Trigeminal neuralgia: A case study: Difference between revisions

Julia Basso (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

==== '''Introduction''' ==== | ==== '''Introduction''' ==== | ||

[[File:Trigeminal nerve distribution.png|thumb|Trigeminal nerve branches in the face. ]] | |||

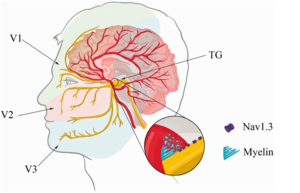

Trigeminal neuralgia (TN) is a unilateral facial pain disorder that involves dysfunction of the 5th cranial nerve (CN V)<ref name=":0">National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Available from: <nowiki>https://www.ninds.nih.gov/Disorders/Patient-Caregiver-Education/Fact-Sheets/Trigeminal-Neuralgia-Fact-Sheet</nowiki> (Accessed 10 May 2021).</ref>. It is typically caused by a compression of the nerve by a blood vessel which overtime causes degeneration of the protective myelin sheath. It may also arise as a complication of multiple sclerosis, a tumor in the area, or arteriovenous malformation. Additionally it can be brought on by physical damage to the nerve from factors like stroke, oral surgery or other facial trauma. The trigeminal nerve exits the brainstem from the pons and branches out into 3 sections that supply the upper, middle and lower portions of the face. The upper most branch, the ophthalmic nerve, supplies sensation to the scalp and forehead. The middle branch, or maxillary nerve, supplies sensation to the nose, lips and cheeks. Finally the lowest branch, the mandibular nerve, supplies sensation to the bottom lip, teeth and gums<ref name=":0" />. The main symptom that people seek medical attention for is the severe attacks of pain located unilaterally on the face over the sensory distribution of the affected nerve(s)<ref>Eller JL, Raslan AM, Burchiel KJ. Trigeminal neuralgia: definition and classification. Neurosurgical focus. 2005 May 1;18(5):1-3.</ref>. The maxillary and mandibular branches are most commonly affected, with the ophthalmic nerve only being affected in 5% of cases<ref name=":1">Patten J. Trigeminal neuralgia. In: Neurological Differential Diagnosis. 2nd ed. London: Springer;1996:373-5.</ref>. The attacks of pain are usually triggered by touch, cold temperatures, and sound<ref name=":2">Nurmikko TJ, Eldridge PR. Trigeminal neuralgia—pathophysiology, diagnosis and current treatment. British journal of anaesthesia. 2001 Jul 1;87(1):117-32.</ref>. | Trigeminal neuralgia (TN) is a unilateral facial pain disorder that involves dysfunction of the 5th cranial nerve (CN V)<ref name=":0">National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Available from: <nowiki>https://www.ninds.nih.gov/Disorders/Patient-Caregiver-Education/Fact-Sheets/Trigeminal-Neuralgia-Fact-Sheet</nowiki> (Accessed 10 May 2021).</ref>. It is typically caused by a compression of the nerve by a blood vessel which overtime causes degeneration of the protective myelin sheath. It may also arise as a complication of multiple sclerosis, a tumor in the area, or arteriovenous malformation. Additionally it can be brought on by physical damage to the nerve from factors like stroke, oral surgery or other facial trauma. The trigeminal nerve exits the brainstem from the pons and branches out into 3 sections that supply the upper, middle and lower portions of the face. The upper most branch, the ophthalmic nerve, supplies sensation to the scalp and forehead. The middle branch, or maxillary nerve, supplies sensation to the nose, lips and cheeks. Finally the lowest branch, the mandibular nerve, supplies sensation to the bottom lip, teeth and gums<ref name=":0" />. The main symptom that people seek medical attention for is the severe attacks of pain located unilaterally on the face over the sensory distribution of the affected nerve(s)<ref>Eller JL, Raslan AM, Burchiel KJ. Trigeminal neuralgia: definition and classification. Neurosurgical focus. 2005 May 1;18(5):1-3.</ref>. The maxillary and mandibular branches are most commonly affected, with the ophthalmic nerve only being affected in 5% of cases<ref name=":1">Patten J. Trigeminal neuralgia. In: Neurological Differential Diagnosis. 2nd ed. London: Springer;1996:373-5.</ref>. The attacks of pain are usually triggered by touch, cold temperatures, and sound<ref name=":2">Nurmikko TJ, Eldridge PR. Trigeminal neuralgia—pathophysiology, diagnosis and current treatment. British journal of anaesthesia. 2001 Jul 1;87(1):117-32.</ref>. | ||

Revision as of 01:52, 14 May 2021

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Trigeminal neuralgia (TN) is a unilateral facial pain disorder that involves dysfunction of the 5th cranial nerve (CN V)[1]. It is typically caused by a compression of the nerve by a blood vessel which overtime causes degeneration of the protective myelin sheath. It may also arise as a complication of multiple sclerosis, a tumor in the area, or arteriovenous malformation. Additionally it can be brought on by physical damage to the nerve from factors like stroke, oral surgery or other facial trauma. The trigeminal nerve exits the brainstem from the pons and branches out into 3 sections that supply the upper, middle and lower portions of the face. The upper most branch, the ophthalmic nerve, supplies sensation to the scalp and forehead. The middle branch, or maxillary nerve, supplies sensation to the nose, lips and cheeks. Finally the lowest branch, the mandibular nerve, supplies sensation to the bottom lip, teeth and gums[1]. The main symptom that people seek medical attention for is the severe attacks of pain located unilaterally on the face over the sensory distribution of the affected nerve(s)[2]. The maxillary and mandibular branches are most commonly affected, with the ophthalmic nerve only being affected in 5% of cases[3]. The attacks of pain are usually triggered by touch, cold temperatures, and sound[4].

This case study describes a 35 year old woman named Ms. R who presented with an insidious onset of left sided facial pain that was impacting her activities of daily living and her occupation. The case of Ms. R’s trigeminal neuralgia was especially unique because she presented with pain in all three branches of the trigeminal nerve, over the entire left side of her face, making her symptoms more severe than what is typical[3]. The case was perplexing due to her young age, complex symptoms, and absence of any notable etiologies. Ms. R’s case was even more intricate due to the nature of her occupation as a news reporter. Her job requires her to be in cold weather conditions and demands a lot of speaking, both of which have been known to trigger the painful attacks that are characteristic of trigeminal neuralgia[4].

The purpose of this case study is to highlight how physiotherapy can play a role within a multidisciplinary team in the management of trigeminal neuralgia. Most of the literature on the role of physiotherapy (PT) with TN patients describes the use of electrical physical agents and modalities to alleviate some of these patients’ pain[5]. These modalities proved to be beneficial for Ms. R, but this case study will also describe the use of other PT interventions that markedly helped Ms. R with her symptoms. This case study will also describe the use of other PT interventions used to help Ms. R with the goal to improve her work performance, reduce her feelings of hopelessness and anxiety, and increase her quality of life. The hope is that this case study can function as a guide for physiotherapists with TN patients that would like to explore alternate techniques that can be applied to help these patients. The case study will offer suggestions for PT treatment techniques that encourage patients to take an active role in their recovery, ultimately getting them to a place where they are able to independently use self-management techniques to help themselves in the long term.

Client Characteristics[edit | edit source]

Ms. R is a 35 year old female, who works as a news reporter. Ms. R first experienced intense pain in the left side of her face one morning while applying makeup around her forehead and eyebrow region. Later that morning, while filming a news report on scene at a road traffic accident, Ms. R began to experience severe pain that was radiating along her left jawline and into her lower gums. Ms. R thought that this stabbing pain may be due to a dental cavity; however, she thought it was strange that the pain seemed to intensify with strong wind gusts and recalled the intense facial pain she had experienced earlier that morning when applying makeup to her face. Initially Ms. R was experiencing 2-3 attacks per day for several weeks, which then escalated to upwards of 10 attacks per day and were frequently triggered by activities of daily life including speaking, chewing, applying makeup and brushing her teeth. After a month of experiencing these debilitating facial pain attacks, Ms. R was prompted to visit her family physician who decided to consult neurology given the unique presentation of her symptoms. Based on Ms. R’s recent history of sudden attacks of intense, stabbing pain (lasting no longer than 2 minutes in length) that are not associated with other neurological deficits or disorders, Ms. R was deemed to have met all diagnostic criteria for Trigeminal Neuralgia as defined by the The International Headache Society[6]. Following further investigation, she was subsequently diagnosed with Classical Trigeminal Neuralgia (CTN). The neurologist prescribed gabapentin[7] for nerve pain control and opted to take a conservative approach to treatment and reassess in 2 months for any improvements in her symptoms before resorting to surgery. Ms. R's neurologist also referred her to physiotherapy for help with symptom management.

Examination Findings[edit | edit source]

Subjective[edit | edit source]

- Patient Profile (PP): 35 y/o female

- History of Present Illness (HPI): Diagnosis of Classical Trigeminal Neuralgia[8] 3 weeks ago on January 5th 2021.

- Patient describes her pain as severe and stabbing attacks. They have increased from 2-3 to 10 or more per day. She rates her pain during attacks as a 9-10/10 on the Numerical Pain Rating Scale (NPRS). Her attacks do not last more than 2 minutes and the pain dissipates shortly after.

- Patient explains that her attacks are provoked by cold temperatures, touching the affected areas of her face, and moving the left side of her face (for example when talking, eating, or putting on makeup).

- Pain is intermittent and has affected activities of daily living and her occupation as a news reporter.

- Pain is felt throughout the left side of the face; most severe pain is in the left lower jaw.

- Patient has found some relief from her medication (gabapentin) but still experiences painful attacks throughout the day.

- Past Medical History (PMHx): Right lateral malleolus fracture (8 years ago, resolved), anxiety

- Medications: Escitalopram Oxalate (10 mg/day); Gabapentin (300 mg/day)[7]

- Social History: Patient currently lives alone with two cats in an apartment on the fourth floor. There is an elevator; however, she prefers to use the stairs.

- Health habits: non-smoker, social drinker (~4 drinks per week), no illicit drug use

- Psychosocial: Patient specifies feelings of frustration due to her diagnosis and the associated symptoms that have affected her daily life and occupation. The uncertainty of her prognosis and possible surgical implications has exacerbated her anxiety. The patient explains that she has avoided meeting with friends or family because of a fear of triggering symptoms.

- Functional Status (Current/Previous)

- Previous = Patient reports living a healthy and active lifestyle with no functional limitations.

- Current = Since the onset of CTN symptoms, patient reports feeling fatigued throughout the day and requires frequent rest periods. When attacks occur, she is unable to function and must stop all activity and remain still until the pain subsides. She is unable to fully perform her occupational duties as her attacks commonly occur while reporting the news. She has a limited number of sick days left and is concerned about how the condition will impact her career.

- Imaging: Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) demonstrates unilateral neurovascular compression with mild morphologic changes of the nerve root; contact observed at root entry[8].

- Precautions/Contraindications:

- Ms. R has been diagnosed with a neurological condition; however, she has been cleared by the physician for physiotherapy treatment.

- Anxiety, lack of social support, minimal opportunity to modify occupational duties.

Objective[edit | edit source]

Observation[edit | edit source]

Trigeminal Nerve (CN V) Tests

- Sensation Testing:[9]

- Light touch applied to the distribution of each branch of the trigeminal nerve:

- Ophthalmic Branch (forehead)

- Maxillary Branch (cheeks)

- Mandibular Branch (chin)

- Sharp/dull testing with a safety pin along trigeminal branch distribution.

- Patient reported severe, sharp pain in trigeminal sensory distribution on the left side of the face.

- Light touch applied to the distribution of each branch of the trigeminal nerve:

- Corneal Reflex:[8]

- Stimulation of the cornea = normal response

- Manual Muscle Test:

- Jaw opening and closing strength = normal

- Reflex Test:[8]

- Masseter contraction = normal response

- Palpation: TOP (tenderness on palpation) and muscle spasms found in sternocleidomastoid, upper fiber trapezius, and scalenes (anterior, middle, and posterior).Outcome Measures:

- NPRS for left facial pain:

- At rest (between attacks): 0/10

- During TN attack: 9-10/10

- Penn Facial Pain Scale (Penn-FPS):[10]

- 7 point scale with each item rated on a 0-10 NPRS, 0 = does not interfere to 10 = completely interferes

- Touching your face (including grooming): 7/10

- Brushing or flossing your teeth: 7/10

- Smiling or laughing: 3/10

- Talking: 9/10

- Opening your mouth widely: 3/10

- Eating hard foods like apples: 8/10

- 7 point scale with each item rated on a 0-10 NPRS, 0 = does not interfere to 10 = completely interferes

- 36- item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36):

- 20/36[11]

Clinical Impression[edit | edit source]

The patient is a 35 year old female diagnosed with CTN. The neurologist report indicates that the patient meets The International Headache Society criteria for TN[6]. Her subjective interview indicated that her symptoms are impairing her functional status; especially in terms of her occupational duties. She also has a history of anxiety which has been exacerbated by her prognosis. The MRI report was examined prior to the patient's initial assessment and indicates a neurovascular pathology which is characteristic of CTN. Clinical findings from the objective assessment are consistent with the diagnosis of CTN as symptoms were provoked with sensation testing. Reflex testing elicited normal response which is also indicative of CTN as abnormal responses are significantly correlated with Secondary Trigeminal Neuralgia (STN)[8].

Self-report pain measures revealed that the patient has severe pain and moderate irritability triggered by certain activities. The Penn-FPS scores demonstrate that the patient’s pain is negatively impacting her activities of daily life, occupation, and quality of life.

Ms. R, who received a recent diagnosis of CTN, is otherwise generally healthy and lives an active lifestyle. However, her symptoms are interfering with her daily activities as well as her occupation. She is also experiencing increased anxiety due to the uncertainty of her current prognosis. Ms. R is a good candidate for physiotherapy treatment with the involvement of other healthcare professionals to manage her symptoms and increase her functional capacity.

Problem List

Based on the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF):[edit | edit source]

| Body Structure and Function | Unilateral left facial pain

Anxiety Abnormal sensations (left side of face) |

| Activity | Eating (increased pain with harder foods)

Applying make-up Impaired talking ability |

| Participation | Occupational duties impacted

Social isolation due to fear of pan |

Intervention[edit | edit source]

Treatment Goals[edit | edit source]

Short Term Goals:

- Ms. R will be able to eat a full meal (non-hard foods) with reduced pain (NPRS <4/10) by the end of week 2 of treatment.

- Ms. R. will decrease the number of painful episodes (neural attacks), <7 attacks/day (NPRS <9) by the end of week 3 of treatment.

- Ms. R. will be able to talk for 10 minutes with reduced pain (NPRS <6/10) by the end of week 3 of treatment.

- Ms. R will be able to brush and floss her teeth with reduced pain (NPRS <4/10) by the end of week 3.

- Ms. R will be able to attend one social outing for at least 30 minutes after 2 weeks of treatment.

Long Term Goals:

- Ms. R will be able to touch her face (grooming and make-up) with decreased pain (NPRS <3/10) by the end of week 6.

- Ms. R will increase her SF-36 score to at least a 30/36 after 7 weeks of treatment.

- Ms. R will be able to eat a full meal including hard foods (i.e. apples) with reduced pain (NPRS <3/10) by the end of week 8.

- Ms. R will be able to complete a full work day of news reports with reduced pain (NPRS <3/10) by the end of week 8.

- Ms. R. will decrease the number of painful episodes (neural attacks), <5 attacks/day (NPRS <5) by the end of week 8 of treatment.

Management Program:[edit | edit source]

Physiotherapy Treatment Program:

| Treatment (Type) | Frequency | Intensity | Time |

Manual Therapy - Massage[12]

|

3 times per week | As tolerated | 15 minutes per treatment |

| Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (TENS)[12] | Daily or as needed. | 150Hz

50 μs Intensity set to the patient's sensory threshold. |

20 minutes per treatment |

| Ultrasound[12] | 3 times per week | Intensity: 0.5 w/cm2

Pulse ration: 50% Frequency: 1MHz |

8 minutes per treatment |

Manual Therapy:

Massage therapy for the patient’s upper fiber trapezius, scalene and sternocleidomastoid was selected because the patient reported tenderness on palpation for these muscles on the left side of her neck. The purpose of this treatment was to relax muscle fibers, reduce muscle spasms, and decrease the patient’s pain[12].

Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (TENS):

TENS was implemented for pain relief. One electrode is placed anterior to the ear while the second electrode is located near the end of the desired nerve branch (ophthalmic, maxillary and mandibular) . Electrode placement was adjusted to maximize pain relief when necessary[12][13].

Ultrasound:

Ultrasound, applied anterior to the opening of the ear canal and following along the three branches of the trigeminal nerve was used to help alleviate the patient’s pain. Placement was adjusted to maximize pain relief[12].

Self Management Strategies:

| Treatment (Type) | Frequency | Intensity | Time |

| Deep Breathing[13] | Daily | Relaxed breathing | 10 minutes |

| Distraction (e.g. imagery)[13] | Daily or as needed | N/A | As needed |

| Desensitization Program:

soft cloth on patient's affected left side[14] |

Daily | N/A | 15 minutes |

Trigeminal neuralgia is a very painful condition that can have profound negative effects on one's quality of life. For this reason the self-management strategies (1) deep breathing, (2) distraction, and (3) desensitization were implemented into the treatment program to assist the patient in coping with their pain and anxiety. Deep breathing was provided to decrease anxiety levels[13]. Distraction (imagery) helped the patient divert her attention away from her pain and improve her overall mood[13]. In addition, the desensitization program aims to promote habituation of the nervous system to a constant sensory stimulus[14].

Outcome[edit | edit source]

After 8 Weeks of Physiotherapy Treatment[edit | edit source]

- Sensation Testing:[9]

- Light touch testing: patients still reports severe, sharp pain in trigeminal branch distribution on the left side of her face.

- Sharp/dull testing: patients still reports severe, sharp pain in trigeminal branch distribution on the left side of her face.

- Palpation: absent TOP and muscle spasm found in sternocleidomastoid, upper fiber trapezius, and scalenes (anterior, middle, and posterior).

- Numeric Pain Rating Scale (NPRS) for left facial pain:

- At rest (between attacks) : 0/10

- During CTN attack: 7/10

- Penn Facial Pain Scale (Penn-FPS):[10]

- 0-10 NPRS, does not interfere to completely interferes

- Eating a meal: 4/10

- Touching your face (including grooming): 5/10

- Brushing or flossing your teeth: 5/10

- Smiling or laughing: 2/10

- Talking: 7/10

- Opening your mouth widely: 2/10

- Eating hard foods like apples: 6/10

- 0-10 NPRS, does not interfere to completely interferes

- 36- item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36):

- 28/36[11]

Referrals[edit | edit source]

Ms. R presents with multiple yellow flags (anxiety due to her debilitating pain and lack of social support), making her a suitable candidate for referral to a psychologist. The psychologist will work alongside other members of Ms. R’s healthcare team to integrate Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT) into the treatment program[15]. Moreover, they can work with Ms. R to change her negative thoughts, beliefs and attitudes about her condition while providing her with coping strategies to manage her anxiety and pain. In collaboration with a physiotherapist and other members of the healthcare team, a psychologist will help to set goals that are functional and meaningful[15]. This will provide Ms. R with strategies she can implement to track her progress during her road to recovery. Additionally, she will benefit greatly from restructuring how she thinks about her pain. Cognitive restructuring, implemented by a psychologist can help to decrease her pain intensity and increase her pain tolerance[15].

After receiving 2 months of physiotherapy treatment, Ms. R’s pain symptoms were slightly reduced; however, she did not progress to achieve the originally planned short-term and long-term treatment goals. Failure to accomplish these goals is a sign that physiotherapy treatment may not be sufficient to reduce her pain to a desirable level. For this reason, Ms. R will be referred back to her neurologist for an additional consultation. In collaboration with the other members of Ms. R’s healthcare team the neurologist will determine whether to continue with conservative treatment or refer her to a neurosurgeon for surgical interventions. There are numerous surgical techniques that the neurosurgeon may choose to treat Ms. R’s condition. The most common surgical procedures that are used to treat CTN are microvascular decompression (removal of a blood vessel compressing the trigeminal nerve), percutaneous rhizotomy (surgical compression of trigeminal nerve root to disrupt the pain causing pathway), and stereotactic radiosurgery (radiation therapy) [16].

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Available from: https://www.ninds.nih.gov/Disorders/Patient-Caregiver-Education/Fact-Sheets/Trigeminal-Neuralgia-Fact-Sheet (Accessed 10 May 2021).

- ↑ Eller JL, Raslan AM, Burchiel KJ. Trigeminal neuralgia: definition and classification. Neurosurgical focus. 2005 May 1;18(5):1-3.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Patten J. Trigeminal neuralgia. In: Neurological Differential Diagnosis. 2nd ed. London: Springer;1996:373-5.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Nurmikko TJ, Eldridge PR. Trigeminal neuralgia—pathophysiology, diagnosis and current treatment. British journal of anaesthesia. 2001 Jul 1;87(1):117-32.

- ↑ Reeta, Kumar U, Kumar V, Alam M, Islami D, Lal W et al. A Survey to Observe the Commonly Used Treatment Protocol for Trigeminal Neuralgia by Physiotherapist. International Journal of Physiotherapy. 2016;3(5):643-646

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 The International Classification of Headache Disorders: 2nd edition. Cephalalgia. 2004;24 Suppl 1:9-160

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Al-Quliti KW. Update on neuropathic pain treatment for trigeminal neuralgia: The pharmacological and surgical options. Neurosciences. 2015 Apr;20(2):107.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 Cruccu G, Finnerup NB, Jensen TS, Scholz J, Sindou M, Svensson P, Treede RD, Zakrzewska JM, Nurmikko T. Trigeminal neuralgia: new classification and diagnostic grading for practice and research. Neurology. 2016 Jul 12;87(2):220-8.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Lundy-Ekman L. Neuroscience-E-Book: Fundamentals for Rehabilitation. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2013 Aug 7.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Symonds T, Randall JA, Hoffman DL, Zakrzewska JM, Gehringer W, Lee JY. Measuring the impact of trigeminal neuralgia pain: the Penn Facial Pain Scale-Revised. Journal of pain research. 2018;11:1067.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Ware Jr JE, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36): I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Medical care. 1992 Jun 1:473-83.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 Zamani S, Okhovatian F. Physiotherapy Approach in Treatment of Trigeminal Neuralgia: A Case Report. Journal of Clinical Physiotherapy Research. 2018;3(1):42-7

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 Khanal D, Khatri SM, Anap D. Is there Any Role of Physiotherapy in Fothergill's Disease?. Journal of Yoga & Physical Therapy. 2014 Apr 1;4(2):1.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Myers CD, White BA, Heft MW. A review of complementary and alternative medicine use for treating chronic facial pain. The Journal of the American Dental Association. 2002 Sep 1;133(9):1189-96.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Johansson C, Dahl J, Jannert M, Melin L, Andersson G. Effects of a cognitive-behavioral pain-management program. Behaviour research and therapy. 1998 Oct 1;36(10):915-30.

- ↑ Wang DD, Ouyang D, Englot DJ, Rolston JD, Molinaro AM, Ward M, Chang EF. Trends in surgical treatment for trigeminal neuralgia in the United States of America from 1988 to 2008. Journal of Clinical Neuroscience. 2013 Nov 1;20(11):1538-45.