Plantar Grasp Reflex: Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

'''Original Editor '''- [[User:Ahmed Essam |Ahmed Essam]] '''Top Contributors''' - {{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}} | <div class="editorbox">'''Original Editor '''- [[User:Ahmed Essam |Ahmed Essam]] '''Top Contributors''' - {{Special:Contributors/{{FULLPAGENAME}}}}</div> | ||

== Introduction == | == Introduction == | ||

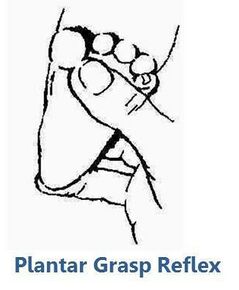

[[File:Plantar Grasp Reflex.jpg|right|frameless|290x290px]]This reflex in human infants can be regarded as a rudiment of responses that were once essential for ape infants in arboreal life. The '''spinal center''' for this reflex is probably located at the '''L5-S2 levels''', which, however, are controlled by higher [[Brain Anatomy|brain]] structures. Nonprimary motor areas may exert regulatory control of the spinal reflex mechanism through [[interneurons]]. In infants, this reflex can be elicited as the result of insufficient control of the spinal mechanism by the immature brain. In adults, lesions in nonprimary motor areas may cause a release of inhibitory control by spinal interneurons, leading to a reappearance of the reflex.<ref name=":0">Futagi Y, Suzuki Y. [https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0887899410001773 Neural mechanism and clinical significance of the plantar grasp reflex in infants.] Pediatric neurology. 2010 Aug 1;43(2):81-6.</ref> <ref>[https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK553125/figure/article-22413.image.f2/ Plantar Reflex]. Contributed from Ashley Arbuckle, Flickr under Creative Commons License (CC By 2.0 <nowiki>https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/</nowiki>)</ref> | [[File:Plantar Grasp Reflex.jpg|right|frameless|290x290px]]This reflex in human infants can be regarded as a rudiment of responses that were once essential for ape infants in arboreal life. The '''spinal center''' for this reflex is probably located at the '''L5-S2 levels''', which, however, are controlled by higher [[Brain Anatomy|brain]] structures. Nonprimary motor areas may exert regulatory control of the spinal reflex mechanism through [[interneurons]]. In infants, this reflex can be elicited as the result of insufficient control of the spinal mechanism by the immature brain. In adults, lesions in nonprimary motor areas may cause a release of inhibitory control by spinal interneurons, leading to a reappearance of the reflex.<ref name=":0">Futagi Y, Suzuki Y. [https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0887899410001773 Neural mechanism and clinical significance of the plantar grasp reflex in infants.] Pediatric neurology. 2010 Aug 1;43(2):81-6.</ref> <ref>[https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK553125/figure/article-22413.image.f2/ Plantar Reflex]. Contributed from Ashley Arbuckle, Flickr under Creative Commons License (CC By 2.0 <nowiki>https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/</nowiki>)</ref> | ||

Revision as of 13:50, 14 April 2022

Introduction[edit | edit source]

This reflex in human infants can be regarded as a rudiment of responses that were once essential for ape infants in arboreal life. The spinal center for this reflex is probably located at the L5-S2 levels, which, however, are controlled by higher brain structures. Nonprimary motor areas may exert regulatory control of the spinal reflex mechanism through interneurons. In infants, this reflex can be elicited as the result of insufficient control of the spinal mechanism by the immature brain. In adults, lesions in nonprimary motor areas may cause a release of inhibitory control by spinal interneurons, leading to a reappearance of the reflex.[1] [2]

Incidence and Prevalence[edit | edit source]

Age incidence-According to research done by Brain and Curran in fifty participants this reflex was elicitable in all children aged nine months or less, and in almost all aged under a year, while it had disappeared in all but one child over the age of two years. This child, aged 3 years, suffered from rickets and showed both the grasp-reflex and extensor plantar responses.[3]

Prevalence-The prevalence in healthy adults aged 65 and older is estimated to be 0.1%. The prevalence in adults 65 and older with mild cognitive impairment is estimated to be 1.7%, and the prevalence in adults 65 and older with dementia is estimated to be 18.4%.[4]

Position[edit | edit source]

Infant lying on a flat surface in the supine position while awake, head and arms at the neutral position. [5][6][7][8][1]

Care should be taken to keep the subject’s head facing the midline, to avoid the influence of the asymmetric tonic neck reflex.[1]

Stimulus[edit | edit source]

The plantar grasp reflex is elicited:-

- By pressing a thumb against the sole of the foot just behind the toes.[1][5][6][7][8] OR

- By stroking gently the plantar surface medially with a blunt object such as the handle of a reflex hammer.[9]

Response[edit | edit source]

Normal Response[edit | edit source]

In Infants-The lateral surfaces of the foot bend as if to make a cup out of the plantar surface.[9] It consists of the flexion and adduction of all toes as if the toes were firmly grasping the stimulating object[3]; there is hollowing of the sole with some wrinkling of the skin. If the toes also flex, this is called the tonic foot response.[9] It is tonic in character, because the posture is often maintained for 15 or 30 seconds, or longer during early infancy[3]

In adults- no response - as it diminishes in later life.

Abnormal Response[edit | edit source]

In Infants- No response means there is underlying pathology.

In adults- If flexion or adduction of toes occurs it means there is underlying pathology.

Duration[edit | edit source]

The plantar grasp reflex can be elicited in all normal infants from 25 weeks of postconceptional age until the end of 6 months of corrected age according to the expected birth date.[1]

The therapist presses her finger at the sole of the foot just behind the toes.

Clinical Significance[edit | edit source]

The plantar grasp reflex in infants is of high clinical significance. A negative or diminished reflex during early infancy is often a sensitive indicator of spasticity. Infants with athetoid type cerebral palsy exhibit extremely strong retention of the reflex, and infants with mental retardation also exhibit a tendency toward prolonged retention of the reflex.[1]

A reduced or negative plantar grasp reflex during early infancy can be a sensitive indicator of later development of spasticity.[1]

Reappearance in adults- More recent studies have implicated lesions of the medial frontal cortex anterior to the primary motor cortex, i.e., the supplementary motor area and cingulate motor cortex, as the etiology of the palmar (or plantar) grasp reflex.[8][11][12][13]

The plantar grasp reflex is usually present at or soon after birth; it is remarkably constant and active during early infancy, and usually disappears between 6 and 12 months of age. The disappearance of the plantar grasp reflex appears to be related to the age of standing.[14]

Reference[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 Futagi Y, Suzuki Y. Neural mechanism and clinical significance of the plantar grasp reflex in infants. Pediatric neurology. 2010 Aug 1;43(2):81-6.

- ↑ Plantar Reflex. Contributed from Ashley Arbuckle, Flickr under Creative Commons License (CC By 2.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/)

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Brain Wr, Curran Rd. The grasp-reflex of the foot. Brain. 1932 Sep 1;55(3):347-56.

- ↑ Hogan DB, Ebly EM. Primitive reflexes and dementia: results from the Canadian Study of Health and Aging. Age and ageing. 1995 Sep 1;24(5):375-81.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Futagi Y, Suzuki Y, Goto M. Clinical significance of plantar grasp response in infants. Pediatric Neurology. 1999 Feb 1;20(2):111-5.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Prechtl H, Beinthema D. Reflexes and responses: The neurological examination of the full-term newborn infant. Clin Dev Med. 1977;63:40-2.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Touwen B. Reactions and responses: neurological development in infancy. Clinics in Developmental Medicine. 1976;58:83-98.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Schott JM, Rossor MN. The grasp and other primitive reflexes. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 2003 May 1;74(5):558-60.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Walker HK. The suck, snout, palmomental, and grasp reflexes. Clinical Methods: The History, Physical, and Laboratory Examinations. 3rd edition. 1990.

- ↑ Nicole Edmonds. Plantar Grasp Reflex. Available from:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vy18c5oGLSk

- ↑ Hashimoto R, Tanaka Y. Contribution of the supplementary motor area and anterior cingulate gyrus to pathological grasping phenomena. Eur Neurol 1998;40:151-8

- ↑ Goldberger ME. Restitution of function in the CNS: The pathologic grasp in Macaca mulatta. Exp Brain Res 1972;15:79-96

- ↑ Smith AM, Bourbonnais D, Blanchette G. Interaction between forced grasping and a learned precision grip after ablation of the supplementary motor area. Brain Res 1981;222:395-400

- ↑ Dietrich HF. A longitudinal study of the Babinski and plantar grasp reflexes in infancy. AMA journal of diseases of children. 1957 Sep 1;94(3):265-71.