Zoonotic Diseases: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 101: | Line 101: | ||

6. [[Leptospirosis]] | 6. [[Leptospirosis]] | ||

is caused by | a bacterial disease that affects humans & animals. It is caused by the bacteria genus Leptospira. This bacteria is spread through urine of infected animals, which can get into water or soil and can survive for weeks to months. The most common method of transmission is through direct contact with infected urine or other bodily fluids such as saliva, or contaminated water, soil, or food. | ||

* | |||

7. Plague ([http://www.cdc.gov/healthypets/diseases/yersinia.htm Yersinia enterocolitica], Yersinia pestis) | 7. Plague ([http://www.cdc.gov/healthypets/diseases/yersinia.htm Yersinia enterocolitica], Yersinia pestis) | ||

Revision as of 12:14, 5 March 2020

Original Editors - Kristy Rizzo from Bellarmine University's Pathophysiology of Complex Patient Problems project.

Top Contributors - Kristine Rizzo, Lucinda hampton, Elaine Lonnemann, Admin, Tony Lowe, Kim Jackson, WikiSysop, Nupur Smit Shah and 127.0.0.1

Introduction[edit | edit source]

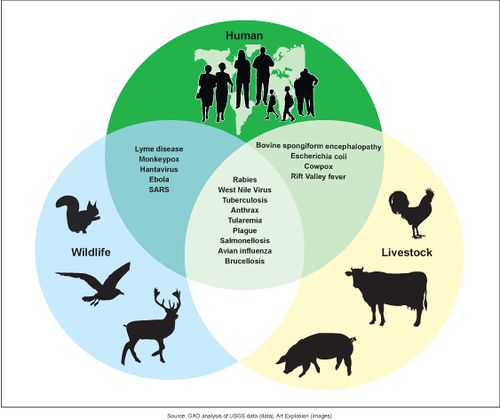

A zoonotic disease is any disease or infection that is transmissible from vertebrate animals to humans. [1],[2] Recently emerged zoonotic diseases include globally devastating diseases such as:

- Coronaviruses (CoV), a large family of viruses that cause illness ranging from the common cold to more severe diseases such as Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS-CoV),Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS-CoV) and novel coronavirus (nCoV)[3]

- Ebola virus disease

- Highly pathogenic avian influenza

- Bovine spongiform encephalopathy [4]

Key Points

- Nearly two-thirds of human infectious diseases arise from pathogens shared with wild or domestic animals

- Endemic and enzootic zoonoses cause about a billion cases of illness in people and millions of deaths every year, and emerging zoonoses are a rising threat to global health, having caused hundreds of billions of US dollars of economic damage in the past 20 years

- Ecological and evolutionary perspectives can provide valuable insights into pathogen ecology and can inform zoonotic disease-control programmes

- Anthropogenic practices (ie those caused by humans or their practices) eg. changes in land use, animal production systems, and widespread antimicrobial applications, affect zoonotic disease transmission

- Risks are to all countries; as global trade and travel expands, zoonoses are increasingly posing health concerns for the global medical community

- Multisectoral collaboration, including clinicians, public health scientists, ecologists and disease ecologists, veterinarians, economists, and others is necessary for effective management of the causes and prevention of zoonotic diseases[5]

How do Zoonoses spread[edit | edit source]

Because of the close connection between people and animals, it’s important to be aware of the common ways people can get infected with germs that can cause zoonotic diseases. These can include:

- Direct contact: Coming into contact with the saliva, blood, urine, mucous, feces, or other body fluids of an infected animal. Examples include petting or touching animals, and bites or scratches.

- Indirect contact: Coming into contact with areas where animals live and roam, or objects or surfaces that have been contaminated with germs. Examples include aquarium tank water, pet habitats, chicken coops, barns, plants, and soil, as well as pet food and water dishes.

- Vector-borne: Being bitten by a tick, or an insect like a mosquito or a flea.

- Foodborne: Each year, 1 in 6 Americans get sick from eating contaminated food. Eating or drinking something unsafe, such as unpasteurized (raw) milk, undercooked meat or eggs, or raw fruits and vegetables that are contaminated with feces from an infected animal. Contaminated food can cause illness in people and animals, including pets.

- Waterborne: Drinking or coming in contact with water that has been contaminated with feces from an infected animal.[6]

Approaches for Zoonotic Disease Control[edit | edit source]

Mitigating the impact of endemic and emerging zoonotic diseases of public health importance requires multisectoral collaboration and interdisciplinary partnerships. Collaborations across sectors relevant to zoonotic diseases, particularly among human and animal (domestic and wildlife) health disciplines, are essential for quantifying the burden of zoonotic diseases, detecting and responding to endemic and emerging zoonotic pathogens, prioritizing the diseases of greatest public health concern, and effectively launching appropriate prevention, detection, and response strategies.

These structures must be in place before an outbreak, epidemic, or pandemic occurs to have an effective, coordinated public- and animal-health response. Countries that lack a well-functioning coordination mechanism could fail to rapidly detect and effectively respond to emerging health threats, which could spread to other countries and threaten global health security.[4]

Classes of Zoonoses[edit | edit source]

Including viruses, bacteria, parasites, and fungi.

Viral Zoonoses[edit | edit source]

6 Common Viral Zoonoses[edit | edit source]

- Coronaviruses (CoV) are a large family of viruses that cause illness ranging from the common cold to more severe diseases such as Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS-CoV) and Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS-CoV). A novel coronavirus (nCoV) is a new strain that has not been previously identified in humans.

- Detailed investigations found that SARS-CoV was transmitted from civet cats to humans and MERS-CoV from dromedary camels to humans. Several known coronaviruses are circulating in animals that have not yet infected humans.

2. Ehrlichiosis

3. Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever (Rickettsia )

4. Rabies

Rabies is an infectious, zoonotic disease that destroys brain cells and can lead to death if left untreated before symptoms appear. It is caused by a virus that lives in the saliva of a host or carrier and can be transmitted by being bitten by the carrier or if the infected saliva enters an open wound or mucous membranes. Rabies has been reported as being transmitted to people after breathing in air from caves that contained millions of bats and through organ transplants from an infected person. The most common sources of infections for humans are from wild animals and dogs.[7]

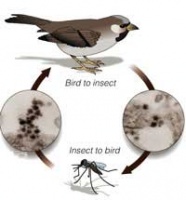

A viral disease spread by mosquitoes which can affect birds, horses, and other mammals[8]

Mosquitoes become infected when they feed on infected birds. Infected mosquitoes can then spread WNV to humans and other animals when they bite. About one in 150 people infected with WNV will develop severe illness. The severe symptoms can include high fever, headache, neck stiffness, stupor, disorientation, coma, tremors, convulsions, muscle weakness, vision loss, numbness and paralysis. These symptoms may last several weeks, and neurological effects may be permanent.

Up to 20 percent of the people who become infected have symptoms such as fever, headache, and body aches, nausea, vomiting, and sometimes swollen lymph glands or a skin rash on the chest, stomach and back.

Symptoms can last for as short as a few days, though even healthy people have become sick for several weeks. Approximately 80 percent of people (about 4 out of 5) who are infected with WNV will not show any symptoms at all. People typically develop symptoms between 3 and 14 days after they are bitten by the infected mosquito. There is no specific treatment for WNV infection. In cases with milder symptoms, symptoms pass on their own. In more severe cases, people usually need to go to the hospital where they can receive supportive treatment including intravenous fluids, help with breathing, and nursing care.[9] Personal protective measures are the primary way to avoid contracting the virus.[1]

6. Equine Encephalitis

A mosquito borne infection normally maintained in nature by a cycle from an arthropod vector to a vertebrate reservoir host.[1] Although some people experience it only as a mild illness, eastern equine encephalitis is fatal in about one-third of the cases. Symptoms of eastern equine encephalitis usually appear three to 10 days after a bite by an infected mosquito.[10] A vaccine exists for horses but not for humans.[1] Personal protective measures are the primary way to avoid contracting the virus.[1]

Bacterial Zoonoses[edit | edit source]

10 Common Bacterial Zoonoses[edit | edit source]

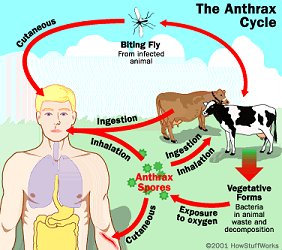

- Anthrax

Anthrax is an acute infectious disease caused by the spore-forming bacterium Bacillus anthracis[11], a microbe that lives in the soil.[12] Anthrax most commonly occurs in wild and domestic mammals (cattle, sheep, goats, camels, antelopes, and other herbivores), but it can also occur in humans when they are exposed to infected animals or to tissue from infected animals.[11] Anthrax can occur in three forms: cutaneous, inhalation, and gastrointestinal.[11][12]

2. Bartonella (Cat Scratch Fever)

Cat scratch disease (CSD) is a bacterial disease caused by Bartonella henselae. Most people with CSD have been bitten or scratched by a cat and developed a mild infection at the point of injury. Lymph nodes, especially those around the head,

neck, and upper limbs, become swollen. Additionally, a person with CSD may experience fever, headache, fatigue, and a poor appetite.[8] Bartonella will begin in the human as a pustule that will gradually progress to regional lymphadenopathy which can last for months (or become a systemic illness in immunocompromised patients). In addition to the cat or dog scratch, bartonella can also be transmitted through the feces of fleas.[1]

- Lyme disease or Lyme borreliosis is the most commonly transmitted tick-borne infection in the United States and among the most frequently diagnosed tick-borne infections worldwide[13].

4. Brucellosis

- Brucellosis is a zoonotic infection transmitted from animals to humans by the ingestion of infected food products, direct contact with an infected animal, or inhalation of aerosols.[14]

- The timely and accurate diagnosis of human brucellosis continues to challenge clinicians because of its non-specific clinical features, slow growth rate in the blood culture, and the complexity of its serodiagnosis.[14]

- Four different species of Brucella are known to infect humans: B. abortus (cattle), B. suis (swine), B. melitensis (goats/sheep) and B. canis (dogs).

- B. abortus and B. canis cause a mild fever whereas B. suis causes a more severe infection which can lead to destruction of the lymphoreticular organs and kidney.

- B.melitensis is the cause of most severe prolonged recurring disease.

- The bacteria enter the human host through mucous membranes. The bacteria localize in the regional lymph nodes, where they proliferate intracellularly. If the Brucella organisms are not destroyed or contained in the lymph nodes, the bacteria are released from the lymph nodes resulting in septicemia.[15]

- Brucellosis in human beings is rarely fatal, but can lead to severe debilitation and disability[14]

- Symptoms include fever, chills, sweats, fatigue, myalgia, profound muscle weakness, and anorexia.[15]

- There is currently no human vaccine available.[16].[1]

5. Ehrlichiosis

The general name used to describe several bacterial diseases that affect animals and humans.

- Human ehrlichiosis is a disease caused by at least three different ehrlichial species in the United States: Ehrlichia chaffeensis, Ehrlichia ewingii, and a third Ehrlichia species provisionally called Ehrlichia muris-like (EML).

- Ehrlichiae are transmitted to humans by the bite of an infected tick.

- Symptoms usually occur within 1-2 weeks following a tick bite[17][18] and include fever, headache, fatigue, and muscle aches.

- Ehrlichios is is diagnosed based on symptoms, clinical presentation, and later confirmed with specialized laboratory tests.

- Treatment for adults and children of all ages is doxycycline.[17]

a bacterial disease that affects humans & animals. It is caused by the bacteria genus Leptospira. This bacteria is spread through urine of infected animals, which can get into water or soil and can survive for weeks to months. The most common method of transmission is through direct contact with infected urine or other bodily fluids such as saliva, or contaminated water, soil, or food.

7. Plague (Yersinia enterocolitica, Yersinia pestis)

A rare bacterial disease associated with wild rodents, cats, and fleas.[8]Yersiniosis is a disease caused by the bacterium Yersinia enterocolitica[19], or yersinia pestis (a gram negative coccobacillus).[20]

Plague (yersinia pestis) is the disease known in the middle ages as black death due to the gangrene and blackening of various body parts associated with this disease.[15] However people with yersiniosis can have different symptoms depending on age.

8. Rickettsia (Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever)

- A disease caused by the bacterium Rickettsia rickettsii, which is carried by ticks.

- People usually start having fevers and feeling nauseous about a week after being bitten by a tick.

- A few days after the fever begins people will often have a rash, usually on the arms or ankles. They also may have pain in their joints, stomach pain, and diarrhea.[8]

- When you remove ticks from any animal, the crushed tick or its parts can also pass this disease through any cuts or scrapes on your skin.[8]

9. Methicillin Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus (MRSA)

Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus (MRSA) is defined as a type of bacterial staph infection that is non-responsive to antibiotics normally prescribed to treat such infections.[21] MRSA was first described in 1961-1962 in a patient whose infection was resistant to the drug Methicillin, which was discovered in 1960.The incidence of MRSA greatly increased in the United States in the 1980s and was especially emerging in patients who used intravenous drugs[22].

The bacteria from which MRSA arises, staphylococcus aureus, is found in the skin and in the nostrils of one third of all people and do not show any symptoms of having been exposed to the bacteria. These carriers of the bacteria are then exposing the bacteria to all of the items that they touch as well as expelling it into the air where it will remain until the item is next cleaned.

10. Streptococcus suis is a zoonotic pathogen that infects pigs and can occasionally cause serious infections in humans. S. suis infections occur sporadically in humans throughout Europe and North America, but a recent major outbreak has been described in China with high levels of mortality. The mechanisms of S. suis pathogenesis in humans and pigs are poorly understood.[23]

Fungal Zoonoses[edit | edit source]

Fungal infections associated with zoonotic transmission are an important public health problem worldwide . A number of these infections are among the group of the most common fungal diseases, such as: dermatophytosis, sporotrichosis , and histoplasmosis.[24]

1.Dermatomycoses are caused by fungal spores which remain viable for long periods on carrier animals. Exposure to reservoir hosts harboring different dermatophytes determines the type and incidence of infection in humans. Pets may also acquire disease from humans. Dermatomycoses can be transmitted directly or indirectly through contact with asymptomatic animals or skin lesions on infected animials, contaminated bedding or equipment, fungi in the air, in dust, or on surfaces of the room. The disease in rodents or in cats is often asymptomatic and not recognized until people are affected, but dogs will often show classic skin lesions. Varying severity of dermatitis occurs with local loss of hair. Deeper invasion produces a mild inflammatory reaction which increases in severity with the development of hypersensitivity. In humans, the disease is often mild and self limiting. Scaling, redness, and occasionally vesicles or fissures will be present with thickening and discoloring of nails. A circular lesion with a clear center may also be present.[25]

2. Histoplasmosis is a fungal disease associated with bat guano (stool).[8] The infection enters the body through the lungs. Histoplasma fungus grows as a mold in the soil, and infection results from breathing in airborne particles. Soil contaminated with bird or bat droppings may have a higher concentration of histoplasma. There may be a short period of active infection, or it can become chronic and spread throughout the body. Histoplasmosis may have no symptoms. Most people who do develop symptoms will have a flu-like syndrome and lung (pulmonary) complaints related to pneumonia or other lung involvement. Those with chronic lung disease (such as emphysema and bronchiectasis) are at higher risk of a more severe infection.[26]

4. Blastomycosis generally results from inhalation of Blastomyces dermatitidis conidia following exposure to contaminated soil in an endemic area. Primary infections commonly involve the lungs, although secondary dissemination to other body sites may occur.[27]

- Coccidioidomycosis is an infection with the spores of the fungus Coccidioides immitis. It is most commonly seen in the

desert regions of the southwestern United States and in Central and South America. The infection starts in the lungs and is contracted by breathing in fungal particles from soil. Most people with this infection do not have symptoms. Some may have cold or flu-like symptoms or symptoms of pneumonia. If symptoms occur, they typically start 5 to 21 days after being

exposed to the fungus. Symptoms include, change in mental status, chest pain, cough (possibly hemoptysis, fever, headache, joint

stiffness/pain, loss of appetite, muscle aches, neck stiffness, night sweats, painful red lumps on lower legs (erythema nodosum), sensitivity to light, weight loss, and wheezing.[28]

- Cryptococcosis is a fungal disease caused by Cryptococcus neoformans or Cryptococcus gattii. This fungus is found in the droppings of wild birds (such as pigeons). When dried bird droppings are stirred up, this can transfer dust containing Cryptococcus neoformans into the air. People can stir up this dust and then breathe it in when they work, play, or walk in areas where birds have been. Pets, such as dogs and cats, can also get sick with cryptococcosis from this dust, but people do not get cryptococcosis from directly from dogs and cats. Cryptococcosis can cause serious symptoms of lung, brain and spinal cord disease, such as headaches, fever, cough, shortness of breath, and night sweats.[29]

Parasitic Zoonoses[edit | edit source]

Most Common Parasitic Zoonoses[edit | edit source]

A parasitic disease associated with cats, dogs and their environment.[8] Toxocara canis is an infection transmitted from animals to humans caused by the parasitic roundworms commonly found in the intestine of dogs (Toxocara canis) and cats (T. cati). The most common Toxocara parasite of concern to humans is T. canis, which puppies usually contract from the mother before birth or from her milk. The larvae mature rapidly in the puppy’s intestine; when the pup is 3 or 4 weeks old, they begin to produce large numbers of eggs that contaminate the environment through the animal’s stool. The eggs soon develop into infective larvae. Humans can become infected after accidentally ingesting infective Toxocara eggs in soil or other contaminated surfaces. In most cases, Toxocara infections are not serious, and many people, especially adults infected by a small number of larvae, may not notice any symptoms. The most severe cases are rare, but are more likely to occur in young children, who often play in dirt, or eat dirt (pica) contaminated by dog or cat stool.[30]

Ancylostoma caninum is a parasitic disease associated with dogs and their environment.[8] Animals can indirectly pass hookworm to humans. Animals that are infected pass hookworm eggs in their stools. The eggs can hatch into larvae, and both eggs and larvae may be found in dirt where animals have been. Eggs or larvae can get into the human body through direct contact with the dirt. For example, this can happen if a child is walking barefoot or playing in an area where dogs or cats have been (especially puppies or kittens). If a person accidentally contracts animal hookworm eggs, then the larvae that hatch out of the eggs can reach the intestine and cause bleeding, inflammation (swelling), and abdominal pain. People can get painful and itchy skin infections when animal hookworm larvae move through their skin.[31]

Echinococcosis (tapeworm)

The adult worm affects various final hosts such as domestic dogs and wild carnivores like foxes, coyotes, wolves and jackals. The eggs are spread through their faeces. Intermediate hosts are sheep, cattle, swine, goats,

equines, camelids and cervids. They acquire the infection by ingestion of the infective eggs during grazing. Carnivores acquire the infection by ingestion of infected raw material of the intermediate hosts (mostly viscera). Like the intermediate hosts, humans acquire the infection by ingestion of infective eggs.

Prevention[edit | edit source]

The best way to protect oneself from many of these zoonotic diseases is to practice good hygiene after handling animals or their waste. Washing hands thoroughly with hot, soapy water after any contact will help prevention contraction of zoonotic diseases.[2] In addition screening newly received animals, conducting a routine sanitization of the contaminated environment, equipment, and caging, wearing gloves and protective clothing will help decrease the possiblity of contracting a zoonotic disease.[25]

The four principal means of preventing spread of zoonoses are[1]

1. parasite recognition and control

2. vaccination programs

3. sanitation methods

4. behavior training to prevent bites and scratches

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 Van Dyke JB. Veterinary zoonoses, what you need to know before you treat that puppy! American Physical Therapy Association Combined Sections Meeting; 2011 Feb 11; New Orleans, Louisianna.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Oregon Veterinary Medical Association. Zoonotic Diseases and Horses.fckLRhttp://oregonvma.org/care-health/zoonotic-diseases-horses. (accessed 8 March 2011).

- ↑ WHO Corona virus Available from:https://www.who.int/health-topics/coronavirus (last accessed 5.3.2020)

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Belay ED, Kile JC, Hall AJ, Barton-Behravesh C, Parsons MB, Salyer S, Walke H. Zoonotic disease programs for enhancing global health security. Emerging infectious diseases. 2017 Dec;23(Suppl 1):S65. Available from:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5711319/ (last accessed 5.3.2020)

- ↑ Karesh WB, Dobson A, Lloyd-Smith JO, Lubroth J, Dixon MA, Bennett M, Aldrich S, Harrington T, Formenty P, Loh EH, Machalaba CC. Ecology of zoonoses: natural and unnatural histories. The Lancet. 2012 Dec 1;380(9857):1936-45. Available from:https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(12)61678-X/fulltext (last accessed 5.3.2020)

- ↑ CDC Zoonotic diseases Available from:https://www.cdc.gov/onehealth/basics/zoonotic-diseases.html (last accessed 5.3.2020)

- ↑ RABIES. (n.d.), [cited March 17, 2011]; Available from: Funk & Wagnalls New World Encyclopedia

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 8.6 8.7 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Healthy Pets Healthy People. http://www.cdc.gov/healthypets/browse_by_diseases.htm (accessed 26 Feb 2011).

- ↑ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Division of Vector-Borne Infectious Diseases. West-Nile Virus. http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dvbid/westnile/wnv_factsheet.htm (accessed 27 Feb 2011).

- ↑ Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research. Encephalitis. http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/encephalitis/DS00226/DSECTION=causes (accessed 27 Feb 2011).

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Emergency Preparedness and Response. Questions and Answers about Anthrax. http://www.bt.cdc.gov/agent/anthrax/faq/ (accessed 2 March 2011)

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 U.S. National Library of Medicine. National Institute of Health. Medline Plus. Anthrax.http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/anthrax.html (accessed 2 March 2011).

- ↑ Skar GL, Simonsen KA. Lyme Disease. InStatPearls [Internet] 2018 Oct 27. StatPearls Publishing. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK431066/ (last accessed 26.12.2019)

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Christopher S, Umapathy BL, Ravikumar KL. Brucellosis: Review on the recent trends in pathogenicity and laboratory diagnosis. J Lab Physicians 2010;2:55-60

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 University of South Carolina School of Medicine. Microbiology and Immunology On-line. Bacteriology Chapter Seventeen. Zoonoses. http://pathmicro.med.sc.edu/ghaffar/zoonoses.htm (accessed 10 March 2011).

- ↑ Teske SS, Huang Y, Tamrakar SB, Bartrand TA, Weir MH, Haas CN. Animal and human dose-response models for Brucella species. Risk Anal 2011; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21449960?dopt=Abstract (accessed 4 April 2011).

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Ehrlichiosis. http://www.cdc.gov/ehrlichiosis/ (accessed 27 Feb 2011).

- ↑ Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research. Ehrlichiosis. http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/ehrlichiosis/DS00702 (accessed 27 Feb 2011).

- ↑ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Yersinia enterocolitica and Pigs. http://www.cdc.gov/healthypets/diseases/yersinia.htm (accessed 8 March 2011).

- ↑ Iowa State University. Institutional Biosafety Committee. Guidance & Education. Zoonotic Disease Fact Sheets: yersinia pestis. http://compliance.iastate.edu/ibc/guide/zoonoticfactsheets/Yersinia%20Pestis.pdf (accessed 8 March 2011).

- ↑ Mayo Clinic Staff. MRSA infection - Mayo Clinic [Internet]. Mayoclinic.org. 2016.http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/mrsa/basics/definition/con-20024479 (accessed 1 April 2016).

- ↑ Millar B, Loughrey A, Elborn J, Moore J. Proposed definitions of community-associated meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (CA-MRSA). Journal of Hospital Infection. 2007;67(2):109-113. http://eds.b.ebscohost.com.libproxy.bellarmine.edu/ehost/detail/detail?vid=14&sid=71ee6b7e-199d-4adc-8e31-bc94eca59a09%40sessionmgr113&hid=112&bdata=JmxvZ2luLmFzcCZzaXRlPWVob3N0LWxpdmUmc2NvcGU9c2l0ZQ%3d%3d#AN=105828672&db=cin20 (accessed 2 April 2016).

- ↑ Holden et al. Rapid evolution of virulence and drug resistance in the emerging zoonotic pathogen streptococcus suis. PLoS One. 2009; 4(7). e6072. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2705793/(accessed 8 March 2011).

- ↑ Seyedmousavi S, Guillot J, Tolooe A, Verweij PE, De Hoog GS. Neglected fungal zoonoses: hidden threats to man and animals. Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 2015 May 1;21(5):416-25. Available from:https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1198743X15003250 (last accessed 5.3.2020)

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Iowa State University. Institutional Biosafety Committee. Guidance & Education. Zoonotic Disease Fact Sheets: dermatomycoses. http://compliance.iastate.edu/ibc/guide/zoonoticfactsheets/Dermatomycoses.pdf (accessed 8 March 2011).

- ↑ National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine. Histoplasmosis. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmedhealth/PMH0002073/ (accessed 8 March 2011).

- ↑ Veligandla et al. Delayed diagnosis of osseous blastomycosis in two patients following environmental exposure in nonendemic areas. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 118 (4): 536–41. http://ajcp.ascpjournals.org/content/118/4/536 (accessed 8 March 2011).

- ↑ National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine. Coccidioidomycosis. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmedhealth/PMH0002299/ (accessed 8 March 2011).

- ↑ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Healthy Pets Healthy People. Cryptococcosis. http://www.cdc.gov/healthypets/diseases/crptococcus.htm (accessed 8 March 2011).

- ↑ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Parasites. Toxocariasis. http://www.cdc.gov/parasites/toxocariasis/gen_info/faqs.html (accessed 8 March 2011).

- ↑ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Healthy Pets Healthy People. Hookworm Infection and Animals. http://www.cdc.gov/healthypets/diseases/hookworm.htm (accessed 8 March 2011).