Tibial Spine Fracture and Physical Therapy Protocol

Original Editor - Ruchi Desai

Top Contributors - Ruchi Desai, Kim Jackson and Lucinda hampton

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

The lower leg is made up of two bones: the tibia and fibula. The tibia is the larger of the two bones. It supports most of your weight and is an essential part of both the knee joint and ankle joint. The tibial spine is a specialized ridge of bone in the tibia where the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) attaches. This ligament is integral maintaining flexibility and stability in the knee.

Tibial spine fracture (also called Tibial Eminence Fracture) is a break at the top of the tibia bone in the lower leg near the knee as a result of high amounts of tension placed upon the Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL). This type of injury is most common in

1) children ages 8 to 14 years of age[1].[2]

2) The incidence of these fractures is higher among adolescent girls due to their inherent skeletal immaturity.

3) It has also been proposed that injury occurs secondary to greater elasticity of ligaments in young people.

4) It can occur during a sporting event or direct trauma with a hyperextension injury causes an avulsion fracture occurring at the tibial eminence while the ACL is spared.

Mechanism of Injury / Pathological Process[edit | edit source]

Tibial spine fractures are typically caused by the stress from a high-intensity activity, a hard impact to the bone, or from an already compromised or weakened bone. Usually younger people will get a tibial spine fracture from a hard impact injury, such as a fall from a height or a sports-related injury. Older people tend to get a tibial spine fracture from weaker bones or a small injury.

This type of force causes the ACL to pull on the tibial spine. Because the bones of children this age still have open growth plates, the ACL is stronger than the tibial spine and can pull away from the bone (avulse), causing a Fracture.

Classification and Management for Tibial spine fracture[edit | edit source]

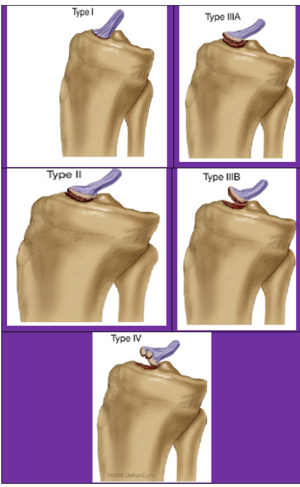

Under the Meyers and McKeever system (with modifications by Zaricznyj) injuries are classified into four main types[3][4]:

- Type I is the minimal displacement of an avulsed fragment: This injury is treated conservatively by closed reduction, where the tibia is set into place without a surgical incision. and then the knee is immobilized in a long-leg cast or a fracture brace set at 10 to 20 degrees of knee flexion. Fixed flexion is recommended due to the fact that full extension may place excessive tension on the ACL and popliteal artery. Immobilization is then recommended for approximately 6 weeks depending on the patient's age, healing rate, and radiological findings.

- Type II classification is the displacement of half of the anterior third of the ACL insertion causing a posterior hinge: In most cases, closed reduction and immobilization may be attempted after aspirating knee haemarthrosis. Knee extension allows femoral condyles to reduce the displaced fragment. If acceptable reduction is achieved conservative management should be continued. If there is persistent superior displacement of the fragment seen in the x-ray then it is preferable to do arthroscopic reduction and internal fixation because chances for soft tissue entrapment at the fracture site are high.

- Type III is the complete separation of the avulsion site:

- Type IV was later added by Zariczynj to include comminuted fractures of the tibial spine: Type III & Type IV Treatment of displaced tibial spine avulsion fractures has evolved over a period of time from conservative management to open reduction and internal fixation to arthroscopic reduction and internal fixation. Various methods of fixation are used in the operative treatment of these fractures varying from retrograde wires /screws, antegrade screws, sutures, suture anchors, and a recently described suture bridge and K wire and tension band wiring technique.

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

- Swelling

- Inability to weight bear

- Bruising

- Reduced knee range of movement (ROM)

- History of trauma

- Pain

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

ACL tear, meniscal tear, LCL or MCL sprain, patella fracture, osteochondral fragment, femoral condyle fracture, tibial plateau fracture.

Differential diagnosis can be ruled in or out by obtaining radiographs of the knee and using further diagnostic imaging such as CT or MRI to assist in the diagnosis.

Diagnostic Procedures & Imaging[edit | edit source]

Standard imaging for tibial spine fractures include anteroposterior(AP) and lateral radiographs. Lateral radiographs should be true lateral radiographs which are particularly useful to assess degree of displacement and type of fracture. CT scan is useful in better assessment of fracture anatomy and degree of communition . MRI is useful in outlining the non-osseous concomitant injuries like meniscal injury, cartilage injury and other ligamentous injury[5]. along with this on physical examination with special test for knee joint doctor will rule out other knee conditions.

Management / Post-Operative Rehabilitation[edit | edit source]

Tibial eminence fractures have excellent prognosis. Previously, prolonged immobilization may lead to arthrofibrosis and a permanent loss of full extension. Therefore, earlier rehabilitation is crucial as it encourages a faster recovery and prevents the development of secondary complications. Rehabilitation is similar to ACL tear protocols and which has been described in below table[6][3].

| Goals | Brace | Weight Bearing | ROM | Exercises | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase -I

(0-6 Weeks) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Phase II: (Weeks 7-12) |

|

|

|

| |

| Phase III: (Weeks 13-18) |

| ||||

| Phase IV: (Months 5-6 )- Return to Sport |

|

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ GronkvistHFracture of the anterior tibial spine in children. J Pediatr Orthop, 19844465468

- ↑ eyersM. HMckeeverF. MFracture of the intercondylar eminence of the tibia. J Bone Joint Surg Am 19705216771683

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Salehoun, Roya, and Nima Pardisnia. “Rehabilitation of tibial eminence fracture.” The Journal of the Canadian Chiropractic Association vol. 51,2 (2007): 99-105.

- ↑ https://jposna.org/index.php/jposna/article/download/68/68

- ↑ https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/43257

- ↑ https://www.slu.edu/medicine/orthopaedic-surgery/sports-medicine/_pdfs/tibial-spine-repair.pdf