Abdominal Muscles

Original Editor - Anne Millar

Top Contributors - Anne Millar, Khloud Shreif, Lucinda hampton, Laura Ritchie, Kim Jackson, Admin, Joao Costa, Scott Buxton, Vidhu Sindwani and Evan Thomas

Introduction[edit | edit source]

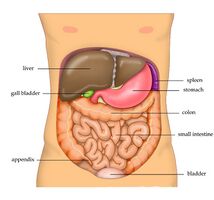

The abdominal muscles are the muscles forming the abdominal walls, the abdomen being the portion of the trunk connecting the thorax and pelvis. An abdominal wall is formed of skin, fascia, and muscle and encases the abdominal cavity and viscera[1].

The abdominal muscles support the trunk, allow movement, hold organs in place, and are distensible (being able accommodate dynamic changes in the volume of abdominal contents)[1].

The deep abdominal muscles, together with the intrinsic back muscles, make up the core muscles and help keep the body stable and balanced, and protects the spine.

Causes of abdominal muscle strains include overstretching, overuse or a violent, poorly performed movement of the trunk[2].

Anatomy[edit | edit source]

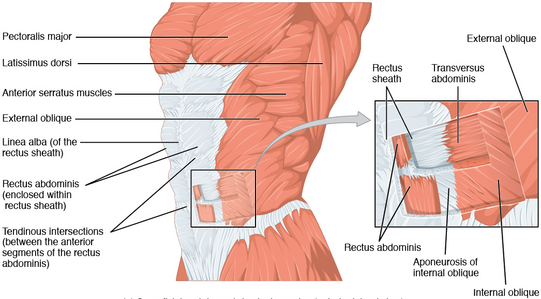

When people think of abdominal muscles it is these four main muscles

- Transversus abdominis – the deepest muscle layer. Its main roles are to stabilise the trunk and maintain internal abdominal pressure

- Rectus abdominis – slung between the ribs and the pubic bone at the front of the pelvis. When contracting, this muscle has the characteristic bumps or bulges that are commonly called ‘the six pack’. The main function of the rectus abdominis is to move the body between the ribcage and the pelvis

- External oblique muscles – these are on each side of the rectus abdominis. The external oblique muscles allow the trunk to twist, but to the opposite side of whichever external oblique is contracting. For example, the right external oblique contracts to turn the body to the left

- Internal oblique muscles – these flank the rectus abdominis and are located just inside the hipbones. They operate in the opposite way to the external oblique muscles. For example, twisting the trunk to the left requires the left side internal oblique and the right side external oblique to contract together.

Structure and Function[edit | edit source]

The abdominal muscles however are more extensive and may be divided broadly into: Anterolateral; and Posterior components.

Anterolateral Abdominal Wall Muscles: consists of

- 2 vertical muscles located on the midline and bisected by linea alba Rectus abdominis and pyramidalis

- 3 flat muscles on the anterolateral side arranged from superficial to deep; external abdominal oblique, internal abdominal oblique, transversus abdominis.[3]

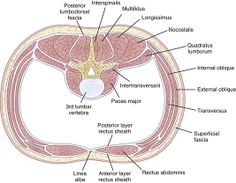

Posterior Wall Muscles

- Quadratus, quadrate shape on the lateral side of the posterior abdominal wall. originate from the ilium directed superior medially to insert into transverse process of L1-L4 and lower border of 12th rib. One of the functions of QL is lateral flexion and extension of the vertebral column and during the inhalation assist with the diaphragm and fixes the 12th rib.

- Psoas major, located lateral to the lumbar vertebrae, originate from the transverse process of T12-L5 directed inferolateral and insert into the lesser trochanter. It flexes the thigh at the hip.

- Psoas minor, doesn't present in all populations and originates from Tthe 12-L1 transverse process and inserts into pubic pectineal line.

- Iliacus, originates from the iliac fossa, and with psoas major they form iliopsoas muscle that is the main flexor of the hip.

- Diaphragm, the posterior aspect of the diaphragm.

Muscle Actions Explained[edit | edit source]

From all we mentioned before we can see that all abdominal muscles have different muscle fibers orientation and act in all three planes during movements. are linked together even by having a common site of connection or by lying fascia. When contracting one muscle other muscles will contract. For example when you aim to contract TrA at the beginning of contraction you will involve it then if you will continue or contract stronger IO will be involved then EO if you will keep going the rectus abdominis will be involved in the function.

Our body is designed to move, they work together to control the movement of the spine, pelvis, and rib cage, during gait there is relatively a counter-rotation between the upper and lower part and the arm and leg are moving in opposite direction to each other.

During normal gait, there is a time when rectus abdominis and external obliques at one side act eccentrically to decelerate the anterior pelvis tilting created by the extension of the hip of that side and RA and external obliques of the other side work eccentrically to control thoracic extension and rotation created by the extension of the shoulder.

"To describe the function of abdominal muscle it can be easily demonstrated from the supine position and flex the spine as this movement is controlled by the brain but this isn't how they actually work" stated Dr, Gray a physical therapist[6]. During mid-range of spine flexion, RA and external obliques shorten and the transversus abdominis lengthen and work together and internal obliques generate maximum of its force[7].

During the exercise program, we need to involve muscles in functional exercise for better outcome[8].

Clinical Relevance[edit | edit source]

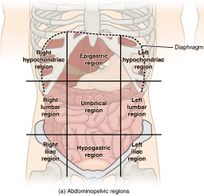

The abdominal viscera can be palpated through the abdominal wall and their place can be visually marked, the umbilicus is the most marked it is fond usually midway between the xiphoid and symphysis pubis. The linea alba splits the rectus abdominis into two half and extends from a vertical groove that presented from xiphoid process.

The abdomen is divided into 9 regions by two horizontal and two vertical plans, these regions are with benefit to describe the location of pain, identify the visceral organs, and in surgical procedures Fig2.

Transverse abdomimis as a deep abdominal muscle and one of the main important core muscle that contributes to supporting lumbopelvic stability and deficit in its function affects our back causing low back pain (LBP). We need to include it in our rehabilitation program[10]

As we mentioned before the abdominal muscles together participate to maintain your erect posture and prevent hyperlordosis pf vertebral column, hence the abdominal muscles have are flexors at the of the vertebral column. Weakness of lumbar extensors with insufficient abdominal muscle contraction in a way that can not oppose the lordosis participate in developing the hyperlordosis.

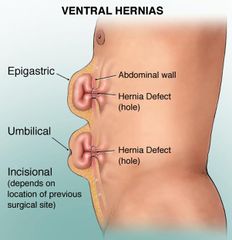

Deficit in the abdominal wall muscles congenital from birth or acquired postoperatively as a result of a poor wound healing, wound infection, or acquired weakness after pregnancy and labor for example. can manifest in the form of hernia congenital or acquired.

Congenital hernia happens during infant development as a result of embryological malformations or weakness in the neonatal abdominal wall, it may be fatal in some cases and need urgent and surgical intervention as; gastroschisis, or resolve without need to surgical intervention as in umbilical hernia.

Acquired hernia happens in the area of weakness and varies in its severity[11]:

Umbilical hernia that is more serious and has a higher rate of morbidity in adult more than infants and may need surgical intervention. Inguinal hernia protrudes at the inferior border of anterolateral muscles. Epigastric hernia, above the umbilicus through the midline of the linea alba. Spigelian hernias, and incisional hernia as a result of postoperative incision.

Rectus diastasis happens due to prolong transverse stress on linea alba during pregnancy, or post-menopausal women.

Psoas sign, that indicates there is irritation to the iliopsoas muscle group and you can test it by passive flexion of thigh if there is pain in the lower abdomen the test is positive when it is presented on the right side may be an indication of appendicitis.[12]

Physical Therapy Intervention[edit | edit source]

Abdominal exercises need to be gradually progressed from how to activate muscles and maintain contraction to integrate them with functional movement, but there's special considerations, precaution, and exercise modification that we will take these exercises for a patient with a hernia.

- Abdominal draw in exercise, easy to apply, target mainly transversus abdominis as well as the diaphragm it's an important respiratory exercise[13]. Exercise can be progressed by adding external resistance, upper limb or lower limb movement while holding abdomen drawing in. Patients with lumbar hyperlordosis draw-in exercise from borne hip extension increase the activity of gluteus maximus, weakness GM speed up lumbar hyperhidrosis, and increase the load on lumbar spine and pelvis so this exercise will be with benefit[14].

- Curl up exercise, target rectus abdominis, transverse abdominis, and obliques in addition to hip flexors, chest, and neck, start the exercise with slow movement, few repetitions and make sure the back is in contact with the floor and eccentric curl up is most effective at angle at 30∘.[15]

- Bridging, modified bridging with hip abduction or unstable surface show to increase core stability, trunk control. The activation of internal abdominis, rectus abdominis along with erector spine is greater in modified bridging when compared to standard bridging[17].

- William protocol of spine flexion has a positive effect on lumbar hyperhidrosis, back pain, increased flexibility of hip flexor and back extensions, abdominal muscle strength, and hamstring flexibility, examples of William exercises[19]:

- Pelvic tilt, from flat position and knees in flexion try to flatten your back without pushing down with your leg

- Single and double knee to chest

- Partial sit-up, with maintaining the pelvic tilt curl your head and shoulder off.

- Hamstring stretch

- Hip flexor stretch and squat.

- Plank and pilates exercises activate and strengthen core muscles along with abdominal muscles.

For more exercise descriptions see Core stability and Lumbar motor control training

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Flynn W, Vickerton P. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Abdominal Wall. Available:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK551649/ (accessed 11.2.2022)

- ↑ Better health Abdominal muscles Available: https://www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au/health/conditionsandtreatments/abdominal-muscles(accessed 12.2.2022)

- ↑ Flament JB. Functional anatomy of the abdominal wall. Der Chirurg; Zeitschrift fur alle Gebiete der operativen Medizen. 2006 May;77(5):401-7.

- ↑ Anatomy Zone. Muscles of the Anterior Abdominal Wall-3D Anatomy Tutorial. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mvOajxO8mXO [last accessed 11/07/15]

- ↑ Anatomy Zone. Muscles of the Posterior Abdominal Wall - 3D Anatomy Tutorial. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ovQYBAiv8cI[last accessed 17/5/2020]

- ↑ ACE, Functional anatomy of abdominal muscles

- ↑ clinical gait, anatomy, and biomechanics of abdominal wall muscle.

- ↑ McGill S. Core training: Evidence translating to better performance and injury prevention. Strength & Conditioning Journal. 2010 Jun 1;32(3):33-46.

- ↑ tendosport. How Abdominal Muscles Work. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4MeLHSjESlU[last accessed 20/5/2020]

- ↑ Selkow NM, Eck MR, Rivas S. Transversus abdominis activation and timing improves following core stability training: a randomized trial. International journal of sports physical therapy. 2017 Dec;12(7):1048.

- ↑ Flynn W, Vickerton P. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Abdominal Wall. InStatPearls [Internet] 2019 Dec 9. StatPearls Publishing.

- ↑ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Psoas_sign

- ↑ Oh YJ, Park SH, Lee MM. Comparison of Effects of Abdominal Draw-In Lumbar Stabilization Exercises with and without Respiratory Resistance on Women with Low Back Pain: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Medical Science Monitor: International Medical Journal of Experimental and Clinical Research. 2020;26:e921295-1.

- ↑ Kim TW, Kim YW. Effects of abdominal drawing-in during prone hip extension on the muscle activities of the hamstring, gluteus maximus, and lumbar erector spinae in subjects with lumbar hyperlordosis. Journal of physical therapy science. 2015;27(2):383-6.

- ↑ Ha SY, Shin DC. The effects of curl-up exercise in terms of posture and muscle contraction direction on muscle activity and thickness of trunk muscles. Journal of Back and Musculoskeletal Rehabilitation. 2020 Feb 28(Preprint):1-7.

- ↑ Health e-University. How to do a Curl Up: Health e-University. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lsWQ0XpiNkE[last accessed 25/4/2020

- ↑ Yoon JO, Kang MH, Kim JS, Oh JS. Effect of modified bridge exercise on trunk muscle activity in healthy adults: a cross sectional study. Brazilian journal of physical therapy. 2018 Mar 1;22(2):161-7.

- ↑ Physio Fitness | Physio REHAB | Tim Keeley. Glute Bridges and back pain - Don't flex the spine! | Feat. Tim Keeley | No.70 Physio REHAB. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SwyDMwpcW38[last accessed 25/4/2020

- ↑ Fatemi R, Javid M, Najafabadi EM. Effects of William training on lumbosacral muscles function, lumbar curve and pain. Journal of back and musculoskeletal rehabilitation. 2015 Jan 1;28(3):591-7.

- ↑ Ccedseminars. Williams Flexion Exercises for Lumbar Spine. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=757ucsakxoc[last accessed 21/5/2020]