Overview of Cervical Spine Assessment: Difference between revisions

m (change outcome measures to self-assessment questionnaires) |

(Canadian C-Spine Rule) |

||

| Line 129: | Line 129: | ||

* Pre-manipulative position test | * Pre-manipulative position test | ||

==== Canadian C-Spine | ==== Canadian C-Spine Rule ==== | ||

The [[Canadian C-Spine Rule]] is a decision-making tool used to determine when radiography should be utilised in patients following trauma. The tool has a negative likelihood ratio of zero which means that if the test indicates that there is no need for radiographic investigation, then there is no need for an x-ray.<ref>Michaleff ZA, Maher CG, Verhagen AP, Rebbeck T, Lin C-WC. Accuracy of the Canadian C-spine rule and nexus to screen for clinically important cervical spine injury in patients following Blunt Trauma: A systematic review. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2012;184(16). </ref><ref name=":3" /> | The [[Canadian C-Spine Rule]] is a decision-making tool used to determine when radiography should be utilised in patients following trauma. The tool has a negative likelihood ratio of zero which means that if the test indicates that there is no need for radiographic investigation, then there is no need for an x-ray.<ref>Michaleff ZA, Maher CG, Verhagen AP, Rebbeck T, Lin C-WC. Accuracy of the Canadian C-spine rule and nexus to screen for clinically important cervical spine injury in patients following Blunt Trauma: A systematic review. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2012;184(16). </ref><ref name=":3" /> | ||

Revision as of 09:27, 19 December 2023

Top Contributors - Jacquie Kieck, Jess Bell and Kim Jackson

Introduction[edit | edit source]

A thorough assessment is vital for the effective management of any condition. The cervical spine is no different. This page includes a step-by-step overview of the vital elements of a thorough assessment of the cervical spine. The assessment should broadly consist of a subjective assessment (history taking) and an objective assessment (observation and tests). A thorough assessment allows the clinician to classify the client's presentation. A classification system is discussed to guide the clinician in the successful management of the client's presentation.

Subjective Assessment[edit | edit source]

History[edit | edit source]

In this page, the mnemonic L-M-N-O-P-Q-R-S-T is used to cover all the aspects of the history taking in the subjective assessment.

L: Location of symptoms and level of functional impairment

This table gives a summary of the likely source of symptoms based on the area of symptoms.

| Area of Symptoms | Possible Source of Symptoms |

|---|---|

| Head/occipital region | Upper cervical spine |

| Localised pain without radiation/referral |

|

| Radiating pain | Nerve root irritation |

M: Medical factors (medications) and mechanism of injury

In the assessment, be specific in finding out when and how the injury occurred, what forces were applied, and the position of the head at the time of the trauma. Also, ask about the neurological symptoms associated with the trauma. Red flags related to the mechanism of injury would be the sudden onset of severe pain in the absence of an incident or accident.

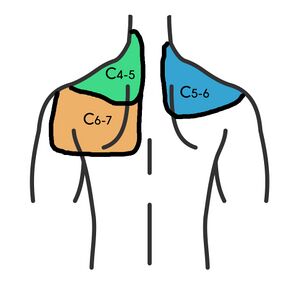

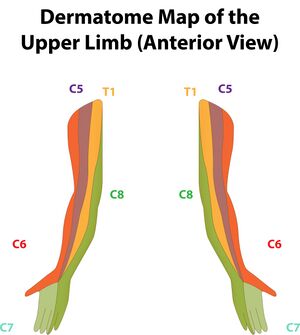

N: Neurological examination

A neurological examination is performed to establish neurologic function and can be used in the hyposthesis of forming a diagnosis.[2] During the neurologic examination it is useful to establish if there are symptoms of numbness, tingling, burning or electrifying symptoms. Be specific about the location of these symptoms i.e. is the distribution of these symptoms dermatomal? The clinician should also note if the symptoms are constant or intermittent and if they are associated with the position of the head.

O: Occupation including limitations

P: Palliating and provocating symptoms

Establish what increases and decreases the symptoms. Also, note how long it takes the symptoms to calm down once aggravated. A red flag would be constant/unrelenting pain independent of position or activity.

Q: Quality of symptoms/pain

This would cover the description of the symptoms for example, sharp, dull, stabbing, aching or electric/shock-like symptoms.

R: Radiation of symptoms

Be specific about where the symptoms radiate, how long the radiating symptoms last, and whether they are constant or position/activity related. A red flag would be if the radiating symptoms cover multiple dermatomes.

S: Severity of symptoms

Note how the symptoms impact function and activity.

T: Timing of symptoms

Ask about the sequence and progression of symptoms. Red flags would be if the pain is interrupting sleep or constant/unrelenting pain.

Be sure to include questions about age, history of neck pain, constitutional symptoms, dizziness, drop attacks and vertigo, paraesthesia, numbness, weakness, or stiffness.

Red Flags[edit | edit source]

Red flags are symptoms that suggest the presence serious pathology. International guidelines recommend using red flags to identify serious pathology.[3] Below is a list of red flags to screen for when assessing the cervical spine:

- Severe loss of range of motion (ROM) with sudden onset of symptoms

- Changes in balance/gait

- Hypo/ hyperreflexia

- Constant pain

- Severe radiating pain

- Moderate to severe occipital headache

- Facial pain

- Psychological changes

- Cranial nerve symptoms

- Dizziness

- Horner syndrome

- Hemiparaesthesia

- Bowel and bladder change

- Ataxia

- Nystagmus

- Drop attacks

- Hemifacial parathaesia

- Dysphagia

The History Can Be Suggestive of Certain Conditions[edit | edit source]

History suggesting cervical spondylosis[edit | edit source]

A history suggestive of cervical spondylosis would include a person over the age of 45 years with gradual, slow onset of symptoms (no specific incident). The pain is usually unilateral and radiates in a facet joint referral pattern. Pain usually increases with extension ('closing down' of the joint) and reduces with flexion ('opening' of the joint). The most commonly affected levels of the cervical spine are C5,C6, C7.[4][1]

History suggesting disc involvement[edit | edit source]

A history suggestive of cervical disc involvement would include a person under the age of 60 years, with sudden onset of symptoms (no specific incident). The pain is usually unilateral and radiates in a dermatomal referral pattern. Pain usually increases with flexion. The most commonly affected levels of the cervical spine are C5,C6.[4]

Self-Assessment Questionnaires[edit | edit source]

Useful self-assessment questionnaires in the assessment of the cervical spine:

- Neck Disability Index (NDI)[5][6]

- Patient Specific Functional Scale (PSFS)[6]

- Fear-Avoidance Belief Questionnaire (FABQ)[7]

- Numeric Pain Rating Scale (NPRS)[5][6]

Objective Assessment[edit | edit source]

Observation[edit | edit source]

General observation of posture, including the position of the head, neck, and shoulders should be done. Also, observe for any signs of torticollis.

Instability Testing[edit | edit source]

The Sharp-Purser test is used to test the integrity of the transverse ligament, however, there are concerns about the reliability, validity, and safety of this test.[8]

Vertebral Artery Testing[edit | edit source]

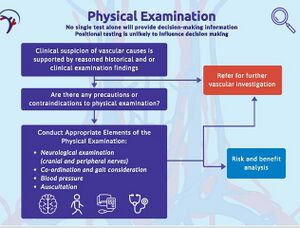

Symptoms of vertebral insufficiency include dizziness/vertigo, nausea/vomiting, inability to stand, blurred vision/diplopia, headache, facial parasthaesia/facial palsy/difficulty swallowing.[9]

Following a thorough subjective assessment of the cervical spine, careful planning of the physical examination should be done, together with consideration of any precautions and contraindications related to further examination of vertebral insufficiency.

In addition, the clinician should also reflect on their ability to perform certain tests and seek additional training if needed.[9]

The following tests can be included for the assessment of vertebral artery insufficiency:[4]

- Hautant test

- Cervical quadrant test

- Pre-manipulative position test

Canadian C-Spine Rule[edit | edit source]

The Canadian C-Spine Rule is a decision-making tool used to determine when radiography should be utilised in patients following trauma. The tool has a negative likelihood ratio of zero which means that if the test indicates that there is no need for radiographic investigation, then there is no need for an x-ray.[10][4]

Functional Screening[edit | edit source]

Typically, a functional screen would include a chin tuck action, cervical flexion, extension and rotation, as well as shoulder movements.

Palpation[edit | edit source]

Palpation would include palpation of the relevant musculature of the cervical spine, as well as the spinous processes and facet joints.

Range of Motion[edit | edit source]

When assessing the range of motion of the cervical spine take note of symptoms associated with the movements. Generally, over-pressure is not applied when testing the range of motion of the cervical spine as the weight of the head is sufficient for testing.

Muscle Testing[edit | edit source]

A lack of endurance and ability to hold the neck in position due to weakness of the cervical deep neck flexors is related to neck pain.[11] To assess the capability of the deep neck flexors, The Deep Cervical Flexion Test or Cranial Cervical Flexion Test, as well as neck flexor endurance testing can be performed.

Neurological Testing[edit | edit source]

A neurological screen will include testing of reflexes, spinal cord reflexes, dermatomal and myotomal testing. Also, include a cranial nerve screen and upper limb tension tests.

Joint Mobility Testing[edit | edit source]

Passive physiological intervertebral mobility testing, passive intervertebral testing and intervertebral glides are included in the assessment of joint mobility.

Special Tests[edit | edit source]

The suggested special tests included in the assessment of the cervical spine are:

- Cervical Compression Test

- Pain with this test may be indicative of an intervertebral disc issue, vertebral fracture, or nerve root irritation (if there are radiating symptoms

- The test can be modified to stress certain tissues i.e. applying compression with the neck in a more flexed position will stress the disc and vertebral body, while applying compression with the neck in a more extended position will stress the facet joint and the nerve as it exits the formina

- Cervical Distraction Test

- Decreased pain with distraction may be indicative of disc pathology, nerve root compression or facet joint pathology

- Spurling's A Test[12][13]

- The Spurling's test has a good specificity, but a low sensitivity and is most useful when used in conjunction with other tests.

- Test Item Cluster

- A test item cluster of Spurling's Test, Upper Limb Tension Test 1, Cervical Distraction Test and Cervical Rotation Test has demonstrated that, when combined, they have high diagnostic accuracy compared to EMG studies. [14]

- Shoulder Abduction Test or Bakody Sign

- For this test, the client is asked to place the affected extremity on their head. If symptoms reduce, the test is positive.

Classification of Cervical Spine Pain[edit | edit source]

A classification system identifies groups with common characteristics as indicated by clinical examination. This determines the intervention(s) which produce optimal clinical outcomes within certain groups. [4] Subjects matched to intervention had greater disability reduction than those in unmatched intervention. [15]

| Classification | Key Feature | Examination Findings | Intervention Focus |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neck Pain with Mobility Deficits | Mobility |

|

|

| Neck Pain with Radiating Pain | Centralisation |

|

|

| Neck Pain with Movement Coordination Impairments | Conditioning Exercise |

|

|

| Neck Pain | Pain |

|

|

| Neck Pain with Headache | Headache |

|

|

Resources[edit | edit source]

- International Framework for Examination of the Cervical Region for potential of vascular pathologies of the neck prior to Orthopaedic Manual Therapy (OMT) Intervention: International IFOMPT Cervical [9]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Hurley RW, Adams MCB, Barad M, Bhaskar A, Bhatia A, Chadwick A, et al. Consensus practice guidelines on interventions for cervical spine (facet) joint pain from a multispecialty international working group. Regional Anesthesia & Pain Medicine [Internet]. 2021 Nov 7 [cited 2022 Jan 20];47(1).

- ↑ Shahrokhi M, Asuncion RM. Neurologic exam. InStatPearls [Internet] 2022 Jan 20. StatPearls Publishing.

- ↑ Childs, J.D., Cleland, J.A., Elliott, J.M., Teyhen, D.S., Wainner, R.S., Whitman, J.M., Sopky, B.J., Godges, J.J., Flynn, T.W., Delitto, A. and Dyriw, G.M. Neck pain: clinical practice guidelines linked to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health from the Orthopaedic Section of the American Physical Therapy Association. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy. 2008; 38(9):A1-A34.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 Cunningham, S. An Overview of Cervical Spine Assessment. Course. Plus. 2023.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Cleland JA, Childs JD, Whitman JM. Psychometric Properties of the neck disability index and numeric pain rating scale in patients with mechanical neck pain. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2008;89(1):69–74.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Basson CA, Olivier B, Rushton A. Neck pain in South Africa: An overview of the prevalence, assessment and management for the Contemporary Clinician. South African Journal of Physiotherapy. 2019;75(1).

- ↑ Waddell G, Newton M, Henderson I, Somerville D, Main CJ. A fear-avoidance beliefs questionnaire (FABQ) and the role of fear-avoidance beliefs in chronic low back pain and disability. Pain. 1993;52(2):157–68.

- ↑ Mansfield CJ, Domnisch C, Iglar L, Boucher L, Onate J, Briggs M. Systematic review of the diagnostic accuracy, reliability, and safety of the sharp-purser test. Journal of Manual & Manipulative Therapy. 2019;28(2):72–81.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Rushton A, Carlesso LC, Flynn T, Hing WA, Rubinstein SM, Vogel S, et al. International Framework for examination of the cervical region for potential of vascular pathologies of the neck prior to musculoskeletal intervention: International IFOMPT cervical framework. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy. 2023;53(1):7–22.

- ↑ Michaleff ZA, Maher CG, Verhagen AP, Rebbeck T, Lin C-WC. Accuracy of the Canadian C-spine rule and nexus to screen for clinically important cervical spine injury in patients following Blunt Trauma: A systematic review. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2012;184(16).

- ↑ Kamayoga ID, Adyasputri AA, Putra IP, Widnyana M, Utama AA. The efficacy of deep cervical flexor training with feedback reducing pain and disability in individuals with work-related Neck Pain. Physical Therapy Journal of Indonesia. 2021;2(2):50–3.

- ↑ Rubinstein SM, Pool JJ, van Tulder MW, Riphagen II, de Vet HC. A systematic review of the diagnostic accuracy of provocative tests of the neck for diagnosing cervical radiculopathy. Eur Spine J. 2007; 16: 307-319.

- ↑ Kang KC, Lee HS, Lee JH. Cervical Radiculopathy Focus on Characteristics and Differential Diagnosis. Asian Spine Journal [Internet]. 2020 Dec 1;14(6):921–30. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7788378/

- ↑ Wainner RS, Fritz JM, Irrgang JJ, Boninger ML, Delitto A, Allison S. Reliability and diagnostic accuracy of the clinical examination and patient self-report measures for cervical radiculopathy. Spine 2003; 28(1):52-62

- ↑ Fritz JM, Brennan GP. Preliminary Examination of a Proposed Treatment-Based Classification System for Patients Receiving Physical Therapy Interventions for Neck Pain. Physical Therapy. 2007 May 1;87(5):513–24.