Tackling Overprescription

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Older people often benefit from interventional and preventative health care as this age bracket are greatest risk of multimorbidity. Unfortunately they are also at greatest risk of being treated unnecessarily for conditions that may never advance or cause symptoms. This form of health care can result in harm from use of more medicines than clinically necessary, that is overprescription of medicines.[1]

Problematic polypharmacy is generally seen as the result of a cascade of prescribing [2]. This cascade, often initiated when an adverse drug effect is misinterpreted as a new medical problem, leads to the prescribing of more medication to treat the initial drug-induced symptom(s). Potentially inappropriate medications (medications which should be avoided in older adults and those with certain health conditions), are also increasingly probable to be prescribed in the setting of problematic polypharmacy [2][3].

Deprescribing[edit | edit source]

Deprescribing is aplanned and supervised process of dose reduction or stopping of medication that may be causing harm, or are no longer beneficial. Deprescribing should be part of good prescribing, re-evaluating dosages periodically. Desprescription involves health care professional direction and supervision with the same level of expertise and attention that prescribing entails [4].

- According to research, there are high levels of inappropriate medication use in older adults across a variety of settings and countries, proposing that there are currently vast unrealized opportunities of deprescribing [5][6].

- Research suggests that older individuals and health professionals are “eager” to undertake deprescribing [7].

Factors that contribute to successful deprescribing include significant provider effort (best if in collaboration with interdisciplinary team members.

Certain medication classes can successfully be deprescribed eg vitamins, minerals, analgesics, and proton pump whereas antipsychotic agents, antidepressants, and ophthalmic preparations, prescribed by specialists, are more difficult to deprescribe. [8]

When Deprescribing medication(s), patients’ should be provided with sufficient knowledge of the decision to be made, have realistic expectations for outcomes and be confident in their decision [9]. Evidence suggests that patients are more willing to have a medication deprescribed if it is recommended by a health professional whom they have a relationship with [10][11][12]. The health professionals elucidated in the studies were physicians, GPs and medical specialists. Research indicates that multidisciplinary interventions are generally the most effective at reducing polypharmacy and inappropriate medication use [4][13].

The following videos provides an easy to follow in-depth discussion regarding the concept (6 minutes)

The Potential Role of the Physiotherapist in Deprescribing[edit | edit source]

Available literature linking physiotherapy with deprescribing has focused only on the role of physiotherapy as a supplementary treatment for pain relief when reducing opioid dosage.

Other non-pharmacological (only with doctors input) interventions to help with deprescribing include:

- Encouraging low-salt diets and exercise to reduce prescription of antihypertensives,

- Psychotherapy and changing sleep habits to reduce or avoid prescription of antidepressants,

- Pain management and rehabilitation through physiotherapy. Literature linking physiotherapy with deprescribing has focused on the role of physiotherapy as a supplementary treatment for pain relief when reducing opioid dosage. Opioid-dose reduction can be supplemented by interdisciplinary rehabilitation programs, including physiotherapy, cognitive behavioural therapy and occupational therapy, research showeding long-term improvements in pain, functioning and emotional health [14][15][16]. In addition, guidelines for opioid use recommend that patients with long term complex pain should have their opioid dosage regularly reviewed, with removal or reduction of opioids supplemented with non-opioid analgesics or non-drug treatments such as physiotherapy, where appropriate [17][18].

Current non- Prescribers expected knowledge and skills of medication:[edit | edit source]

The majority of physiotherapists should be able to signpost patients to where they could obtain appropriate medication advice[19].

General and Specific advice that non-prescribers can give:[edit | edit source]

General advice that can apply to the whole population may be given on the effects of medication. For example the general side effects of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). While providing advice it should also be recommended that the patient should seek advice from a pharmacist or independent prescriber before altering any medication they currently take[21].

According to the CSP, specific advice may be given to patients in certain situations, for example:

“It would be acceptable for a physiotherapist to recommend taking paracetamol as a simple analgesic for musculoskeletal pain, as the evidence for this intervention is widespread e.g. there is a NICE guideline on the matter. Also, paracetamol is on the General Sales List (GSL) and available without supervision from an independent prescriber or pharmacist.”[21]

Physiotherapists can recommend patients to go and seek a specific medication from their GP. ONLY IF the physiotherapists have substantial knowledge of the prescription only medication, the evidence base behind it and is working with that particular relevant patient group. If the medication is advised it MUST be followed up with the recommendation that it must be discussed with their GP [19][21].

Patient taking their medication incorrectly? Advice non-prescribers can give:[edit | edit source]

If a non-prescriber physiotherapist notices a patient is not taking their medication correctly, they can refer the patient to the medications instructions and remind them how and when/ dose they should be taking their medication as prescribed[21]. This can also apply to medication devices, e.g. an inhaler, advice can be given how to use it according to guidelines. Expected adverse effects of medication? What non-prescribers can do: Physiotherapists can refer the patient back to the GP/pharmacists or can contact the GP directly providing information on their concerns [22].

Knowledge on Side effects and possible drug interactions[edit | edit source]

Table (1) illustrates a limitedlist of the commonly prescribed medications physiotherapists may encounter with their patients, and the side effects that can occur as a result. It is important that physiotherapists are aware of these, and other common medication side effects to be able to identify these issues as they arise.

Table (1): Common medications encountered by physiotherapists and their common side effects[22][23] [24] [25]

| Type of Medication | Purpose of Medication | Side-Effects | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) | Analgesia- reduce pain, inflammation | Dizziness, headache, renal impairment, gastrointestinal toxicity ulcers and/or bleeding and increased risk of cardiovascular side effects | High dose aspirin, celecoxib, diclofenac, ibuprofen, indometacin |

| Diuretics | High blood pressure (hypertension), fluid retention because of heart failure, fluid build up in the abdomen caused by liver damage | Dizziness, headaches, increased blood sugar, muscle cramps, nausea, increase frequency to urinate | Furosemide, bumetanide, torsemide, Edecrin |

| Opioid analgesics | Moderate to severe pain | Constipation, drowsiness, confusion, delirium, nausea, dizziness | Codeine, tramadol morphine

Can combine with NSAIDs |

| Anticoagulants | High risk of blood clots- Atrial fibrillation, stroke, Myocardial infarction, DVT, pulmonary embolism. | Excessive bleeding, Dizziness, weakness, severe stomach and headache | Heparin, warfarin, rivaroxaban, dabigatran, apixabanm, edoxaban |

| Beta blockers | Hypertension, angina, some abnormal heart rhythms (e.g. AF), Myocardial infarction, glaucoma, overactive thyroid symptoms | Dizziness, weakness, drowsiness, fatigue, cold hands and feet, dry mouth, skin, or eyes, headache, upset stomach, constipation, blurred vision, slowed heart rate | Atenolol, bisoprolol, cardicor, carvedilol, metoprolol, nebivolol, propranolol |

| Angiotensin receptor blockers | Hypertension, heart failure | Dizziness, headaches, cold or flu-like symptoms, muscle weakness/ cramps | Candesartan, irbesartan, losartan, valsartan, olmesartan |

| Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE) | Heart failure, hypertension | Dry cough, headaches, dizziness, hyperkalemia, hypotension | Enalapril, lisinopril, perindopril, ramipril |

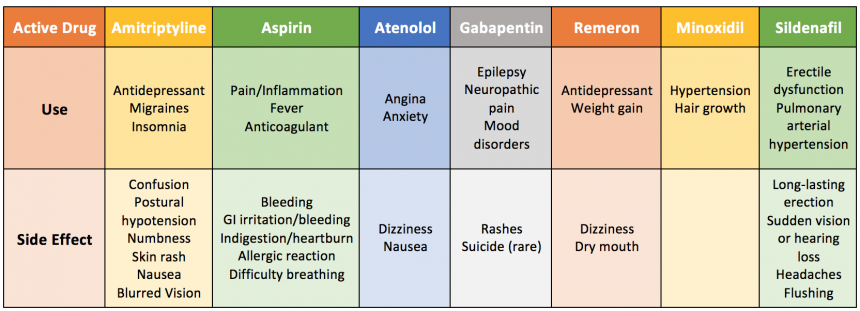

Table (2) demonstrates a limited list of medications that are “multi-purposeful”, meaning they can target and treat more than one issue. It is important to be aware of these medications and not to assume the patient has been prescribed the medication for the most common reason. It is also valuable to be aware of these medications for if a patient has more than one complication, it may be possible to suggest prescription of 1 medication to treat both issues, rather than 2 medications with 2 possible lists of side effects.

Table (2): Examples of Repurposing Drugs[22][26]

Table (3): Most Common Medications that result in falls [30]

| Types of Medication | Purpose | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Hypnotics and Sedatives | Insomnia- induce sleep | zaleplon, zolpidem, zopiclone |

| Antidepressants | Treat depression, anxiety, PTSD, OCD | Fluoxetine, citalopram, paroxetine, sertraline, duloxetine, venlafaxine, amitriptyline, clomipramine, imipramine |

| Benzodiazepines | Severe anxiety, insomnia, seizures | Diazepam, lorazepam, chlordiazepoxide, oxazepam, temazepam, nitrazepam, loprazolam, lormetazepam, clobazam |

Table (3) illustrates medications that are highly correlated with falls. If a patient is becoming greatly affected by this falls side effect and is subsequently jeopardising their safety, cessation or alteration of dose may be proposed. As a non-prescriber, this can be discussed with the patient’s GP who has the authority to make such changes[21]. Physiotherapy interventions can be suggested in conjunction with the medication alteration to target the falls risk, or as a substitute to the purpose of the medication.

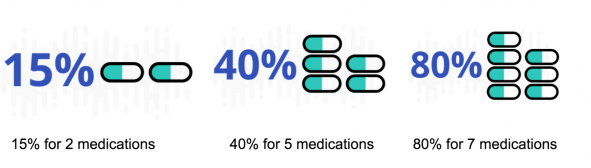

The more medications a patient takes, the risk is increased of the drugs interacting with each other [26].

Here is an easy guide video on information regarding drug interactions[31]:

Common Populations at Risk[edit | edit source]

The use of multiple drugs is not always an indicator of poor drug treatment or overmedication[32]. Appropriate medication depends on whether or not the advantages outweigh the disadvantages which is subjective to both the individual and their given condition(s). It can be very hard to predict the side-effects or clinical effects of a drug combination without testing it on the specific individual as the effects all very based on the individual's genome-specific pharmocokinetics[32]. At risk populations include:

- Elderly Populations

- Psychiatric Patients

- Multimorbidity

- Recent hospitalizations/major surgery

- People seeing multiple doctors

- Terminally ill patients

Non-Pharmacological Interventions[edit | edit source]

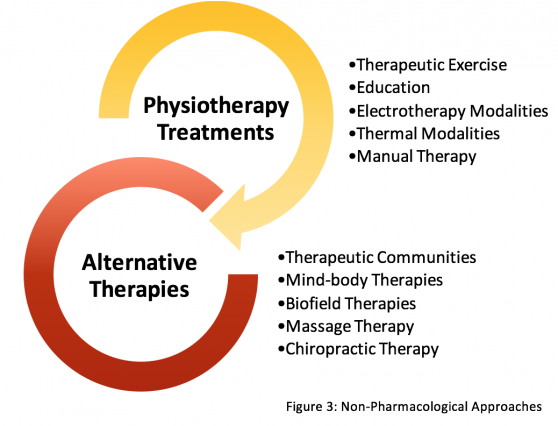

The use of non-pharmacological options in tackling overprescription should be considered across all allied health professionals. For physiotherapists, the vast majority of interventions utilized in practice are non-pharmacological as most clinicians are non-prescribers. It is important for physiotherapists and other relevant health care providers to be aware of the wide array of treatment options for sufficient provision of holistic patient care, to be used on their own or in conjunction with drug therapies, in effort to address clinical scenarios where overprescription may be an issue. The most common treatment for chronic pain is traditionally pharmacological[33]. Health care professionals should be aware of the benefits of non-pharmacological options with sufficient evidence bases for a range of relevant domains such as improvements in pain and functional status, as well as cognitive and emotional states.

A recent 2017 study has discovered barriers to non-pharmacological options with regards to chronic pain[34]. Top ranked patient-reported barriers included high cost, transportation problems, and low motivation. While top provider-reported barriers include scepticism about efficacy of the non-pharmacological options[34]. For this reason, the authors of this Physiopedia page have constructed a non-exhaustive list of common Non-Pharmacological Approaches, accompanied with descriptions and mechanisms of the interventions, brief summary of the evidence base, and suggestions for referrals and signposting patients for options outside the scope of physiotherapy. Some of these options listed are covered under the National Health Service, others can be used for self-management, and some address beliefs and cognitive effects. Therefore, this resource should be used in hopes to address the high cost, transportation, and low motivation barriers of patients, while providing a brief population dependent evidence base for a wide array of non-pharmacological options so healthcare providers can be confident in their choice of treatment option in accordance with the individual values of their patient[34].

The decision to seek non-pharmacological options outside conventional care, should be discussed with a patient’s general practitioner or wider multidisciplinary team, and include patient preferences and values, in order to provide safe and optimal patient-centred care. Non-Pharmacological approaches are listed for both inside and outside the scope of physiotherapy (Figure 3).

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Page A, Etherton-Beer C. Undiagnosing to prevent overprescribing. Maturitas. 2019 May 1;123:67-72. Available:https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0378512219300726#preview-section-introduction (accessed 28.12.2022)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 McGrath K, Hajjar E.R, Kumar C, Hwang C, Salzman B. Deprescribing: A simple method for reducing polypharmacy. The Journal of Family Practice 2017;66:436-445

- ↑ Steinman M.A, Landefeld C.A, Rosenthal G.E, Berthenthal D, Sen S, Kaboli P.J. Polypharmacy and prescribing quality in older people. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 2006;54:1516-1523

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Reeve E, Thompson W, Farrell B. Deprescribing: A narrative review of the evidence and practical recommendations for recognizing opportunities and taking action. European Journal of Internal Medicine.2017;38:3-11.

- ↑ Morin L, Laroche M.L, Texier G, Johnell K. Prevalence of potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults living in nursing homes: A systematic review. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association 2016;17:862

- ↑ Todd A, Husband A, Andrew I, Pearson, S.A, Lindsey L, Holmes H. Inappropriate prescribing of preventative medication in patients with life-limiting illness: a systematic review. BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care 2017;7: 113–121.

- ↑ Sirois C, Oullet N, Reeve E. Community-dwelling older people’s attitudes towards deprescribing in Canada. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy 2017;13:864-870.

- ↑ Dharmarajan TS, Choi H, Hossain N, Munasinghe U, Lakhi F, Lourdusamy D, Onuoha S, Murakonda P, Skokowska-Lebelt A, Kanagala M, Russell RO. Deprescribing as a clinical improvement focus. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2020 Mar 1;21(3):355-60.Available:https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31672564/ (accessed 28.12.2022)

- ↑ Stacey D, Légaré F, Col N.F, Bennett C.L, Barry M.J, Eden K.B, Holmes-rovner M, Llewellyn-thomas H, Lyddiatt A, Thomson R, Trevena L, Wu J.H Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2014;28

- ↑ Reeve E, To J, Hendrix I, Shakib S, Roberts M.S, Wiese M.D. Patient barriers to and enablers of deprescribing: a systematic review. Drugs Aging 2013;30:793–807.

- ↑ Linsky A, Simon S.R, Bokhour B. Patient perceptions of proactive medication discontinuation. Patient Education and Counseling 2015;98:220–225.

- ↑ Reeve E, Low L.F, Hilmer S.N. Beliefs and attitudes of older adults and carers about deprescribing of medications. British Journal of General Practice 2016;66:552–60.

- ↑ Kaur S, Mitchell G, Vitetta L, Roberts M.S. Interventions that can reduce inappropriate prescribing in the elderly: a systematic review. Drugs Aging 2009;26:1013–28

- ↑ Townsend C.O, Kerkvliet J.L, Bruce B.K, Rome J.D, Hooten W.M, Luedtke C.A, Hodgson J.E. A longitudinal study of the efficacy of a comprehensive pain rehabilitation program with opioid withdrawal: Comparison of treatment outcomes based on opioid use status at admission. Pain 2008;140:177-189.

- ↑ Huffman K.L, Sweis G.W, Gase A, Scheman J, Covington E.C. Opioid Use 12 Months Following Interdisciplinary Pain Rehabilitation with Weaning. Pain Medicine 2013;14:1908-1917.

- ↑ Hooten W.M, Townsend C.O, Sletten C.D, Bruce B.K, Rome J.D. Treatment Outcomes after Multidisciplinary Pain Rehabilitation with Analgesic Medication Withdrawal for Patients with Fibromyalgia. Pain Medicine 2007;8:8-16.

- ↑ Kahan M, Mailis-gagnon A, Wilson L, Srivastava A. Canadian guideline for safe and effective use of opioids for chronic noncancer pain Clinical summary for family physicians. Part 1: general population. Canadian Family Physician 2011;57:1257-1266.

- ↑ Berna C, Kulich R.J, Rathmell J.P. Tapering Long-term Opioid Therapy in Chronic Noncancer Pain: Evidence and Recommendations for Everyday Practice. Mayo Clinic Proceedings 2015;90:828-842

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Chartered Society of Physiotherapy. Practice Guidance for Physiotherapist Supplementary and/or Independent Prescribers in the safe use of medicines. [Internet]. London: CSP; 2016. Available from: http://www.csp.org.uk/publications/practice-guidance-physiotherapist-supplementary-prescribers

- ↑ Youtube. What is Pharmacokinetics? - A simple Introduction! [Internet]. 2017 [cited 15 April 2018]. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=caoCN-J5FEE

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 21.4 Chartered Society of Physiotherapy. Medicines, prescribing and physiotherapy [Internet]. CSP; 2016. Available from: http://www.csp.org.uk/publications/medicines-prescribing-physiotherapy-4th-edition

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 Reznik J, Keren O, Morris J, Biran I. Pharmacology Handbook for Physiotherapists. Australia: Elsevier; 2016.

- ↑ Side effects [Internet]. NHS choices. 2018 [cited 15 April 2018]. Available from: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/anticoagulants/side-effects/

- ↑ Antidepressants [Internet]. NHS choices. 2018 [cited 15 April 2018]. Available from: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/antidepressants/

- ↑ Beta-blockers [Internet]. NHS choices. 2018. Available from: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/beta-blockers/

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Silvestrini E. Drug Interactions [Internet]. DrugWatch. 2018 [cited 15 April 2018]. Available from: https://www.drugwatch.com/drug-interactions/

- ↑ Babyak M, Blumenthal J, Herman S, Khatri P, Doraiswamy M, Moore K et al. Exercise Treatment for Major Depression: Maintenance of Therapeutic Benefit at 10 Months. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2000;62(5):633-638.

- ↑ Blake H. Physical activity and exercise in the treatment of depression. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2012;3.

- ↑ Blumenthal J, Smith P, Hoffman B. Is Exercise a Viable Treatment for Depression?. ACSM's Health & Fitness Journal. 2012;16(4):14-21.

- ↑ Ruxton K, Woodman R, Mangoni, A. Drugs with anticholinergic effects and cognitive impairment, falls and all‐cause mortality in older adults: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 2015; 80(2):209-220.

- ↑ Youtube. Drug interaction episode 1 [Internet]. 2015 [cited 15 April 2018]. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vpoR1OiTOyU

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Tamminga C. When Is Polypharmacy an Advantage?. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2011;168(7):663-663.

- ↑ Nalamachu S. An overview of pain management: the clinical efficacy and value of treatment. American journal of managed care 2013;19:261-266

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 Becker W.C, Dorflinger L, Edmond S.N, Islam L, Heapy A.A, Fraenkel L. Barriers and facilitators to use of non-pharmacological treatments in chronic pain. BMC Family Practice 2017;18 [online] [viewed 18/04/2018]. Available from: http://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-017-0608-2.