Rotator Cuff Tears: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 36: | Line 36: | ||

== Epidemiology/Etiology == | == Epidemiology/Etiology == | ||

Rotator cuff tears are the leading cause of shoulder pain and shoulder-related disability. The pathogenesis of these tears is still partly unknown. | Rotator cuff tears are the leading cause of shoulder pain and shoulder-related disability. The pathogenesis of these tears is still partly unknown. | ||

Rotator cuff tears can be caused by degenerative changes, repetitive micro traumas, severe traumatic injuries, atraumatic injuries and secondary dysfunctions . <br>Traumatic injury to the rotator cuff can be caused by falling on an outstretched hand, by an unexpected force when pushing or pulling, or during shoulder dislocation. <br>Normal age-related muscle deterioration and excessive repetitive motions are examples of atraumatic | Rotator cuff tears can be caused by degenerative changes, repetitive micro traumas, severe traumatic injuries, atraumatic injuries and secondary dysfunctions . <ref name="Horng-chaung et al.">H.Horng-Chaung, Influence of rotator cuff tearing on glenohumeral stability, Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery, 1997, pp 413 – 422, (2B), (E)</ref><br>Traumatic injury to the rotator cuff can be caused by falling on an outstretched hand, by an unexpected force when pushing or pulling, or during shoulder dislocation. <br>Normal age-related muscle deterioration and excessive repetitive motions are examples of atraumatic causes<ref name="Horng-chaung et al." />. | ||

There are many other etiologies implicated in the pathogenesis of rotator cuff tears. Extrinsic factors such as subacromial and internal impingement, tensile overload and repetitive stress can lead to a higher risk of rotator cuff tears. <br>Intrinsic factors such as poor vascularity, alterations in material properties, matrix composition and aging are also involved.(level of evidence: 3a) <br>Smoking and inflammation of the joint capsule (frozen shoulder) can also lead to a higher risk for a rotator cuff tear. Also, thyroid pathologies could play a role in rotator cuff tear pathology. But this relationship needs more research. | There are many other etiologies implicated in the pathogenesis of rotator cuff tears. Extrinsic factors such as subacromial and internal impingement, tensile overload and repetitive stress can lead to a higher risk of rotator cuff tears. <br>Intrinsic factors such as poor vascularity, alterations in material properties, matrix composition and aging are also involved.(level of evidence: 3a) <br>Smoking and inflammation of the joint capsule (frozen shoulder) can also lead to a higher risk for a rotator cuff tear. Also, thyroid pathologies could play a role in rotator cuff tear pathology. But this relationship needs more research. | ||

Revision as of 12:48, 8 May 2016

Original Editor - Lina Taing and Jenna Fried as part of the Temple University Evidence-Based Practice Project

Top Contributors - Descheemaeker Kari, Jenna Fried, Scott Buxton, Anne-Laure Vanherwegen, Lise Buelens, Admin, Lina Taing, Dejonckheere Margo, Kim Jackson, Rachael Lowe, Ellen Vandyck, Selena Horner, Brecht Haex, 127.0.0.1, Kai A. Sigel, Simisola Ajeyalemi, Scott A Burns, Uchechukwu Chukwuemeka, Lauren Lopez, Naomi O'Reilly, Fasuba Ayobami, Johnathan Fahrner and Wanda van Niekerk - Anne-Laure Vanherwegen, Sarah Jacobs, Layla Lemaire and Melissa Evenepoel as part of the Vrije Universiteit Brussel Evidence-based Practice Project Your name will be added here if you are a lead editor on this page.

Search Strategy[edit | edit source]

We searched for information in different scientific medical databases like PubMed, Pedro and Web of Science. Also, we went to a library and lend some books.

We started our search with words like: rotator cuff tear, physiotherapy, rehabilitation, surgery, shoulder therapy, …

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

There isn’t an exact definition of a massive rotator cuff tear. Sometimes the severity is expressed by the number of tendons which are torn, sometimes on the size of the tear.

Lädermann et al. speak of a rotator cuff tear when at least two tendons are completely torn. Next to the number of tendons which are torn, at least one of the two tendons must be retracted beyond the top of the humeral head.[1]

These rotator cuff tears can be further divided into 5 categories (according to Collin et al.)[1]:

- Type A: supraspinatus & superior subscapularis tears

- Type B: supraspinatus and entire subscapularis tears

- Type C: supraspinatus, superior subscapularis & infraspinatus tears

- Type D: supraspinatus & infraspinatus tears

- Type E: supraspinatus, infraspinatus & teres minor tear

Other authors speak of a rotator cuff tear that involves one or more of the four tendons that constitute the rotator cuff. The most common tendon affected is the M. supraspinatus. There are a number of classification systems that are used to describe the size, location and shape of rotator cuff tears. Most commonly tears are described as partial- or full-thickness. A commonly cited classification system for full- thickness rotator cuff tears was developed by Cofield (1982). The classification system is:

1. Small tear: less than 1 cm

2. Medium tear: 1–3 cm

3. Large tear: 3–5 cm

4. Massive tear: greater than 5 cm.

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[2]

[edit | edit source]

The shoulder - or better the shoulder girdle- consists of five joints. Three of them are considered as real. These three real joints are: the glenohumeral joint, the acromioclavicular joint and the sternoclavicular joint. Together with the subacromial joint and the scapulothoracic joint,

the shoulder girdle reaches a large range of motion. Because of this large range of motion, the shoulder girdle is less stable.

The limited passive stability indicates that the primary source of joint stability must be balanced muscle control.

The rotator cuff provides this stability. The rotator cuff exists of four muscles: M. Subscapularis, M. Teres Minor, M. Supraspinatus and M. Infraspinatus.

During shoulder abduction the rotator cuff muscles act together to stabilize the humeral head within the glenoid in a process known as concavity compression.

The rotator cuff muscles contribute to shoulder elevation between 60 and 130 degrees. The Subscapularis muscle makes sure that internal humeral rotation is possible. M. infraspinatus and M. teres minor primarily provide external humeral rotation. All muscles of the rotator cuff, except the M. supraspinatus, ensure that the humeral head stays depressed to balance upward pull of the deltoid early in glenohumeral abduction.

Epidemiology/Etiology[edit | edit source]

Rotator cuff tears are the leading cause of shoulder pain and shoulder-related disability. The pathogenesis of these tears is still partly unknown.

Rotator cuff tears can be caused by degenerative changes, repetitive micro traumas, severe traumatic injuries, atraumatic injuries and secondary dysfunctions . [3]

Traumatic injury to the rotator cuff can be caused by falling on an outstretched hand, by an unexpected force when pushing or pulling, or during shoulder dislocation.

Normal age-related muscle deterioration and excessive repetitive motions are examples of atraumatic causes[3].

There are many other etiologies implicated in the pathogenesis of rotator cuff tears. Extrinsic factors such as subacromial and internal impingement, tensile overload and repetitive stress can lead to a higher risk of rotator cuff tears.

Intrinsic factors such as poor vascularity, alterations in material properties, matrix composition and aging are also involved.(level of evidence: 3a)

Smoking and inflammation of the joint capsule (frozen shoulder) can also lead to a higher risk for a rotator cuff tear. Also, thyroid pathologies could play a role in rotator cuff tear pathology. But this relationship needs more research.

Comorbidities of rotator cuff tears are hormone-related gynecologic diseases, autoimmune pathologies, rheumatoid arthritis and type 1 diabetes mellitus.

Characteristics / Clinical Presentation

[edit | edit source]

The location of the tear has an important influence on the possible dysfunctions.

Individuals with a rotator cuff tear may suffer from1:

- severe pain at time of injury

- pain at night

- pain with overhead activities

- positive painful arc sign

- weakness of involved muscle

- shoulder stiffness.

Individuals with a tear of the supraspinatus may complain of tenderness over the greater tuberosity, pain located in the anterior shoulder and symptoms radiating down the arm.

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Rotator cuff tears must be differentiated from rotator cuff tendinopathy and from bursitis (subacromial bursitis). Arthrography or ultrasonography can make this distinction.

Additional differential diagnosis to look out for are:

- Acromioclavicular injury

- Glenoid labrum tear : Slap lesion, Bankart lesion

- Cervical pathology: Cervical nerve root injury, Cervical Radiculopathy, Cervical Spondylosis

- Subacromial Impingement

-Osteoarthritis, Rheumatoid Arthritis

- Shoulder Instability

- Subscapular nerve entrapment

- Scapulothoracic bursitis

- Adhesive Capsulitis

- Biceps Tendonitis

- Calcific Tendonitis Shoulder

- Parsonage Turner Syndrome, Thoracic Outlet Syndrome

- Glenohumeral ligament tears or sprains

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

Many factors are considered in diagnosing rotator cuff tears. Subjective history including mechanism of injury, aggs, eases and current limitations to function as well as physical examination findings aditionally at times diagnostic imaging are all used to make the diagnosis[4][5][6].

A shoulder examination starts by inspecting the scapula in a resting position from behind. Dynamic scapular dyskinesis is detected by asking the patient to raise and/or abduct both arms repeatedly in a rhythmic motion, until fatigue of the scapular stabilisers results in failure to keep the scapula well positioned in relation to the thoracic wall. Active scapular retraction and elevation are checked. The next step is to look for muscle atrophy and remember active and passive range of motion should be examined and compared with the non‐injured shoulder.

The next step is to perform tests for impingement such as: Neer test, Empty Can est, Hawkins test, external rotation resistance test and instability: sulcus sign, apprehension test, relocation test, hyper abduction test, posterior apprehension test. It is wise to perform several tests as none of them are sufficiently sensitive and specific on their own, these are called clusters[7].

There are several special tests for the shoulder that are purported to detect lesions of the rotator cuff; however, many commonly used tests have poor psychometric properties. To enhance the ability to detect full-thickness rotator cuff tears, two test-item clusters have been developed. These test-item clusters improve the post-test probability for the clinical diagnosis of full-thickness rotator cuff tears[5][6].

Cluster by Murell and Walton 2001[4]

Signs: supraspinatus weakness, weakness in external rotation, signs of impingement

3 signs at any age = 98% probability

2 signs and age < 60 = 98% probability

2 signs and age < 60 = 64% probability

1 sign and age > 70 = 76% probability

Cluster by Park et al 2005[6]

Signs: Drop arm test, painful arc, infraspinatus muscle test

3 + signs = 91% probability

2 + signs = 69% probability

1 + sign = 33% probability

| Test | Sensitivity[6] | Specificity[6] |

| Neer Impingement | .68-.89 | .31-.69 |

| Drop arm test | .27 | .86 |

| Painful arc sign | .33-.74 | .79-.81 |

| Supraspinatus muscle strength test | N/A | N/A |

| Infraspinatus muscle strength test | .42 | .90 |

An IMPT (isokinetic muscle performance test) of the shoulder provides objective, reliable and valuable perioperative data, which can be used to estimate the functional status of the rotator cuff muscles and can provide quantitative data for anatomic assessment of the rotator cuff. These findings can also offer objective guidelines for interpreting muscle strength in patients with a rotator cuff disorder[8].

You need a Biodex System 3 PRO® (Biodex Corp, Shirley, NY) to perform the test. The IMPT reportedly has high accuracy and test-retest reliability in evaluating the shoulder musculature comple and provides information regarding patients’ actual muscle function and strength[8].

Outcome Measures

[edit | edit source]

The following bullet point list contains commonly used shoulder outcome measures and is by no means exhaustive. Your own clinical discression will need to be sued to determine the most useful measure in your clinical setting.

- Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand (DASH)[9]

The DASH is a questionnaire, scored in 2 subscales. First there is the disability or symptom section, which consists of 30 items, each scored from 1 to 5. And second there is the optional high performance sports/music or work section, which consists of 4 items, each also scored from 1 to 5.

- Quick DASH

The QuickDASH is the shorter version of the DASH outcome measure. The QuickDASH is also scored in 2 components. The first one is the disability or symptom section, which has only 11 items, scored from 1 to 5. And the second component is the optional high performance sports/music or work module, which has 4 items, also scored from 1 to 5.

- Penn Shoulder Score (PSS)[10]

The PSS is a 100-point questionnaire consisting of 3 subscales, pain, function and satisfaction. It is a valid and reliable measure to report the outcome of patients with all kinds of shoulder disorders.

- Global Rating of Change Scale (GRCS)[11]

The GRCS is a measure that rates the changes in symptoms, in this case in the shoulder. It compares the symptoms with those from 12 months earlier. There are 15 possible scores, ranging from -7 (the worst) to +7 (the best).

- Constant-Murley Score (CMS)[12]

This measure rates objective and subjective elements of pain and function in the shoulder. The final score ranges from 0 to 100, with 0 as the worst result possible and 100 as the best result possible.

The RC-QOL is a disease-specific outcome measure that evaluates the impact of rotator cuff diseases on the general quality of life. It is a questionnaire with 34 items, divided into 5 domains. These 5 domains are: symptoms and physical complaints, work-related concerns, sports and recreation, lifestyle issues and finally social and emotional issues.

The SPADI is created to measure pain and disabilities associated with shoulder pathology in patients with shoulder pain of musculoskeletal, neurogenic or undetermined origin. There are 2 domains, pain and disability, with 13 items in total. Every item is scored on a visual analog scale, ranging from 0 (no pain/no difficulty) to 10 (worst pain imaginable/so difficult that help is required).

- American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons score (ASES)[9]

The ASES is used to measure shoulder pain and functional limitations in patients with musculoskeletal complaints. The pain is measured with a visual analog scale. The domain ‘Function’ is divided into 10 questions, using a 4-point ordinal scale. The total score ranges from 0 to 100 points, where 0 is the worst and 100 is the best.

- UCLA Shoulder Score[15]

The self-report part of the measure consists of 2 single-item subscales (pain and function). These are Likert-type scales and are scored from 1 to 10: a higher score indicates a lower pain and greater function.

- Simple Shoulder Test (SST)[15]

The SST is a function scale with 12 items, checking the patients’ ability to tolerate or perform 12 activities of daily living. The scores range from 0 to 100 and are reported as the percentage of items that were answered.

Examination[edit | edit source]

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

Conservative management is warranted in most rotator cuff injuries. In addition to physical therapy, non-surgical treatment may include non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and steroid injections, time, local rest, application of cold or heat and massage. The judicious use of no more than three to four injections of steroids into the subacromial space or around the biceps tendon can be helpful in the early phase[16].

Initial physical therapy interventions may include:

- Mobility exercises including PROM, AAROM, AROM

- Motor control training

- Scapular stabilization

- Stretching[17]: Posterior capsular contracture is addressed by progressive stretching in adduction and internal rotation. Horizontal adduction or cross-body adduction exercises are recommended to release the posterior capsule[16].

- Isometric and low-grade strengthening exercises: as pain decreases and the range of movement increases, strengthening exercises for the rotator cuff and periscapular musculature are prescribed to restore the normal mechanics of the shoulder girdle. Progressive resistive exercises are employed within the limits of the pain utilising rubber tubing or free weights[16].

- Manual therapy directed at the GH, AC and SC joint. Manual therapy includes massage therapy, especially the use of deep frictions of the muscles, stretching of the radial nerve, mobilization of the scapula and the glenohumeral joint. More so, proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation techniques have proven themselves useful. These manual therapies have some striking advantages, i.e. they are able to shorten the total treatment period and they relieve the pain significantly, which is along with the repair of the shoulder range of motion, the main goal of manual therapy[18].

- Manual therapy of cervicothoracic spine and upper ribs

- Activity modification

Late stages of rehabilitation of rotator cuff injury include progressive resistive strengthening, proprioception and sport-specific exercises.

In general there seems to be a higher success rate when using non-surgical methods of intervention. Whether or not a surgery will take place, depends on the wish and the individual characteristics of the patient.

As an example: for a younger patient it is more important to regain the strength and the functionality of his muscles, where for an older patient, surgery might hold too much risk and the main goal is to relieve the pain instead of reaching the full potential of the muscles.

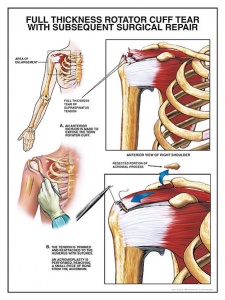

Indications for a surgical repair are pain and/or weakness, even after 3 to 6 months of conservative therapy. Examples of surgical treatment include debridement, debridement with acromioplasty, or rotator cuff repair (arthroscopic)[19].

Key Research[edit | edit source]

No randomized control trials have found an optimal conservative management of rotator cuff tears. Several studies have shown reduction in pain and disability by treating regions remote to the shoulder. This concept has been coined regional interdependce. Thrust and non-thrust manipulation of the cervicothoracic spine and/or ribs may lead to significant improvement in pain and disability in patients with a primary complaint of shoulder pain7,8.

Resources[edit | edit source]

Rotator cuff tears and rehabilitation, Richard Hawkins, M.D.:

Rotator cuff tear and rehabilitation, Dr. Sean Simmonds:

Rotator cuff tear: Diagnosis & treatment

Clinical Bottom Line[edit | edit source]

Conservative Management of a Large Rotator Cuff Tear to Increase Functional Abilities: A Case Report

Recent Related Research (from Pubmed)[edit | edit source]

Failed to load RSS feed from http://eutils.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/erss.cgi?rss_guid=10IsjDYWWF_fcPKUaRcMUStihMNVL7ESME_VRb7qYbvo7C39wQ|charset=UTF-8|short|max=10: Error parsing XML for RSS

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Lädermann, Alexandre, Patrick J. Denard, and Philippe Collin. "Massive rotator cuff tears: definition and treatment." International orthopaedics (2015): 1-12. (2C)

- ↑ N. Yamamoto, A review of biomechanics of the shoulder and biomechanical concepts of rotator cuff repair. Asia-Pacific Journal of Sports Medicine, Arthroscopy, Rehabilitation and Technology. Volume 2, Issue 1, January 2015, Pages 27–30. (2A)

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 H.Horng-Chaung, Influence of rotator cuff tearing on glenohumeral stability, Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery, 1997, pp 413 – 422, (2B), (E)

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Murrell GA, Walton JR. Diagnosis of rotator cuff tears. The Lancet. 2001;357(9258):769-770.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Smith M, Smith W. Rotator cuff tears: an overview. Orthopaedic Nursing [serial online]. September 2010;29(5):319-324. Available from: CINAHL, Ipswich, MA. Accessed March 17, 2011.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 Park HB, Yokota A, Gill HS, El Rassi G, McFarland EG. Diagnostic accuracy of clinical tests for the different degrees of subacromial impingement syndrome J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(7):1446-1455.

- ↑ Van der Hoeven H. et al. Shoulder injuries in tennis players. Br J Sports Med. 2006 May; 40(5): 435–440. (1A), (A)

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Han Oh et al. Isokinetic Muscle Performance Test Can Predict the Status of Rotator Cuff Muscle. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010 June; 468(6): 1506–1513. (2B), (C)

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Jean-Sébastien Roy. Measuring Shoulder Function: A systematic Review of Four Questionnaires. Arthritis &amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp; Rheumatism, vol 61, No 5, 2009, pp 623- 632. (1A), (A)

- ↑ Brian G Leggin. The Penn Shoulder Score: Reliability and validity. Journal of Orthopaedic &amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp; Sports physical therapy. 2006; 36: 138-151. (2B), (B)

- ↑ Steven J Kamper. Global Rating of change scales: A review of strengths and weaknesses and considerations for design. The Journal of Manual &amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp; Manipulative Therapy. 2009; 17(3): 163-170 (1A), (A)

- ↑ Mohammed N Yasin. The reliability of the Constant-Murley shoulder scoring system. Shoulder and Elbow 2010; 2, pp 259-262. (2B), (C)

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Hollinshead RM. Two 6-year follow-up studies of large and massive rotator cuff tears: comparison of outcome measures. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2000 sep-oct; 9(5): 373-81. (3B), (C)

- ↑ Rocco Papalia. RC-QOL score for rotator cuff pathology: adaptation to Italian. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrose – Shoulder 2010, 18: 1417-1424. (2B), (C)

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Roddey T. S. Comparison of the University of California-Los Angeles Shoulder Scale and the Simple Shoulder Test with the Soulder Pain and Disability Index: Single –Administration Reliability and Validity. Journal of the American Physical Therapy Association. 2000; 80:759-768. (2B), (B)

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Fukuda H, The Management of PArtial Thickness Tears of the Rotator cuff. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, 2003, pp 3 -11. (1A), (A)

- ↑ Desmond J. M.D, Results of Nonoperative Management of Full-Thickness Tears of the Rotator Cuff, Clinical Orthopaedics &amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp;amp; Related Research, September 1993(3B), (C)

- ↑ Senbura, G. Baltaci, Ö.A Atay. The effectiveness of manual therapy in supraspinatus tendinopathy. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc. 2011. (2B), (B)

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedGomoll