]and often accompanied with poor posture and backache (http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/311959-overview)

[edit | edit source]

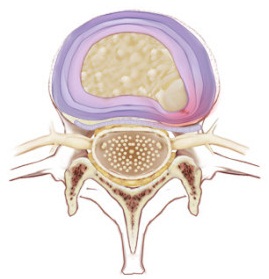

Disc-related pain is generally exacerbated by flexion (forward bending) and may radiate [38]. Approximately 10% of persistent back pain in adolescents is disc related[39].

Vertebral bodies are separated by intervertebral discs, (to provide support and mobility). The intervertebral disc is composed of a tough, ligamentous outer annulus and a gelatinous inner nucleus pulposus. The combination of intervertebral pressure and degeneration of the ligamentous fibres can lead to a tear in the annulus, allowing herniation of the nucleus pulposus.

- Disc herniation is a common disorder among adults with degenerated intervertebral discs. However, its occurrence in adolescence is much less frequent mostly as adolescents tend to have a healthier lumbar spine[40]. Herniation of the nucleus pulposus is much less common in children and adolescents than in adults[41]

Risk factors for disc herniation include[13][42]:

- Acute trauma

- Scheuermann’s disease

- Family history of disc herniation

- Obesity

- Sporting activities e.g. weight lifting, wrestling, gymnastics, and collision sports

Other possible causes of back pain:[edit | edit source]

Tumour

- Back pain caused by a spinal tumour is a rare occurrence[43]

- The most common tumour that presents with back pain in adolescents is Osteoid Osteoma[44], a benign tumour characterized by nocturnal pain and prompt relief with NSAIDs, although these features are variable.

- Only 10 to 20% of osteoid osteomas are localised to the spine[45]

Infection

Physiotherapy Treatment[edit | edit source]

Overview[edit | edit source]

- Treatment of LBP in adults has been investigated extensively[46]. Evidence has shown that physiotherapy treatment with exercise, back school and manual therapy are effective in reducing pain and functional limitations in adults [47](Heymans et al and Aure).

- A study looking at low back pain in adolescent athletes suggested that despite undergoing pubescent changes into adulthood, adolescents cannot be treated like young adults. Therefore, treatment of adolescents can be difficult and must be approached differently, with good understanding of spinal development [48].

- Investigation and practice of therapeutic treatments for children and adolescents with back pain is more recent than with adults [46]. Treatments used include back education, exercise, manual therapy and therapeutic conditioning. These interventions are primarily aimed at decreasing the prevalence, and lessening the intensity of LBP and disability[46].

Prevention of LBP[edit | edit source]

- Preventative treatments have been carried out over the last 3 decades, including physical therapy exercises, postural hygiene and the promotion of physical activity [46].

- According to Curtis and d’Hemecourt (2007) the best prevention of back pain is early detection.

- Preventative measures can include ‘proper technique’ e.g. in lifting sports and limiting excessive lumbar lordosis, plus participating in core-strengthening exercises and stretches for tight hamstrings and hip flexors which also may help reduce the risk of low back pain[49].

School backpacks and LBP[edit | edit source]

Some literature suggests that back packs carried by schoolchildren can cause back pain if they are to heavy or if the weight is carried unevenly. (?NHSCHOICES)

According to this group-randomised control trial the following should be advised to prevent LBP:

- Load the minimum weight possible

- Carry a school backpack on two shoulders

- Correct the belief that school backpack weight does not affect the back

- Using a locker at school

[50]

The study found that children were able to learn healthy backpack habits. However, this study was in primary school aged children rather than secondary, therefore results may not be generalisable for an adolescent population.

Treatment[edit | edit source]

It has been concluded that physiotherapy treatments seem to be effective in adolescents with LBP [46].

Suggested treatments for the rehabilitation of adolescents with back pain include:

- Back education (theoretical or practical)- acquisition of knowledge, posture training habits, body awareness training

- Exercise- including stretching, strengthening, breathing, posture correction, balance exercises, functional exercises, warm-up, relaxation, coordination, stabilisation.

A study which evaluated the efficacy of an exercise program for recurrent non-specific back pain in adolescents, concluding that an exercise was an effective short-term treatment strategy, incorporated the following forms of exercise:

a) Pain relieving exercises which encourage motion of the lumbar spine to reduce joint stiffness such as the ‘cat stretch’ and flexibility exercises for the hip and knee, such as knees to chest and knees to the side

b)Reconditioning exercises aiming to provide muscle endurance of lumbar stabilisers and help encourage appropriate motor control of muscle recruitment such as ‘superman’ single leg extension holds in ?4 point kneeling.

c) Progressive exercises imposing a higher challenge on the lumbar stabilisers and more strength related activities, for instance horizontal side support on feet.

- Manual therapy- mobilisation, manipulation, massage

- Therapeutic physical conditioning- walking, running, swimming, cycling.

[46]

A meta analysis[46] in 2013 examined the differential effectiveness of physiotherapy treatment for LBP in children and adolescents aiming to determine whether the treatments were beneficial for pain and disability among other outcome variables. Prior to this analysis, there was no solid evidence to suggest which treatment was most effective for adolescents with back pain.

All the treatment outcome measures reached a statistically significant effect magnitude and showed a clinically relevant improvement of symptoms. The most effective combination treatment was therapeutic physical conditioning (ie general fitness) and manual therapy. However, there was limited details of what the treatments actually involved.

Intensity and duration of treatment[edit | edit source]

The study found that the average:

- number of weeks of treatment was 12

- time a week spent engaging in treatment was 1 hour

Quality of the study

[edit | edit source]

The meta-analysis itself has good methodological quality, however, there was a low number of applicable studies with only 8 articles met the selection criteria. There was also a lack of control groups and methodological quality of the studies was poor. This prevents definite conclusions being drawn. Furthermore, no evidence was provided regarding the duration of the beneficial effects, or details of follow up.

According to Jones et al, 2007 and Cardon et al 2007, there is a need to incorporate back care and exercise into physical education curricula in schools[51][52].

Interestingly, an RCT by Ahlqwist (2008) found that an active physiotherapy program improved adolescent experience of back pain regardless of whether the program consisted of supervised exercises by a physiotherapist[53].

Conclusion[edit | edit source]

Outcome measures

[edit | edit source]

There are many different outcome measures that may be used by physiotherapists in their treatment of adolescents with back pain.

- Pain e.g. VAS, Painometer (a smartphone app to assess pain intensity)

- Disability e.g. Modified Oswestry Disability Questionnaire, Roland & Morris Disability Questionnaire

- Flexibility eg Back-saver sit and reach

- Endurance

- Mental health

- Quality of life e.g. Child Health Questionnaire Child Form 87

- Function

- Self efficacy

- Return to sport

- Return to study/work

Further research[edit | edit source]

References

- ↑ Who.int. WHO | Adolescent health [Internet]. 2015 [cited 9 January 2015]. Available from: http://www.who.int/topics/adolescent_health/en/

- ↑ Unfpa.org. UNFPA - United Nations Population Fund | State of World Population 2003 [Internet]. 2003 [cited 12 January 2015]. Available from: http://www.unfpa.org/publications/state-world-population-2003

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Jones G, Macfarlane G. Epidemiology of low back pain in children and adolescents. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 2005;90(3):312-316.

- ↑ Burton A, Clarke R, McClune T, Tillotson K. The Natural History of Low Back Pain in Adolescents. Spine. 1996;21(20):2323-2328.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Harreby M, Neergaard K, Hesselsôe G, Kjer J. Are Radiologic Changes in the Thoracic and Lumbar Spine of Adolescents Risk Factors for Low Back Pain in Adults?. Spine. 1995;20(21):2298-2302.

- ↑ Grimmer K, Nyland L, Milanese S. Longitudinal investigation of low back pain in Australian adolescents: a five-year study. Physiother Res Int. 2006;11(3):161-172.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 Jeffries L, Milanese S, Grimmer-Somers K. Epidemiology of Adolescent Spinal Pain. Spine. 2007;32(23):2630-2637.

- ↑ Grimmer K, Williams M. Gender-age environmental associates of adolescent low back pain. Applied Ergonomics. 2000;31(4):343-360.

- ↑ Hakala P, Rimpela A, Saarni L, Salminen J. Frequent computer-related activities increase the risk of neck-shoulder and low back pain in adolescents. The European Journal of Public Health. 2005;16(5):536-541.

- ↑ Troussiere B, Tesniere C, Fauconnier J, Grison J, Juvin R, Phelip X. Comparative study of two different kinds of school furniture among children. Ergonomics. 1999;42(3):516-526.

- ↑ Astfalck R, O'Sullivan P, Straker L, Smith A. A detailed characterisation of pain, disability, physical and psychological features of a small group of adolescents with non-specific chronic low back pain. Manual Therapy. 2010;15(3):240-247.

- ↑ Pellisé F, Balagué F, Rajmil L, Cedraschi C, Aguirre M, Fontecha C et al. Prevalence of Low Back Pain and Its Effect on Health-Related Quality of Life in Adolescents. Archives of Pediatrics &amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp; Adolescent Medicine. 2009;163(1):65.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Balagué F, Troussier B, Salminen J. Non-specific low back pain in children and adolescents: risk factors. European Spine Journal. 1999;8(6):429-438.

- ↑ Wedderkopp N, Leboeuf-Yde C, Andersen L, Froberg K, Hansen H. Back Pain Reporting Pattern in a Danish Population-Based Sample of Children and Adolescents. Spine. 2001;26(17):1879-1883.

- ↑ Hestbaek L, Leboeuf-Yde C, Kyvik K, Manniche C. The Course of Low Back Pain From Adolescence to Adulthood. Spine. 2006;31(4):468-472.

- ↑ Papageorgiou A, Croft P, Thomas E, Ferry S, Jayson M, Silman A. Influence of previous pain experience on the episode incidence of low back pain: results from the South Manchester Back Pain Study. Pain. 1996;66(2-3):181-185.

- ↑ Brattberg G. The incidence of back pain and headache among Swedish school children. Qual Life Res. 1994;3(S1):S27-S31.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Brundtland G, Liestol K, Walloe L. Height and weight of school children and adolescent girls and boys in Oslo 1970. Acta Paediatrica. 1975;64(4):565-573.

- ↑ Feldman D. Risk Factors for the Development of Low Back Pain in Adolescence. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2001;154(1):30-36.

- ↑ Metzl J. Adolescent Health Update. Back pain in the adolescent. A user-friendly guide. 2nd ed. 2005.

- ↑ Kim H, Green D. Adolescent back pain. Current Opinion in Pediatrics. 2008;20(1):37-45.

- ↑ Metzl J. Adolescent Health Update. Back pain in the adolescent. A user-friendly guide. 2nd ed. 2005.

- ↑ Macias B, Murthy G, Chambers H, Hargens A. Asymmetric Loads and Pain Associated With Backpack Carrying by Children. Journal of Pediatric Orthopaedics. 2008;28(5):512-517.

- ↑ Rodriguez-Oviedo P, Ruano-Ravina A, Perez-Rios M, Garcia F, Gomez-Fernandez D, Fernandez-Alonso A et al. School children's backpacks, back pain and back pathologies. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 2012;97(8):730-732.

- ↑ Baker R, Patel D. Lower Back Pain in the Athlete: Common Conditions and Treatment. Primary Care: Clinics in Office Practice. 2005;32(1):201-229.

- ↑ COMBS J, CASKEY P. Back Pain in Children and Adolescents. Southern Medical Journal. 1997;90(8):789-792.

- ↑ Diepenmaat A. Neck/Shoulder, Low Back, and Arm Pain in Relation to Computer Use, Physical Activity, Stress, and Depression Among Dutch Adolescents. PEDIATRICS. 2006;117(2):412-416.

- ↑ Metzl J. Adolescent Health Update. Back pain in the adolescent. A user-friendly guide. 2nd ed. 2005.

- ↑ Kim H, Green D. Adolescent back pain. Current Opinion in Pediatrics. 2008;20(1):37-45.

- ↑ eutler W, Fredrickson B, Murtland A, Sweeney C, Grant W, Baker D. The Natural History of Spondylolysis and Spondylolisthesis. Spine. 2003;28(10):1027-1035.

- ↑ Lonstein J. Spondylolisthesis in Children. Spine. 1999;24(24):2640.

- ↑ Motley G, Nyland J, Jacobs J, Caborn D. The Pars Interarticularis Stress Reaction, Spondylolysis, and Spondylolisthesis Progression. Journal of Athletic Training. 1998;33:351-358.

- ↑ 0. Negrini S, Aulisa A, Aulisa L, Circo A, de Mauroy J, Durmala J et al. 2011 SOSORT guidelines: Orthopaedic and Rehabilitation treatment of idiopathic scoliosis during growth. Scoliosis. 2012;7(1):3.

- ↑ 11. Altaf F, Gibson A, Dannawi Z, Noordeen H. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. BMJ. 2013;346(apr30 1):f2508-f2508.

- ↑ Miller N. CAUSE AND NATURAL HISTORY OF ADOLESCENT IDIOPATHIC SCOLIOSIS. Orthopedic Clinics of North America. 1999;30(3):343-352.

- ↑ 13. OGILVIE J, SHERMAN J. Spondylolysis in Scheuermannʼs Disease. Spine. 1987;12(3):251-253.

- ↑ Lowe T. Scheuermann's Kyphosis. Neurosurgery Clinics of North America. 2007;18(2):305-315.

- ↑ Metzl J. Adolescent Health Update. Back pain in the adolescent. A user-friendly guide. 2nd ed. 2005.

- ↑ Micheli L. Back Pain in Young Athletes. Archives of Pediatrics &amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp; Adolescent Medicine. 1995;149(1):15.

- ↑ Dang L, Liu Z. A review of current treatment for lumbar disc herniation in children and adolescents. European Spine Journal. 2009;19(2):205-214.

- ↑ 18. Haidar R, Ghanem I, Saad S, Uthman I. Lumbar disc herniation in young children. Acta Paediatrica. 2009;.

- ↑ DePalma M, Bhargava A. Nonspondylolytic Etiologies of Lumbar Pain in the Young Athlete. Current Sports Medicine Reports. 2006;5(1):44-49.

- ↑ Spine-health. Potential Causes of Back Pain in Children and Teens [Internet]. 2015 [cited 14 January 2015]. Available from: http://www.spine-health.com/conditions/lower-back-pain/potential-causes-back-pain-children-and-teens

- ↑ Greenspan A, Jundt G, Remagen W, Greenspan A. Differential diagnosis in orthopaedic oncology. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams &amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp; Wilkins; 2007.

- ↑ Cohen M, Harrington T, Ginsburg W. Osteoid osteoma: 95 cases and a review of the literature. Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism. 1983;12(3):265-281.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 46.2 46.3 46.4 46.5 46.6 Calvo-Muñoz I, Gómez-Conesa A, Sánchez-Meca J. Physical therapy treatments for low back pain in children and adolescents: a meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2013;14(1):55.

- ↑ Heymans M, van Tulder M, Esmail R, Bombardier C, Koes B. Back Schools for Nonspecific Low Back Pain. Spine. 2005;30(19):2153-2163.

- ↑ De Luigi A. Low Back Pain in the Adolescent Athlete. Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Clinics of North America. 2014;25(4):763-788.

- ↑ Purcell L, Micheli L. Low Back Pain in Young Athletes. Sports Health: A Multidisciplinary Approach. 2009;1(3):212-222.

- ↑ Effects of a postural education program on school backpack habits related to low back pain in children. Vidal J, Borràs PA, Ponseti FJ, Cantallops J, Ortega FB, Palou P. Eur Spine J. 2013 Apr;22(4):782-7. doi: 10.1007/s00586-012-2558-7. Epub 2012 Nov 10. The Spine Journal. 2013;13(12):1964.

- ↑ Jones M, Stratton G, Reilly T, Unnithan V. Recurrent non-specific low-back pain in adolescents: the role of exercise. Ergonomics. 2007;50(10):1680-1688.

- ↑ Cardon G, de Clercq D, Geldhof E, Verstraete S, de Bourdeaudhuij I. Back education in elementary schoolchildren: the effects of adding a physical activity promotion program to a back care program. European Spine Journal. 2006;16(1):125-133.

- ↑ Ahlqwist A, Hagman M, Kjellby-Wendt G, Beckung E. Physical Therapy Treatment of Back Complaints on Children and Adolescents. Spine. 2008;33(20):E721-E727.