Red Flags in Spinal Conditions: Difference between revisions

Anna Butler (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

Anna Butler (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| Line 67: | Line 67: | ||

In the UK age above 55 years is considered a red flag (CSAG 1994), this is because above this age, particularly above 65, the chances of being diagnosed with many serious pathologies, such as cancers, increase (Greenhalgh and Selfe). | In the UK age above 55 years is considered a red flag (CSAG 1994), this is because above this age, particularly above 65, the chances of being diagnosed with many serious pathologies, such as cancers, increase (Greenhalgh and Selfe). | ||

== | == Medical history == | ||

=== Cancer === | === Cancer === | ||

| Line 101: | Line 101: | ||

=== Osteoporosis<br> === | === Osteoporosis<br> === | ||

Osteoporosis can lead to an increased risk of vertebral fracture. The main risk factors for osteoporosis are: | Osteoporosis can lead to an increased risk of vertebral fracture. The main risk factors for osteoporosis are: | ||

*Female, post menopause | *Female, post menopause | ||

*Of White or Asian race | *Of White or Asian race | ||

*Family history of osteoporosis on materal side | *Family history of osteoporosis on materal side | ||

*Absence of menstruation | *Absence of menstruation | ||

*Smoker | *Smoker | ||

* Heavy drinker (female >14 units a week, male >21 units week) | * Heavy drinker (female >14 units a week, male >21 units week) | ||

*Poor diet and exercise | *Poor diet and exercise | ||

*Drug history of corticosteriods, immunosuppressants or chemotherapy | *Drug history of corticosteriods, immunosuppressants or chemotherapy | ||

*Past medical history of Crohn's diease, kidney or liver dieases or a gastrectomy | *Past medical history of Crohn's diease, kidney or liver dieases or a gastrectomy | ||

Revision as of 14:10, 12 January 2014

Original Editor - Anna Butler, Fiona Stohrer and Kat Moon .... as part of the Nottingham University Spinal Rehabilitation Project

Top Contributors - Katherine Moon, Fiona Stohrer, Anna Butler, Admin, Kim Jackson, Naomi O'Reilly, Rachael Lowe, WikiSysop, Claire Knott, Jess Bell, Gunilla Buitendag, Tarina van der Stockt, Simisola Ajeyalemi, Shaimaa Eldib and 127.0.0.1

What are red flags?

[edit | edit source]

Part of the UK guidelines for an assessment of lower back pain is to rule out serious pathology and identify red flags (Koes et al. 2010). Red flags are features from a patients subjective and objective assessment which is thought to put them at a higher risk of serious pathology and warrant referral for further diagnostic testing (Henschke et al. 2013). Red flags often highlight non-mechanical conditions or pathologies of visceral origin (E. Mulligan). Red flags can be contraindications to many Physiotherapy treatments.

Although red flags have a valid role to play in assessment and diagnosis they should also be used with caution. Some guidelines contain no information on diagnostic accuracy for individual red flags, so it is the responsibility of individual practitioners to make themselves aware of these. Other guidelines even recommend immediate referral to imaging if any red flag is present, which could lead to many unnecessary referrals if clinicians did not clinically reason their referral (Downie et al. 2013).

History of red flags[edit | edit source]

The role of Physiotherapists in identifying red flags has changed as Physiotherapists increasingly become a patients first point of contact with a healthcare professional. In McKenzies 1990 book he states that “the patient once screened by the medical practitioner, should have any unsuitable pathologies excluded.” Within today’s healthcare system patients may not have even been seen by a doctor before they present to a Physiotherapist as there is more scope for self referral and private clinics. The term ‘red flag’ was first used by the Clinical Standards Advisory Group in 1994. However, similar high risk markers date back to Mennell in 1952 and Cyriax in 1982 (Greenhalgh and Selfe 2006).

Red Herrings[edit | edit source]

Red Herrings are “any misleading biomedical or psychosocial factors that will deflect the course of accurate clinical reasoning” (Greenhalgh). When assessing lower back pain red herrings can mislead a clinician into misdiagnosis resulting in a delay in appropriate treatment for the pathology causing the lower back pain.

Spinal Masqueraders

[edit | edit source]

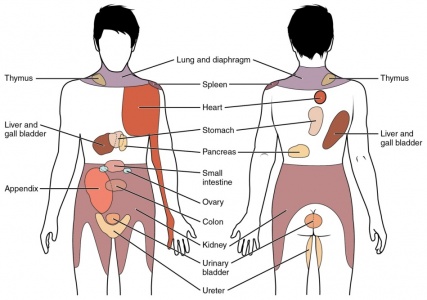

Spinal masqueraders are conditions which present as lower back pain but are actually caused by non-mechanical referred pain from a structure not part of the spine.

Spinal masqueraders are examples of where red herrings can sometimes lead to misdiagnosis. Patients will present with lower back pain but the source is not a mechanical structure (Walcott et al 2011). Although the percentage of patients seen by Physiotherapists with these conditions is small it is important to be able to recognise the red flags that could point towards these conditions.

Some of the sources of visceral pain include:

• Inflammation - eg appendicitis

• Distention - eg bowel obstruction

• Ischemia - eg a tumour blocking blood supply

The blood supply to internal organs is in close proximity to the sympathetic nerve system so changes to the blood supply from ischemia, distention of inflammation can directly affect the nerve innervation (Eveliegh 2013).

This diagram depicts the most commong referral patterns for visceral pathologies.

(Eveliegh 2013)

Epidemiology of red flags[edit | edit source]

It is hard to get an exact picture of the epidemiology of red flags as it depends heavily on the level of documentation by clinicians. One study by Leerar et al, 2007 suggested that “the documentation of red flags was comprehensive in some areas (age over 50, bladder dysfunction, history of cancer, immune suppression, night pain, history of trauma, saddle anaesthesia and lower extremity neurological deficit) but lacking in others (weight loss, recent infection, and fever/chills)”.

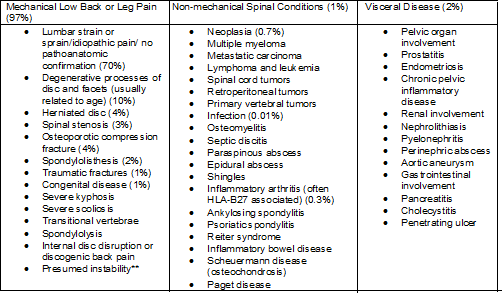

This model was suggested by the 1994 Clinical Standards Advisory Group for the proportion of serious spinal pathologies.

This table shows further breakdown of the conditions lower back pain patients present with.

- Figures in brackets indicate estimated percentages of patients with these conditions among all adult patients with signs and symptoms of low back pain. Percentages may vary substantially according to demographic. Data obtained from Deyo et al

(Jarvik et al. 2002)

Subjective History[edit | edit source]

Age[edit | edit source]

In the UK age above 55 years is considered a red flag (CSAG 1994), this is because above this age, particularly above 65, the chances of being diagnosed with many serious pathologies, such as cancers, increase (Greenhalgh and Selfe).

Medical history[edit | edit source]

Cancer[edit | edit source]

A patient history of cancer and also family history of cancer should be established, particularly in a first degree relative, such as a parent or sibling (Greenhalgh and Selfe). The most common forms of metastatic cancer are: breast, lung and prostate (Jarvik 2002).

The most common warning signs of cancer are:

- Change in bowel or bladder habits

- Sores that do not heal

- Unusual bleeding or discharge

- Thickening or lump in breast elsewhere

- Indigestion or difficulty swallowing

- Obvious change in wart or mole

- Nagging cough or hoarseness

(Greenhalgh and Selfe)

Tuberculosis[edit | edit source]

Tuberculosis can sometimes cause lower back pain. The most common symptoms of tuberculosis are:

- Pain in the thoracolumbar junction and decreased range of motion

- Weight loss

- Fever

- Neurological compromise

- Malaise

- Skeletal involvement

- Abscesses in the groin, greater trochanter or buttock

(Greenhalgh and Selfe)

Osteoporosis

[edit | edit source]

Osteoporosis can lead to an increased risk of vertebral fracture. The main risk factors for osteoporosis are:

- Female, post menopause

- Of White or Asian race

- Family history of osteoporosis on materal side

- Absence of menstruation

- Smoker

- Heavy drinker (female >14 units a week, male >21 units week)

- Poor diet and exercise

- Drug history of corticosteriods, immunosuppressants or chemotherapy

- Past medical history of Crohn's diease, kidney or liver dieases or a gastrectomy

(Greenhalgh and Selfe)

Lifestyle[edit | edit source]

Smoking[edit | edit source]

Smoking can cause lower back pain as smoking has adverse affects on circulation, therefore decreasing the nutritional supply getting to the intervertebral disk and vertebrae. Over time this leads to degeneration of these structures and therefore instability which can cause lower back pain. It has also been suggested that regular coughing, which if often associated with smoking, can also lead to increased mechanical stress on the spine (Greenhalgh and Selfe).

Recent weight loss[edit | edit source]

Pain[edit | edit source]

Constant pain[edit | edit source]

Thorcacic pain[edit | edit source]

Severe night pain[edit | edit source]

Current Symptoms[edit | edit source]

Systemically unwell

[edit | edit source]

Bilateral pins and needles

[edit | edit source]

Abdominal pain and changed bowel habits with no change in medication[edit | edit source]

Trauma[edit | edit source]

Previous failed treatment[edit | edit source]

Objective History[edit | edit source]

Physical Appearance[edit | edit source]

Determine if the patient is unwell however this is a very subjective concept. The following signs may indicate that the patient has a systemic serious pathology (Greenhalgh and Selfe, 2006).

General Signs to indicate that a patient is unwell:

• Pallor/flushing

• Sweating

• Altered complexion: sallow/jaundiced

• Tremor/shaking

• Tired

• Dishevelled/unkempt

• Halitosis

• Poorly fitting clothes

Observation[edit | edit source]

Posture[edit | edit source]

It is important to note any posture alterations as this can give the therapist some indication of levels of pain (Greenhalgh and Selfe, 2006).

Deformity of the spine[edit | edit source]

Observe any deformities of the spine. A deformity with associated muscle spasm and severe limitation of movement are suggested to be key indicators of spinal pathology (Greenhalgh and Selfe, 2006). A rapid onset of a scoliosis is indicative of an osteoma or osteoblastoma. This may not appear when standing straight and the patient may need to flex forwards first (Greenhalgh and Selfe, 2006). It may also affect the patients’ ability to move into physiological movements (Greenhalgh and Selfe, 2006).

Some tumors can be large enough to be seen or felt. Swelling and tenderness may be the first sign of a tumour (Greenhalgh and Selfe, 2006).It is also common for tumours to restrict movement eg. restricting spinal flexion.

Muscle Spasm[edit | edit source]

This is suggested to be synonymous with low back pain and is therefore difficult to determine if it is associated with a red flag pathology (Greenhalgh and Selfe, 2006). If a serious spinal pathology is present, the muscle spasm may be so severe to cause a scoliosis in the spine. The correlation between muscle spasm, pain and other objective clinical measurements however, are poorly supported by strong evidence (Greenhalgh and Selfe, 2006).

Neurological Assessment[edit | edit source]

Patients who report neurological signs in the objective assessment require a neurological assessment (Petty and Moore, 2001). A neurological deficit is rarely the first presenting symptom in a patient with serious spinal pathology however 70% of patient will have a neurological deficit at the time of diagnosis (Greenhalgh and Selfe, 2006).

The dermatomes, myotomes and reflexes should be examined. The upper motor neurone should also be examined via extensor plantar reflex (Babinski), clonus and hoffmans. If it is gained easily, it may indicate MS (Greenhalgh and Selfe, 2006). There should be a high index of suspicion if the patient has two or more affected nerve roots (Greenhalgh and Selfe, 2006).

Diagnostic Tests[edit | edit source]

What is differential diagnosis?

A systematic process in which tools such as clinical tests are used to identify the proper diagnosis from a competing set of possible diagnoses. (Whiting et al, 2008)

For a clinical test to be the best test?

• Reliable

• Low Cost

• Validated findings

• High diagnostic Accuracy = SPECIFICITY AND SENSITIVITY

SPECIFICITY

Is the percentage of people who test negative for a specific disease among a group of people who do not have the disease (Sackett et al 2000)

SENSITIVITY

Percentage of people who test positive for a specific disease among a group of people who have the disease (Sackett et al, 2000).

Likelihood ratio = The Likelihood Ratio (LR) is the likelihood that a given test result would be expected in a patient with the target disorder compared to the likelihood that that same result would be expected in a patient without the target disorder. (http://www.cebm.net/?o=1158)

http://www.physio-pedia.com/Test_Diagnostics

High sensitivity and LOW LR = RULE OUT people who don’t have the disease

High specificity and HIGH LR = RULE IN people who have the disease

Percussion test

Tests : Compression fractures

The examiner stands behind the patient. The patient stands facing a mirror so that the examiner can gauge their reaction. The entire length of the spine is examined using firm, closed-fist percussion.

Positive = when the patient complains of a sharp, sudden pain.

Table 1. A table to show sensitivity, specificity and likelihood ratios of the Percussion diagnostic test for compression fracture. (Langdon et al 2009)

Clinical Reasoning[edit | edit source]

Clinical Reasoning is integral to physiotherapy practice. It has been suggested that as a concept, clinical reasoning is quite a simple one however in practice, it is difficult and fraught with errors. The aim of clinical reasoning is to prevent misdirection (Jones, 1995).

Clinical Reasoning can strongly influence how the case is interpreted by the therapist. This has implications as to how the clinician views the red flags presented therein (Greenhalgh and Selfe, 2004).

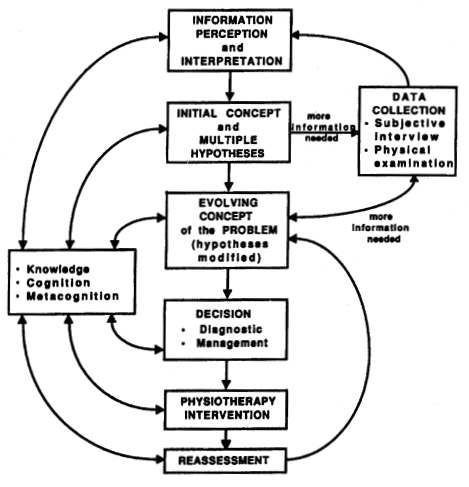

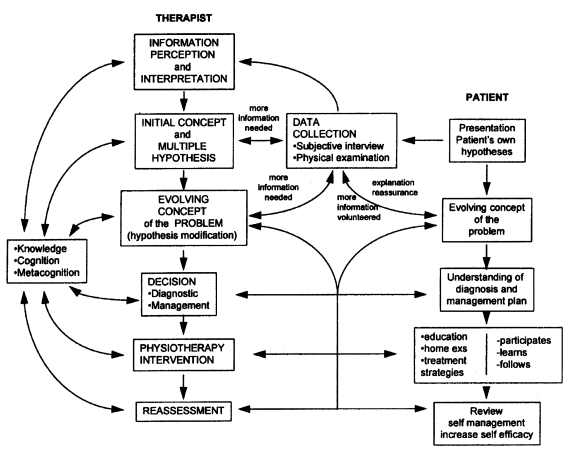

The most common form of clinical reasoning within the physiotherapy profession is hypothetico-deductive reasoning (Doody and McAteer, 2002). Hypothetico-deductive reasoning, the clinician gains initial clues in regards to the patients problem (from the subjective assessment) which forms initial hypothesis in the therapists mind. Further data is collected in the objective assessment and the hypothesis is tested (special tests) and interpreted. This may confirm on negate the hypothesis. Continual hypothesis generation occurs during management and reassessment (Edwards, Jones, Carr et al. 2004).

Reflection after the assessment and also after the subsequent sessions will provide the clinical with patterns and their reasoning practice will increase. Without reflection, clinician’s will have no progress in their clinical reasoning (Jones, 1995, Greenhalgh, 2008).

Process of Clinical Reasoning[edit | edit source]

Clinical reasoning should begin as soon as you meet the patient as their behaviour can inform your thinking (Greenhalgh and Selfe, 2006). There should be ongoing data collection which should not stop at the end of the assessment. A hyptothetico-deductive model of clinical reasoning can be seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1: A Hypothetico-deductive model of Clinical Reasoning (Jones, 1995).

The therapist may be able to ascertain quickly that something is wrong with the patient due to the subjective and objective assessment and their clinical reasoning. Continuous re-assessment is important to ensure the collection of data gathered is collated together. This will contribute to the therapists evolving concept of the patients’ problem (Greenhalgh and Selfe, 2006, Jones, 1995).

Pattern Recognition[edit | edit source]

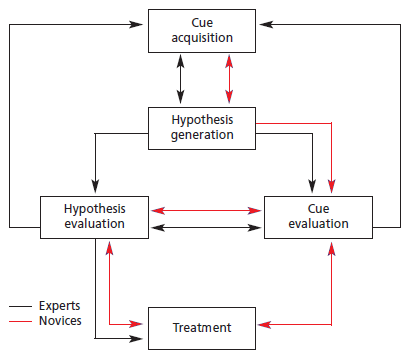

Pattern recognition is an important part of clinical reasoning however this will be limited in students and newly qualified physiotherapists (Jones, 1995, Doody and McAteer, 2002).

Knowledge is also an important consideration as being able to have knowledge in a particular area and to be able to process that knowledge appropriately will be important as to what is given to each hypothesis (Jones, 1995). There is suggested to be differences in novice and expert therapists (Doody and McAteer, 2002) (See Figure 2). Although largely similar, novice physiotherapists have to go through a longer process of clinical reasoning compared to expert therapists. Expert therapists are determined as having at least 3 years of experience whereas novice therapists have under three years’ experience or are students (Doody and McAteer, 2002).

Figure 2: Difference in clinical reasoning between expert and novice therapists (Doody and McAteer, 2002).

Patient involvement in the clinical reasoning process[edit | edit source]

The patient should be an integral part of the clinical reasoning process as this can help the clinician to form hypothesis and lead towards the review of the outcome post physiotherapy intervention (Jones, 1995) (See Figure 3).

Figure 3: Patient involvement in the clinical reasoning process (Jones, 1995)

Errors in Clinical Reasoning[edit | edit source]

Patients’ inappropriate misattribution of insidious symptoms to a traumatic event is common and can be misleading (Greenhalgh and Selfe, 2004). Clinical reasoning is only as good as the information on which it is based. Also, clinical reasoning will only be appropriate if the therapist undertakes correct questioning (Greenhalgh, 2008).

The three types of errors that can occur in clinical reasoning include:

- Faulty perception or elicitation of cues

- Incomplete factual knowledge

- Misapplication of known facts to a specific problem

Red Herrings[edit | edit source]

Do not be reassured by previous investigations being reported on as normal, how do you know they were investigating the correct aspect or area (Greenhalgh, 2008). In the early stages, serious spinal pathology is difficult to detect and weight loss will not always be evident in these early stages (Greenhalgh and Selfe, 2003).

Management of red flags[edit | edit source]

The physiotherapist should be aware of the red flags of the spine and refer patients onwards if required.

Students Responsibility[edit | edit source]

Whilst on a clinical placement, it is the students’ responsibility to inform the clinical educator if they find a red flag and document appropriately in the clinical notes. This will allow the educator to perform the assessment again if required.

Onward referral to Accident and Emergency[edit | edit source]

In some cases the red flags may be obvious. If serious enough, the therapist may refer onto Accident and Emergency. This may be the case in cauda equina syndrome for further surgical opinion (Chau, Xu, Pelze et al. 2013).

The patient however may not present with clear red flags and physiotherapy intervention may continue.

Referral Back to the GP[edit | edit source]

Failure to improve after one month is a red flag and the patient can be referred back to the GP for continued management and further diagnostic tests as required(Greenhalgh and Selfe, 2006).

Further Specialist Medical Opinion[edit | edit source]

As well as a referral back to the GP, further specialist medical opinions can be gained (Carvalho, 2007).

Documentation[edit | edit source]

After onward referral red flags must be acknowledged in the notes as this will indicate contraindication to physiotherapy (Carvalho, 2007). Physiotherapist documentation of red flags has been suggested to be documented 98% of the time for the main red flags:

• Age over 50

• Bladder dysfunction

• History of cancer

• Immunosuppression

• Night pain

• History of trauma

• Saddle anaesthesia

• Lower extremity neurological deficit

Red flags that were not documented routinely included:

• Weight loss

• Recent infection

• Fever/chills

(Leerar, Boissonnault, Domholdt et al. 2007).

Recent Related Research (from Pubmed)[edit | edit source]

Extension:RSS -- Error: Not a valid URL: Feed goes here!!|charset=UTF-8|short|max=10

References[edit | edit source]

References will automatically be added here, see adding references tutorial.

Jones et al.