Self-management Techniques to Enhance Physical Activity

Original Editor - Justin Louie, Stuart Maytham, Dawn Williams, Paul Reen, Janelle Eisler Carr, Ciara Wright as part of the QMU Current and Emerging Roles in Physiotherapy Practice Project

Top Contributors - Justin Louie, Ciara Wright, Stuart Maytham, Kim Jackson, Paul Reen, Evan Thomas, 127.0.0.1, Admin, Scott Buxton and Rucha Gadgil

Introduction[edit | edit source]

The World Health Organization (WHO) has identified “physical inactivity” as a global epidemic, with the region of the Americas having the highest prevalence of inactivity followed by the Eastern Mediterranean Region [1]. The cost of physical inactivity on the health care system is staggering. In the United Kingdom, the cost is estimated to be approximately £8.2 billion [2], whilst in Canada, the cost is approximately $6.8 billion (£3.76 billion) per year [3]. The United States of America spends more than 75% of the $2 trillion (£1.3 trillion) annual health care budget on physical inactivity related hospitalizations. [4].

|

|

Physical inactivity is the fourth leading risk factor for global mortality, contributing to approximately 3.2 million deaths annually worldwide[1] . More than 50 years of statistical research confirms the relationship between physical activity and mortality[6], with reports suggesting that at least 80% of premature CVD and 40% of cancer deaths could have been prevented through regular physical activity[1].

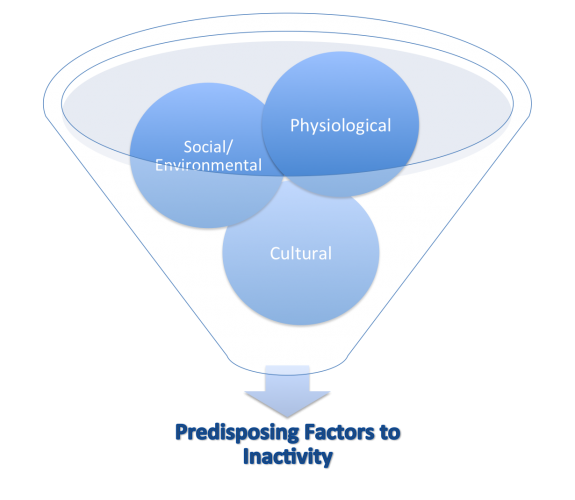

Why is the General Population so Inactive?[edit | edit source]

Social[edit | edit source]

According to the WHO, there are several reasons for the worldwide physical inactivity epidemic in the regions of the Americas, including increased workplace and leisure-time sedentary behaviour. The increased sedentary lifestyle has been shown to predispose individuals to pain, disabling conditions, and musculoskeletal complaints. In the workplace, this may lead to injury, varying degrees of disability, absenteeism, reduced overall job performance, or other undesirable outcomes[7]. These consequences of physical inactivity may contribute to absence due to sickness in the UK, which accounts for 3–4% of average working time and costs employers £9 billion each year and a further £20 billion to the UK economy (Chartered Institute of Personal Development, 2010).

Environmental[edit | edit source]

Also, the increase in urbanization has led to several environmental factors that discourage physical activity. These factors include increased traffic, increased pollution, and decreased access to parks and recreation facilities[1].

Cultural[edit | edit source]

As a society with a growing health epidemic, it appears that individuals with lower perceived self-efficacy increasingly seek immediate reward over healthier choices with long-term benefits

Physiological[edit | edit source]

Malnutrition, poor sleep, higher stress, lower self-efficacy = lower energy and motivation

Is There a Solution?[edit | edit source]

In order to combat this growing epidemic at a global level, the WHO has developed the Global Recommendations on Physical Activity for Health guidelines. The Global Recommendations on Physical Activity for Health guidelines help educate people regarding the minimum amount of physical activity required to receive the benefit of a decreased risk of NCD[1] . There are three age categories, which are grouped according to the relevant scientific evidence regarding the prevention of NCD through physical activity[1]. The age groups are as follows: 5–17 years old, 18–64 years old, and 65 years old and above.

Several countries have adapted the Global Recommendations on Physical Activity for Health guidelines.

The Canadian Physical Activity Guidelines[9]

The United Kingdom Physical Activity Guidelines [10]

The United States of America Physical Activity Guidelines[11]

These physical activity guidelines can assist physiotherapists in their treatment of NCD conditions related to physical inactivity through education and promotion of physical activity self-management. It appears that traditional treatment strategies, such as diet, exercise, pharmacology, and behavioural therapy, are not consistently effective [12]. The Department of Health (2012)[13] are encouraging the use of “self-management” techniques to promote long-term behaviour change with the aim to reduce cost. The goal is that people will feel “empowered” and “independent,” thus requiring less involvement with the health care service.

What is Behaviour?[edit | edit source]

Behaviour is the range of actions and mannerisms made by individuals, organisms, systems, or artificial entities in conjunction with themselves or their environment.[14] It is the response of the system or organism to various stimuli or inputs, whether:

| Internal | External |

|---|---|

| Being worried about your health and/or appearance | going to the gym [15] |

| Conscious | Subconscious |

|---|---|

| Deciding you should go for a walk | associating exercise with fun and reward[15] |

| Overt | Covert |

|---|---|

| Going out for a run | lying about exercise[15] |

| Voluntary | Involuntary |

|---|---|

| Deciding you should go for a walk | missing the bus and having to walk[15] |

Learning Behaviours[edit | edit source]

Learning is the act of acquiring new, or modifying and reinforcing, existing knowledge, behaviours, skills, values, or preferences and may involve synthesizing different types of information.

- Non-associative learning refers to a relatively permanent change in the strength of response to a single stimulus due to repeated exposure to that stimulus.

- Habituation is a form of learning in which an organism decreases or ceases to respond to a stimulus after repeated presentations. E.g. feeling nervous/excited when you begin exercising but after a while you are unfazed by going.

- Sensitisation is an example of non-associative learning in which the progressive amplification of a response follows repeated administrations of a stimulus. E.g. increased sensitivity due to a history of chronic pain when attempting to exercise.

- Associative learning is the process by which an association between two stimuli or a behaviour and a stimulus is learned.

- Operant conditioning - The use of consequences to modify the occurrence and form of behaviour[16]

- Classical conditioning - Involves repeatedly pairing an unconditioned stimulus (which unfailingly evokes a reflexive response) with another previously neutral stimulus (which does not normally evoke the response). Following conditioning, the response occurs both to the unconditioned stimulus and to the other, unrelated stimulus (now referred to as the "conditioned stimulus"[16]

Theories and Models of Behaviour Change[edit | edit source]

Behavioural change theories are attempts to explain why behaviours change. These theories cite environmental, personal, and behavioural characteristics as the major factors in behavioural determination.

Each behavioural change theory or model focuses on different factors in attempting to explain behavioural change.

- Theory of reasoned action A model for the prediction of behavioural intention, spanning predictions of attitude and predictions of behaviour. The subsequent separation of behavioural intention from behaviour allows for explanation of limiting factors on attitudinal influence [17]

- Social cognition theory Holds that portions of an individual's knowledge acquisition can be directly related to observing others within the context of social interactions, experiences, and outside media influences[18]

- Theory of planned behaviour states that attitude toward behaviour, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control, together shape an individual's behavioural intentions and behaviours [17].

- Transtheoretical model Assesses an individual's readiness to act on a new healthier behaviour, and provides strategies, or processes of change to guide the individual through the stages of change to Action and Maintenance[19]

- Health action process approach Refers to a replacement of health-compromising behaviours (such as sedentary behaviour) by health-enhancing behaviours (such as physical exercise)[20]

- B=MAT Model Shows that three elements must converge at the same moment for a behaviour to occur: Motivation, Ability, and Trigger. When a behaviour does not occur, at least one of those three elements is missing[21]

Self-Efficacy[edit | edit source]

Self-efficacy is an important factor in all the theories outlined above and is defined by Bandura as the extent or strength of one's belief in one's own ability to complete tasks and reach goals i.e. the more that we believe that we can achieve a goal the more likely we will be to do so.[22]

Self-efficacy affects every area of human endeavour. By determining the beliefs a person holds regarding his or her power to affect situations, it strongly influences both the power a person actually has to face challenges competently and the choices a person is most likely to make. These effects are particularly apparent, and compelling, with regard to behaviours affecting health [23].

Habits[edit | edit source]

A habit is a routine of behaviour that is repeated regularly and tends to occur unconsciously.

The process by which new behaviours become automatic is habit formation. Old habits are hard to break and new habits are hard to form because the behavioural patterns we repeat are imprinted in our neural pathways, but it is possible to form new habits through repetition.

Health Behaviour Change[edit | edit source]

Actions to bring about behaviour change may be delivered at individual, household, community or population levels using a variety of means or techniques. Significant events or transition points in people's lives present an important opportunity for intervening at some or all of the levels because it is then that people often review their own behaviour and contact services.

The health-promoting health service approach has developed the concept that ‘Every healthcare contact is a health improvement opportunity’. This is reinforced in the National Delivery Plan for the Allied Health Professions [AHPs] in Scotland, 2012-2015. However, it could strongly be argued that Physiotherapists don’t have adequate resources or training to tackle health behaviour change effectively [24].

Self-Management[edit | edit source]

Self-management is a model of care in which patients are encouraged to use strategies and learn skills to manage their own health needs [25]. Patients are active participants and take responsibility for their own health care behaviours, a notion that is lost in the medical model and passive therapies [26]. Recently, the WHO defined self- management as:

“the ability of individuals, families and communities to promote health, prevent disease, and maintain health…..to cope with illness and disability with or without the support of a health-care provider.”[1]

The Scottish Government has dedicated £6 million over the past three years to the Long Term Conditions Alliance Scotland in their promotion of self-management. The document “Gaun Yersel” was developed in alliance with patients and outlines the responsibilities and commitments of the government in combination with their 2020 Vision whereby individuals and communities aim to achieve social change.

Swan 2012 highlights the paradigm shift in health care from the concept that the patient’s health is the responsibility of the health care professional to ‘My health is my responsibility, and I have the tools to manage it’ [27]. The NHS must continue to make the transition from a ‘sickness’ service to a ‘well-being’ service.

Lorig et al (2003)[28]. explain that “wellness” from self-management requires attention in three key domains: the medical, behavioural, and emotional elements of a person’s life. They recognise that physiotherapists do not have extensive training in each domain, but they stress that physiotherapists’ expertise in exercise therapy, pain management, and healthy lifestyles promotion enables the profession to play a key role in supported self-management.

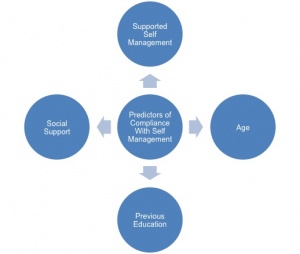

Predictors of Self Management Compliance[edit | edit source]

Concerns have been raised over the effectiveness of self-management and its ability to reduce pain and disability, or increase inactivity. Crowe (2010)[29] echoes the point that, despite the current emphasis on self-management, there is minimal evidence to suggest which strategies are actually effective. It has been argued that long-term behavioural change is difficult to sustain without the input of a health care professional [30]. Oliveira discovered that many studies did not conform to a self-management definition, and there are varying approaches being used to promote self-management by health care professionals. The Chartered Society of Physiotherapy recently estimated that 50% of patients suffering a chronic condition ignore professional healthcare advice (2014); therefore, it is important to consider the patient’s expectations of self-management and the support they receive from their health care professional (HCP) [31]. Undoubtedly, self-management will be more effective with some patients than others. It is important to recognise that further research is required to determine which aspects of self-management are beneficial or non-beneficial, as well as how HCPs should encourage and promote its use to best effect.

A recent study (Kawi, 2014)[32] concluded that self-management may be effective for certain patient groups only, suggesting that indicators for compliance need to be established to recognise potential responders. The main predictors of compliance with self-management were:

- Age (generally, the younger the patient the higher the participation in self-management)

- Supported self-management (SSM) (the greater the amount of SSM available the higher the level of continued SM)*Previous education

- Better overall health

- Support received from family and friends increases compliance and motivation.

A key component for the success of self-management appears to be the level of support a patient receives from an appropriate HCP, such as a physiotherapist. The Cooper et al (2009)[33] paper identified that patients want direct access to their physiotherapist for follow-up advice and reassurance. This could take the form of a review visit, telephone call, or even an email. SSM is a vital component that cannot be ignored in the quest for cost reduction. Further research is required to better understand this relatively new approach to patient management. The core components of SSM need to be established, and support into the mental well-being of a patient is essential when delivering a biopsychosocial approach to SSM.

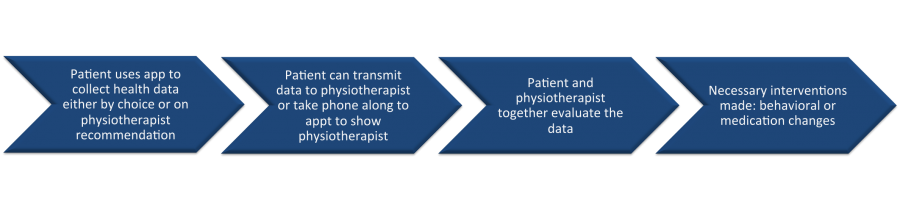

The Internet is increasingly being used to provide interventions, information, and guidance on health-related behaviour change. A recent survey reported that of the 74% of American adults who use the Internet, 80% have used it to find health information. Social networks in health and other types of social media provide people with new opportunities to share health information easily. With the prediction that 3 out of 4 mobile phone users in the UK will own a smartphone by 2016, it is important to recognise that the use of smartphone apps in conjunction with physiotherapy support may be used as a self-management tool to promote and enhance behaviour change.

Approaches[edit | edit source]

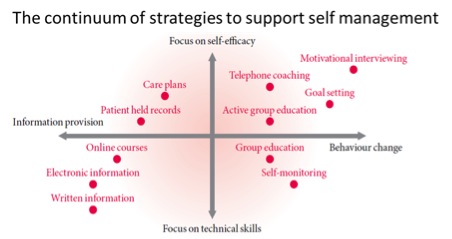

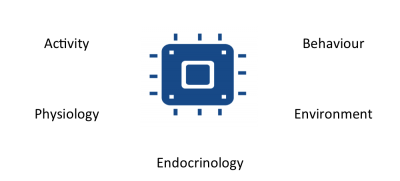

According to Phillips (2012) [34], a person needs to learn a range of skills to manage the biological, mental, emotional, and social impacts of their condition, including the effects of physical inactivity on health. This is termed the “biopsychosocial approach.” The following diagram depicts the range of strategies available to support the use of self-management:

|

Figure 1: The Health Foundation Evidence: Helping People Help Themselves, May 2011[35] |

Motivational Interviewing[edit | edit source]

Once a person has accepted that he or she has a lifestyle problem, a key element of self-management is the motivation to change behaviour. It is important to note that, if people are in denial about their inactivity levels, it will have a detrimental impact on their engagement with self-management treatment options [36].

Motivational interviewing can be used by therapists in a person-centered collaboration with the patient which addresses the person’s fears, anxieties or ambivalence towards change, helping to weigh the “pros and cons” of change [37]. The Motivational Interviewing Network of Trainers encourages the use of exploring a person’s need to change in an “atmosphere of acceptance and compassion [38].

|

|

The British Medical Journal (BMJ) (2010) accept that patients often appear unmotivated towards changing lifestyle habits and suggest clinicians need to alter their approach from the traditional directed style as this leads to resistance and passivity from the patient. The BMJ suggest the use of a “guiding” style when goal planning using 3 core skills - Asking, Listening and Informing. The BMJ has developed a Top 10 list of useful questions to consider when delivering a motivational interview:-

- What changes would you most like to talk about?

- What have you noticed about...?

- How important is it for you to change...?

- How confident do you feel about changing...?

- How do you see the benefits of...?

- How do you see the drawback of...?

- What will make the most sense to you?

- How might things be different if you...?

- In what way?...

- Where does this leave you now? [39]

The supported self-management approach is a collaboration between the physiotherapist and the individual in which the physiotherapist assists the person to make educated and informed decisions about their own goals and expectations for the future [40].

Goal Setting[edit | edit source]

There is much evidence available for the use of goal setting when attempting to change behaviours. One popular model of goal setting is SMART. Harding (2000)[26] suggests that patients should be encouraged, in conjunction with their therapist, to set individual and personalised goals. It is important to set targets at a manageable baseline to achieve something previously feared, which can then be recognised as an achievement.

Quantified Self[edit | edit source]

“The quantified-self movement exposes the motivational effect on health behavioural change of quantitative measurement and analysis of personal health parameters. “ [42]. Technologies have become increasingly popular within the general population as self-tracking strategies, while health care professionals are eager to embrace the opportunities they perceive through using what has been dubbed ‘mhealth’ to promote the public’s health [43]. This electronic monitoring of human health behaviour is fast becoming an area of increasing research with a focus on ‘sensor fusion’ using single systems or devices [44].

Utilising wearable systems for continuous monitoring is the keystone of the Quantified Self movement which aims to give a more accurate measure of human motion during day-to-day life [45]. These innovations are emerging for managing healthcare to revolutionize involvement of the healthcare professional and could increase the autonomy and patient involvement in terms of their health [46] and hold the potential to significantly benefit society [45]. A recent article in the Telegraph by the Health Minister Dr Dan Poulter discusses how technology is driving improvement in personalised healthcare. A recent study by Vuori and colleagues (2013) remarked that the attitudes of physiotherapists for advising physical activity were amongst the most positive, and we have a key role to play in aiding behavior change to promote healthier lifestyles[47]. As well as facilitating physiotherapists to take on the role as a lifestyle coach, these technologies can aid with monitoring chronically ill patients to reduce re-hospitalisation [48]. Appelboom and colleagues (2014c)[49] refers to it as ‘Quantifying self hybrid models’ which essentially combine patient-reported outcomes and telemonitoring, i.e. integration of passive data collection and patients actively reporting, to reduce the subjective unreliance. Lupton (2013b) refers to it as ‘digitized health promotion’ and that these digital health technologies are advocated for drawing a renewed focus on personal responsibility for health [50].

|

‘What gets measured gets managed’ – Peter Drucker – Management Consultant and Presidential Medal of Freedom, 2002. [51] |

In line with the behaviour change models, once the patient adopts the appropriate technologies to engage in self-monitoring and self-care health can become more self-manageable [50]. However, survey research has reported that many health professionals are not themselves using mhealth in their professional practice to any great extent as yet, due to lack of knowledge about how best to do so or concern about having to learn about using new technologies [52]. This may be because little or no information is available to substantiate the validity of these consumer-based activity monitors. Thus it is important to evaluate these devices so individuals and us as physiotherapists can make informed decisions [53].

What Devices Does Quantified Self Consist Of?[edit | edit source]

- Sensor - Each quantified self technologies have a sensor to pick up whatever it is they are measuring

- Wireless - Quantified self technologies are able to sync wirelessly with other technologies such as smartphones and laptops

- Cloud storage - The data collected from these technologies may be stored in vast quantities online

- Mobile - Mobiles play a key role as they are able to both collect data and sync with other technologies to then store the data online

- Apis - API is an electronic data interface system which allows numerous technologies to interact and share data by speaking the same ‘language’

- Externals - Scales may now be purchased which wirelessly sync to your laptop

- Wearables - Numerous wearable bracelets tracking activity levels and sleep are available on the market as outlined above.

- Biosensors - Biosensor tattoo are now available which can monitor your hormone levels.

Current Tools Available[edit | edit source]

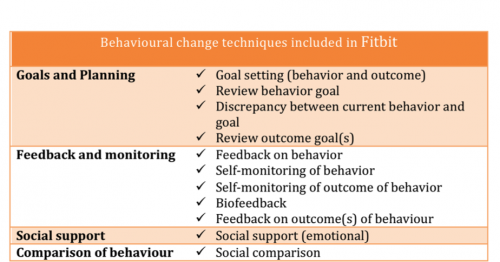

Peter Drucker (2002) highlights that attempts are being made to standardize the mhealth data, with the idea being that with a basic set of guidelines these wearable technologies information can inform healthcare[51]. Self-tracking encourages individuals to think about their activity levels in the hopes of changing their behaviour (Lupton 2013) and physiotherapists play a key role in guiding behaviour change for healthy living [50]. Lyons and colleagues (2014) provide a very comprehensive guide of behaviour change techniques associated with physical activity change implemented in self-tracking devices. In this recent analysis of these devices, it was found that the most common techniques employed as part of the system, were self-monitoring of behaviour, feedback, behavioural goal-setting and highlighting discrepancies between current and goal behaviour [54].

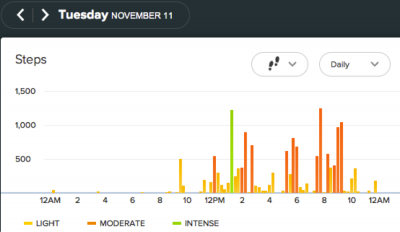

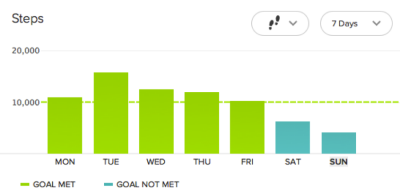

The Fitbit one is a triaxial, accelerometry-based device that can measure steps taken, floors climbed, distance travelled, calories burned, and sleep quality. The device has many advantages which include, being a small, compact, lightweight, easy-to-use device with a 5-10 day battery life and an internal memory store of up to 23 days [53]. The device also boasts a wireless function whereby data can be automatically synced to a computer or the app for quick analysis and tracking purposes. The figures below show examples of a 7 day fitbit dashboard view and a daily view of step count [55].

Some activity monitors do not measure slower walking speeds accurately [56]. However as determined by Ryan et al. (2006)[57] the activPAL’s accuracy is not influenced by walking speed and similarly, Takacs et al. (2013) aimed to determine the validity and reliability of the Fitbit one in a population of healthy individuals at different walking speeds, as patients with neurological or musculoskeletal impairment may walk at slower speeds than healthy individuals [55]. An inaccurate measure of activity level may have an adverse effect on health status and adherence to an exercise programme. The research findings showed that the fitbit output count and the observer count at the varying speeds were matched and the inter-device reliability was high at all walking speeds with percent relative error being less than 3%. These results show promise for the use of fitbit one in measuring physical activity in people with walking impairment.

Recently, Lee and colleagues (2014) examined the validity of energy expenditure estimates from a number of consumer-based physical activity monitors under free-living conditions [53]. Fitbit (One and Zip) were included within the study as were the Jawbone Up, bodyMedia FIT armband, directLife monitor, ActiGraph, and Basis B1 Band monitor. The correlation coefficients were investigated for these monitors, with significant findings for the Fitbit monitors, showing a strong relationship between both indirect calorimetry (Fitbit one r = .81 and Fitbit zip r = .81) and also between the Fitbits and bodymedia FIT armband (r = 0.90). Conclusion of the research showed promising preliminary findings for the Fitbit, the Zip in particular. However, it is also important to note that all of the devices used in the study show decent potential as their results were as good as, if not greater than the Actigraph.

Lyons et al. (2014) recently conducted an analysis of activity monitors as behavior change tools, one of the included tools was the Fitbit and it was found to be one of the activity monitors which encompasses a good range of behavior change techniques (see figure 2)[54]. As physiotherapists setting SMART goals with our patients is important for effective interventions. Tudor-Locke et al. (2011) noted that the default activity goals for some of these monitors may be inappropriate for individuals with disabilities or chronic conditions, older adults or children and thus it is our responsibility to set realistic short and long term goals for our patients with the help of these activity monitors to observe their progress[58].

[54]

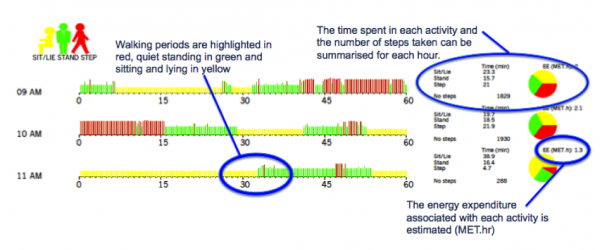

A device showing promise within physical activity research is PAL technologies activPAL motion sensor and accelerometer. It provides a way of quantifying free-living sedentary, upright and ambulatory activities (PALtechnologies 2014). This company who recently hosted a stand at the Student Physiotherapy Conference Scotland (SPCS) 2014 in Queen Margaret University, has featured in more than 500 peer-reviewed publications. This year to date, the activPAL has been used in 50+ research articles in looking at validation studies, along with interventions involving physical activity and sedentary behaviour in various patient populations including stroke, older adults, overweight/obese, adolescents, Parkinson’s Disease, cerebral palsy for example. The device is designed to be worn on the mid-thigh and is a very small and lightweight electronic device that can sense three classes of activity, sitting/lying, standing and stepping second by second [59]. The activPAL is capable of recording for in excess of seven days continuously and this stored activity profile can be retrieved and processed using a computer. The data is presented in the forms of a daily time graph of monitored activity, as can be seen in figure 3. There is also a detailed explanation of the layout of the activity profile on Pal Technologies website

Available Evidence[edit | edit source]

The publication of Dowd et al. (2012) found strong support for the criterion and concurrent validity of the tool for measuring both physical activity and sedentary behaviours in adolescent females [61]. A strong and positive relationship (r=0.96, p<0.01) between the count function of the activPAL and that of the Actigraph was established. This journal showed promise of this device within a key population of low activity levels whilst also highlighting support for the device to accurately distinguish between the 3 classes of activity. Similarly, Bassett et al. (2014) validated the ActivPAL’s detection of positional changes using direct observation as the validation criterion, finding that excellent agreement existed between the two methods for lying down (correctly classified 100% of the time), standing/light activity (90.8%), and stepping (100%)[62]. Aphrodite et al. (2009) undertook research to provide evidence for the validity and reliability of the activPAL within a health promotion context to use it to identify differences in daily activity levels of physiotherapists and non-health related professionals. Initially, in evaluating validity and test-retest reliability, the activPAL gave almost identical measures with the true values and the measures obtained showed little variation within the fifteen recordings of the set repeated activities. The resulting findings show promise in measuring physical activity levels in healthy individuals and also added knowledge to the levels of activity engage by physiotherapists in comparison to non-health related professionals [59].

Is It Valid and Reliable in Various Populations?[edit | edit source]

Davies et al. (2012) showed acceptable validity, practical utility and reliability in pre-school children, measuring posture and normal activities [63]. The central tendency measures used were the median for sensitivity to measure sit and lie with a value of 92.8% (interquartile range 76.1%-97.4%) and positive predictive value of 97% (91.5%- 99.1%). These results further add to the support for its usefulness in a young population, while also reflecting similar results found in an adult population by Grant et al. (2006) [64]. The inter-device reliability was found to be 0.79 for walking and the sit-to-stand transition analysis was found to be identical between the observer and the activPAL monitor for all tests conducted [64]. O’Donoghue and Kennedy (2014) found promising support for the use of the activPAL amongst people with cerebral palsy, as for these individuals the noted larger variability in gait and increased postural sway in standing may have impacted on the reliability of the monitor to accurately measure activity [65]. However, perfect agreement for transitions and high agreement for sitting (mean differences -1.8 and -1.8s), standing (0.8 and 0.1s), walking (1 and 1.1s), with a lower agreement for step count (4.1 and 2.8 steps) were found. It was highlighted here that the discrepancies in step count may be due to methodological difference, the activPAL measures steps taken by the leg it is worn on and not total steps taken compared to observers, perhaps underestimating step count for this population, particularly if worn on the affected leg. However, the results of the study suggest that a good level of agreement exists between activPAL and direct observation for this population and should be replicated in free-living environments to fully determine its usefulness for this population and to allow for clinical decisions to be made.

Benefits of Self-Tracking Devices for Patients[edit | edit source]

Fritz and colleagues (2014)[66] believe this technology has the ability to persuade and motivate people and undertook a study to determine user’s attitudes towards long term use of activity sensing devices for fitness[66]. The authors were aware that not all people who purchase devices such as, Nike fuelband and fitbit etc use them long term, however, the aim of the study was to interact with people who have incorporated these devices into their daily routine with the view to understanding long term effects these devices may have [66]. According to Schull et al (2014) this long term monitoring is at the heart of the quantified-self movement as it can give an accurate understanding of human motion realities, which cannot be achieved during laboratory testing [45].

What Type of Data Can We Collect?[edit | edit source]

Big Data (future benefits to the NHS) vs personal data[edit | edit source]

Overall we can break this down into two categories:

Big data = aggregate information on many people to yield population insights.

For example, if the NHS were to coagulate data from a variety of people attempting to change their physical activity levels, this may help practitioners to facilitate other people’s behaviour change efforts more efficiently.

Personal data = best use is for implementing valid behaviour change modalities i.e. self-experimentation. The implementation of a smart health paradigm and then an awareness as to whether you are doing it and whether you are achieving your goals.

|

How Quantified Self Technologies Will Help Us Live More Like Our Ancestors. Daniel Pardi. 2014 [67] |

What Does This All Mean?[edit | edit source]

As we now know self-efficacy is a key underlying factor and this requires two parts:

- Effective health paradigm e.g. ancestral health (10,000 steps a day)

- Effective behaviour modification techniques e.g. quantified self-movement

Pursuing a healthy lifestyle has and always will require personal effort. However, unlike the past being healthy requires a deliberate effort, which means intelligent choices, must be made on a day to day basis. But we can’t simply hand patients a device and expect that to do the trick. In order to succeed in a sustainable long-lasting change, there must be some personal intention and value empowered by the individual into the device and tools which they use to achieve their goal.

Being in a position of authority, Physiotherapists are empowered to assist patients to attribute value and in turn, empower the devices and tools recommended to the patients and thus significantly affect behaviour change [68].

mHealth - The Future of Healthcare[edit | edit source]

Although currently dominating the market for self-tracking devices are the fitness-minded and tech-savvy individuals, it is apparent that there is increasing interest in expanding the use of outpatient monitoring as a strategy to improve healthcare delivery [49]. The drive towards this emerging technology trend for health promotion highlights the need for health professionals to embrace their use for helping patients to implement health behaviour change. They can provide a platform for the delivery of self-management interventions that are highly customisable, low-cost and easily accessible[69]. With reports on mhealth technologies being frequent within both the media and medical health literature due to the popularity of devices and related apps within the public [50]. For example, the Apple App Store alone offers over 13,000 health-related apps [70], with estimations in 2012, of 44 million downloads worldwide for these apps [71]. It is projected that by 2018, 485 million wearable devices will be sold annually (Drucker 2007). Furthermore, a 2012 survey in the US of 3,000 adults, indicated that 85% owned a mobile phone, 53% were smartphones, 19% of people surveyed downloaded an app for health management. This emphasizes the emerging growth of mobile technologies as well as the use of smartphones for health and wellness [72].

A major advantage with mhealth allows the health professional to monitor the patient during ADL’s and in a home environment. Frequently, problems faced by physiotherapists for patients with chronic diseases is measuring gains and losses in daily functioning over time, with the use of these sensor technologies for activity monitoring, it becomes possible to assess the effects of timing and dose of medication on physical functioning, addressing the level of activity gained throughout the day and maintenance of ADL’s, assess compliance with goals and instructions for exercise and skills practice and update instructions more frequently than an office visit[48]. The growth in uptake of these wearable fitness technologies provides an aid for health professionals to empower the patient in taking an active role in their health [73].

In the past industries harped on understanding consumers and measuring their behaviour — today, consumers themselves are tracking and generating enormous amounts of data.

| Why mobile technology may well define the future of healthcare... for everyone [74] |

However…[edit | edit source]

There are numerous examples in the literature illustrating the success of wearable technologies and online tools in increasing physical activity levels. However simply tracking an activity is not enough. Neither knowledge nor tracking alone immunizes you from an unhealthy lifestyle. The value of these devices crucially depends on the sophistication of the system it integrates with, which is highly dependent on the health knowledge of the system designer and the ability of that knowledge to translate through the system [75].

QS has enormous potential to help us be healthy and we’re just at the beginning stages of its ability to create meaningful change for individuals and populations.

Potential Challenges and Limitations of Technology[edit | edit source]

As addressed by Rutherford (2010), the most challenging obstacle facing the widespread application of these wearable technologies is whether the patients and health-care systems will adopt them. Patients may be resistive and uncomfortable with it due to wearability, security and a general dislike towards technological solutions[76]. Certainly there are certain populations it may appeal to most, however it is important to consider that the drive towards this method is an individualised approach and therefore will be such on a case-to-case basis.

Crawford (2006)[77] introduced the belief that healthism can control the fate of an individual, by that particular individual taking ownership and responsibility for their own health. Healthism attributes good health, to an individuals ability to direct everyday activities and thoughts to reaching an optimum goal and being able to maintain it over time [43]. In line with self-efficacy, if a patient does not have an inner belief that he/she cannot achieve a healthy lifestyle/ behavioural change, the ability of the self-tracking device as a tool to aid the change is greatly diminished and vice versa. The cost attributed to some of these self-tracking devices may be also seen as a limitation of their use, although research suggests that up to 50% of health apps are available for free download. Lupton (2013a) conveys that healthism tends to only be a priority for socially economically privileged people who have both the education and resources to do so [43].

Ho (2013) suggests that health professionals are unfamiliar with popular apps regarding their benefits and usage making it impossible for them to support patients in self- management or keep track of a patient’s progress [78]. In order to overcome this challenge, both clinicians and patients alike must become engaged in educating themselves about app availability. This can aid in overcoming the following challenge also. The fact that patients have to skim through a vast amount of apps with little guidance about which apps perform best and which apps are best suited to their situation (IMS Institute for healthcare informatics 2013). However, this challenge has started to be met already with the introduction of the NHS app library in the UK and US HealthTap have also created an app called AppRX, which allows 40,000 physicians to evaluate health and medical apps. This gives the potential user a professional recommendation prior to downloading an app (IMS Institute for healthcare informatics 2013).

Significance for Physiotherapists[edit | edit source]

In our recognition of the health service’s transition from a ‘sickness’ service to a ‘well-being’ service, physiotherapists, along with other Allied Health Professionals have been highlighted as ‘agents of change’ in helping this to occur which includes facilitating self-management and promoting healthier lifestyles [79]. Embracing these self-tracking devices and incorporating them as an aid for practice is in its infancy, however, it remains beneficial to be aware of the type of technology available that can aid to implement a behavior change in your patients. Pertola (2013) noted that an overwhelming amount of applications subscribed to QS have yet to make the leap from simply collecting data and presenting it to the individual, to using and integrating it in a way that assigns meaningful information to prompt emotional engagement and encourages user interaction to seek personal gain[80]. As in the figure below, if individuals come to you looking for advice on what device to use or if they already have a device and they need you to help make the results a meaningful awareness of mhealth can enhance your role (Institute for healthcare informatics 2013). Patients and health professionals should choose an appropriate app, together during a consultation to achieve an optimum health outcome [78]. The common ideal for these is the ‘10,000 steps’ a day [54], however these devices goals can be altered depending on the individual requirements. Setting realistic goals with your parents in the SMART format will benefit them and make quantifying themselves more understandable. If physiotherapists can encourage their patients to view their bodies through meaningful numbers via self-tracking devices, the patients may have a worthy goal to achieve a health change [43].

These mobile health tool’s will allow physiotherapists access to a readily flow of real-world information. Self-assessment of daily activity by patients own assessment can be variable and subjective, however with the addition of the use of an automatic monitoring system it can provide an objective measure for patient monitoring (Godfrey et al. 2007). As a result, physiotherapists will be able to design more clinically meaningful interventions, through minute by minute evaluation of quality of exercise for risk factor management as well as exercise compliance, while also providing feedback at home which may motivate and enhance self-management of patients[48].

Suggested ways to integrate mhealth (adapted from Kendall et al.2013):

- During a clinical appointment, the physiotherapist could find out, from there patient, if they use a health app or device.

- Learn about this app/ tracking device and familiarize yourself with the features/ benefits and limitations.

- After a few months, once you have built up a repertoire of useful information about various app’s/ device start to recommend app’s/devices to patients currently not using app’s /devices. Make sure the app chosen is specific to the needs of that individual.

- Find outpatients attitudes towards the app after continued use- May potentially choose to evaluate the data from their app/device during an appointment.

- Engage in interaction with other physiotherapists regarding app’s they recommend to patients etc.

- Review apps with other physiotherapists to ensure they are safe, accurate and appropriate for patients.

- Become an active user of technology to monitor/manage your own health- ‘Practice what you preach’.

Conclusion[edit | edit source]

Modern humans have inherited a genome programmed for movement from a time when physical activity was obligatory for survival. Inactivity sets off a chain of molecular mechanisms that affect the way our cells communicate, which leads to disease including NMSK disorders. [82]

With the quantified self/wearable technology market growing momentum, the extremely low levels of physical activity and with the lack of resources available to Physiotherapists to assist with real tangible behaviour change; this is a hugely relevant area of potential research.

Recently there has been a growing focus on preventative approaches towards increasing levels of chronic disease. Physiotherapists are considered to be in an ideal position to help with this mission during their consultations, however little training and/or resources are provided to enable them to do this in an effective way [83].

Current literature states that there is a need for more intensive theory-based interventions that incorporate multiple behaviour change techniques. Online tools such as Human OS, which incorporate multiple behaviour change techniques capable of supporting the daily health practice of its users in the long term through the use of quantified self, could prove very beneficial to Physiotherapists. In an age where NMSK conditions linked to physical inactivity are significantly increasing, Physiotherapists will be increasingly expected to assume the role of a health coach.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 World Health Organisation., 2014. Health Topics Physical Activity. [online]. [viewed 29 October 2014]. Available from: http://www.who.int/topics/physical_activity/en/

- ↑ NHS Health Scotland. 2012. Costing the Burden of Ill Health Related to Physical Inactivity for Scotland. [online]. [viewed: 06 November 2014]. Available from: http://www.healthscotland.com/uploads/documents/20437-D1physicalinactivityscotland12final.pdf.

- ↑ Janssen I., 2012. Health Care Cost of Physical Inactivity in Canadian Adults. Applied Physiology, Nutrition and Metabolism. [online]. Vol. 37. 803-806. [viewed: 06 November 2014]. Available From: http://www.nrcresearchpress.com/doi/pdf/10.1139/h2012-061

- ↑ Jinguan, L., 2013. Improving Chronic Disease Self-Management through Social Networks. Population Health Management. 16 (5), pp. 285-287.

- ↑ Dr Mike Evans. 23 and 1/2 hours: What is the single best thing we can do for our health?. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aUaInS6HIGo [last accessed 30/10/14]

- ↑ Pate RR, Pratt M, Blair SN, Haskell WL, Macera CA, Bouchard C, Buchner D, Ettinger W, Heath GW, King AC, Kriska A. Physical activity and public health: a recommendation from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American College of Sports Medicine. Jama. 1995 Feb 1;273(5):402-7.

- ↑ Pronk NP, Kottke TE. Physical activity promotion as a strategic corporate priority to improve worker health and business performance. Prev Med. 2009;49(4):316-321. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.06.025

- ↑ Hugh Saunders. National Physical Activity Guidelines. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=srpxGX0M5bE [last accessed 30/10/14]

- ↑ Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology. Canadian physical activity guidelines. Canadian sedentary behaviour guidelines.2014. [online]. [viewed 06 November 2014]. Available from: http://www.csep.ca/english/view.asp?x=804

- ↑ GOV.UK.2014. Guidance UK Physical Activity Guidelines. [online]. [viewed 06 November 2014]. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/uk-physical-activity-guidelines

- ↑ Health.2014. The United States of America Physical Activity Guidelines. [online]. [viewed 06 November 2014]. Available from:http://www.health.gov/paguidelines/guidelines/

- ↑ Brownell KD. The humbling experience of treating obesity: Should we persist or desist?. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2010 Aug 1;48(8):717-9.

- ↑ Department of Health 2012. Long Term Compendium of Information Third Edition. [online]. [viewed 03 November 2014]. Available from: http:// tinyurl.com/m9zyqe8

- ↑ National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Behaviour change: the principles for effective interventions. London: NICE public health guidance. 2007;6.[Online].[Viewed 20 November 2014]. Available from: http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ph6/chapter/2-considerations#definitions

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 Cooper, S., and Ratele, K. 2014. Psychology serving humanity: Proceedings of the 30th International Congress of Psychology, Volume 2: Western psychology.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Skinner, B, F., and Holland, J, G. 1961. The analysis of behavior: A program for self-instruction. New York, US, McGraw-Hill.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 DFW.2008.The Theory of Reasoned Action[Online}.[Viewed 20 November 2014].Available from:http://www.fw.msu.edu/outreachextension/thetheoryofreasonedaction.htm

- ↑ Bandura, Albert.1998.Health Promotion from the Perspective of Social Cognitive Theory[Online].[Viewed 20 November 2014].Available from:http://www.uky.edu/~eushe2/Bandura/Bandura1998PH.pdf

- ↑ Prochaska, J. O., Velicer, W. F., Rossi, J. S., Goldstein, M. G., Marcus, B. H., Rakowski, W., Fiore, C., Harlow, L. L., Redding, C. A., Rosenbloom, D., Rossi, S. R. (1994). Stages of change and decisional balance for twelve problem behaviors. Health Psychology, 13, 39-46.

- ↑ Schwarzer, Ralf.2014.The Health Action Process Approach (HAPA)[Online].[Viewed 20 November 2014].Available from:http://userpage.fu-berlin.de/health/hapa.htm

- ↑ Fogg, B.J.2011.What Causes Behavior Change?[Online].[Viewed 20 November 2014]. Available from:http://www.behaviormodel.org/

- ↑ UTAH County Well 4 Life.2014. Positive Attidue Development Workshop. [Online] Available at: http://utahcountywell4life.blogspot.co.uk/2014/02/positive-attitude-development-workshop.html Last Accessed 5/11/14

- ↑ Bandura, A. (1977). Self-Efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavior change. Psychological Review, 84, 191-215

- ↑ Fjeldsoe, B., et al. 2011. Systematic review of maintenance of behavior change following physical activity and dietary interventions. Health Psychology, 30(1), pp.99-109.

- ↑ Oliveira VC, Ferreira PH, Maher CG, Pinto RZ, Refshauge KM, Ferreira ML. Effectiveness of self‐management of low back pain: Systematic review with meta‐analysis. Arthritis care & research. 2012 Nov;64(11):1739-48.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Harding V, Watson PJ. Increasing activity and improving function in chronic pain management. Physiotherapy. 2000 Dec 1;86(12):619-30.

- ↑ Swan M. Sensor mania! the internet of things, wearable computing, objective metrics, and the quantified self 2.0. Journal of Sensor and Actuator networks. 2012 Dec;1(3):217-53.

- ↑ Lorig KR, Holman HR. Self-management education: history, definition, outcomes, and mechanisms. Annals of behavioral medicine. 2003 Aug 1;26(1):1-7.

- ↑ Crowe M, Whitehead L, Jo Gagan M, Baxter D, Panckhurst A. Self‐management and chronic low back pain: a qualitative study. Journal of advanced nursing. 2010 Jul;66(7):1478-86.

- ↑ Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC, Norcross JC. In search of how people change: applications to addictive behaviors. American Psychologist 47(9), pp. 1002–1114

- ↑ The Chartered Society Of Physiotherapists. 2014. Neuroscience: Why do I ignore what some of my patients say? Understanding Pain and Behaviour [online] London: [viewed on 6th Nov 2014]. Available from: http://www.csp.org.uk/events/neuroscience-why-do-some-my-patients-ignore-what-i-say-7-may-2014-london

- ↑ Kawi J. Predictors of self-management for chronic low back pain. Applied Nursing Research. 2014 Nov 1;27(4):206-12.. [online]. [viewed 06 April 2014]. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.apnr.2014.02.003

- ↑ Cooper K, Smith BH, Hancock E. Patients’ perceptions of self-management of chronic low back pain: evidence for enhancing patient education and support. Physiotherapy. 2009 Mar 1;95(1):43-50.

- ↑ Phillips J. The need for an integrated approach to supporting patients who should self manage. Self Care. 2012;3:33-41.

- ↑ Health Foundation., 2011. The Health Foundation Evidence: Helping People Help Themselves [online]. . [Viewed 06 Nov 2014] Available from: http://renaltsar.blogspot.co.uk/2011/12/what-is-selfmanagement-support.html

- ↑ Bos C, Van der Lans IA, Van Rijnsoever FJ, Van Trijp HC. Understanding consumer acceptance of intervention strategies for healthy food choices: a qualitative study. BMC public health. 2013 Dec;13(1):1073.

- ↑ Mason, P. and Butler, C. 2010. Health Behaviour Change. 2nd ed. Edinburgh, Churchill Livingstone.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 MINT Excellence in Motivational Interviewing. 2014 Welcome to the motivational interviewing website [online]. [viewed 17th November 2014]. Available from: http://motivationalinterviewing.org/

- ↑ Rollnick S, Butler CC, Kinnersley P, Gregory J, Mash B. Motivational interviewing. Bmj. 2010 Apr 27;340:c1900.[online]. [viewed on 17th November 2014]. Available from: http://www.bmj.com/content/340/bmj.c1900

- ↑ Peng K, Bourret D, Khan U, Truong H, Nixon S, Shaw J, McKay S. Self-management goal setting: identifying the practice patterns of community-based physical therapists. Physiotherapy Canada. 2014 Apr;66(2):160-8.

- ↑ Decisions Skills. Smart Goals - Overview. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1-SvuFIQjK8 [Last Accessed:7/11/14]

- ↑ Appelboom G, Camacho E, Abraham ME, Bruce SS, Dumont EL, Zacharia BE, D’Amico R, Slomian J, Reginster JY, Bruyère O, Connolly ES. Smart wearable body sensors for patient self-assessment and monitoring. Archives of public health. 2014 Dec;72(1):28.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 43.2 43.3 Lupton D. Quantifying the body: monitoring and measuring health in the age of mHealth technologies. Critical Public Health. 2013 Dec 1;23(4):393-403.

- ↑ Lowe SA, ÓLaighin G. Monitoring human health behaviour in one's living environment: a technological review. Medical engineering & physics. 2014 Feb 1;36(2):147-68.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 45.2 Shull PB, Jirattigalachote W, Hunt MA, Cutkosky MR, Delp SL. Quantified self and human movement: a review on the clinical impact of wearable sensing and feedback for gait analysis and intervention. Gait & posture. 2014 May 1;40(1):11-9.

- ↑ Appelboom G, Yang AH, Christophe BR, Bruce EM, Slomian J, Bruyère O, Bruce SS, Zacharia BE, Reginster JY, Connolly Jr ES. The promise of wearable activity sensors to define patient recovery. Journal of Clinical Neuroscience. 2014 Jul 1;21(7):1089-93.

- ↑ Vuori IM, Lavie CJ, Blair SN. Physical activity promotion in the health care system. InMayo clinic proceedings 2013 Dec 1 (Vol. 88, No. 12, pp. 1446-1461). Elsevier.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 48.2 Dobkin BH, Dorsch A. The promise of mHealth: daily activity monitoring and outcome assessments by wearable sensors. Neurorehabilitation and neural repair. 2011 Nov;25(9):788-98.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 Appelboom G, Sussman ES, Raphael P, Juilliere Y, Reginster JY, Connolly ES. A critical assessment of approaches to outpatient monitoring. Current Medical Research and Opinion, vol. 30, no. 7, pp. 1383-1384.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 50.2 50.3 Lupton D. 2013b. Digitized health promotion: Personal responsibility for health in the web 2.0 era [online], Sydney Health Society Group working paper no. 5, Available from: http://ses.library.usyd.edu.au/bitstream/2123/9190/1/Working%20paper%20No.%205%20-%20Digitized%20health%20promotion.pdf [accessed 10th Nov 2014]

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 Peter Drucker. Management Consultant and Presidential Medal of Freedom. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V08dWCtDyd8 [last accessed 4/11/14]

- ↑ Hanson C, West J, Neiger B, Thackeray R, Barnes M, McIntyre E. Use and acceptance of social media among health educators. American Journal of Health Education. 2011 Jul 1;42(4):197-204.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 53.2 Lee J-M., Kim Y, and Welk G,J. 2014. Validity of Consumer-Based Physical Activity Monitoring, Journal of American College of Sports Medicine, pp. 1840-1848.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 54.2 54.3 Lyons EJ, Lewis ZH, Mayrsohn BG, Rowland JL. Behavior change techniques implemented in electronic lifestyle activity monitors: a systematic content analysis. Journal of medical Internet research. 2014;16(8):e192.

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 Takacs J, Pollock CL, Guenther JR, Bahar M, Napier C, Hunt MA. Validation of the Fitbit One activity monitor device during treadmill walking. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport. 2014 Sep 1;17(5):496-500.

- ↑ Giannakidou DM, Kambas A, Ageloussis N, Fatouros I, Christoforidis C, Venetsanou F, Douroudos I, Taxildaris K. The validity of two Omron pedometers during treadmill walking is speed dependent. European journal of applied physiology. 2012 Jan 1;112(1):49-57.

- ↑ Ryan CG, Grant PM, Tigbe WW, Granat MH. The validity and reliability of a novel activity monitor as a measure of walking. British journal of sports medicine. 2006 Sep 1;40(9):779-84.

- ↑ Tudor-Locke C, Craig CL, Aoyagi Y, Bell RC, Croteau KA, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Ewald B, Gardner AW, Hatano Y, Lutes LD, Matsudo SM. How many steps/day are enough? For older adults and special populations. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2011 Dec;8(1):80.

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 Tsavourelou A, Rowe P, Babatsikou F, Koutis C. VALIDATION OF THE ACTIVPAL IN THE HEALTH PROMOTION CONTEXT. Health Science Journal. 2009 Apr 1;3(2).

- ↑ PALTECHNOLOGIES. 2014. Product portfolio (online), available: http://www.paltech.plus.com/products.htm [accessed 10th November 2014]

- ↑ Dowd KP, Harrington DM, Donnelly AE. Criterion and concurrent validity of the activPAL™ professional physical activity monitor in adolescent females. PloS one. 2012 Oct 19;7(10):e47633.

- ↑ Bassett JD, John D, Conger SA, Rider BC, Passmore RM, Clark JM. Detection of lying down, sitting, standing, and stepping using two activPAL monitors. Medicine and science in sports and exercise. 2014 Oct;46(10):2025-9.

- ↑ Davies G, Reilly JO, McGowan A, Dall P, Granat M, Paton J. Validity, practical utility, and reliability of the activPAL in preschool children. Medicine and science in sports and exercise. 2012;44(4):761-8.

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 Grant PM, Ryan CG, Tigbe WW, Granat MH. The validation of a novel activity monitor in the measurement of posture and motion during everyday activities. British journal of sports medicine. 2006 Dec 1;40(12):992-7.

- ↑ O’Donoghue D, Kennedy N. Validity of an activity monitor in young people with cerebral palsy gross motor function classification system level I. Physiological measurement. 2014 Oct 23;35(11):2307.

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 66.2 Fritz T, Huang EM, Murphy GC, Zimmermann T. Persuasive technology in the real world: a study of long-term use of activity sensing devices for fitness. InProceedings of the SIGCHI conference on human factors in computing systems 2014 Apr 26 (pp. 487-496). ACM.

- ↑ Daniel Pardi. 2014. How Quantified Self Technologies Will Help Us Live More Like Our Ancestors. [Online] Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vp2k0J80l3U Last Accessed: [17/11/14]

- ↑ Moffet et al.1997.The influence of the physiotherapist-patient relationship on pain and disability

- ↑ Estrin D, Sim I. Open mHealth architecture: an engine for health care innovation. Science. 2010 Nov 5;330(6005):759-60.

- ↑ Strickland E. The FDA takes on mobile health apps. IEEE Spectrum. 2012 Sep. (Online) Available: http://spectrum.ieee.org/biomedical/devices/the-fda-takes-on-mobile-health-apps [accessed 5th November 2014]

- ↑ Raskin R. Digital health and the monitored life. Accessed from Huff Post Tech website. 2012.. (Online), available: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/robin-raskin/digital-health-and-the-mo_b_2301222.html [accessed 5th November 2014]

- ↑ Ho K. Health-e-Apps: A project to encourage effective use of mobile health applications. BC medical journal. 2013;55(10):458-60.

- ↑ Clarke A, Steele R. Summarized data to achieve population-wide anonymized wellness measures. In2012 Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society 2012 Sep (pp. 2158-2161). IEEE.

- ↑ PWC.Why mobile technology may well define the future of healthcare... for everyone.2012. Available at:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qkm_7XUDqIY [Online] Last Accessed:21/11/14

- ↑ Legris, P., et al. 2003. Why do people use information technology? A critical review of the technology acceptance model. Information and Management, 40(3), pp.191-204.

- ↑ Rutherford JJ. Wearable technology. IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Magazine. 2010 May 10;29(3):19-24.

- ↑ Crawford R. Health as a meaningful social practice. Health:. 2006 Oct;10(4):401-20.

- ↑ 78.0 78.1 Ho K. Health-e-Apps: A project to encourage effective use of mobile health applications. BC medical journal. 2013;55(10):458-60..

- ↑ THE SCOTTISH GOVERNMENT. 2012. AHPs as agents of change in health and social care- The National Delivery Plan for the Allied Health Professions in Scotland 2012-2015 (online), available: http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Publications/2012/06/9095/downloads#res395491 [accessed 17th Sept 2014]

- ↑ Pertola, A.E. 2013. Quantified Self and Mobile Health Monitoring, MSc Thesis, Technical University of Denmark.

- ↑ IMS Health.2014.Patient Journey[online].[viewed 12 November 2014].Available from: https://developer.imshealth.com/Content/pdf/IIHI_Patient_Apps_Report.pdf

- ↑ Booth, F.W., Chakravarthy, M.V. and Spangenburg, E.E. 2002. Exercise and gene expression: physiological regulation of the human genome through physical activity. The Journal of physiology, 543 (Pt 2) Sep 1, pp.399-411.

- ↑ Harding, V., and Williams, A, C. 1995. Applying Psychology to Enhance Physiotherapy Outcome. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice, 11(3), pp. 129-132.