Hip Osteoarthritis: Difference between revisions

Leana Louw (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

Leana Louw (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

== Definition/Description == | == Definition/Description == | ||

[[Osteoarthritis]] is a condition | [[Osteoarthritis]] is a degenerative condition as a result of mechanical overload in a weight bearing joint.<ref name=":0">Murphy NJ, Eyles JP, Hunter DJ. Hip osteoarthritis: etiopathogenesis and implications for management. Advances in therapy 2016;33(11):1921-46.</ref> Hip osteoarthritis mainly affects the articular cartilage, as well as causing changes to the subcondral bone, synovium, ligaments and capsule.<ref name=":6">Cooper C, Javaid MK, Arden N. Epidemiology of osteoarthritis. In: Atlas of Osteoarthritis. Tarporley: Springer Healthcare, 2014. p22.</ref> This degeneration lead to loss of joint space, which can potentially be symptomatic.<ref name=":6" /> It is one of the top 15 contributors of global disability.<ref>Cross M, Smith E, Hoy, Nolte S, Ackerman I, Fransen M, Bridgett L, Williams S, Guillemin F, Hill CL, Laslett LL, Jones G, Cicuttini F, Osborne R, Vos T, Buchbinder R, Woolf A, March L. The global burden of hip and knee osteoarthritis: estimates from the Global Burden of Disease 2010 study. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 2014;73:1323-1330.</ref> Hip osteoarthritis is prevalent in 10% of people above 65, where 50% of these cases are symptomatic.<ref name=":7">Nüesch E, Dieppe P, Reichenbach S, Williams S, Iff S, Jüni P. All cause and disease specific mortality in patients with knee or hip osteoarthritis: population based cohort study. Bmj 2011;342:1165.</ref> The hip is defined as the second most painful joint (after the knee) as a result of osteoarthritis according to a Italian study.<ref>Cimmino MA, Sarzi-Puttini P, Scarpa R, Caporali R, Parazzini F, Zaninelli A, Marcolongo R. Clinical presentation of osteoarthritis in general practice: determinants of pain in Italian patients in the AMICA study. Seminars in arthritis and rheumatism 2005;35(1):17-23).</ref> | ||

== Clinically relevant anatomy == | == Clinically relevant anatomy == | ||

| Line 23: | Line 23: | ||

=== Primary osteoarthritis === | === Primary osteoarthritis === | ||

Mostly caused by abnormality of the articular cartilage, but can also be a secondary result of developmental changes and abnormalities such as femeroacetbular impingement.<ref name=":8">Ganz R, Leunig M, Leunig-Ganz K, Harris WH. The etiology of osteoarthritis of the hip. Clinical orthopaedics and related research 2008;466(2):264-72.</ref> Abnormalities normally include acetabular displasia. Pistol grip deformities are seen in some cases, mostly linked with slipped upper femoral epiphysis. Although seen as a specific condition, it is often linked with metabolic abnormalities.<ref>Harris WH. Etiology of osteoarthritis of the hip. Clinical orthopaedics and related research 1986; 213:20-33.</ref> | Mostly caused by abnormality of the articular cartilage, but can also be a secondary result of developmental changes and abnormalities such as femeroacetbular impingement.<ref name=":8">Ganz R, Leunig M, Leunig-Ganz K, Harris WH. The etiology of osteoarthritis of the hip. Clinical orthopaedics and related research 2008;466(2):264-72.</ref> Abnormalities normally include acetabular displasia. Pistol grip deformities are seen in some cases, mostly linked with [[Slipped Capital Femoral Epiphysis|slipped upper femoral epiphysis]]. Although seen as a specific condition, it is often linked with metabolic abnormalities.<ref>Harris WH. Etiology of osteoarthritis of the hip. Clinical orthopaedics and related research 1986; 213:20-33.</ref> | ||

=== Secondary osteoarthritis === | === Secondary osteoarthritis === | ||

| Line 39: | Line 39: | ||

*Increase in age | *Increase in age | ||

*Gender (female > male) | *Gender (female > male) | ||

*Sport (higher impact sport at a younger age can cause increase in articular cartilage strength, where low impact sport do | *Sport (higher impact sport at a younger age can cause increase in articular cartilage strength, where low impact sport do not change the composition of the cartilage) | ||

*Menopause | *Menopause | ||

*Metabolic diseases and acromegaly | *Metabolic diseases and acromegaly | ||

| Line 54: | Line 54: | ||

* [[Pain]]: | * [[Pain]]: | ||

** Progressively increasing | ** Progressively increasing | ||

** Aggravated - movement; when hip is loaded wrong or too long; cold | ** Aggravated - movement; when hip is loaded wrong or too long; cold weather | ||

** Eased with continuous | ** Eased with continuous movement | ||

** Commonly in groin/thigh radiating to buttocks or knee | ** Commonly in groin/thigh, radiating to buttocks or knee | ||

** End-stage: Constant pain, night pain | ** End-stage: Constant pain, night pain | ||

* Stiffness: | * Stiffness: | ||

** Morning stiffness with end-stage osteoarthritis, usually eased with movement | ** Morning stiffness with end-stage osteoarthritis, usually eased with movement (<1 hour) | ||

* "Locking" of hip movement | * "Locking" of hip movement | ||

* Decreased rang of motion - leading to joint contractures and muscle atrophy | * Decreased rang of motion - leading to joint contractures and muscle atrophy | ||

| Line 91: | Line 91: | ||

== Diagnostic procedures == | == Diagnostic procedures == | ||

{{#ev:youtube|8xrDWgIUMO4}}<ref>Physiotutors. Cluster of Sutlive | Hip Osteoarthritis Diagnostic Cluster. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8xrDWgIUMO4</ref> | |||

The American College of Rheumatology published criteria in 1990 for the diagnosis of hip osteoarthritis:<ref name=":0" /> | The American College of Rheumatology published criteria in 1990 for the diagnosis of hip osteoarthritis:<ref name=":0" /> | ||

| Line 116: | Line 118: | ||

Hip osteoarthritis can be diagnosed by clinical presentation only, but special investigation (e.g. x-rays) are vital to monitor the progression of the disease. | Hip osteoarthritis can be diagnosed by clinical presentation only, but special investigation (e.g. x-rays) are vital to monitor the progression of the disease. | ||

* '''X-rays:''' Findings include joint space narrowing, marginal osteophytes, subchondral sclerosis, and bone cysts.<ref>Brandt CD. Diagnosis and non-surgical management of osteoarthritis. USA: Professional Communications, Inc. 2010.</ref> This is normally the first investigation done that aids in the diagnosis of hip osteoarthritis | * '''X-rays:''' Findings include joint space narrowing, marginal osteophytes, subchondral sclerosis, and bone cysts.<ref>Brandt CD. Diagnosis and non-surgical management of osteoarthritis. USA: Professional Communications, Inc. 2010.</ref> This is normally the first investigation done that aids in the diagnosis of hip osteoarthritis. | ||

* '''[[MRI Scans|MRI]]:''' More effective in detecting early change in the bone structure, such as focal cartilage defects and bone marrow lesions in the subchondral bone.<ref name=":1">Bennell K. Physiotherapy management of hip osteoarthritis. J Physiother. 2013; 59(3):145–157.</ref> | * '''[[MRI Scans|MRI]]:''' More effective in detecting early change in the bone structure, such as focal cartilage defects and bone marrow lesions in the subchondral bone.<ref name=":1">Bennell K. Physiotherapy management of hip osteoarthritis. J Physiother. 2013; 59(3):145–157.</ref> | ||

* '''[[CT Scans|CT scan]]''' | * '''[[CT Scans|CT scan]]''' | ||

| Line 169: | Line 171: | ||

==== [[Total Hip Replacement|Total hip replacement]] ==== | ==== [[Total Hip Replacement|Total hip replacement]] ==== | ||

90% of total hip replacements are done as a result of end-stage hip osteoarthritis. It is a successful orthopaedic procedure in the treatment of hip osteoarthritis, when | 90% of total hip replacements are done as a result of end-stage hip osteoarthritis. It is a successful orthopaedic procedure in the treatment of hip osteoarthritis, when conservative management has failed and is highly effective at relieving symptoms. | ||

==== Hip resurfacing ==== | ==== Hip resurfacing ==== | ||

| Line 175: | Line 177: | ||

==== [[Osteotomy|Hip osteotomy]] ==== | ==== [[Osteotomy|Hip osteotomy]] ==== | ||

An osteotomy is preformed to realign the hip joint to lessen pressure. This is not a common | An osteotomy is preformed to realign the hip joint to lessen pressure. This is not a common in the treatment of osteoarthritis. | ||

== Examination == | == Examination == | ||

| Line 187: | Line 189: | ||

* Problems with your gait (the way you walk) | * Problems with your gait (the way you walk) | ||

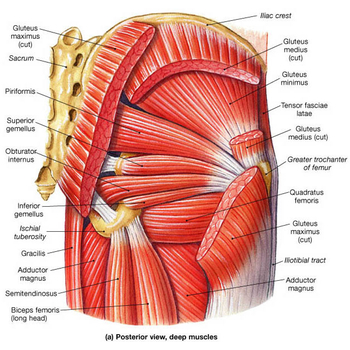

* Any signs of injury to the muscles, tendons, and ligaments surrounding the hip | * Any signs of injury to the muscles, tendons, and ligaments surrounding the hip | ||

<span lang="EN-US" style="font-family: arial">The beginning of OA is characterized by limited abduction and </span>rotation in the hip joint. Later on flexion, extension, and adduction become more difficult.<br>Physiotherapeutic examination <ref>CRIELAND, e.a., Osteoartrose, Lichtert, Brussel, 1985</ref><br><br>1) Palpation of M. gluteus medius.<br> Position: patient lies on his side. Upper leg in adduction and flexion<br> OA: Zone of greater Trochanter is sensitive and painful.<br> | <span lang="EN-US" style="font-family: arial">The beginning of OA is characterized by limited abduction and </span>rotation in the hip joint. Later on flexion, extension, and adduction become more difficult.<br>Physiotherapeutic examination <ref>CRIELAND, e.a., Osteoartrose, Lichtert, Brussel, 1985</ref><br><br>1) Palpation of M. gluteus medius.<br> Position: patient lies on his side. Upper leg in adduction and flexion<br> OA: Zone of greater Trochanter is sensitive and painful.<br> | ||

Revision as of 00:35, 15 July 2018

Original Editor - Eric Robertson, Kim Presiaux

Top Contributors - Kim Presiaux, Dorien De Strijcker, Lucinda hampton, Davy Duverger, Leana Louw, Kim Jackson, Johnathan Fahrner, Admin, Rachael Lowe, Laura Ritchie, Scott Buxton, Van Horebeek Erika, Vidya Acharya, Kai A. Sigel, Eric Robertson, Areeba Raja, Loïc Byl, Marius De Bruyn, Kevin Vandebroucq, Bram Van Roost, 127.0.0.1, Shaimaa Eldib and Lauren Lopez

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

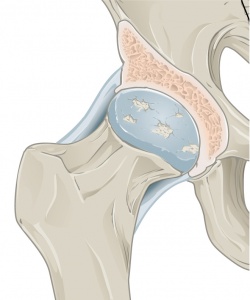

Osteoarthritis is a degenerative condition as a result of mechanical overload in a weight bearing joint.[1] Hip osteoarthritis mainly affects the articular cartilage, as well as causing changes to the subcondral bone, synovium, ligaments and capsule.[2] This degeneration lead to loss of joint space, which can potentially be symptomatic.[2] It is one of the top 15 contributors of global disability.[3] Hip osteoarthritis is prevalent in 10% of people above 65, where 50% of these cases are symptomatic.[4] The hip is defined as the second most painful joint (after the knee) as a result of osteoarthritis according to a Italian study.[5]

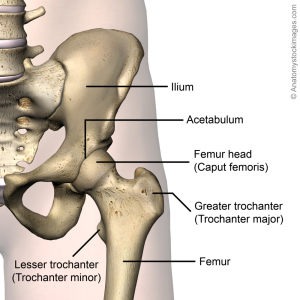

Clinically relevant anatomy[edit | edit source]

For detailed information, see the hip anatomy page.

Epidemiology & etiology[edit | edit source]

Prevalence[edit | edit source]

Hip osteoarthritis is prevalent in 10% of people above 65, where 50% of these cases are symptomatic.[4] Research suggest that there are a 25% risk of developing hip osteoarthritis for people who live to the age of 85,[1]

Primary osteoarthritis[edit | edit source]

Mostly caused by abnormality of the articular cartilage, but can also be a secondary result of developmental changes and abnormalities such as femeroacetbular impingement.[6] Abnormalities normally include acetabular displasia. Pistol grip deformities are seen in some cases, mostly linked with slipped upper femoral epiphysis. Although seen as a specific condition, it is often linked with metabolic abnormalities.[7]

Secondary osteoarthritis[edit | edit source]

Secondary osteoarthritis is caused by predisposing anatomic abnormalities such as developmental or congenital deformities.[6][8]

Risk factors[edit | edit source]

- Previous hip trauma (causing injury or fracture) - mostly resulting in unilateral hip osteoarthritis

- Primary inflammatory arthritis (e.g. rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis)

- Joint morphology

- Genetics

- Congenital and developmental hip disease (e.g. congenital hip dislocation, Perthe's disease, slipped upper femoral epiphysis, developmental hip dysplasia)

- Subchondral bone defects

- Obesity - mostly resulting in bilateral hip osteoarthritis

- Occupation causing excessive strain on hips (e.g. manual labor causing repeated loading)

- Increase in age

- Gender (female > male)

- Sport (higher impact sport at a younger age can cause increase in articular cartilage strength, where low impact sport do not change the composition of the cartilage)

- Menopause

- Metabolic diseases and acromegaly

- Sedentary lifestyle

- Femoroacetabular impingement

- Avascular necrosis

- Ethnicity - 80-90% less prevalent in the Asian population when compared to the Caucasian population in the USA

- Diet - low Vitamin D, C and K levels

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Signs & symptoms:[10][11][12][13]

- Pain:

- Progressively increasing

- Aggravated - movement; when hip is loaded wrong or too long; cold weather

- Eased with continuous movement

- Commonly in groin/thigh, radiating to buttocks or knee

- End-stage: Constant pain, night pain

- Stiffness:

- Morning stiffness with end-stage osteoarthritis, usually eased with movement (<1 hour)

- "Locking" of hip movement

- Decreased rang of motion - leading to joint contractures and muscle atrophy

- Crepitis with movement

- Gait abnormalities - short limb gait, antalgic gait, trendelenburg gait, stiff hip gait

- Leg length discrepancy

- Local inflammation

Differential diagnosis[14][edit | edit source]

- Muscle contusion

- Muscle strains - gluteus and adductors

- Athletic pubalgia

- Piriformis syndrome

- Hamstring syndrome

- Inflammatory disorders

- Snapping hip syndrome

- Hip bursitis

- Arthritis

- Septic arthritis of the hip

- Avascular necrosis

- Labral tears

- Hip fractures

- Hip dislocations

- Tumors

- Chondral defect

- Ligamentus teres injury

- Sciatica

- Nerve irritation (especially obturator & lateral femoral cutaneous)

- Joint capsule disorders

- Inguinal ligament strain

Diagnostic procedures[edit | edit source]

The American College of Rheumatology published criteria in 1990 for the diagnosis of hip osteoarthritis:[1]

Clinical criteria A

- Hip pain

- Hip internal rotation <15°

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) ≤45mm/h OR hip flexion ≤115° if ESR not available

Clinical criteria B

- Hip pain

- Pain with hip internal rotation

- Morning stiffness ≤1 hour

- >50 years

Clinical plus radiographic criteria

- Hip pain

- Two of the following:

- ESR <20mm/h

- Osteophytes on hip x-rays

- Joint space narrowing on x-rays

Special investigations[edit | edit source]

Hip osteoarthritis can be diagnosed by clinical presentation only, but special investigation (e.g. x-rays) are vital to monitor the progression of the disease.

- X-rays: Findings include joint space narrowing, marginal osteophytes, subchondral sclerosis, and bone cysts.[16] This is normally the first investigation done that aids in the diagnosis of hip osteoarthritis.

- MRI: More effective in detecting early change in the bone structure, such as focal cartilage defects and bone marrow lesions in the subchondral bone.[17]

- CT scan

- Bone scan: Aids in assessing the condition of soft tissue and bone of the hip

Outcome measures[edit | edit source]

- Patient acceptable symptom state (PASS)

- Visual analogue scale (VAS)

- Hip disability and osteoarthritis outcome score (HOOS)

- Western Ontario and McMaster universities osteoarthritis index (WOMAC)

- Harris hip score

- Oxford hip score (OHS)

- Algofunctional index (AFI)

- Intermittent and constant osteoarthritis pain index (ICOAP)

- Lequesne index

- 6 Minute Walking Test

- Timed up and go test

- patients specific complaints list (PSC)

- SF-36

- Fear Avoidance Belief Score

- International Hip Outcome Tool

- Ibadan Knee/Hip Osteoarthritis Outcome Measure

Medical management[edit | edit source]

Medical management of hip osteoarthritis focuses on treating the symptoms. Effective disease-modifying interventions have not been estabilished yet, thus a major focus should be on primary prevention strategies.[1]

Primary prevention[edit | edit source]

- Patient education - especially in primary health care

- Muscle strengthening

- Joint preserving surgery prior to onset of hip osteoarthritis/early in disease process

- Modification of risk factors:

- Weight control

- Switching from high-impact to low-impact activities

- Minimization of pain aggravating activities

Pharmacological management[1][edit | edit source]

- Symptom-relief drugs:

- Start with paracetamol

- NSAIDs - low doses and duration due to side effects

- Duloxetine - works on central nervous system to inhibit pain

- Tramadol (non-narcotic opioid)

- Intra-articular injections:

- Corticosteroids

- Platelet-rich plasma

- Hyaluronic acid

- Disease-modifying osteoarthritis drugs (research on this topic still ongoing)

Surgical intervention[edit | edit source]

Total hip replacement[edit | edit source]

90% of total hip replacements are done as a result of end-stage hip osteoarthritis. It is a successful orthopaedic procedure in the treatment of hip osteoarthritis, when conservative management has failed and is highly effective at relieving symptoms.

Hip resurfacing[edit | edit source]

This is normally done for the younger, more active population.

Hip osteotomy[edit | edit source]

An osteotomy is preformed to realign the hip joint to lessen pressure. This is not a common in the treatment of osteoarthritis.

Examination[edit | edit source]

Physical Examination[edit | edit source]

During the physical examination, your doctor will look for:

- Tenderness about the hip

- Range of passive (assisted) and active (self-directed) motion

- Crepitus (a grating sensation inside the joint) with movement

- Pain when pressure is placed on the hip

- Problems with your gait (the way you walk)

- Any signs of injury to the muscles, tendons, and ligaments surrounding the hip

The beginning of OA is characterized by limited abduction and rotation in the hip joint. Later on flexion, extension, and adduction become more difficult.

Physiotherapeutic examination [18]

1) Palpation of M. gluteus medius.

Position: patient lies on his side. Upper leg in adduction and flexion

OA: Zone of greater Trochanter is sensitive and painful.

2)Flexion and forced flexion

Position: patient lies on his back. The physiotherapist lifted one leg to flexion. The knee is

in flexion so there is not too much muscle tension. The pelvis has to be at the same place.

OA: Flexion is limited for the final degrees.[19]

3) Extension

Position: 1. Patient stands in prone. Physiotherapist stabilizes the pelvis and raises the

leg. or 2. patient lies on his chest and lift the leg with flexion in the knee. You need a

flexion in the knee for a lower tension from the muscles

OA: Amplitude is limited.

4) Abduction

Position: Patient lies on his back. Physiotherapist stabilizes the pelvis and

performs abduction.

OA: abduction is limited and painful when the physiotherapist goes to the final degrees.

5) Adduction

Position: Patient lies on his back. The physiotherapist lift one leg and performs an

adduction with the other leg. The leg has to be in a normal position, no rotations.

OA: Keeps normal amplitude.[20][21]

Hip osteoarthritis can be diagnosed by a combination of the findings from a history and physical examination, so we don’t need to expose the patient to unnecessary radiation in an X-ray. The most used criteria in the diagnosis of hip osteoarthritis are those from the

American College of Rheumatology, which includes two sets of clinical features.[17]

Clinical Set A:

- Age: 50+

- Hip pain

- Hip internal rotation ≥ 15 degrees

- Pain with hip internal rotation

- Morning stiffness of the hip less than 60min

Clinical Set B:

- Age: 50+

- Hip pain

- Hip internal rotation < 15 degrees

Hip flexion ≤ 115 degrees

Later on, Sutlive et al. published a list of variables for detecting hip osteoarthritis in patients with unilateral hip pain. If there are 3 present variables out of the list of 5 variables, the chance of having OA is 68%. With 4 or 5 variables that are noticed, the

chance increases to 91%. The variables are positive when there’s pain or a limited range of motion in the tests.[22]

The five variables are:

- Flexion

- Internal rotation

- Scour test: external and internal rotation in abduction and adduction of the hip.

- Patrick’s or FABER test: flexion,abduction and external rotation of the hip.

- Hip flexion test

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

Rehabilitation for hip OA encompasses several different aspects, including patient education, weight management, land- and water-based exercise, and strength training [144]. While consistent evidence supports the efficacy of these strategies in the management of knee OA [145], the evidence in hip OA is far more variable [144]. Weight loss is recommended for people with hip OA who are overweight/obese; however unlike knee OA, there is a paucity of clinical trial evidence for weight loss in hip OA [146]. A cohort study reported that a combined dietary and exercise weight loss program improved functional symptoms and reduced pain [147]; however, much further study is needed to establish the efficacy of weight loss in hip OA conclusively.

Exercise therapy is widely recommended in clinical guidelines for hip OA management [5, 6, 7]. Overall there is evidence that exercise offers small to moderate benefit in reducing pain and improving function in hip OA [146, 148, 149], although the strength of this evidence is less than for knee OA [150]. Small clinical trials have recently suggested exercise therapy may postpone the need for THA [151] and may reduce medical expenditure for people with hip OA [152]. There are various activities included under the banner of exercise therapy, including strengthening, aerobic, and flexibility activities, many of which can be carried out on land or in the water. No particular activity type has been shown to produce superior results, and thus it is recommended that exercise programs be personalized to reflect the unique needs of each patient [153].

Physiotherapy for hip OA usually includes physiotherapist-led exercise therapies in conjunction with manual therapy. The value of physiotherapy in the management of hip OA is a hotly contested issue, with recent evidence suggesting it offers little benefit beyond what could be expected from a self-guided exercise program [149]. Systematic reviews on the topic have reported no benefit from the use of manual therapy in treating hip OA, nor any additional benefit when manual therapy is combined with an exercise program than is obtained from exercise alone [154, 155]. A recent clinical trial comparing physiotherapy-led management to sham therapy found no benefit of physiotherapy on pain or function [156]. More high-quality research is needed in this area, but the limited evidence currently available does not establish physiotherapy as effective in treating hip OA. A novel strategy being investigated for a potential role in modifying biomechanics to treat hip OA is bracing, although this research is still very much in its infancy [157, 158, 159, 160].

Physical therapy. Specific exercises can help increase range of motion and flexibility, as well as strengthen the muscles in your hip and leg. Your doctor or physical therapist can help develop an individualized exercise program that meets your needs and lifestyle.

Assistive devices. Using walking supports like a cane, crutches, or a walker can improve mobility and independence. Using assistive aids like a long-handled reacher to pick up low-lying things will help you avoid movements that may cause pain.

amercian

A thorough patient history and physical examination should aid a therapist in making his differential diagnosis. Patients will often come to the physiotherapist, complaining they have some pain issues. Pain location often gives a good indication whether it’s an intra-articular or extra-articular disorder.

A systematic review by Bennel (2013) found that treatment goals should be made in cooperation between therapist and patient.[17] The therapy must be centered and applied around the patient. This way it suggests that the patients experience less anxiety to handle with the symptoms even though the condition may not always improve. The review states that patients using a self-management strategy have no difference in pain or function.[17]

Exercise Therapy[edit | edit source]

Currently the amount of research on exercise therapy for patients with hip osteoarthritis is limited and the effect of treatment is rather low. However, Bennel states that multiple trials and reviews suggest that exercise therapy might be an effective treatment strategy for hip osteoarthrosis.[17]

Below you can see a link to a summarised table with relevant studies using exercise therapy on land or in water (aquatherapy) and what they researched.

Table (from Bennell, K., “Physiotherapy management of hip osteoarthritis Journal of Physiotherapy”, Volume 59, Issue 3, September 2013, Pages 145–157.)

Exercises could be done in water as well, in order to facilitate recovery of the motorfuntion. In this situation, gravity is greatly reduced thus the burdensome weight and tension at the height of the effected joint will be reduced as well. Advice and education is important in treatment, tell the patient about their condition. Why does it occur? What's the treatment? What's the importance of exercise? This will make the patient have a clear understanding in his condition and will improve the healing process.However, it is unclear if aquatic exercises are more effective than exercises on land. There is also no clear evidence on balneotherapy. Currently, there doesn’t exist evidence that balneotherapy might be a beneficial therapy approach.[17][23][24][25]

Ultrasound therapy has been used across the globe in clinical practice, but as there is little evidence surrounding its use in the management of hip osteoarthritis, it is not recommended to use.[17]

Manual Therapy[edit | edit source]

A range of manual therapies is used as manual therapy treatment. These therapies are:[17]

- soft tissue techniques and stretches

- mobilisation of accessory and physiological movements

- manipulation/ mobilisation

The immediate effect of a mobilization intervention on elderly patients with osteoarthritis has been researched by Beselga et al (2016), they found that after an intervention pain decreased and that the range of motion in the hip joint improved. The study suggests that mobilization might reduce pain, might ‘provide a stretching effect on the joint capsules and muscles, thus restoring normal arthrokinematics or may induce pain inhibition and improved motor control’ and might reduce kinesiophobia.[25] However, these effects are currently not proven as studies regarding long-term effects are lacking. Further research for these effects is needed.[25]

“While there have been no reports of serious adverse events associated with the use of manual therapy in patients with hip osteoarthritis, therapists should advise patients about the possibility of self-limiting posttreatment soreness.”[17]

Resources[edit | edit source]

http://www.guidelines.gov/content.aspx?id=36893

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed?otool=vublib

http://apps.webofknowledge.com.ezproxy.vub.ac.be:2048/WOS_GeneralSearch_input.do?product=WOS&search_mode=GeneralSearch&SID=U2HYlXJGBQdVzdFFDhX&preferencesSave d=

https://scholar.google.be/?inst=vub.ac.be

Clinical Bottom Line[edit | edit source]

Depending on the severity of the condition, managment will vary from patient to patient. It is important that the clinician individualizes treatment to each of their patients in order to ensure optimal outcomes.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 Murphy NJ, Eyles JP, Hunter DJ. Hip osteoarthritis: etiopathogenesis and implications for management. Advances in therapy 2016;33(11):1921-46.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Cooper C, Javaid MK, Arden N. Epidemiology of osteoarthritis. In: Atlas of Osteoarthritis. Tarporley: Springer Healthcare, 2014. p22.

- ↑ Cross M, Smith E, Hoy, Nolte S, Ackerman I, Fransen M, Bridgett L, Williams S, Guillemin F, Hill CL, Laslett LL, Jones G, Cicuttini F, Osborne R, Vos T, Buchbinder R, Woolf A, March L. The global burden of hip and knee osteoarthritis: estimates from the Global Burden of Disease 2010 study. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 2014;73:1323-1330.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Nüesch E, Dieppe P, Reichenbach S, Williams S, Iff S, Jüni P. All cause and disease specific mortality in patients with knee or hip osteoarthritis: population based cohort study. Bmj 2011;342:1165.

- ↑ Cimmino MA, Sarzi-Puttini P, Scarpa R, Caporali R, Parazzini F, Zaninelli A, Marcolongo R. Clinical presentation of osteoarthritis in general practice: determinants of pain in Italian patients in the AMICA study. Seminars in arthritis and rheumatism 2005;35(1):17-23).

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Ganz R, Leunig M, Leunig-Ganz K, Harris WH. The etiology of osteoarthritis of the hip. Clinical orthopaedics and related research 2008;466(2):264-72.

- ↑ Harris WH. Etiology of osteoarthritis of the hip. Clinical orthopaedics and related research 1986; 213:20-33.

- ↑ Hoaglund FT, Steinbach LS. Primary osteoarthritis of the hip: etiology and epidemiology. Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons 2001;9(5):320-7.

- ↑ Reginister J-Y, Pelletier J-P, Martel-Pelletier J, Henrotin Y, editors. Osteoarthritis: Clinical and Experimental Aspects. Berlin: Springer, 1999.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Diseases and conditions: Osteoarthritis of the hip.https://orthoinfo.aaos.org/en/diseases--conditions/osteoarthritis-of-the-hip (accessed 14/07/2018).

- ↑ Crielaard JM, Dequeker J, Famaey JP, Franchimong P, Gritten CH., Huaux JP. Osteoartrose. Brussels: Drukkerij Lichtert, 1985.

- ↑ Walters J, editor. Orthopaedics - A guide for practitioners. 4th Edition. Cape Town: University of Cape Town, 2010.

- ↑ Kim C, Nevitt MC, Niu J, Clancy MM, Lane NE, Link TM et al. Association of Hip Pain with Radiographic Evidence of Hip Osteoarthritis: Diagnostic Test Study. BMJ. 2015 Dec 2;351:h5983.

- ↑ Fernandez M, Wall P, O’Donnell J, Griffin D. Hip pain in young adults. Aust Fam Physician. 2014;43(4):205–9.

- ↑ Physiotutors. Cluster of Sutlive | Hip Osteoarthritis Diagnostic Cluster. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8xrDWgIUMO4

- ↑ Brandt CD. Diagnosis and non-surgical management of osteoarthritis. USA: Professional Communications, Inc. 2010.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 17.5 17.6 17.7 17.8 Bennell K. Physiotherapy management of hip osteoarthritis. J Physiother. 2013; 59(3):145–157.

- ↑ CRIELAND, e.a., Osteoartrose, Lichtert, Brussel, 1985

- ↑ Bennell KL, Egerton T, Pua YH, Abbott JH, Sims K, Metcalf B et al. Efficacy of a multimodal physiotherapy treatment program for hip osteoarthritis: a randomised placebo-controlled trial protocol. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2010;11:238.

- ↑ Pisters MF, Veenhof C, Schellevis FG, De Bakker DH, Dekker J. Long-term effectiveness of exercise therapy in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee: a randomized controlled trial comparing two different physical therapy interventions. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2010;18(8):1019-26.

- ↑ Veenhof C, Köke AJ, Dekker J, Oostendorp RA, Bijlsma JW, van Tulder MW et al. Effectiveness of behavioral graded activity in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip and/or knee: A randomized clinical trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;55(6):925-34.

- ↑ Sutlive TG, Lopez HP, Schnitker DE, Yawn SE, Halle RJ, Mansfield LT et al. Development of a Clinical Prediction Rule for Diagnosing Hip Osteoarthritis in Individuals With Unilateral Hip Pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2008;38(9):542-50.

- ↑ Wright A, O'Hearn MA. Differential diagnosis and early management of rapidly progressing hip pain in a 59-year-old male. J Man Manip Ther. 2012;20(2):96-101.

- ↑ Verhagen AP, Cardoso JR, Bierma-Zeinstra SM. Aquatic exercise & balneotherapy in musculoskeletal conditions. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2012;26(3):335-43.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 Beselga C, Neto F, Alburquerque-Sendín F, Hall T, Oliveira-Campelo N. Immediate effects of hip mobilization with movement in patients with hip osteoarthritis: A randomised controlled trial. Man Ther. 2016;22:80-5.