Spondyloarthropathy--AS: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 166: | Line 166: | ||

== Case Reports/ Case Studies == | == Case Reports/ Case Studies == | ||

'''[http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=Ankylosing+spondylitis+in+a+patient+referred+to+physical+therapy+with+low+back+pain Ankylosing Spondylitis in a Patient referred to Physical Therapy with Low Back Pain] '''by Gretchen Seif & James Elliott<br>January 2012 | '''[http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=Ankylosing+spondylitis+in+a+patient+referred+to+physical+therapy+with+low+back+pain Ankylosing Spondylitis in a Patient referred to Physical Therapy with Low Back Pain] '''by Gretchen Seif & James Elliott<br>January 2012 | ||

[http://www.jospt.org/issues/id.2788/article_detail.asp '''Differential Diagnosis and Management of Ankyosing Spondylitis Masked as Adhesive Capsulitis: A Resident’s Case Problem.''']by Jordan CL, Rhon DI'''<ref>ordan CL, Rhon DI. Differential Diagnosis and Management of Ankyosing Spondylitis Masked as Adhesive Capsulitis: A Resident’s Case Problem. J Orthop Sport Phys. 2012;42(10):842-852.</ref> '''<br> | [http://www.jospt.org/issues/id.2788/article_detail.asp '''Differential Diagnosis and Management of Ankyosing Spondylitis Masked as Adhesive Capsulitis: A Resident’s Case Problem.''']by Jordan CL, Rhon DI'''<ref>ordan CL, Rhon DI. Differential Diagnosis and Management of Ankyosing Spondylitis Masked as Adhesive Capsulitis: A Resident’s Case Problem. J Orthop Sport Phys. 2012;42(10):842-852.</ref> '''<br> | ||

[https://my.usa.edu/ICS/icsfs/Ankylosing_Spondylitis_Radiographs.ppt?target=aa7d4134-1918-4e5b-938c-e296dccefdc9 Link to PowerPoint from Resident's Case Problem] | |||

<br> | |||

'''[http://www.sciencedirect.com/science?_ob=MImg&_imagekey=B6WBJ-4717YF1-C-1&_cdi=6712&_user=6406088&_pii=S1521694202902408&_origin=gateway&_coverDate=09%2F30%2F2002&_sk=999839995&view=c&wchp=dGLbVtz-zSkzk&md5=a9d7a9f48591a72f1c1e9a8406c5da67&ie=/sdarticle.pdf Spa and exercise treatment in ankylosing spondylitis: fact or fancy?]<ref name="Tubergen">Tubergen A, Hidding A. Spa and exercise treatment in ankylosing spondylitis: fact or fancy? Best Practive and Research Clinical Rheumatology. 2002; 16:4. 653-666.</ref>'''<br> | '''[http://www.sciencedirect.com/science?_ob=MImg&_imagekey=B6WBJ-4717YF1-C-1&_cdi=6712&_user=6406088&_pii=S1521694202902408&_origin=gateway&_coverDate=09%2F30%2F2002&_sk=999839995&view=c&wchp=dGLbVtz-zSkzk&md5=a9d7a9f48591a72f1c1e9a8406c5da67&ie=/sdarticle.pdf Spa and exercise treatment in ankylosing spondylitis: fact or fancy?]<ref name="Tubergen">Tubergen A, Hidding A. Spa and exercise treatment in ankylosing spondylitis: fact or fancy? Best Practive and Research Clinical Rheumatology. 2002; 16:4. 653-666.</ref>'''<br> | ||

Revision as of 21:35, 24 June 2013

Original Editors - Adam Bockey from Bellarmine University's Pathophysiology of Complex Patient Problems project.

Top Contributors - Adam Bockey, Elise Jespers, Elaine Lonnemann, Kim Jackson, Admin, WikiSysop, 127.0.0.1, Wendy Walker and Lucinda hampton - Elaine Lonnemann.

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

Spondyloarthropathy represents a group of noninfectious, inflammatory, rheumatic diseases that primarily includes ankylosing spondylitis, Reiter’s syndrome, reactive arthritis, and the arthritis associated with psoriasis and inflammatory bowel diseases. The primary pathologic sites are the sacroiliac joints, the bony insertions of the annulus fibrosis of the intervertebral discs, and the apophyseal joints of the spine.[1]

Ankylosing Spondylitis (AS) also known as Marie- Strumpell disease or bamboo spine, is an inflammatory arthropathy of the axial skeleton, usually involving the sacroiliac joints, apophyseal joints, costovertebral joints, and intervertebral disc articulations.[2] AS is a chronic progressing inflammatory disease that causes inflammation of the spinal joints that can lead to severe, chronic pain and discomfort. In advanced stages, the inflammation can lead to new bone formation of the spine, causing the spine to fuse in a fixed position often creating a forward stooped posture.[3]

Prevalence[edit | edit source]

Ankylosing Spondylitis is 3 times more common in men than in women and most often begins between the ages of 20-40.[5] Recent studies have shown that AS may be just as prevalent in women, but diagnosed less often because of a milder disease course with fewer spinal problems and more involvement of joints such as the knees and ankles. Prevalance of AS is nearly 2 million people or 0.1% to 0.2% of the general population in the United States. It occurs more often in Caucasions and some Native American than in African Americans, Asians, or other nonwhite groups.[1] AS is 10 to 20 times more common with first degree relatives of AS patients than in the general population. The risk of AS in first degree relatives with the HLA-B27 allele is about 20% occurrence.[5]

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation [edit | edit source]

The initial presenting complaints of AS is non-traumatic, insidious onset of low back, buttock, or hip pain and stiffness for more than 3 months in a person, usually male under 40 years of age.[1] It is usually worse in the morning lasting more than 1 hour and is described as a dull ache that is poorly localized, but it can be intermittently sharp or jolting. Overtime pain can become severe and constant and coughing, sneezing, and twisting motions may worsen the pain. Pain may radiate to the thighs, but does not typically go below the knee. Buttock pain is often unilateral, but may alternate from side to side.[2] Paravertebral muscle spasm, aching, and stiffness are common making sacrioliac areas and spinous process very tender upon palpation.[1] A flexed posture eases the back pain and paraspinal muscle spasm; therefore, kyphosis is common in untreated patients.[5] Enthesitis (inflammation of tendons, ligaments, and capsular attachments to bone) may cause pain or stiffness and restriction of mobility in the axial skeleton.[2] A positive Schober test is used to confirm reduction in spinal motion which is associated with AS. Since AS is a systemic disease an intermittent low grade fever, fatigue, or weight loss can occur.[1] In advanced stages the spine can become fused and a loss of normal lordosis with accompanying increased kyphosis of the thoracic spine, painful limitations of cervical joint motion, and loss of spine flexibility in all planes of motion. A decrease in chest wall excursion less than 2 cm could be an indicator of AS because chest wall excursion is an indicator of decreased axial skeleton mobility.[2]

In a recent review, four out of five positive responses to the following questions may help with the determining of AS:

1. Did the back discomfort begin before age 40

2. Did the discomfort begin slowly

3. Has the discomfort persisted for 3 months

4. Was morning stiffness a problem

5. Did the discomfort improve with exercise

Specificity= 0.82, Sensitivity =0.23

LR for four out of five positive responses = 1.3[6]

Associated Co-Morbidities[edit | edit source]

Uveitis, conjunctivitis, or iritis occurs in nearly 25% of the people with AS.[1] Signs of iritis or uveitis are: eye(s) becoming painful, watery, red, and sometimes blurred vision or sensitivity to bright light.[3] Pulmonary changes such as chronic infiltrative or fibrotic bullous changes of the upper lobe occur in 1% to 3% of the people with AS.[1] Cardiomegaly, conduction defects, and pericarditis are all common complications of AS.[8] Also many people with AS experience bowel inflammation, which can be associated with Crohn’s Disease or ulcerative colitis.[3]

Medications[edit | edit source]

NSAIDs (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) reduce pain and suppress joint inflammation and muscle spasm, in return increasing range of motion.[8] NSAIDs can cause significant side effects, in particular, damage to the gastrointestinal tract.[3] In some cases disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDS) such as methotrexate (MTX) or sulfasalazine (SSZ) may be used for peripheral disease.[2] Corticosteroid injections into the sacroiliac joints may help severe sacroiliitis. Topical corticosteroids can also be used for acute uveitis or iritis.[8] The most recent medication for AS are the biologics or TNF Blockers. These agents have been shown effective in preventing the progression of AS by reducing disease activity, decreasing inflammation, and improving spinal mobility.[2]

Examples of TNF blockers include: [9]

- Adalimumab (Humira)

- Etanercept (Enbrel)

- Infliximab (Remicade)

- Golimumab (Simponi)

Diagnostic Tests/Lab Tests/Lab Values[edit | edit source]

AS can be diagnosed by the modified New York criteria, the patient must have radiographic evidence of sacroiliitis and one of the following: (1) restriction of the lumbar spine motion in both the sagittal and frontal planes, (2) restriction of chest expansion (usually < 2.5 cm) (3) a history of back pain includes onset at <40 year, gradual onset, morning stiffness, improvement with activity, and duration >3 months.[8]

Imaging tests[9]

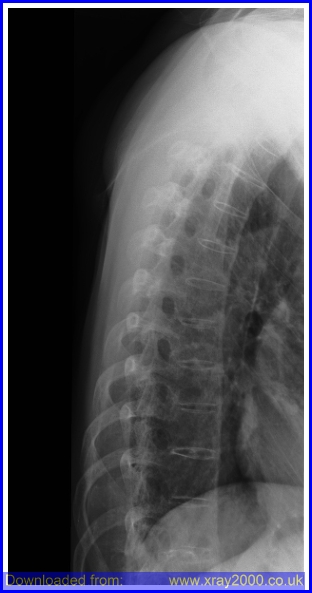

- X-rays. Radiographic findsing of symmetric, bilateral sacroiliitis include blurring of joint margins, extaarticular sclerosis, erosion, and joint space narrowing. As bony tissue bridges the vertebral bodies and posterior arches, the lumbar and thoracic spine creates a “bamboo spine” image on radiographs.[2]

- Computerized tomography (CT). CT scans combine X-ray views taken from many different angles into a cross-sectional image of internal structures. CT scans provide more detail, and more radiation exposure, than do plain X-rays.[9]

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Intraarticular inflammation, early cartilage changes and underlying bone marrow edema and osteitis can be seen using an MRI technique called short tau inversion recovery (STIR).[2] Using radio waves and a strong magnetic field, MRI scans are better at visualizing soft tissues such as cartilage.[9]

- Lab tests. There is no current laboratory testing in the diagnostic of AS, laboratory tests are primarily for ruling out other diseases. The presence of the HLA-B27 antigen is a useful adjunct to the diagnosis, but cannot be diagnostic alone.[2]

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

-Modified Health Assessment Questionnaire (MHAQ)

-and http://www.basdai.com/BASDAI.php Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI)

Etiology/Causes[edit | edit source]

AS is believed to be genetically inherited, and nearly 90% of people with AS are HLA-B27 positive.6 However, only 2% of the people with this antigen develop AS.[2] Additionally, 10% to 20% of people who have a first degree relative with AS and how inherit the HLA-B27 antigen eventually develop AS.[11] Recently, two more genes have been identified that are associated with AS. These genes, ARTS1 and IL23R, seem to play a role in influencing immune function.[12] The IL23R gene plays a role in the immune response to infection and making a receptor present on the surface of several types of immune system cells. The receptor is involved in triggering certain chemical signals inside the cell that promote inflammation and help coordinate the immune system's response to infection. It is already recognized as playing a role in a number of autoimmune diseases, such as Crohn's disease and psoriasis, which often are associated Co-morbidities.[13]

Systemic Involvement[11][edit | edit source]

-Neurologic involvement - Symptoms associated with spinal dislocations, subluxations, fractures, cauda equina syndrome

- Cardiovascular manifestations - Aortitis, aortic/mitral insufficiency, conduction defects

- Hip/shoulder involvement

- Chronic back stiffness and pain

Medical Management (current best evidence)[edit | edit source]

The primary medical focus with AS is to reduce inflammation and stiffness in the joints, maintain mobility and correct posture alignment, while relieving pain. NSAIDS or DMARDs are the most commonly medications used for joint pain and inflammation. For more progressive forms of AS surgery may be indicated; however, this may only be appropriate for individuals with sever deformities that impedes vision, ambulating, eating, chest excursion, or respiratory function. Other targeted therapies may be indicated to treat specific organ involvement, such as eye inflammation to avoid lifelong complications. [2] No treatment has been proven to prevent the progression of AS, but further research is needed. The key to maintaining comfort and spinal mobility is regular exercise. Intermittent physical therapy may be necessary to correct or minimize deformity or joint restrictions as well as to maintain motivation.[14]

Physical Therapy Management (current best evidence)[edit | edit source]

A multimodal physical therapy program including aerobic, stretching, education and pulmonary exercises in conjunction with routine medical management has been shown to produce greater improvements in spinal mobility, work capacity, and chest expansion compared with medical care alone.[2] Since the severity of AS is very different among individuals, there is no specific exercise program that showed the greatest improvements. Some studies showed that a 50 minute, three times a week multimodal exercise program showed significant improvements after 3 months in chest wall excursion, chin to chest distance, occiput to wall distance, and the modified Schober flexion test.[2]

EXERCISE:

A few recommended exercises for an individual with AS is to focus on breathing capacity should be evaluated and established. Stretching of the shortened muscles and chest expansion should be encouraged. Improving and maintaining cardiovascular fitness with aerobic exercise is also important. Strengthening of the hypomobile trunk extensors is also important to encourage an upright erect posture, so when spinal fusion occurs, the spine is aligned in the most functional position. Posture education can be a very important component to the patient to maintain an erect posture as well. Aquatic therapy can be an excellent option for most to provide low impact extension and rotation principles.[2]

Exercises that should be avoided include high impact and flexion exercises. Over exercising can be potentially harmful and could exacerbate the inflammatory process.[2]

MANUAL THERAPY

Some have advocated the efficacy and use of gentle non-thrust manipulation in the spine.[15]

COCHRANE REVIEW

In 2008 a Cochrane Review was published that reviewed the effectiveness of Physiotherapy Management in patients with AS. Below is the summary from Dagfinrud H, Hagen KB, and Kvien TK. [16]

| "Four studies compared individual or supervised exercises to no therapy at all. They found that both individual and supervised exercise programs improve spinal movement more than no therapy. The exercise programs were done for two to six months. Three studies compared home exercises to supervised group exercises. They found that group exercises improve movement in the spine and overall well-being, but did not improve self-reported physical function more than home exercises. Exercises were done for three weeks to nine months, and included strengthening, aerobic exercises, hydrotherapy, sports activities and stretching. One study compared two groups who both did weekly group exercises for 10 months, but one of the groups also went to a spa resort for three weeks of physiotherapy. Spa therapy plus weekly group exercises improves pain and overall well-being more than just weekly group exercises. One study compared balneotherapy and daily exercises with only daily exercises, and another study compared balneotherapy with fresh water therapy. Both these studies showed improvements after treatment for several outcomes, but no significant differences between the groups were found. One study compared a four-month experimental exercise program with a conventional program. Both groups improved, but the experimental exercise group improved more on spinal mobility and physical function than the conventional exercise group.” |

|

Physiotherapy or exercises are helpful to people with ankylosing spondylitis. |

Alternative/Holistic Management (current best evidence)

[edit | edit source]

Alternative or Holistic treatment for AS has no specific scientific evidence to show improvements, but some patients have benefited from the treatments such as acupuncture, Yoga, massage, & Oriental Medicine.[3]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Most Common differential diagnosis[2]

• Rheumatoid arthritis

• Psoriasis

• Reiter's syndrome

• Fracture

• Osteoarthritis

• Ulcerative colitis

• Crohn’s disease

Differential Diagnosis of Ankylosing Spondylitis and Thoracic Spinal Stenosis[17]

| Ankylosing Spondylitis | Thoracic Spinal Stenosis | |

| History | Morning stiffness Intermittent aching pain Male predominance Sharp pain/ach Bilateral scroiliac pain may refer to posterior thigh |

Intermittent aching pain Pain may refer to both legs with walking |

| Active movements | Restricted | May be normal |

| Passive movements | Restricted | May be normal |

| Resisted isometric movements | Normal | Normal |

| Special tests | None | Bicycle test of van Gelderen may be positive Stoop test may be positive |

| Reflexes | Normal | May be affected in long standing cases |

| Sensory deficit | None | Usually temporary |

| Diagnostic imaging | Plain films are diagnostic | Computed tomography scans are diagnostic |

In the early stages of ankylosing spondylitis,the changes in the sacroiliac joint are similar to that of rheumatoid arthritis, however the changes are almost always bilateral and symmetrical. This fact allows ankylosing spondylitis to be distinguished from psoriasis, Reiter's syndrome, and infection. Changes at the sacroiliac joint occur throughout the joint, but are predominantly found on the iliac side.

Case Reports/ Case Studies[edit | edit source]

Ankylosing Spondylitis in a Patient referred to Physical Therapy with Low Back Pain by Gretchen Seif & James Elliott

January 2012

Differential Diagnosis and Management of Ankyosing Spondylitis Masked as Adhesive Capsulitis: A Resident’s Case Problem.by Jordan CL, Rhon DI[18]

Link to PowerPoint from Resident's Case Problem

Spa and exercise treatment in ankylosing spondylitis: fact or fancy?[19]

Inflammatory Back Pain in Ankylosing SpondylitisResources[6]

Self- and manual mobilization improves spine mobility in men with ankylosing spondylitis – a randomized study[20]

Shoulder, Knee, and Hip Pain as Initial Symptoms of Juvenile Ankylosing Spondylitis: A Case Report[21]

Resources[edit | edit source]

Spondylitis Association of America[3]

Recent Related Research (from Pubmed)[edit | edit source]

see tutorial on Adding PubMed Feed

Extension:RSS -- Error: Not a valid URL: Feed goes here!!|charset=UTF-8|short|max=10

References[edit | edit source]

see adding references tutorial.

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 Goodman C, Snyder T. Differential Diagnosis for Physical Therapists: Screening for Referral. St. Louis, MO: Saunders Elsevier: 2007. 539

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 Goodman C, Fuller K. Pathology: Implications for the Physical Therapist. 3rd ed. St. Louis: Saunders Elsevier; 2009.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 Spondylitis Association of America. http://www.spondylitis.org/main.aspx. 2011. March 13, 2011.

- ↑ Vilke G. Areas of inflammation in ankylosing spondylitis. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2s8eueQ4-eM. Accessed on March 30, 2011

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Beers MH, et. al. eds. The Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy. 18th ed. Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck Research Laboratories; 2006.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Rudwaleit M, Metter A, Listing J, Sieper J, Braun J. Inflammatory back pain in ankylosing spondylitis; a reassessment of the clinical history for application as classification and diagnostic criteria. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2005; 54:2. 569-578.

- ↑ Health writings. Ankylosing spondylitis drug. http://www.health-writings.com/category/0/1/543/ Access March 30, 2011

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Beers MH, ed. The Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy, 18th edition. Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck and CO; 2006

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 Ankylosing Spondylitis. http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/ankylosing-spondylitis/DS00483. March 20, 2011.

- ↑ Jalbum, Chameleon. Spine-t ankylosing spondylitis. http://www.e-radiography.net/ibase8/Spine-t/slides/Spine-t_ankylosing_spondylitis.htm. Access March 30, 2011

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Walton C, Reed C. Ophthalmologic Manifestations of Ankylosing Spondylitis. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1193119-overview. 2010, April.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 MedicineNet.com Ankylosing Spondylitis. http://www.medicinenet.com/ankylosing_spondylitis/article.htm. 2011. March 4, 2011.

- ↑ Brierley C.Major genetic breakthrough for ankylosing spondylitis brings treatment hope. http://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2007-10/wt-mgb101907.php. Oct 2007.

- ↑ Keat A. Ankylosing Spondylitis. Medicine2010; 38:4.185-189.

- ↑ Widberg K, Karimi H, Hafström I. Self- and manual mobilization improves spine mobility in men with ankylosing spondylitis--a randomized study. Clin Rehabil. 2009;23(7):599-608

- ↑ Dagfinrud H, Hagen KB, Kvien TK. Physiotherapy interventions for ankylosing spondylitis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2008, Issue 1. Art. No.: CD002822. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD002822.pub3

- ↑ Magee D. Orthopedic Physical Assessment. Fifth edition. St. Louis, MO: Saunders Elsevier: 2008. 513.

- ↑ ordan CL, Rhon DI. Differential Diagnosis and Management of Ankyosing Spondylitis Masked as Adhesive Capsulitis: A Resident’s Case Problem. J Orthop Sport Phys. 2012;42(10):842-852.

- ↑ Tubergen A, Hidding A. Spa and exercise treatment in ankylosing spondylitis: fact or fancy? Best Practive and Research Clinical Rheumatology. 2002; 16:4. 653-666.

- ↑ Widberg K, Hafstrom I. Self-and manual mobilization improves spine mobility in men with ankylosing spondylitis- a randomized study. Clinical Rehabilitation. 2009; 23: 599-608.

- ↑ Frey L, Haftel H. Shoulder, knee, and hip pain as initial symptoms of juvenile ankylosing spondylitis: a case report. Journal of Orthopedic and Sports Physical Therapy. 1998; 17:2. 167- 172.