Pelvic Floor Dysfunction

Original Editors - Sarah Barnes, Chris Van Wyk, Amy McCarthy, Gina McLoughlin, John Lavin, Claire Ramsden and Carolinne Cieslak.

Top Contributors - Sarah Barnes, Carolinne Cieslak, Gina McLoughlin, Kim Jackson, Claire Ramsden, Chris Van Wyk, Amy McCarthy, John Lavin, Vidya Acharya, Nicole Hills and Rachael Lowe

Learning Outcomes[edit | edit source]

Add your content to this page here!

Overview[edit | edit source]

What is the Pelvic Floor?

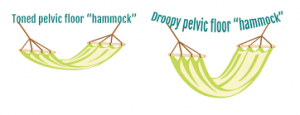

The pelvic floor is made up of a layer of muscles spanning the bottom of the pelvis that support our internal pelvic organs (bladder and bowel in males [1] and bladder, bowel and uterus/womb in women). These muscles run like a hammock front to back from the pubic bone to the tailbone and side-to-side from one sitting bone to the other [2].

These muscles are similar to a trampoline, as they have the ability to move up and down. This occurs during breathing as when we inhale theme shaped diaphragm pulls down to open our lungs. This pushes down of our internal organs. To avoid squashing these organs our pelvic floor and abdominal muscle relax and create more space for the organs to move down. When we exhale the diaphragm springs back to its normal position and as it does so the abdominals and pelvic floor muscles return to their resting position. A common problem experienced by people is holding their breath during lifting activities or bowel movements, which can lead to pelvic floor dysfunctions by adding excess stress on these muscles.[3]

Our pelvic organs sit on top of this layer of muscle. The muscles also have holes through which the urethra and anus pass through in males and urethra, anus and vagina pass through in females. The muscles are snug against these structures in order to hold the passages closed. Both the anus and urethra have extra circular muscles (called sphincters) that help to keep the passages closed and prevent leakage.[4]

Pelvic floor muscles may be hidden but we do have voluntary control of them and therefore they can be trained like muscles in our arms or legs.

Functions of the Pelvic Floor Muscles:

- Support internal pelvic organs in the correct positions (Bladder, bowel and vagina)

- Allow conscious control of bladder and bowel habits using the sphincter muscles. This allows us to control the release of urine, faeces and gas and to delay emptying until a convenient time. This works as the pelvic floor muscles contract the organs are lifted up and the sphincter tighten around the openings of the urethra and anus.

- Allow the passage of urine and faeces out of the body due to the pelvic floor muscles relaxing and allowing the passages to open.

- Sexual function

- In males the pelvic floor muscles are important in erectile function by increasing rigidity and ejaculation by improving control and coordination between circulation, pelvic floor muscles.[5]

- In females voluntary contraction of the pelvic floor muscles can contribute to sexual sensation

- Additionally in pregnant women the pelvic floor offers support to the foetus during pregnancy and also assists in the childbirth process.

Strong pelvic floor muscles are important when we cough, laugh, sneeze or during lifting activities as there is extra force added to the abdomen and therefore additional pressure down onto the pelvic floor. If these muscles are weak, stretched or not working as they should, pressure may be felt in the pelvic region or some urinary or faecal leaking may occur during these activities.

Signs and Symptoms[edit | edit source]

Men:[edit | edit source]

- Constipation or bowel strains

- Ongoing pain in your pelvic region, genitals or rectum.

- A prolapse – may feel as though there is a bulge/ pressure in the rectum or a feeling of needing to use your bowels without actually needing to go. - Accidentally leaking urine when you exercise, laugh, cough or sneeze.

- Feelings of urgency in needing to the bathroom, or not making it there in time.

- Frequent need to urinate.

- Difficultly emptying your bladder (discontinuous urination – stop and start multiple times) and bowels.

- The feeling of needing to have several bowel movements during a short period of time.

- Accidentally passing wind.

- Pain in your lower back that cannot be explained by other causes.

- Pain in the testicles, penis (referred pain from the pelvic floor) or pelvis during intercourse.

- Erectile dysfunction.

- Painful ejaculation.

For further information on the male pelvic floor go to: [1]

Women:[edit | edit source]

- Pain or numbness during intercourse.

- Ongoing pain in your pelvic region, genitals or rectum.

- A prolapse – may be felt as a bulge in the vagina (feeling or seeing a bulge or lump in or coming out of your vagina) or a feeling of heaviness, discomfort, pulling, dragging or dropping sensation.

- Accidentally leaking urine when you exercise, laugh, cough or sneeze (stress incontinence).

- Feelings of urgency in needing to the bathroom, or not making it there in time.

- Frequent need to urinate.

- Difficultly emptying your bladder (discontinuous urination – stop and start multiple times) and bowels.

- The feeling of needing to have several bowel movements during a short period of time.

- Constipation or bowel strains.

- Accidentally passing wind.

- Pain in your lower back that cannot be explained by other causes.

Helpful websites for further information: [2] [3]

Risk Factors[edit | edit source]

Females

- Age: Females experiencing menopause, are at increased risk for developing pelvic organ prolapse (POP) by 21.1%. [6][7]This is most likely due to hormonal fluctuations which change the functioning of female urogenital structures. It includes weakening of the pelvic floor, as the muscle mass tends to decrease during this life stage. [8]

- Direct injury to levator ani and loss of tone in pelvic muscles: The explanation lies within the compensatory mechanism of musculature whereby, the pelvic structures rely on the connective tissue for support. Over time, this alteration results in weakening of the tissue and occurrence of POP.[9]

- Pregnancy and the nature of childbirth: Overstretching/damaging of the prudanal nerve during vaginal birth, prolonged labour, instrumental delivery, episiotomy (surgical procedure to increase opening in vagina), weight and number of children (parity) have also been known to increase the PFD risk by 4-16%. [6][9][10]

- Genetics and ethnicity: Women who have a positive family history of POP, are more likely to inherit the condition, than women who do not. [10] Additionally, it has been shown that females experiencing urinary incontinence, the connective tissue in the pelvic floor muscles may be genetically weak. [11] [12] Furthermore, Kuncharpu et al.’s (2010) [9]and Vergeldt et al.’s (2015)[6] findings, reveal that those with Hispanic descent had greater risk for POP when compared to their African-American and White counterparts.

- Low socioeconomic status (SES):This factor, especially among racial minorities, may contribute to poorer access to adequate information regarding PFD.[7][9]The lack of resources create a challenge for women, making it difficult to recognize the symptoms and importance of seeking professional support in a timely manner.Hartigan and Smith (2018)[13], presented that women of poorer SES scored lower on the incontinence quiz than their higher SES counterparts. Consequently, there is a strong emphasis on public education at large to reduce the risk of PFD.

- Hysterectomy (surgical removal of uterus): This procedure often damages and weakens the pelvic muscles. Therefore, it is known to increase chances of being more predisposed to POP[7][14]. The risk also increases to 60% for developing urinary incontinence post-hysterectomy among middle-aged women[14].

Males

- Prostate surgery: It appears that scientific literature examining pelvic floor dysfunction (PFD) among males is limited. However, prostate surgery has been identified as a potential risk factor [15][16]. Specific PFDs include urinary incontinence and erectile dysfunction, which are quite common post-operatively (up to 89% men suffer from these conditions)[17]. Individuals who undergo this procedure, may experience disturbance in pelvic floor muscles (especially urinary sphincters) and altered nerve supply to the area. In prostatectomy, the prostate (partially regulating continence) is removed, increasing probability for incontinence. The urinary sphincter nerves may occasionally be damaged during surgery due to their proximity to the prostate. As a result, the patients might later experience poor bladder control[18]. Cavernous nerves responsible for erectile function, may also be disrupted[19].

Both genders

- Previous trauma to pelvic region (e.g. fall or pelvic radiotherapy): This is particularly common in less physically active men who underwent pelvic radiotherapy for prostate cancer. The side effects of the treatment, including decreased tone of pelvic floor muscles, are more prominent in this group of patients. As a result of the pelvic muscles weakening, men are more susceptible to experience erectile impairment and urinary incontinence symptoms [20]. In women, pelvic radiation, as suggested by Walters (2017)[21] has created an additional risk factor for urinary incontinence and for developing PFD symptoms. In order to assure quality of life and avoid many discomforts, men and women should require further screening to receive the optimal medical treatment.

- Increased abdominal pressure: Chronic coughing (symptom of chronic lung disease, smoking, hay fever) and frequent sneezing, have been shown to contribute to POP in women[9]. It has been related to overuse of pelvic floor muscles and ligaments supporting the pelvic organs that occurs as the pressure increases within the abdomen.This weakens the anatomical structures and leads to POP[22]. For men, it usually presents as urinary incontinence. The frequent increase in intra-abdominal pressure can lead to the opening of the sphincter, despite the absence of bladder contraction[23].

- Constipation/heavy lifting: Constipation is caused by the altered mechanics (incoordination) of the pelvic floor muscles and increase in intra-abdominal pressure during attempted evacuation. These persistent conditions can lead to nerve damage and appearance of PFD symptoms, such as fecal incontinence[24]. Occupations that require frequent heavy lifting, to add pressure to the bladder and influence urinary incontinence in both genders[25]. However, women who perform prolonged heavy lifting, are 9.6 times more at risk of developing POP[12].

- Prolonged vigorous physical exertion: Elite athletes, engaging in high impact sports (e.g. trampolining, running, gymnastics) compared to low impact sports (e.g. golf), have been shown to experience increase abdominal pressure, which over time often leads to urinary incontinence[11][12][26].

- Increased BMI (above 25)/Obesity: Being overweight as measured by BMI (general indication of body fat), was strongly associated with urinary incontinence symptoms in both genders as was true for POP in women, compared to those with normal BMI values (18.5-24.9) [6][11][20].

- History of back pain: has been noted to be closely related to pelvic floor muscle dysfunction. This is because the pelvic muscles have a role of providing stability for the lower back and bladder control continence. As a result, the discomfort experienced may cause individuals to avoid movement including the use of pelvic floor muscles. These muscles then become weak, unable to support the pelvic floor organs and alter urinary function[27].

Collectively, there are many modifiable and non-modifiable risks for PFD in both genders. Being able to recognize the predispositions, especially those related to lifestyle, can aid in incorporating preventative measures in a timely manner. This also includes seeking the appropriate professional support. The specialists can provide relevant and evidence-based information regarding monitoring, assessment, and intervention available to the public.

Common misconceptions[edit | edit source]

It’s my fault isn’t it? (Smith et al. 2007)

- Woman normalize symptoms – feel that it is part of being a woman and getting older especially after childbirth (mason et al 2001)

- Lack of self control- woman feel is it their own fault for not being able to control bladder

- Woman experiencing POP and associated symptoms such as incontinence feel “deserving”, due to lack of consistency or failure to complete PFMT post childbirth. Woman, blame themselves for having these symptoms.

- Lack of priority given to PFMT post childbirth due to occupation with new baby , lack of perineal sensitivity post delivery have left PFMT low on the priority list. Woman experience self blame for allowing his to occur

- Shame associated with incontinence issues - woman are less willing to seek help from health care professionals as they feel they will be judged reprimanded or blamed for lack of consistency in PFMT

- Lack of understanding – woman have revealed that lack of understanding about PFMT , such as how to actually do a PFM contraction has prevented them from PFMT effectively . Difficulty discussing this issue with healthcare professionals due to the sensitive nature of area.

The silent private exercise (Neels et al. 2017)

- The internal unseen nature of the PFM has led to difficulty for many woman understanding how to train the PFM

- The mysterious nature of the PFMT seems in part due to the difficulty of finding appropriate yet explicit language to explain PFM exercises

- Exercise using muscles that cannot be seen and are located in a private area of the body and are associated with private function not easily discussed

- Study conducted to evaluate health care professionals skills in explaining the PFM contraction- patient described explanation as “sketchy “

- Woman feel silly as they may struggle to grasp technique

- ERRORS – common errors made in an attempt to contract pelvic floor muscles .COMMOV- contraction of other muscles ( using rectus abdominus, glutes and adductors ) MOV- pelvic tilts , breath holding and straining performed in addition to or instead of an actual pelvic floor muscle contraction

- 57% of woman show Commov when assessing technique.

Will pelvic floor muscle training work? (Neels et al. 2018)

- Lack of understanding – Lack of clarity, as to why PFM should be exercised . Woman are unsure as to why these exercises need to be done. Due to the lack of understanding , woman are unable to make informed decision to partake in PFMT

- Waste of time- Woman may find it difficult to continue with PFMT in the absence of noticeable benefit. No immediate effect from training leads woman to feel as though there is no return for their efforts and that PFMT is waste of time

- The nature of PFMT – woman have described PFM exercises as tedious, a daily battle, a nuisance and boring

- Timing? This study conducted found that woman feel the PFMT is difficult to factor into their daily schedule. Due to the personal nature of the exercise need to be done alone and in a quiet place for concentration also many feel embarrassed to do exercises around others

Prolapse and incontinence, it’s a female problem right?(Hirschhorn et al. 2013)

- Study investigated male perceptions of incontinence and pelvic floor muscle training – 66% of men were unaware that males were required to do PFMT

- Widely perceived as a female issue

- Stigma and embarrassment – leads to under reporting of symptoms within the male population

- Lack of research regarding male experiences in PFMT , body of research lies within the female population

Add your content to this page here!

Treatment [edit | edit source]

Pelvic floor dysfunction is a very treatable condition. Treatments will vary according to the nature of the condition or reason behind the PFD. Your appropriate licensed health care practitioner will help you decide which one is best for you:

Conservative:[edit | edit source]

Many strategies exist to treat PFD conservatively and should generally be considered as the first-line option prior to more aggressive procedures such as surgery.

--> PFMT is a very important aspect of improving PFD and is valuable to both men and women. PFMT aims to increase the strength, endurance and co-ordination of the muscles, which improves their overall function. Weak or damaged PF muscles can’t do their job properly and this can contribute to many problems such as incontinence and organ prolapse. A strong pelvic floor will help to prevent incontinence, provide support to pelvic organs and even improve your sex life.

There are many different methods to perform PFMT, a physiotherapist or GP that specializes in pelvic health is best suited to educate you in doing these essential exercises. These specialists may use

Female: http://www.baus.org.uk/_userfiles/pages/files/Patients/Leaflets/Pelvic%20floor%20XS%20female.pdf

Male: http://www.baus.org.uk/_userfiles/pages/files/Patients/Leaflets/Pelvic%20floor%20XS%20male.pdf

--> Lifestyle changes may be suggested by the GP to help improve certain contributing factors.

For example, quitting smoking, increasing your physical activity and improving your diet to achieve a healthier weight are all great strategies to improve your symptoms/condition and overall QoL. One may also try to reduce caffeine and other irritants of the bladder (Coffee, tea, cola, alcohol etc.), while also trying to get enough water intake throughout the day. Certain strategies may be used in vulnerable situations as well. For example, tightening up your PF muscles prior to lifting heavy loads, and when possible, sharing the load with another person to lighten it. This will help to prevent any unwanted leakage or damage.

Pharmacological:[edit | edit source]

Various drugs can be prescribed if indicated based on the underlying reason for PFD and your GP will decide with you if these are necessary. Drug therapy is particularly common for urinary incontinence and depending on the type of incontinence you’re experiencing; different medications are available. For example, if you have a stress incontinence, there are drugs to that help reduce leakage and hormone replacement therapies for post-menopausal women. If you have an over-active bladder or urge incontinence, there are medications to help relax the bladder and reduce the frequency of urination.

Pharmacological treatment is even more effective when used in combination with other strategies like PFMT and lifestyle changes.

For more information, please see NHS website: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/urinary-incontinence/treatment/

Surgical:[edit | edit source]

In some cases, when other strategies have been unsuccessful in achieving your treatment goals, surgery may be a treatment option for you. Depending on your specific condition, various procedures exist to address the problem.

For example, urge and stress incontinence have multiple types of procedures to alter the pelvic structures or insert supports such as mesh slings, both in the goal of improving functions.

Slightly less invasive options are also available, such as injections of Botox for urge incontinence or bulking agents to help reduce stress incontinence.

For more information on bladder procedures, please visit: https://www.baus.org.uk/patients/information_leaflets/category/3/bladder_procedures

For more information on urinary incontinence procedures, please visit: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/urinary-incontinence/surgery/

References:

AYELEKE, R., HAY-SMITH, E. & OMAR, M., 2015. Pelvic floor muscle training added to another active treatment versus the same active treatment alone for urinary incontinence in women. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews.

CLEVELAND CLINIC., 2018. Pelvic floor dysfunction. [online]. [viewed March 10, 2018]. Available from: https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/14459-pelvic-floor-dysfunction/management-and-treatment

NHS., 2018. Urinary Incontinence. [online]. [viewed March 10, 2018]. Available from: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/urinary-incontinence

PHYSIOTHERAPY NEW ZEALAND., 2018. How Physio can help: Pelvic Floor Disorders. [online]. [viewed March 10, 2018]. Available from: http://physiotherapy.org.nz/your-health/how-physio-can-help/pelvic-floor-disorders

ROBERT, M. & ROSS, S., 2006. Conservative management of urinary incontinence. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada. Vol. 28 (12), pp. 1113-1118.

Pelvic floor exercises for beginners:[4]

Pelvic floor exercises for men: [5]

Progressive pelvic floor exercises: Episode 1: [6] Episode 2:[7] Episode 3: [8] Episode 4: [9] Episode 5: [10]

References[edit | edit source]

see adding references tutorial.

- ↑ https://www.continence.org.au/pages/pelvic-floor-men.html

- ↑ http://www.pelvicfloorfirst.org.au/pages/the-pelvic-floor.html

- ↑ https://www.pelvicpainrehab.com/low-tone-pelvic-floor-dysfunction/4587/pelvic-floor-movement/

- ↑ http://pogp.csp.org.uk/publications/pelvic-floor-muscle-exercises-men

- ↑ https://prostate.net/articles/erectile-dysfunction-pelvic-floor-connection

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 VERGELDT, T.F., WEEMHOFF, M., INTHOUT, J. and KLUVIERS, K.B., 2015. Risk factors for pelvic organ prolapse and its recurrence: a systematic review. International urogynecology journal. November, vol.26, no.11, pp.1559-1573.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 WU, J.M., VAUGHN, C.P., GOODE, P.S., REDDEN, D.T., BURGIO, K.L., RICHTER, H.E. and MARKLAND, A.D., 2014. Prevalence and trends of symptomatic pelvic floor disorders in US women. Obstetrics and gynecology, January, vol. 123, no.1, pp.141-148.

- ↑ FROTA, I.P.R., ROCHA, A.B.O., NETO, J.A.V., VASCONCELOS, C.T.M., DE MAGALHAES, T.F., KARBAGE, S.A.L., AUGUSTO, K.L., NASCIMENTO, S.L.D., HADDAD, J.M. and BEZERRA, L.R.P.S., 2018. Pelvic floor muscle function and quality of life in postmenopausal women with and without pelvic floor dysfunction. Acta obstetricia et gynecologica Scandinavica.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 KUNCHARAPU, I., MAJERONI, B.A. and JOHNSON, D.W., 2010. Pelvic organ prolapse. Am Fam Physician. May,vol.81, no.9, pp.1111-1117.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 LINCE, S.L., van KEMPEN, L.C., VIERHOUT, M.E. and KLUVIERS, K.B., 2012. A systematic review of clinical studies on hereditary factors in pelvic organ prolapse. International urogynecology journal. October, vol.23, no.10, pp.1327-1336.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 BO, K., 2012. Urinary incontinence, pelvic floor dysfunction, exercise and sport. Sports Medicine. June,vol.34, no.7, pp.451-464.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 NYGAARD, I.E. and SHAW, J.M., 2016. Physical activity and the pelvic floor. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. February, vol. 214, no.2, pp.164-171.

- ↑ HARTIGAN, S.M. and SMITH, A.L., 2018. Disparities in Female Pelvic Floor Disorders. Current urology reports. February, vol.19, no.2, p.16-22.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 HUMALAJARVI, N., AUKEE P., KAIRALUOMA, M.V., STACH-LEMPINEN, B., SINTONEN, H., VALPAS, A. and HEINONEN, P.K., 2014. Quality of life and pelvic floor dysfunction symptoms after hysterectomy with or without pelvic organ prolapse. European Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. November, vol.182, no. 1, pp.16-21.

- ↑ NHS TRUST., 2014. National Health Service [online]. [viewed 19th March 2018]. Available from: http://www.ouh.nhs.uk/patient-guide/leaflets/files/11124Ppelvic.pdf

- ↑ CSP., 2014. Chartered Society of Physiotherapy [online]. [viewed 19 March 2018]. Available from: www.csp.org.uk/sites/files/csp/secure/pogp-pelvicfloor-male.pdf

- ↑ DOREY,G., 2013. Pelvic floor exercises after radical prostatectomy. British Journal of Nursing.October,vol.14, no.5, pp.457-464.

- ↑ HOYLAND, K., VASDEV, N., ABROF, A. and BOUSTEAD, G., 2014. Post-radical prostatectomy incontinence: etiology and prevention. Reviews in urology. October, vol.16, no.4, p.181-188.

- ↑ GLINA, S., 2011. Erectile dysfunction after radical prostatectomy. Drugs & aging. April, vol.28, no.4, pp.257-266

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 THOMAS, R.J., HOLM, M., WILLIAMS, M., BOWMAN, E., BELLAMY, P., ANDREYEV, J. and MAHER, J., 2013. Lifestyle factors correlate with the risk of late pelvic symptoms after prostatic radiotherapy. Clinical Oncology. April, vol. 25, no.4, pp.246-251.

- ↑ WALTERS, M.D., 2017. Pelvic floor disorders in women: an overview. Revista de Medicina de la Universidad de Navarra. October, vol. 48, no. 4, pp.9-18.

- ↑ CHOI, K.H. and HONG, J.Y., 2014. Management of pelvic organ prolapse. Korean journal of urology. November, vol.55, no.11, pp.693-702.

- ↑ KHANDELWAL, C. and KISTLER, C., 2013. Diagnosis of urinary incontinence. Am Fam Physician. April, vol. 87, no.8, pp.543-550.

- ↑ JAMSHED, N., LEE, Z.E. and OLDEN, K.W., 2011. Diagnostic approach to chronic constipation in adults. American family physician. August, vol. 84, no.3, p.299-306.

- ↑ NASER, S.S.A. and SHAATH, M.Z., 2016. Expert system urination problems diagnosis. World Wide Journal of Multidisciplinary Research and Development, vol,2, no.5, pp.9-19.

- ↑ CONTINENCE FOUNDATION AUSTRALIA 2016. [online] [viewed 17 March 2018]. Available from: http://www.pelvicfloorfirst.org.au/pages/are-you-at-risk.html.

- ↑ ARAB, A.M., BEHBAHANI, R.B., LORESTANI, L. and AZARI, A., 2010. Assessment of pelvic floor muscle function in women with and without low back pain using transabdominal ultrasound. Manual therapy. June, vol.15, no.3, pp.235-239.

6.HAY-SMITH, E., RYAN, K. and DEAN, S., 2007. The silent, private exercise: experiences of pelvic floor muscle training in a sample of women with stress urinary incontinence. Physiotherapy. vol. 93, no. 1, pp. 53-61.

7.HIRSCHHORN, A.D., KOLT, G.S. and BROOKS, A.J., 2013. Barriers and enablers to the provision and receipt of preoperative pelvic floor muscle training for men having radical prostatectomy: a qualitative study. BMC Health Services Research. vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 305.

8.MASON, L., GLENN, S., WALTON, I. and HUGHES, C., 2001. The instruction in pelvic floor exercises provided to women during pregnancy or following delivery. Midwifery. 2001, vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 55-64.

9.NEELS, H., DE WACHTER, S., WYNDAELE, J., VAN AGGELPOEL, T. and VERMANDEL, A., 2018. Common errors made in attempt to contract the pelvic floor muscles in women early after delivery: A prospective observational study. European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Biology. 01, vol. 220, pp. 113-117.