Behavioural Approaches to Pain Management: Difference between revisions

Elvira Muhic (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

m (Edited the text for flow and reduce number of direct quotes from the references. Added references where indicated. Removed repetitive text.) |

||

| (32 intermediate revisions by 8 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

<div class="editorbox"> | |||

'''Original Editor ''' - [[User:Elvira Muhic|Elvira Muhic]] | |||

'''Original Editor ''' - | |||

'''Top Contributors''' - {{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}} | '''Top Contributors''' - {{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}} | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

== Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) | == Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) == | ||

[[Image:CBT tenets.jpg|right|300px]] | |||

Whether assessing or treating acute or [[Chronic Pain|chronic pain]] syndromes, pain management should include a [[Biopsychosocial Model|biopsychosocial approach]]. Assessment may include a focused joint and functional examination including more global areas of impairment (i.e. [[gait]], [[balance]], and endurance) and disability.<ref name="p2">Steven P. Stanos, James McLean, Lynn Rader. Physical Medicine Rehabilitation Approach to Pain. Medical Clinics of North America, Volume 91, Issue 1, Pages 57-95. 2007</ref> | |||

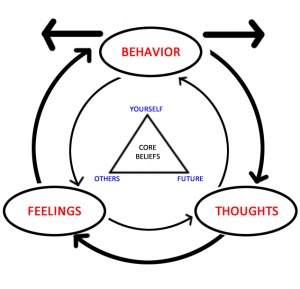

[[Cognitive Behavioural Therapy|''Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT)'']] can be described as the "gold standard" psychological treatment for individuals with a wide range of pain problems. It can be used alone or in conjunction with medical or interdisciplinary rehabilitation treatments.<ref name="p1" /> | |||

Chronic pain stands-out as the most common condition treated with CBT. The reason for this, as the Institute of Medicine<ref>Institute of Medicine. [https://www.awmf.org/fileadmin/user_upload/Leitlinien/International/IOM_CPG_lang_2011.pdf Clinical practice guidelines we can trust]. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2011. Accessed 30 August 2019.</ref> explains, is because chronic pain is a condition influenced by biological, psychological, and social factors and is optimally managed by treatments that address not only its biological causes but also its psychological and social influences and consequences.<ref name="p1">Dawn M. Ehde, Tiara M. Dillworth, and Judith A. Turner. Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Individuals With Chronic Pain - Efficacy, Innovations, and Directions for Research. University of Washington. February-March 2014</ref> Since the introduction of the biopsychosocial model, treatment for chronic pain has become multi-modal and multidisciplinary, with emphasis on a range of strategies aimed at maximising pain reduction, improving health-related quality of life, independence and mobility, enhancing psychological well-being and preventing secondary dysfunction.<ref name="p3" /> | |||

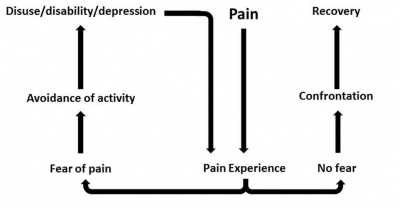

< | As time goes by, a patient with pain can develop behaviours, such as ''pain catastrophising'' (magnification of the threat of, rumination about, and perceived inability to cope with pain), as well as ''fear-avoidance'' (activity avoidance due to fear of increased pain or bodily harm), which have consistently been found to be associated with greater physical and psychosocial dysfunction, even after controlling for pain and depression levels.<ref>Edwards RR, Cahalan C, Mensing G, Smith M, Haythornthwaite JA. Pain, catastrophizing, and depression in the rheumatic diseases. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2011 Apr;7(4):216-24.</ref><ref>Phillip J Quartana, PhD, Claudia M Campbell, PhD, and Robert R Edwards. [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2696024/ Pain catastrophizing: a critical review]. Expert Rev Neurother. 2009. 9;5: 745–758. Accessed 30 August 2019.</ref><ref>Gatchel RJ, Peng YB, Peters ML, Fuchs PN, Turk DC. The biopsychosocial approach to chronic pain: scientific advances and future directions. Psychol Bull. 2007 Jul;133(4):581-624.</ref><ref>Leeuw M, Goossens M, Linton S, Crombez G, Boersma K, Vlaeyen J. [https://www.researchgate.net/publication/6618918_The_Fear-Avoidance_Model_of_Musculoskeletal_Pain_Current_State_of_Scientific_Evidence The Fear-Avoidance Model of Musculoskeletal Pain: Current State of Scientific Evidence.] Journal of behavioral medicine. 2007 30. 77-94. Accessed 30 August 2019.</ref> Individuals experiencing chronic pain may have mood, anxiety, and sleep disorders, and CBT can also be used to treat these conditions.<ref name="p1" /> | ||

=== CBT in | === CBT in Practice === | ||

There is no standard protocol for | There is no standard protocol for CBT; it varies in the number of sessions and specific techniques used. CBT for pain often includes relaxation training, setting and working toward behavioral goals such as increases in exercise and other activities, behavioural activation, guidance in activity pacing, problem-solving training, and cognitive restructuring.<ref name="p1" /> | ||

Currently, CBT is the prevailing psychological treatment for individuals with chronic pain conditions such as low back pain, headaches, arthritis, orofacial pain, and fibromyalgia. CBT has also been applied to pain associated with cancer and its treatment.<ref name=" | Currently, CBT is the prevailing psychological treatment for individuals with chronic pain conditions such as [[Chronic Low Back Pain|low back pain]], [[Headache|headaches]], [[Osteoarthritis|arthritis]], orofacial pain, and [[Fibromyalgia|fibromyalgia]]. CBT has also been applied to pain associated with cancer and its treatment.<ref name="p1" /> Although there are no cures, a combination of psychological and physical therapies appears to provide significant benefits. When pain persists in spite of medical treatment, as is the case in chronic pain syndromes, the issues become even more complex. A person who has pain, especially with movement, tends to avoid doing things that provoke their symptoms and choose to rest. Rest is not a helpful treatment as it leads to secondary stiffness and weakness, causing worsening of the symptoms the individual is trying to avoid and leads to the inability to function. The inability to function leads to a loss of role and self-esteem with the progressive intrusion of other problems such as financial hardship and strained relationships. In essence, CBT approaches aim to improve the way that an individual manages and copes with their pain, rather than finding a biological solution to the putative pathology. With appropriate instruction in a range of pacing techniques, cognitive therapy to help identify negative thinking patterns and the development of effective challenges, stretching and exercising to improve physical function, careful planning of tasks and daily activities, and the judicious use of relaxation training, many people find CBT enables them to take back control of their lives, to do more and feel better.<ref name="p4" /> | ||

CBT is commonly addressed by psychologists, but practitioners such as physiotherapists, occupational therapists, nurses and doctors must improve their psychological understanding and skills to contribute to the CBT. For example, an exercise programme run by a physiotherapist will adopt a cognitive approach by ascertaining the person's fears and beliefs about the movement or activity they are undertaking. Frequently this will demonstrate that the person's caution relates to fear of damage. Such an approach will move the person on both physically and psychologically in a way that coercion alone will never achieve.<ref name="p4">C.Pither. Cognitive Behavioral Approaches to Chronic Pain. Available at www.wellcome.ac.uk/en/pain/microsite/medicine3.html</ref> | |||

<br> | |||

== Cognitive Functional Therapy (CFT) | == Cognitive Functional Therapy (CFT) == | ||

[[Image:Fear-avoidance model.jpg|right|400px]] | |||

Cognitive functional therapy (CFT) is a | ''Cognitive functional therapy (CFT)'' is a multilevel client-centred clinical reasoning approach to management that targets the beliefs, fears and associated behaviours (both movement and lifestyle) of each individual with back pain.<ref name="p9" /> This approach focuses on changing patient beliefs, confronting their fears, educating them about pain mechanisms, enhancing mindfulness of the control of their body during pain provocative functional tasks, training them to reduce excessive trunk muscle activity and change behaviours related to pain provocative movements and postures.<ref name="p0" /> | ||

*< | *It leads the person to be mindful that pain is not a reflection of damage – but rather a process where the person is trapped in a vicious cycle of pain and disability.<ref name="p0">M. O'Keeffe, H. Purtill, N. Kennedy, P. O'Sullivan, W. Dankaerts, A. Tighe, L. Allworthy, L. Dolan, N. Bargary, K. O'Sullivan. Individualised cognitive functional therapy compared with a combined exercise and pain education class for patients with non-specific chronic low back pain: study protocol for a multicentre randomised controlled trial.fckLRBMJ Open 2015;5:6 e007156 doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2014-007156</ref> | ||

* | *It is strongly behaviourally orientated and explores different movement options using visual feedback in order for people to reestablish their body schema and relearn the basic building blocks of relaxed normal movement. | ||

* | *It empowers the person to do the very things they fear and / or avoid, but in a graduated relaxed and normal manner. | ||

* | *It conditions them if they are weak. | ||

*It motivates them to engage with exercise and active living based on their preferences and goals.<ref name="p9" /> | |||

{{#ev:youtube|ySJ5O2NnnuE}} | {{#ev:youtube|ySJ5O2NnnuE}}<ref>Bodylogicphysio's channel. Cognitive Functional Therapy with Professor Peter O'Sullivan. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ySJ5O2NnnuE</ref> | ||

This approach is great for management of chronic disorders as it aims to build self-efficacy, confidence, and adaptability while providing hope and opportunity for change for the person with pain in a person-centred manner.<ref name="p9">Classification based cognitive functional therapy for back pain. Available at: http://www.bodyinmind.org/classification-based-cognitive-functional-therapy-for-back-pain/</ref> | |||

=== CFT in Practice === | === CFT in Practice === | ||

The CFT intervention includes | The CFT intervention includes comprehensive ''one-to-one interview'' which involves listening to the full patient story regarding their pain and it is targeted to meet the patients’ individual needs as well fulfilling the ''physical examination ''requirements by the treating physiotherapist. The patient is encouraged to discuss their level of fear of pain and any avoidance of activities, work and social engagement. Then, their beliefs and goals regarding management of their disorder will be ascertained. The physical examination involves analysis of the patient’s primary functional impairments (e.g. pain provocative, feared and/or avoided movements, and functional tasks), in order to identify maladaptive behaviours which include muscle guarding, ‘abnormal’ movements and postures, avoidant patterns and pain behaviours. They will also be assessed regarding their level of body control and awareness (body perception), as well as their ability to relax their trunk muscles and normalise pain provocative postural and movement behaviours, and the effect these on their pain.<ref name="p0" /> | ||

{{#ev:youtube|jgwg-CD_Q8A}} | {{#ev:youtube|jgwg-CD_Q8A}}<ref>Pain-Ed.com. Can CFT (Cognitive Functional Therapy) work in typical clinical practice - speaking to clinicians. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jgwg-CD_Q8A</ref> | ||

== Therapeutic Neuroscience Education (TNE) == | |||

= | Traditional medicine is strongly rooted in a biomedical model, which assumes that injury and pain are the same issue. Therefore, an increase in pain means increased tissue injury and increased tissue injuries lead to more pain. This model (called the Cartesian model of pain) is over 350 years old, and it's incorrect.<ref name="p5">Therapeutic Neuroscience Education: Teaching People About Pain. Institute for Chronic Pain. Available at: http://www.instituteforchronicpain.org/treating-common-pain/what-is-pain-management/therapeutic-neuroscience-education</ref> Words like "bulging," "herniated," "rupture" and "tear" increase anxiety and make people less interested in movement, which is essential for recovery. This is especially important when pain persists for long periods. Most tissues in the human body heal between 3-6 months, but it is now well established that ongoing pain is more due to a sensitive nervous system. In other words, the body’s alarm system stays activated even after tissues have healed.<ref name="p5" /> | ||

Over the last 10 years, a research team from International Spine and Pain Institute and Therapeutic Neuroscience Research Group has explored one such potential cause and set in motion a variety of research projects aimed at teaching people more about pain. Learning the biological processes of pain is called neuroscience education (the science of nerves).<ref name="p5" /> | |||

[[Pain Neuroscience Education (PNE)|''Therapeutic neuroscience education (TNE)'']] has been shown to be effective in the treatment of mainly chronic musculoskeletal pain conditions.<ref name="p6">A. Louw, Emilio J. Puentedura, I. Diener & Randal R. Peoples. Preoperative therapeutic neuroscience education for lumbar radiculopathy: a single-case fMRI report. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice: An International Journal of Physiotherapy. Volume 31, Issue 7, 2015</ref> Emerging research shows that explaining to patients their pain experience from a biological and physiological perspective of how the nervous system/brain processes pain<ref name="p7">A. Louw. Therapeutic Neuroscience Education: Teaching People About Pain. American Academy of Pain Management. September 2014</ref> allows them to produce some impressive immediate and long-term changes, such as... | |||

*Decreased pain | |||

*Improved function | |||

*Diminished fear | |||

*More positive thoughts about pain | |||

*Increased pain knowledge | |||

*Improved movement | |||

*Improved muscle functioning | |||

*Less money spent on medical tests and treatments | |||

*Increased calming of the brain (as seen on brain scans) | |||

*Increased willingness to do much-needed exercise<ref name="p5" /> | |||

=== TNE in Practice === | |||

< | TNE changes a patient’s perception of pain. With TNE, the patient understands that pain may not correctly represent the health of the tissue, but may be more due to extra-sensitive nerves. Simply stated, they understand they may have a pain problem rather than a tissue problem. This neuroscience view of sensitive nerves versus tissue injury allows for a new, understandable view of treatments aimed at easing nerve sensitivity, such as aerobic exercise, manual therapy, relaxation, deep breathing, sleep hygiene, diet and more.<ref name="p5" /> | ||

A multidisciplinary approach to pain management utilizing multiple treatment modalities provides benefits to patients, healthcare providers and society as a whole. Pain management including behavioural modification therapy significantly improves patients' chronic pain symptoms evidenced by a decrease in the use of medications and improved functional ability, likelihood of returning to work, patient care, and patient satisfaction. These factors lead to reduced healthcare costs.<ref name="p3">J.Pergolizzi. Towards a Multidisciplinary Team Approach in Chronic Pain Management. PDF book available at www.pae-eu.eu</ref> | |||

== References == | == References == | ||

| Line 91: | Line 76: | ||

<references /> | <references /> | ||

[[Category:Pain]] [[Category:PPA_Project]] | [[Category:Pain]] | ||

[[Category:PPA_Project]] | |||

[[Category:Older People/Geriatrics]] | |||

[[Category:Course Pages]] | |||

Latest revision as of 18:09, 22 June 2022

Original Editor - Elvira Muhic

Top Contributors - Elvira Muhic, Lauren Lopez, Evan Thomas, Laura Ritchie, Jess Bell, Jo Etherton, Angela Patterson, 127.0.0.1, Michelle Lee and WikiSysop

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT)[edit | edit source]

Whether assessing or treating acute or chronic pain syndromes, pain management should include a biopsychosocial approach. Assessment may include a focused joint and functional examination including more global areas of impairment (i.e. gait, balance, and endurance) and disability.[1]

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) can be described as the "gold standard" psychological treatment for individuals with a wide range of pain problems. It can be used alone or in conjunction with medical or interdisciplinary rehabilitation treatments.[2]

Chronic pain stands-out as the most common condition treated with CBT. The reason for this, as the Institute of Medicine[3] explains, is because chronic pain is a condition influenced by biological, psychological, and social factors and is optimally managed by treatments that address not only its biological causes but also its psychological and social influences and consequences.[2] Since the introduction of the biopsychosocial model, treatment for chronic pain has become multi-modal and multidisciplinary, with emphasis on a range of strategies aimed at maximising pain reduction, improving health-related quality of life, independence and mobility, enhancing psychological well-being and preventing secondary dysfunction.[4]

As time goes by, a patient with pain can develop behaviours, such as pain catastrophising (magnification of the threat of, rumination about, and perceived inability to cope with pain), as well as fear-avoidance (activity avoidance due to fear of increased pain or bodily harm), which have consistently been found to be associated with greater physical and psychosocial dysfunction, even after controlling for pain and depression levels.[5][6][7][8] Individuals experiencing chronic pain may have mood, anxiety, and sleep disorders, and CBT can also be used to treat these conditions.[2]

CBT in Practice[edit | edit source]

There is no standard protocol for CBT; it varies in the number of sessions and specific techniques used. CBT for pain often includes relaxation training, setting and working toward behavioral goals such as increases in exercise and other activities, behavioural activation, guidance in activity pacing, problem-solving training, and cognitive restructuring.[2]

Currently, CBT is the prevailing psychological treatment for individuals with chronic pain conditions such as low back pain, headaches, arthritis, orofacial pain, and fibromyalgia. CBT has also been applied to pain associated with cancer and its treatment.[2] Although there are no cures, a combination of psychological and physical therapies appears to provide significant benefits. When pain persists in spite of medical treatment, as is the case in chronic pain syndromes, the issues become even more complex. A person who has pain, especially with movement, tends to avoid doing things that provoke their symptoms and choose to rest. Rest is not a helpful treatment as it leads to secondary stiffness and weakness, causing worsening of the symptoms the individual is trying to avoid and leads to the inability to function. The inability to function leads to a loss of role and self-esteem with the progressive intrusion of other problems such as financial hardship and strained relationships. In essence, CBT approaches aim to improve the way that an individual manages and copes with their pain, rather than finding a biological solution to the putative pathology. With appropriate instruction in a range of pacing techniques, cognitive therapy to help identify negative thinking patterns and the development of effective challenges, stretching and exercising to improve physical function, careful planning of tasks and daily activities, and the judicious use of relaxation training, many people find CBT enables them to take back control of their lives, to do more and feel better.[9]

CBT is commonly addressed by psychologists, but practitioners such as physiotherapists, occupational therapists, nurses and doctors must improve their psychological understanding and skills to contribute to the CBT. For example, an exercise programme run by a physiotherapist will adopt a cognitive approach by ascertaining the person's fears and beliefs about the movement or activity they are undertaking. Frequently this will demonstrate that the person's caution relates to fear of damage. Such an approach will move the person on both physically and psychologically in a way that coercion alone will never achieve.[9]

Cognitive Functional Therapy (CFT)[edit | edit source]

Cognitive functional therapy (CFT) is a multilevel client-centred clinical reasoning approach to management that targets the beliefs, fears and associated behaviours (both movement and lifestyle) of each individual with back pain.[10] This approach focuses on changing patient beliefs, confronting their fears, educating them about pain mechanisms, enhancing mindfulness of the control of their body during pain provocative functional tasks, training them to reduce excessive trunk muscle activity and change behaviours related to pain provocative movements and postures.[11]

- It leads the person to be mindful that pain is not a reflection of damage – but rather a process where the person is trapped in a vicious cycle of pain and disability.[11]

- It is strongly behaviourally orientated and explores different movement options using visual feedback in order for people to reestablish their body schema and relearn the basic building blocks of relaxed normal movement.

- It empowers the person to do the very things they fear and / or avoid, but in a graduated relaxed and normal manner.

- It conditions them if they are weak.

- It motivates them to engage with exercise and active living based on their preferences and goals.[10]

This approach is great for management of chronic disorders as it aims to build self-efficacy, confidence, and adaptability while providing hope and opportunity for change for the person with pain in a person-centred manner.[10]

CFT in Practice[edit | edit source]

The CFT intervention includes comprehensive one-to-one interview which involves listening to the full patient story regarding their pain and it is targeted to meet the patients’ individual needs as well fulfilling the physical examination requirements by the treating physiotherapist. The patient is encouraged to discuss their level of fear of pain and any avoidance of activities, work and social engagement. Then, their beliefs and goals regarding management of their disorder will be ascertained. The physical examination involves analysis of the patient’s primary functional impairments (e.g. pain provocative, feared and/or avoided movements, and functional tasks), in order to identify maladaptive behaviours which include muscle guarding, ‘abnormal’ movements and postures, avoidant patterns and pain behaviours. They will also be assessed regarding their level of body control and awareness (body perception), as well as their ability to relax their trunk muscles and normalise pain provocative postural and movement behaviours, and the effect these on their pain.[11]

Therapeutic Neuroscience Education (TNE)[edit | edit source]

Traditional medicine is strongly rooted in a biomedical model, which assumes that injury and pain are the same issue. Therefore, an increase in pain means increased tissue injury and increased tissue injuries lead to more pain. This model (called the Cartesian model of pain) is over 350 years old, and it's incorrect.[14] Words like "bulging," "herniated," "rupture" and "tear" increase anxiety and make people less interested in movement, which is essential for recovery. This is especially important when pain persists for long periods. Most tissues in the human body heal between 3-6 months, but it is now well established that ongoing pain is more due to a sensitive nervous system. In other words, the body’s alarm system stays activated even after tissues have healed.[14]

Over the last 10 years, a research team from International Spine and Pain Institute and Therapeutic Neuroscience Research Group has explored one such potential cause and set in motion a variety of research projects aimed at teaching people more about pain. Learning the biological processes of pain is called neuroscience education (the science of nerves).[14]

Therapeutic neuroscience education (TNE) has been shown to be effective in the treatment of mainly chronic musculoskeletal pain conditions.[15] Emerging research shows that explaining to patients their pain experience from a biological and physiological perspective of how the nervous system/brain processes pain[16] allows them to produce some impressive immediate and long-term changes, such as...

- Decreased pain

- Improved function

- Diminished fear

- More positive thoughts about pain

- Increased pain knowledge

- Improved movement

- Improved muscle functioning

- Less money spent on medical tests and treatments

- Increased calming of the brain (as seen on brain scans)

- Increased willingness to do much-needed exercise[14]

TNE in Practice[edit | edit source]

TNE changes a patient’s perception of pain. With TNE, the patient understands that pain may not correctly represent the health of the tissue, but may be more due to extra-sensitive nerves. Simply stated, they understand they may have a pain problem rather than a tissue problem. This neuroscience view of sensitive nerves versus tissue injury allows for a new, understandable view of treatments aimed at easing nerve sensitivity, such as aerobic exercise, manual therapy, relaxation, deep breathing, sleep hygiene, diet and more.[14]

A multidisciplinary approach to pain management utilizing multiple treatment modalities provides benefits to patients, healthcare providers and society as a whole. Pain management including behavioural modification therapy significantly improves patients' chronic pain symptoms evidenced by a decrease in the use of medications and improved functional ability, likelihood of returning to work, patient care, and patient satisfaction. These factors lead to reduced healthcare costs.[4]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Steven P. Stanos, James McLean, Lynn Rader. Physical Medicine Rehabilitation Approach to Pain. Medical Clinics of North America, Volume 91, Issue 1, Pages 57-95. 2007

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Dawn M. Ehde, Tiara M. Dillworth, and Judith A. Turner. Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Individuals With Chronic Pain - Efficacy, Innovations, and Directions for Research. University of Washington. February-March 2014

- ↑ Institute of Medicine. Clinical practice guidelines we can trust. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2011. Accessed 30 August 2019.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 J.Pergolizzi. Towards a Multidisciplinary Team Approach in Chronic Pain Management. PDF book available at www.pae-eu.eu

- ↑ Edwards RR, Cahalan C, Mensing G, Smith M, Haythornthwaite JA. Pain, catastrophizing, and depression in the rheumatic diseases. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2011 Apr;7(4):216-24.

- ↑ Phillip J Quartana, PhD, Claudia M Campbell, PhD, and Robert R Edwards. Pain catastrophizing: a critical review. Expert Rev Neurother. 2009. 9;5: 745–758. Accessed 30 August 2019.

- ↑ Gatchel RJ, Peng YB, Peters ML, Fuchs PN, Turk DC. The biopsychosocial approach to chronic pain: scientific advances and future directions. Psychol Bull. 2007 Jul;133(4):581-624.

- ↑ Leeuw M, Goossens M, Linton S, Crombez G, Boersma K, Vlaeyen J. The Fear-Avoidance Model of Musculoskeletal Pain: Current State of Scientific Evidence. Journal of behavioral medicine. 2007 30. 77-94. Accessed 30 August 2019.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 C.Pither. Cognitive Behavioral Approaches to Chronic Pain. Available at www.wellcome.ac.uk/en/pain/microsite/medicine3.html

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Classification based cognitive functional therapy for back pain. Available at: http://www.bodyinmind.org/classification-based-cognitive-functional-therapy-for-back-pain/

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 M. O'Keeffe, H. Purtill, N. Kennedy, P. O'Sullivan, W. Dankaerts, A. Tighe, L. Allworthy, L. Dolan, N. Bargary, K. O'Sullivan. Individualised cognitive functional therapy compared with a combined exercise and pain education class for patients with non-specific chronic low back pain: study protocol for a multicentre randomised controlled trial.fckLRBMJ Open 2015;5:6 e007156 doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2014-007156

- ↑ Bodylogicphysio's channel. Cognitive Functional Therapy with Professor Peter O'Sullivan. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ySJ5O2NnnuE

- ↑ Pain-Ed.com. Can CFT (Cognitive Functional Therapy) work in typical clinical practice - speaking to clinicians. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jgwg-CD_Q8A

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 Therapeutic Neuroscience Education: Teaching People About Pain. Institute for Chronic Pain. Available at: http://www.instituteforchronicpain.org/treating-common-pain/what-is-pain-management/therapeutic-neuroscience-education

- ↑ A. Louw, Emilio J. Puentedura, I. Diener & Randal R. Peoples. Preoperative therapeutic neuroscience education for lumbar radiculopathy: a single-case fMRI report. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice: An International Journal of Physiotherapy. Volume 31, Issue 7, 2015

- ↑ A. Louw. Therapeutic Neuroscience Education: Teaching People About Pain. American Academy of Pain Management. September 2014